IMPROVING SURVIVAL: NEW GEAR MAY HELP CATCH-AND-RELEASE FISH

This story was based on an article by Emma Fass, Virginia Sea Grant summer science writing intern.

What does a group of Sea Grant fisheries specialists do when they need to collect fisheries data?

They tap into the knowledge of the experts, such as charter boat captain Ernie Foster, who has fished off the coast of Hatteras Island for more than five decades.

“My job was to take them where I thought they would catch something,” Foster recalls. “It was a very difficult day in that the current was screaming. We had anything but ideal conditions. Bottom fishing in very deep water with a very strong current is very, very difficult, and we were still able to catch fish.”

The research team — experts from North Carolina, Virginia and New Jersey Sea Grant programs — wanted to test several experimental devices that could help reef fishes return to deep waters when they are released.

Although he didn’t use the “gizmos and gadgets,” Foster says these tools have potential.

“In looking at what they were doing on a small scale, I can see a fair number of fishermen willing to do something like that,” he notes.

There are size and harvest limits, and seasons for the fishes any angler can catch. If regulations prevent the fish from being kept, the fisherman must release it. However, some fishes need help to get away.

When anglers quickly reel in a fish from deep depths, the gas inside its swim bladder expands. Sometimes, the fish is too bloated to submerge upon release. Its expanded swim bladder acts like an inflated pool float.

This keeps the fish at the surface where it’s easy prey.

“It kills me to see a 5-pound fish floating with seagulls poking at him because he can’t get underwater,” says Skip Feller, a Virginia Beach charter captain.

This phenomenon is called barotrauma. Symptoms include bulging eyes, or organs protruding from the mouth, gills or anus.

The Sea Grant specialists collaborated with several charter boat captains in their states, including Foster and Feller, to develop and test descending devices. Their instruments were designed to bring multiple released fishes below the surface at once and improve their survival.

The National Sea Grant College Program funded the project in response to a management need expressed by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s National Marine Fisheries Service.

“We chose Sea Grant because we felt confident that it would develop a practical and reliable product that would really work on a charter boat,” says Kevin Chu, NOAA Fisheries assistant regional administrator for constituent engagement for the greater Atlantic region.

“We, like Sea Grant, are looking for ways to improve the survivorship of fish that are discarded,” Chu adds. “We asked Sea Grant to try to develop a practical method for returning multiple fish to depth, because we know that Sea Grant staff work well with the recreational fishing industry, are creative in their approaches to problem solving, and have a track record of success.”

Back to the Deep

There are many ways to help a fish get back to depth. First, there’s venting. Fishermen use a thin needle to puncture the swim bladder and release the trapped gases. Also, anglers can use single-fish descending devices to submerge one fish at a time.

But on charter boats, where a dozen or more fishes might get released at the same time, these methods are inefficient. The Sea Grant team came up with a unique solution: gear that could accommodate and lower many fishes at once to keep up with the high volume of fishing activity.

The ideal device would allow anglers space to fish, and would be manageable by the already busy crew. It had to be compact and easy for a mate to hand-deploy over the rail, without taking significant time away from supporting customers on board. But why bother to return a fish to depth if it’s so much trouble?

“By law, federal fishery managers must account for all fish interactions, including those that are caught and then, for whatever reason, released by anglers,” explains Scott Baker, North Carolina Sea Grant fishery specialist and one of the project collaborators.

“The number of fishes that are kept and the number of released fishes that die as a result of fishing all go toward the Annual Catch Limit or ‘quota’ for the year,” Baker continues. “Reducing the number of released fishes that die as a result of fishing should result in more fishing opportunities for anglers.”

Scientists have long assumed that fishes suffering from barotrauma did not survive after being released. However, a 2011 study funded by North Carolina Sea Grant found that this supposition overestimated fish mortality.

The researchers — led by North Carolina commercial fisherman Tom Burgess and Jeffrey Buckel, a fisheries biologist who is on faculty at North Carolina State University — studied the effects of barotrauma on black sea bass that were captured at depths common to the fishery. They discovered that the majority of the sea bass that made it down to depth survived.

“Black sea bass was an ideal candidate for the research because the species can suffer from barotrauma, and a high percentage of recreationally caught fish are released by anglers,” Baker notes.

Black sea bass that swam down — whether or not they showed signs of barotrauma — had a 93 percent survival rate, while only 17 percent of the fish that floated survived, the final project report noted.

“Thus, our study supports the conclusion that swimming down after release is a reasonably good indication of survival in black sea bass,” they wrote. To view their final report, go to ncseagrant.ncsu.edu/search and look for 2011-FEG-04 in the Project Number field.

The South Atlantic Fishery Management Council applied this estimate of discard survival to the black sea bass population in the South Atlantic.

Designing a Solution

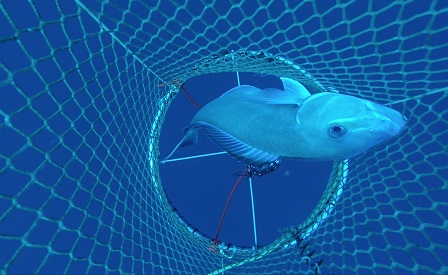

With input from captains, the research team designed several different devices and tested multiple prototypes. For their study in winter and spring 2015, they tested a weighted hoop-net device.

The device is a tubular net, with one end closed and the other open. As anglers catch fishes, they put the ones they want to release into the net. To release the fishes, the hoop-net is dropped overboard. The device falls through the water with the opening facing down. The weight of the hoop pulls the net down, fishes and all.

“Each fish is like a balloon and has a buoyancy factor that must be countered,” explains Bob Fisher, with Virginia Institute of Marine Science extension. He is affiliated with Virginia Sea Grant and one of the researchers on the team.

The hoop must weigh enough to sink, despite the little fish “balloons” floating in the net. The fish’s swim bladder recompresses as it is pulled down, and the fish regains the ability to swim out on its own.

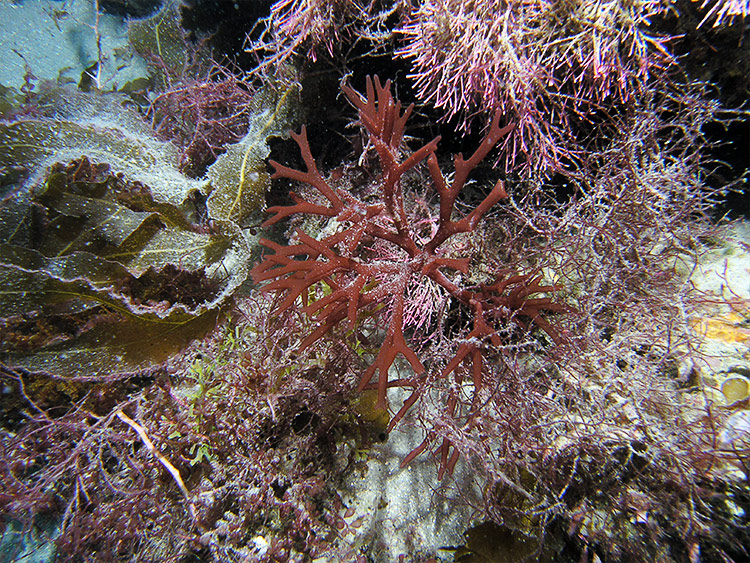

The team tested the design on several species including blueline tilefish, triggerfish, blackbellied rosefish and black sea bass — which they encountered the most.

“From what we can tell, it works. It’s relatively easy. It’s quick. It doesn’t take up a lot of space. It has all the pluses in terms of use and time and space,” says Michael Danko, assistant director for extension for the New Jersey Sea Grant Consortium and another member of the research team. “We need to do more tagging to find out if the device is actually effective.”

The researchers descended a total of 227 fish. Of those, 161 fish — including 61 in North Carolina — were tagged and will be monitored by tagging programs in each state. Recapture of those fishes will help researchers estimate how well descending devices improve survival.

“It’s a great tool, but it’s going to be one of many tools,” Danko predicts. “There’s no one set tool or device that everybody can use.”

During trials, the Sea Grant specialists also discussed barotrauma with anglers, and gauged their opinions about using the descending devices. See the story by Sara Mirabilio, North Carolina Sea Grant fisheries specialist and another team member, for more on the education and outreach portion of this study.

While the trials were promising, there’s still work ahead to get captain and angler buy in.

“Getting fishermen — recreational anglers and commercial fishermen too — to use stuff like that is challenging,” Foster says. “But I think the way Sea Grant goes about it, where they work cooperatively with boats rather than order them around, it has potential.”

Go to youtu.be/fREWb8kwRcE for a three-minute video that explains barotrauma. The final report is available at go.ncsu.edu/nvuw10.

This article was published in the Holiday 2015 issue of Coastwatch.

For contact information and reprint requests, visit ncseagrant.ncsu.edu/coastwatch/contact/.

- Categories: