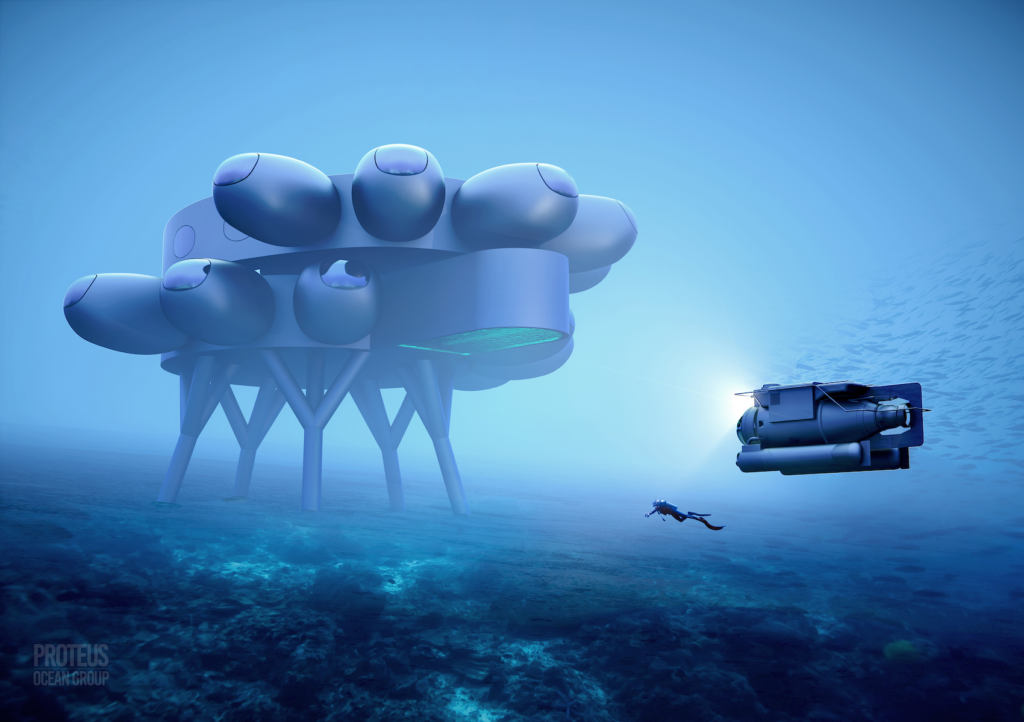

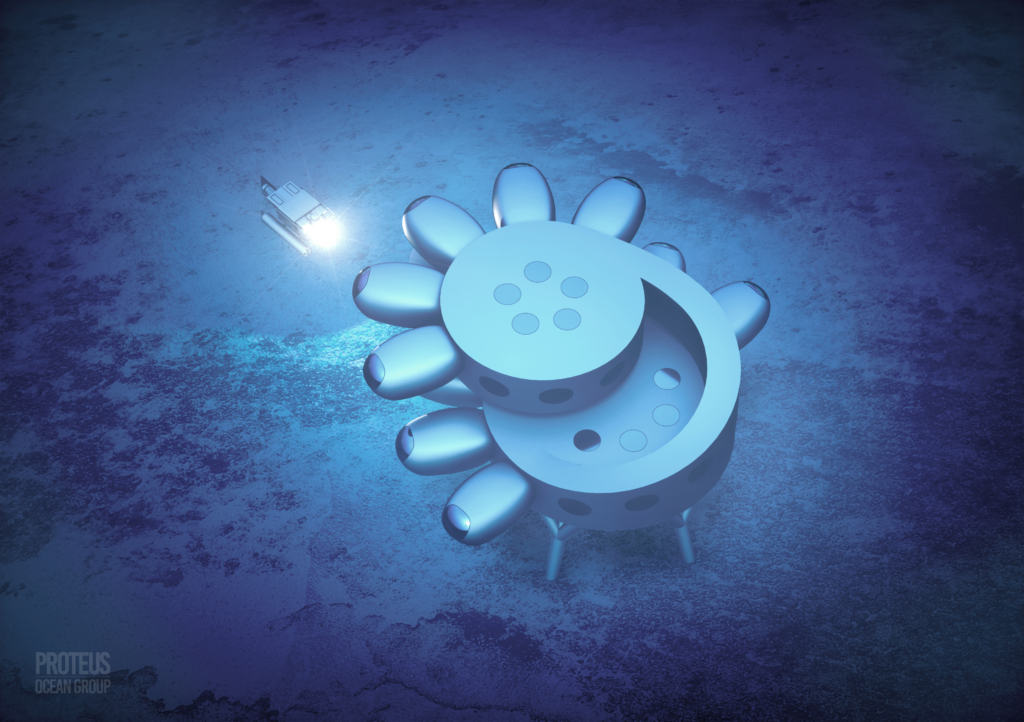

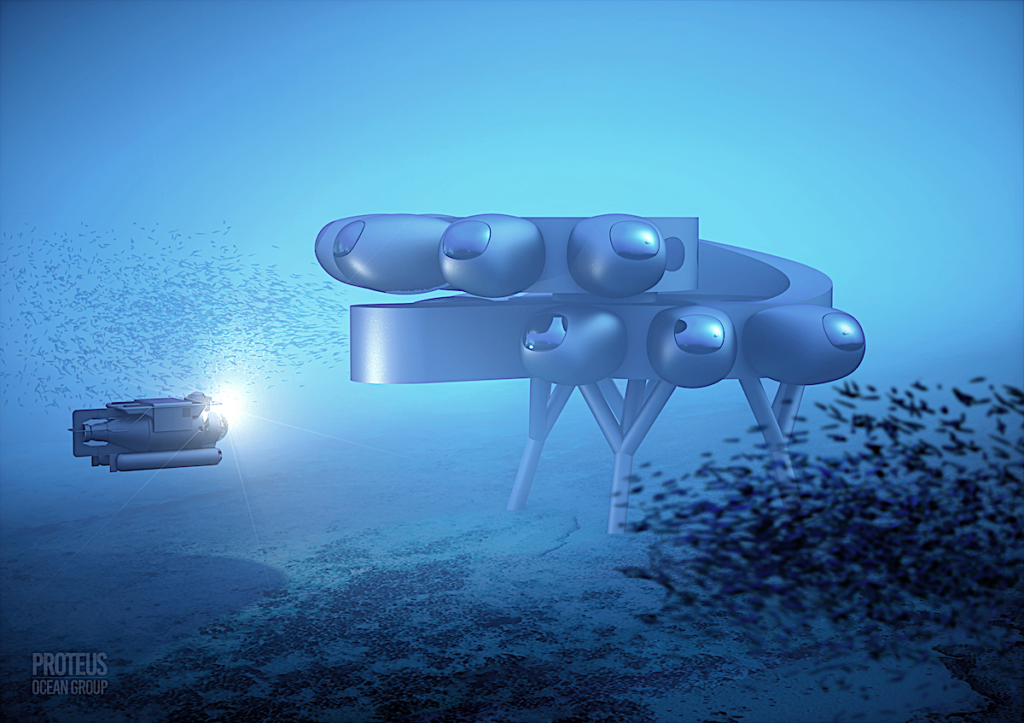

PROTEUS™ — the undersea equivalent of the International Space Station — will speed scientific discovery and may even spur medical breakthroughs.

AN INTERVIEW WITH FABIEN COUSTEAU AND BRIAN HELMUTH

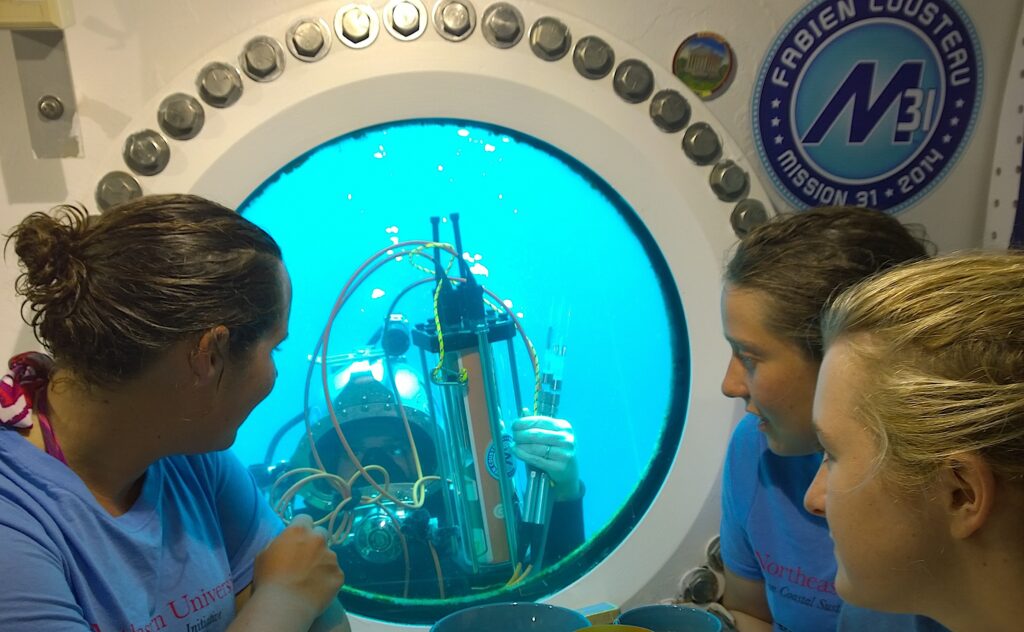

This past June marked the tenth anniversary of Fabien Cousteau’s Mission 31, during which he led a team of aquanauts on an extended research operation on the ocean floor aboard the Aquarius Reef Base off the Florida Keys. Cousteau’s 31 consecutive days aboard Aquarius demonstrated how underwater habitation can speed scientific discovery significantly. He and his team accomplished three years’ worth of research in one month.

Cousteau’s team also broadcasted their activities nonstop, keeping their underwater mission — and ocean intrigue — in the public eye. In this way, Mission 31 also served as a tribute to Cousteau’s grandfather, who raised awareness about marine conservation and research through his own underwater adventures, as well as the popular television series “The Undersea World of Jacques Cousteau.” In the early 1960s, Jacques Cousteau’s team also developed Continental Shelf Station I, II, and III off the coast of France, and the elder Cousteau himself had worked in “Conshelf” II for 30 consecutive days.

As Mission 31 engaged students around the world, it also ignited Fabien Cousteau’s vision for the next generation of an ocean science center — PROTEUS™. This seafloor observatory and research platform will serve scientists, innovators, and others in the search for solutions to critical concerns, such as food sustainability and climate impacts, as well as opening new avenues to medical discoveries and other advances.

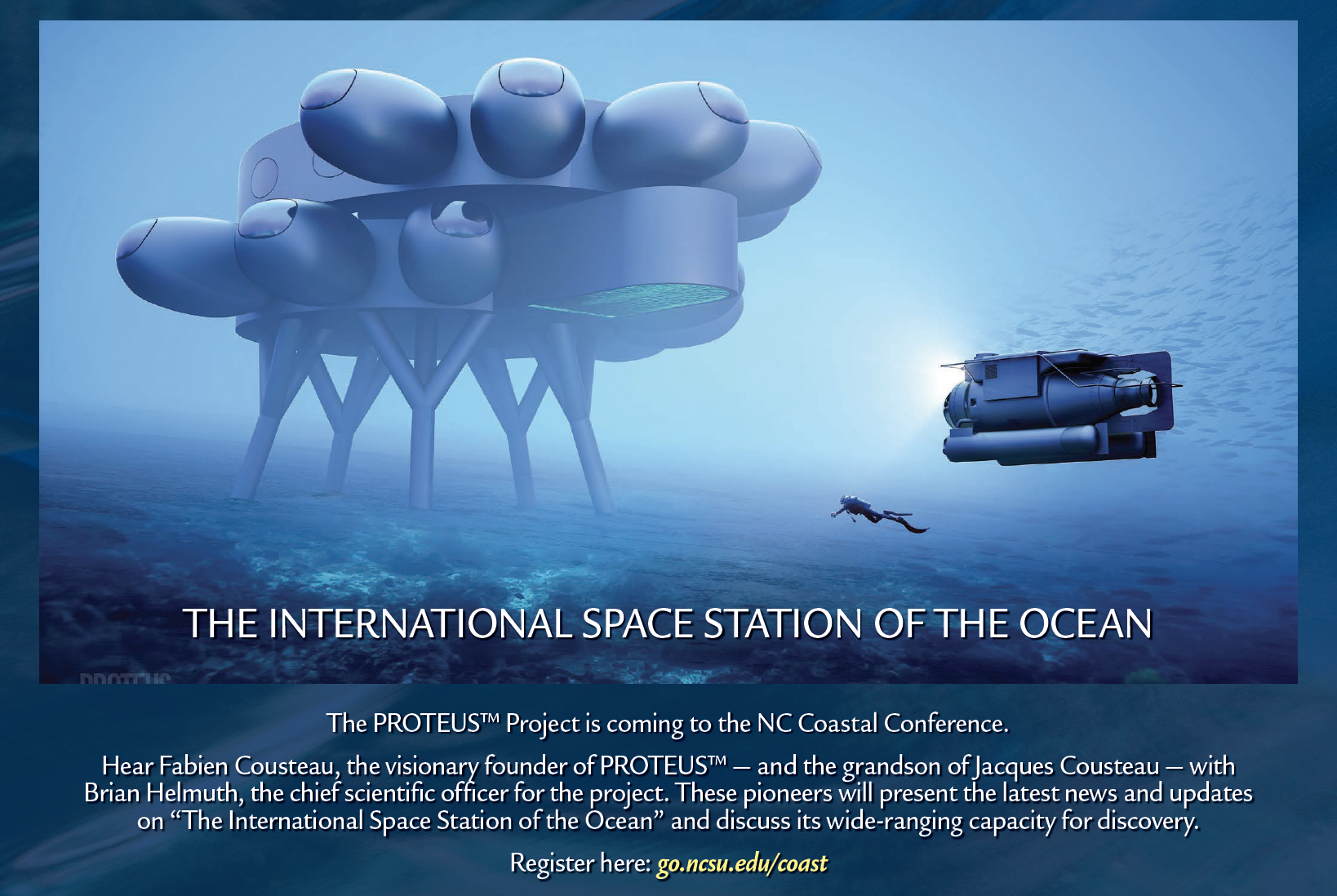

The PROTEUS™ team recently completed mapping the site of the research observatory’s proposed location at a marine park off the coast of Curaçao. Already, PROTEUS™ has captured collective imagination as “The ISS of the Ocean,” and in November, Cousteau and his chief scientific officer, Brian Helmuth, will be panelists for the NC Coastal Conference.

Helmuth, a former member of the National Sea Grant Advisory Board, has served for 25 years at the Marine Science Center at Northeastern University. Cousteau’s adventurous background — as aquanaut, oceanographic explorer, environmental advocate, and founder of both the Fabien Cousteau Ocean Learning Center and the PROTEUS™ Ocean Group — has included an estimated 25,000 hours underwater.

Cousteau and Helmuth talked with Coastwatch three days before the PROTEUS™ team reconvened in Curaçao to plan their next steps.

Fabien, we’ve just marked the tenth anniversary of Mission 31. How did that experience help shape your early thinking about PROTEUS™?

FABIEN COUSTEAU: Mission 31 was a culmination of a lot of questions I’ve had in my head since my first dive, when I was the ripe old age of 4 years old, which can be summarized now into two main issues.

First, why are we not leveraging all the tools at our disposal to explore, to congregate with, to learn from, and to bring back solutions from our life support system — the ocean?

Second, do people still care? Does the general public — as it did in the 60s and 70s — still get just as fascinated and care about ocean mysteries, ocean discoveries, and our ocean connection?

If you look at all the lifeless brown rocks in space, and all the hundreds of billions, if not trillions, of dollars that we’ve spent as a global society in space exploration, it just further highlights why this planet is so unique. Why are we not spending at least as much in ocean exploration?

And why does this kind of tool — an underwater research station or underwater “colony,” if you want to call it that — why has that kind of approach been neglected?

There’s only one habitat that’s publicly accessible, that we know of, that still functions as an underwater research station in the entire world. And that’s Aquarius.

So, I had the wonderful opportunity and privilege to meet some very special people a couple of years prior to Mission 31, including Brian and his intrepid coworker, Dr. Mark Patterson [now at Northeastern University and serving as chief robotics officer for the PROTEUS™ team], who was at the time on a mission with one of our close friends, Dr. Sylvia Earle [Time Magazine’s first “Hero for the Planet” in 1998 and the first woman to serve as chief scientist for NOAA].

And having had the opportunity to go down and visit them for a glorious 47 minutes on Aquarius during their five-day mission, I realized that this was a very special place. This kind of platform is a very unique type of approach.

It started my journey to look at how do we accomplish something with a fairly economically-sized habitat or platform? And how long can we do that for? And what can we learn from it?

Mission 31 ended after 31 days, because it pays homage to my grandfather’s 30 days with Conshelf II, and it also gave us enough time to really see if we could leverage that kind of platform in various ways.

Thanks not only to the team that I led in saturation to become aquanauts, but to the full surface crew from Northeastern University, Florida International University, the U.S. Navy, and others, we were able to accomplish the equivalent of about three years’ worth of research.

And, second, we were able to reach over 100,000 students live.

Now, this is 2014, and this is 9 miles offshore, at the bottom of the sea. For the first time in my life, we were able to have wi-fi and 24/7 live-streaming from an expedition. And so, we had curious people looking in at what these aquanauts were doing at 3 o’clock in the morning.

But, also, we’re able to connect with students from all six continents. That was really neat, you know, students outside the water column asking questions to the aquanauts. We had coms in our helmets, so we were able to do a live stream to a group in China, to a group in South America, and so on.

The enthusiasm — the Aha! moment that you see on their faces — was just proof positive that you can engage the general public in ways that make them understand and appreciate our connection with the ocean.

This is also a very valuable tool to be able to understand more comprehensively about conservation, about the importance of science and math and technology, and engineering, as it pertains to this extreme environment we call the ocean world.

Really, you know, everything including what is a seemingly-trite action of the boom of a Goliath grouper. We had a prototype camera, which at that point could shoot 20,000 frames a second. We can show the boom of that Goliath grouper and that cavitation bubble hotter than the surface of the sun, for a split second. So, people get fascinated.

You’ll see the microcosmic when we’re looking at the biomechanics of the mantis shrimp trying to hunt — with this punch stronger than a .22 caliber bullet. Illustration and storytelling are just as important as the science behind all of this.

And so that’s what not only started our journey toward PROTEUS™ but got me really fascinated with underwater habitats as the missing tool in the toolbox.

The potential of PROTEUS™ for “disruptive scientific breakthroughs” has drawn a lot of attention. Brian, from your perspective as the chief scientific officer, could you tell us about what you see as the project’s capacity for discovery over the next few years?

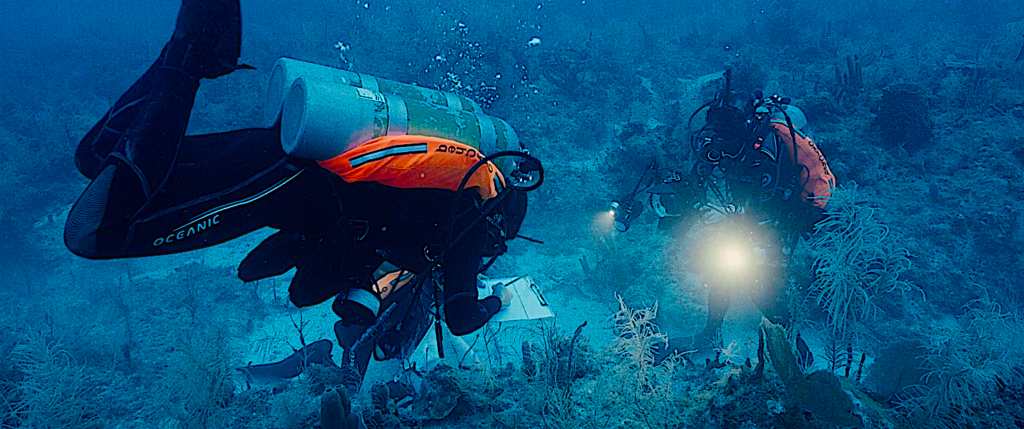

BRIAN HELMUTH: Living underwater and saturation diving is not just an incremental step. It’s a massive step change that provides opportunities. You’re not just conducting science, but understanding the ocean, and I really don’t think there’s any other way to do it.

I’ve been able to do a couple of saturation missions in Aquarius, and you get the “gift of time,” which is what Sylvia Earle calls it, where you have extended bottom time, and have the ability to deploy very sensitive instrumentation, which you can run back to the habitat. So, you can continuously collect data.

You also really have a cognitive shift in how you view your surroundings — Fabien, I don’t know if you felt this — where, after about three days, you become almost actively hostile towards the surface world, and you feel like you’re part of that ocean ecosystem. I mean, we would name the fish. The fish would become comfortable with us. They’d follow us around.

My first mission in St. Croix, we had a pod of dolphins that would wait for us to come out of a habitat. And they would follow us around. I did one mission where a giant moray eel would come over and sit between my legs and watch me do science.

And it provides insights that otherwise are just not possible, certainly not from barreling down there as a surface diver, trying to do everything before you run out of air and run up to the top. But also possibly by not using things like remote or robotic vehicles.

We like to say that no kid ever wants to grow up to be a robot. Robotics and automation are fantastic, but there are things that humans are really good at doing on the fly, as far as decision making, as far as changing the course if things aren’t going the way you’re expecting, that really provides those Aha! moments of science that we all crave and love.

And so, I’m absolutely convinced that living on the seafloor is the most sorely-needed tool right now. Fabien’s grandfather built Conshelf in the 1960s, followed by SEALAB [which the U.S. Navy constructed]. Aquarius is a fantastic platform, but it’s really not all that different from its predecessors.

I mean, it’s a small environment, where you’re living with five of your closest friends, and I can say, after 31 days Fabien looked pretty ragged when he came out of it after a month on the seafloor. I know he didn’t want to come up, but he looked pretty ragged.

What if, instead — and this is what really draws me to Fabien’s vision — we think of this as living on the seafloor as part of the ecosystem in a habitat? You can live comfortably, you can do so sustainably, so that you can really explore the ecosystem as a member of it doing research. I don’t see any other comparable method out there right now.

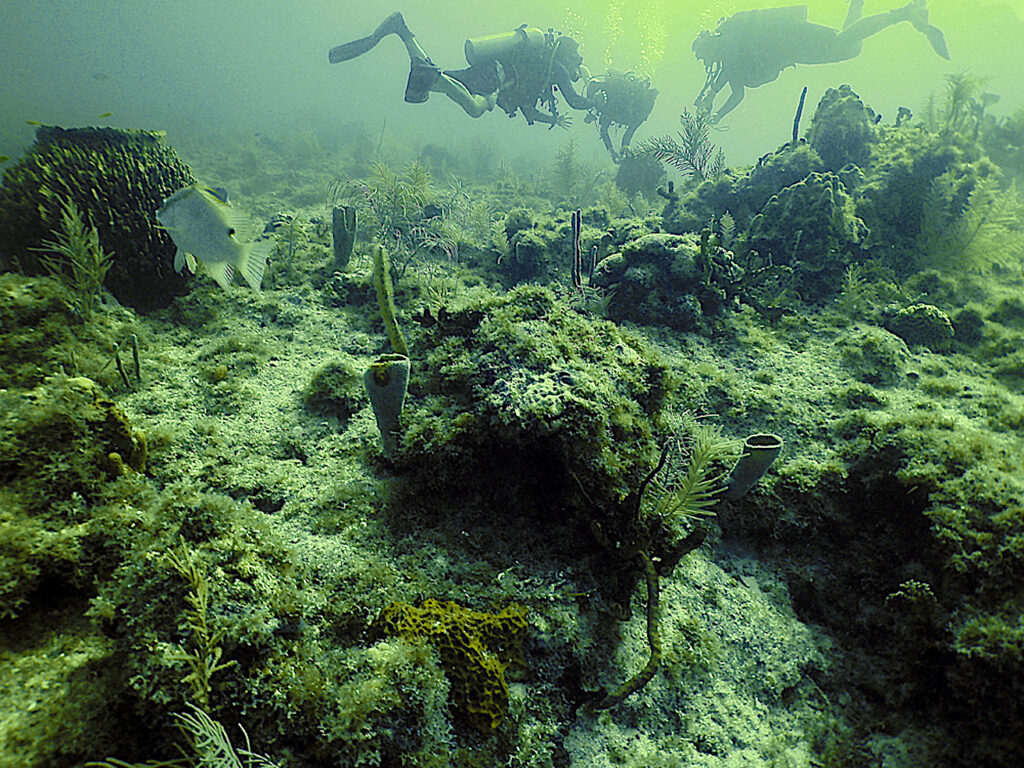

There are so many avenues of exploration. Climate science, for one thing — we talk about climate in terms of global average temperatures, you know, a 1.5° C increase in average surface temperature on the planet. That means nothing to most people. And honestly, it doesn’t mean anything to an animal or plant in the ocean either. They’re not experiencing climate. They’re experiencing weather, driven by climate.

So, when we spend time on the seafloor, we know that those ocean conditions are changing constantly. If you’re living on the seafloor, you are seeing those 24/7 changes. You’re seeing the changeover in the biota as you have the daily migration up from deeper waters. You’re experiencing ocean weather and what that does to the marine life around you.

Now, imagine you’ve got a fully kitted-out laboratory on the station where you could look at gene expression, physiological changes, in real time to match with those weather data that you’re collecting using a sensor network.

There’s also the discovery of natural products. Right now, the cure for cancer is probably in the ocean, but the way we’re collecting samples is we’re going and we’re grabbing them. And bringing them to the surface, and we hope that things don’t explode before we can get a sample out of them.

All the gene expression is changing by the time you get to the surface. Nothing is natural for that organism. The chemicals it’s producing, the genes it’s expressing are totally different than on the bottom. Again, what if we did it on the bottom, in situ, under natural conditions?

We could do that with PROTEUS™, in the lab and outside of the lab, as part of this kind of ecosystem that we’re planning to build. So, I get really excited about this.

Fabien, could you please talk about why education and awareness are as vital to your vision for PROTEUS™ as the science?

FABIEN: It’s been three generations of trying to connect people to the importance, the beauty, the fragility, and the interconnectivity of ocean and human, ocean and all life — our interdependence with regard to that amazing environment.

I feel there’s a combination of challenges that we have emotionally and psychologically with this understanding. Storytelling plays a fundamental role, but by and large there have been a select few people who can “anthropomorphize” the ocean in a way that the average person gets without sacrificing scientific value and accuracy.

The importance of the ocean can’t be overstated. But the way it’s been delivered to the average person who’s not a scientist, who may not even be inclined to go to the ocean for any kind of activities, unfortunately has been mostly about urgency, mostly about science but in a way that’s very dry and very negative.

And when we’re facing some of the fundamental challenges we are now, raising the alarm bells over and over and over again for the last couple of decades, I see a lot of people just kind of disconnect on the emotional level.

Now, the flip side of this is many of us look forward to vacations on the beach somewhere where there’s an ocean nearby.

How does the ocean make you feel when you walk? And the beach, when you’re sitting with a glass of wine watching the sunset over the ocean horizon? How does it make you feel when your children are splashing around in the ocean? Or snorkeling and looking at really crazy, beautiful, unique species that exist nowhere else in the known universe?

How does it feel when you touch an octopus tentacle with the tip of your finger and watch it curiously feeling you out and assessing who and what you are — and watching it puzzle solve during this time, even though it’s a different kind of intelligence?

Those things are economic intangibles that when we talk about the ocean, we need to incorporate into the understanding of why that place is so important.

For so long, for decades, we’ve been using this as a seemingly endless resource and as a garbage can. And now we’re looking at the repercussions. And we’re waking up to a lot of challenges.

In order for us to get the vast majority of the public engaged in solution-building and implementation, we have to be able to let them fall in love with the ocean. My grandfather said very simply, back when I was growing up, that people protect what they love, they love what they understand, and they understand what they’re taught.

The more you get people interested, the more likely that you are to have new recruits for science, for engineering, for technology, for the arts, for all sorts of really fundamental things in our everyday lives. If we can use the ocean as that conduit, then we can also shepherd their appreciation and their protection for our large support system.

Brian, some of your work in the academic sphere has addressed what Fabien has just described — how storytelling and the use of art can infuse conservation efforts. What have you learned about that process that can help bring not only broader awareness but meaningful awareness about ocean ecosystems, climate change, pollution, contaminants, and so on?

BRIAN: I served on the National Sea Grant Advisory Board for eight years, and I’m a huge fan of the Sea Grant model [a collaborative approach of scientists and specialists partnering with coastal communities on research, outreach, and education]. I love the quote from Fabien’s grandfather. I think the way we view it now is: how do you co-develop solutions? How do you find the things that matter to people by working collaboratively with them?

And so, I think one of the big visions we have for this adventure with PROTEUS™ is how to bring the rest of the world along — not as passive observers, but as participants.

So, how do we use things like storytelling and “digital twins” [virtual representations of physical objects or systems]? What we’re trying to do is increase the connectedness that people have to the ocean.

Over my career, I’ve spent a lot of time coming up with, I think, very clever ways of solving ocean problems only to get really frustrated when nobody uses them. Science and technology only get you part of the way. It’s that community engagement. It’s the co-development of solutions. It’s listening to people’s needs as your starting point that makes all the difference in the world.

for training all sorts of different disciplines, including, of course, space exploration and colonization.” Credit: Fabien Cousteau/PROTEUS™ Ocean Group.

PROTEUS™ is not just thinking of the science. It’s thinking how do you couple that with storytelling in a way that makes it collaborative?

For Mission 31, we connected to several museums around the world — the aquanauts on the bottom and the surface team — and were able to have schoolkids ask questions. Now, imagine if we can have them driving submersibles underwater and actually conducting scientific research, by analyzing some of the photos and the videos, having them inform some of the scientific experiments that get done on the seafloor.

That’s the kind of next-gen approach that we want to take, that’s collaborative in nature. And again, I think, it really fits well with that Sea Grant model of looking at people as part of the ocean rather than as something separate.

We’re looking at PROTEUS™ as a convening space across a wide range of organizations and people. We understand the power of working with government agencies, but also with the private sector, also with NGOs.

And I really think part of the power of PROTEUS™ is the ability to bring together the strengths of those different areas. So, how do we look for solutions in ways that look under every rock, and are as inclusive as possible, and do things in a way that hasn’t been done before?

“The ISS of the Ocean” — this characterization of PROTEUS™ as the ocean’s equivalent of an international space station reflects the natural associations people make between sea and space exploration.

FABIEN: We saw this in the 60s and 70s, and now we’re starting to see a resurgence of those comparisons in 2024. The ISS is certainly a major platform and player in the storytelling aspect of space exploration, and so to transpose it into the ocean is just a natural progression of things.

And there’s a reason to call PROTEUS™ the “ISS of the Ocean.” It’s very much as modular and complex, and we are in just as much of an extreme environment as we would be in space. Arguably, it would take just as long to bring back someone who may need some attention at the surface as it would to bring back someone from the ISS.

Those extreme environments have a lot of similarities and analogs. If you are in almost any kind of carrier, there’s no substitute for having live-fire exercises. You know, it’s great to be able to do dry runs in safe environments, but before you send hundreds of millions of dollars and personnel into space, it would be great to be able to make sure that those people and that equipment are ready for any and all types of situations.

And so, as an extreme environment, the ocean is a perfect analog for training all sorts of different disciplines, including, of course, space exploration and colonization.

Except, I will say we have a lot prettier view, along with things to interact with. And we also have a lot of those aliens that they’re still looking for in space.

Related:

The PROTEUS™ Site Mapping video.

Coastwatch on an ocean-born medical safety test: “Blood Draw at the Horseshoe Corral”

- Categories: