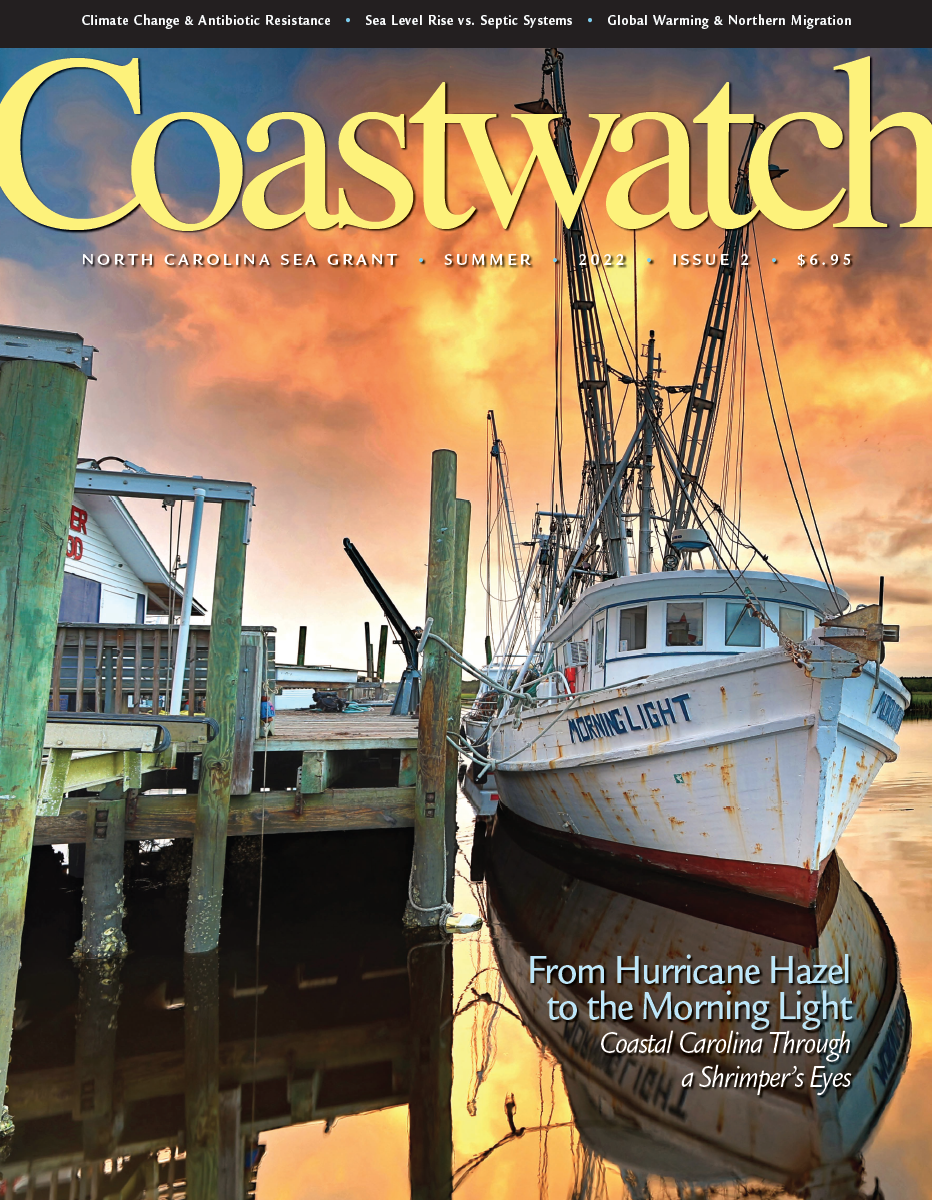

From Hurricane Hazel to the Morning Light

Harry Bryant, a 32-year NC Shrimper, Interviewed by Melody Hunter-Pillion

featuring photographs by Terrah Hewett

Harry Bryant began farming with his father in Supply, North Carolina, before becoming a licensed plumber and then launching a 32-year career as a shrimper. After using scrap metal to build his own 56-foot boat, he would escape waterspouts and a lightning strike, witness the effects of climate change firsthand, and successfully earn a living on the open waters pulling two 60-foot nets. Here, we include excerpts of Melody Hunter-Pillion’s interview with him on his 84th birthday. They opened their talk by discussing the Bryant family’s roots.

Harry Bryant: My ancestors arrived in Brunswick County in 1863 with the man — with the slave owner. And whenever that slavery broke, he had not changed their name, so they remained to be Bryants right on, and they refused. He tried to get them to change their names to Lancaster, because that was a homage to those slaveholders. They refused to change their name, and so we remained to be Bryants right on.

Melody Hunter-Pillion: When emancipation happened and the family became free, do you know what kind of work your family started doing? Was it farming right off?

Harry Bryant: Yes, because they farmed for the Lancaster man. And then, my dad stayed in the farming business the rest of his life.

How long did you farm with your father, and what made you change?

Well, the farming business outgrowed me. You had to have so much more equipment, and we had about 35 acres of not too productive land. And so, we just couldn’t make a living.

See, long as we had tobacco, we could, we could make a living. We go out, and we had an allotment ourself of about three or four acres.

And so, then after a while you had to have a lot equipment, and then finally tobacco just went out of existence, you know, except in Brunswick County. Now, I think there are two tobacco farmers, and they plant 100 acres.

Was your family always in this part of Brunswick County?

Yes. This was some of the slave owner’s land right here where we’re sitting on now. Unless I has to go to a nursing home, I would never sell none of it.

Where would I go without some land? I don’t know where to go. You know?

When your grandfather and dad were adults, having land was, even now, is meaningful, but it was difficult sometimes for African Americans to acquire land.

Well, back in that day, it was very important for them, because that was like you having money in the bank. You know, if you didn’t have no land, you didn’t, you didn’t have no money. But if you had land, you had value.

WATER AND GOLF

Is it harder to keep land now?

Yes. A lot of people sell it because they can’t pay the taxes. You see, we’re getting so many goods and services in the county that the tax value, the tax has to go up. A lot of people just cannot pay the taxes, and they had to sell this land.

See. . . we get drinking water from Cape Fear River, and people who voted for County water they say, “Well, this is going to be great. We go get clean water.”

What did they do? Run it all the way down to Calabash, to the ends of the county. And the people on the North side of the road is barely beginning to get a spare from water now. Barely. Just a very few people. They voted for water, but they don’t get no water. It’s Holden Beach got plenty of water. I mean, I got water because they were trying to get it to Holden Beach. They didn’t run it by here for me.

So tourism and development have changed things.

Everything. Everything. The inshore fishermens and the offshore fishermens would have been better off to have never sold a foot of land to tourists. Because that’s the end of fishing. Because now the earth cannot absorb all the waste and pollution. It’s killing the shrimp and the oyster beds, all that. It’s not as plentiful as it was.

We just got just a few acres in the Lockwood Folly estuaries we can get oysters anymore, or clams. Just a few acres. We could fish the whole bay [Lockwood Folly] for clams and oysters. Now they’ve got a golf course down there. And of course, whenever you fertilize the golf course with all the nitrogen to keep to keep the grass green, that’s bad for the estuary.

BUILDING A BOAT AND BECOMING A SHRIMPER

Tell me about your boat.

I always wanted a steady job. Something I could depend on. And that’s when I started the boat.

While I was unemployed, I’d go by the scrap yard and buy scrap iron and bring it home, because I know that’s going to be on the boat. I built all that stuff out of scrap. If you look halfway up the mast you see two different sizes of pipe… They had about 20 foot of one piece and 20 foot of another piece. So, I married them together and made it as tall as it’s supposed to be.

And that was during 1971. Every week, whenever I go to sign up for unemployment, I’d stop by and get scrap shackles and iron. Angle iron. And all kinds of stuff.

And we worked night and day from then for six months building that boat. The Morning Light. That’s what we named it in. The Morning Light.

You worked all day, nine hours a day. You were ready to go to bed whenever you got home, but I couldn’t go. Because when I got home, my wife had supper cooked. And I’d come in, I’d leave, I’d eat and go out there, start welding.

We had to borrow some money. And I’ll use the word luck — I don’t use that word too many times — that I had a good bank that stood up for me with the board, that I could get the money I needed to build this boat.

I had all the confidence that I could make it work. At that time there was a lot of shrimp around. There was three or four, about four different people down there building boats, selling them as fast as they could build them. They sold before they could even get it built. If I failed on the ocean, I could always sell it. Yeah, so, I wasn’t really worried about it.

We’d add a 8V 71 Detroit engine into it on the four and a half year.

When you started, were you shrimping? Is that what you did first?

No, I did the menhaden first. I could stand the ocean. So, that didn’t worry me.

See, some people can’t deal good with the water. My brother, he could not stay on the water. He just couldn’t keep his food down.

I wasn’t worried about that. But then after I got started, it was a challenge. But I liked it, because I could take care of my family. That was my main goal. I was my own boss.

They sell these sport boats for 5 or $600,000 just to go out and have fun fishing. Now, believe it or not, it’s as tough as life is on the water. It’s a hard life. When I dumped shrimp on the deck, I was just as happy as them guys pulling, that’s pulling big fish, you know? I got just as much pleasure out of dumping them shrimp on there when I had a good trip. And come back home and know everything’s okay.

And so, it took me four or five years to learn. I shrimped from Pamlico Sound to Saint Augustine, Florida, the first four years. And I was back where I started. So, then I started to go to Key West in the wintertime. And I’d stay in Key West. I’d shrimp three weeks and take one week home. And we’d leave the boat down there, you know?

We started off with a CB radio. That’s about it. In 1972 that was all there was. They did have big marine radios, but we didn’t need that. We started off with a CB radio in him that come with a VHF.

You got this little 12-foot “try net.” You pull that and determine what you’re catching and when you should take it up and when you shouldn’t take it up. When I first started, if I was dragging down, and I pulled my try net and had a good try of shrimp, I’d look on my depth record and I’d say, “I’m in 32 foot of water, so I’m going to turn around and go back.” Same trek. Well, whenever we got radar, we found out then it might be 32 foot over here, too. So we might be way off where we’re saying.

They tell me now you can hook this chart plotter up to your GPS. It’ll automatically take you down in the same trail where I used to have to steer it back down that same track. Now we had an autopilot. Even if I was dragging the boat, I could put it on autopilot… Sometimes the current would drag you out a little bit. But now they got it where it’s automatic.

A SHRIMPER’S LIFE

Was it easy selling your catch?

No problem. See, back then there was plenty of shrimp. They were small shrimp, but there was plenty of shrimp. I was in Georgia one time — this comes to mind right now — yes, off the coast of Georgia, and I didn’t know where to go to sell my shrimp. And I was talking on the CB radio, said, “I got to go find somewhere to go in to sell my shrimp.”

And before I could finish, then somebody called me back, said, “Takes 66 to channel into Georgia. We’d be happy to sell it, take the shrimp, unload the shrimp.” So, there was never no problem with selling the shrimp. Nowhere you went. And we got same thing to Pamlico Sound. No problem at all. Never.

So, you made a good living. You were able to take care of your family.

I was able to take care of my family. My main goal was in life is to take care of my family, have a decent place to live. Or listen, let’s use the word “comfortable” place. I don’t know whether I got a decent place, but I hope it’s comfortable. I didn’t need a Cadillac, you know.

Ed. Note: Harry Bryant’s son Conrad, who was present for the interview, added: “He would just get up on Sunday mornings at 3 o’clock, and he had to get the boat out there to make a drag before daylight. And then we stayed out there and worked all the way up until 11 o’clock that night, and then you would go to sleep and get up at 3 o’clock again the next morning and go start back over. He had four bins, and each bin was 900 pounds. So that was 3,600 pounds [of shrimp]. And when it was completely loaded, you couldn’t hardly read the name on the boat. So, it would be weighted.”

Harry Bryant: In Pamlico Sound, we put 38 boxes in 3.5 bins. And we carried 10,000 pounds of ice. And we carried 1,600 gallon of fuel, 500 gallon of water on a trip with us.

At that time, we was getting a pretty good price out of them.

CLIMATE CHANGE AND BAD WEATHER ESCAPES

I want to ask you about changes in the weather and the climate.

I gave Conrad a piece of property down at Havana on Lockwood’s Folly River, and he can tell you right now the tide stays higher all the time than it did whenever I built this boat. It’s higher all the time. Whenever we have storms, we have storms higher. The water table rises higher. We gets more rain in the storms.

Hurricane Floyd came by. It went up past. It went up Carolina Beach, turned around, and then come back and went across the land. And what we would do if a storm was coming, we would take the boats up [NC highway] 211 to Supply and tie them up two-abreast, and tie them off to trees, and we would come home and stay with our families until the storm went over. The trees would knock the wind off of us if we was down low enough.

Well, the next day, after the storm was over, we’d come back down the river, but the river is real crooked. We had to stay up there about four or five days, because we couldn’t find the channel to come back down the river, you know?

The water went high enough it went on 211. We went out on 211 with the 40-horse fiberglass boat. It was 18 foot. Whenever the Hurricane Floyd came, it went over the top of the rail of the bridge to 211.

In the creeks down there now, like where we go get oysters at, it don’t fall as low. Where I had the boat tied up at Beacon One fish house, he said if it keeps rising, he probably will eventually need to raise his fish house up, because you can just see visible with your eyes that the average tide is higher than what it used to be. So it’s different and it’s more severe.

Normal rain in this area is 54 inches. The record that we knew of, up until this year, was 84. That was just one year. The record. This year it was over 100 inches of rain. So definitely — you know, I don’t argue with people about what caused it. I don’t know because I’m not the scientist. But I can definitely tell you something is happening.

Let me ask you, if you can remember from your father and your grandfather, were there things that they taught you about weather?

Well, my dad didn’t recognize much extreme weather. They had moderate rains about the same time, the same thing every year. Whenever they planted their crops, their beans, I hear him say, “Well, I sure would love to see rain come.”

But we didn’t have much extreme weather at that time, and he passed on in this area here. I don’t recall very much at all.

Hurricane Hazel — nobody had seen anything like it, before or after for a long time.

I didn’t even. That was 1954.

That Friday morning we went to work. And I was working on the railroad at that time, and we all went down. The whole party went. And I got down there. I think I had a radio in the car, but I had it on the music station from Tennessee or somewhere. And we got out there, and one guy said, “This is going to take Southport off the map.”

The boss said, “Everybody wait.” You know, he was going to get the checks and bring them back to us. And he brought the checks back and passed them out.

We headed back the way we came. We got down to the Desmond Creek and the wind had not started blowing, but water was coming across the road. I thought it was just boiling out the earth it was coming so fast.

We saw a car going up the hill over the other side. We should be good to cross that creek. It was about a quarter of a mile long. So my brother — we was riding with my brother — he says to them, “We’d better not try that. We’d get washed away.” So, we turn around and come back, had to go out by Winnabow and then come down to get here and my mom’s house down there. You cross, trees start falling.

And then it tore everything up on the beach. Nobody had seen that. Everybody talks about they’d seen storms before, but some of them got their ribs broke.

The people on Ocean Isle — a whole family got lost there. One man went across Long Beach on a foam mattress. He flew cross on a foam mattress. And from then on, we had storms.

But see, that was 18, 19 years of my life I’d never seen a storm. I’d never seen storm in 19 years.

So, how do you cope with this change?

Well, it’s hard to say. I always says that I would never leave my home here, but I did leave it in this last storm. I went to Durham. Wished that I had never went.

And I’ve been in some pretty rough weather. I’ve been in waterspouts in the ocean. Hit by lightning while I was out there on the boat. That isn’t much fun. Lightning hit us in off of Georgetown in a waterspout. And then I was in another waterspout in Charleston one time. When it come by, we were catching shrimp.

You do a lot of crazy things when you’re catching shrimp. Because it gets in your head, you know. And we didn’t want to quit. But anyway, whenever we seen it coming, we knew we didn’t have enough time to go to another safe harbor or nothing at that time. So whenever we picked up the nets, we picked them up and said, “We’ve got to pick up the nets and move offshore.”

Well, we picked up the nets. And we had no idea that there was a waterspout coming. We knew that bad weather was implied once we picked them up, and the wind got to blowing hard enough that it was carrying us backwards. So I told the guys, I said, “We’ve got to pick them up a little higher, so it won’t blow our boat over the nets and get net in the wheel under the boat.”

We went back and picked up, got one more whip on them, and tied them off. By the time we got back to the wheelhouse, our boots — white boots about this high — water was running out of my boots. That’s how fast the water was. It just poured down.

When I pulled the door shut, at that moment, the lightning hit the CB antenna. And just fire was all over the room. And knocked out all my electronics on the boat. I had more than CB on there, but you could just see fire fly all around us.

You couldn’t see nothing on the radar. And it was just so much water it was just dark. The fathometer wouldn’t work, because there was so much rain hitting the water that it was too much noise that it wouldn’t receive it back.

We was in Key West one time, and we got in some bad weather there. They give out a good forecast. Like Southeast winds are getting rougher and rougher and rougher, and afterwhile the seas were building and building. And we dropped down the anchor when we worked down that night. And afterwhile we couldn’t sleep. And we pulled up the anchor and started in.

On the end of these outriggers, we got something called stabilizers. When the boat rolls over, they dive and they flatten out and slow the boat down going the other way. Well, after a while the ocean took one of them. Then the swells was coming fast enough it felt like it was going to turn over.

But anyway we put ahead in sea and decided we just had to rough it out. After a while we couldn’t keep the cabinet door shut on the boat. We brought cooking along in a gallon jug. It flew out the cabinet and fell all over the floor. My helper — he was back there, and he didn’t go to church very much. After a while I heard him back there praying: “Oh, Lord! If you let me get back home to Shallotte, I’ll go to church.” But it was rough. I mean, you could barely hang onto the wheel up there. Just it was rolling so vicious, you know.

THE CATCH — AND THE FUTURE OF SHRIMPING

Before you retired, did you see a decrease in how many shrimp were available?

The last two years. I believe 2002 we had a good year. Not everybody did, but we did. Just by luck, being in the right place at the right time.

2003 and 2004 things just got bad. The price went bad on shrimp. They got a lot of shipping in shrimp from China and South America. And the catch got lesser. So that made it very hard. Even in 2004, I had to sell my boat, because I had to come home and take care of my wife.

And a lot of boats at that time just went to pieces. People just couldn’t keep them up because of the price. See, the shipping in shrimp here from China — they could ship them in much cheaper than we could catch them, because the price of fuel went up, see. And the price of equipment just went up tremendously. Tremendous.

And then for the next 5 or 6 years, people’s boats just — they just couldn’t keep them up. They just let them go to pieces. And I said at that time, anybody who would be able to maintain during them hard times would be able to make a good living, because a lot of people would be out of business, you know.

And so far, that’s been right for the last five years. I almost wanted to cry because I wasn’t able to go shrimping. My whole 32 years of shrimping, the year Hurricane Floyd come by we caught 21-count shrimp [jumbo shrimp, 21 of which on average make a pound] off of North Carolina. Now, don’t get me wrong, we caught some 21-count shrimp in Pamlico Sound every year. But not off the coast, except that one year.

And guess what, in the last five years, they is catching 21-count shrimp by the boatloads off of North Carolina. That makes you want to go shrimping.

We’ve been talking about climate change. Evidently, the ocean temperature has changed, and they’re raising these shrimp in Chesapeake Bay. Which is a huge bay. And when the cold weather come they come out and come down to North Carolina coast.

We caught 21 counts of shrimp off of Florida back when I was shrimping. But now they’re coming out of Chesapeake, which — you cannot drag a net in Chesapeake Bay. So, they get fully grown before they even come out. So, now, if you’re working off the North Carolina coast, they’re working here now in the wintertime.

Your son Conrad doesn’t go out there catching. Do you kind of wish he was out there doing it?

Well, everybody can’t shrimp. It’s something you either love it or you hate it. You have to learn how to live with it. When you go out here shrimping, you got to put all your might in the shrimping. You have to have confidence in your boat, you have to have confidence you can shrimp.

My wife could take care of what she needed to take care of while I’m out there. I didn’t have to worry about home. I didn’t have to worry about her grocery bill, or what she spent, or whatever. I had it fixed. She could spend the house money. She could write a check out of my boat money, but she understood that’s boat money. I could calculate in my head, if I need to buy a PTO [power take-off] to go on the boat, how many thousands of dollars it cost. It was there. So I didn’t have to worry about that.

Now, like I told you, when I was in Key West, when I come home, then I spent that week with my family. I focused on them. I didn’t worry about the boat.

With Harry Bryant’s consent we excerpted and edited his interview. A recording of Melody Hunter-Pillion’s full talk with him is available here.

This interview is part of “Masters of Our Own Domain: North Carolina’s African American Farmers and Fishermen,” courtesy of the Southern Oral History Program at the UNC Center for the Study of the American South.

Special thanks to the Bryant family for the vintage photos of the Morning Light.

The contemporary photographs of the Morning Light are courtesy of Terrah Hewett, who generously has allowed us to publish them with this interview. Visit The Terrah Hewett Art Shop.

Melody Hunter-Pillion is a Global Change Fellow with the Southeast Climate Adaptation Science Center, a broadcast correspondent for ncIMPACT and PBS North Carolina, and a Ph.D. student in public history at NC State University.