ISLANDS IN CONTRAST: Exploring Southern Barrier Islands

Within sight of luxury resorts and bustling coastal communities lies a virtually deserted island. No buildings. No running water. No amenities. Masonboro Island is as pristine as it gets.

Still — or perhaps for that reason — some 45 adventurous men and women step onto the sandy shore to explore the uninhabited barrier island for what will be a day of sand, sea and science.

North Carolina Sea Grant’s Lundie Spence and Walter Clark lead the chattering contingency from the Encore Center for Lifelong Enrichment at North Carolina State University. The mission is to learn about a trio of barrier islands clustered along the state’s southern coast — Masonboro Island, Bald Head Island and Wrightsville Beach.

The field study will highlight the respective island differences — one under conservation protection, one in the process of being developed, and another that is fully developed.

Spence, Sea Grant’s education specialist, will tell the ecological, geological and biological story of the natural processes at work in the complex coastal system.

Clark, coastal law specialist, will show that increased human interaction with the environment often results in increased policy concerns. For example, while Wrightsville Beach may be fully developed, public policy guarantees access to its oceanfront beaches.

Bald Head is a unique private-public experiment that marries the protection of natural and historic areas with controlled development of this lush, subtropical island.

“Masonboro Island, on the other hand, represents the ultimate policy decision by the state to purchase the property and hold it in perpetuity,” Clark says. One of the last wholly undeveloped barrier islands along the southern coast of North Carolina, it is under the protection of the North Carolina National Estuarine Research Reserve System.

“Masonboro Island belongs to all the people of the state. It is a living laboratory for all who are interested in marine ecology and science,” Clark adds.

Learn as you go

Betty Poulton, Encore special programs coordinator, has seen to every detail of the three-day experience so that participants broaden their understanding of the natural resources as well as the history of coastal North Carolina.

Encore field trips are never run-of-the mill sightseeing excursions. Destinations must meet Encore expectations for programs that foster intellectual stimulation and community involvement, says Poulton.

Nature-based trips are designed to encourage a learn-as-you-go approach to environmental issues.

Pat Warner, a veteran Encore member from Raleigh, says, “We don’t take notes, and there are no tests. We have fun, learn a lot from the experiences, and come away with more than the average tourist.”

Warner adds that Encore’s environmental field studies are effective because they are well planned” … and because Lundie is an excellent show-and-tell kind of teacher. It seems that no matter what you pick up on the beach to show her, she knows about it and can relate interesting facts.”

Meanwhile on Masonboro Island, the men and women are beginning to discover indigenous “wildlife.”

Ghost crabs scurry and disappear beneath the sandy shoreline, prompting one man to ask, “What use is this tiny critter?”

Spence explains that the lowly ghost crab is an important player in nature’s balancing act — the food chain. Some marine biologists say that ghost crabs could be casualties of beach renourishment programs if they are buried by sand that is unsuitable for burrowing. The scientists fear the loss could lead to decreasing numbers of shore birds that depend on ghost crabs for food.

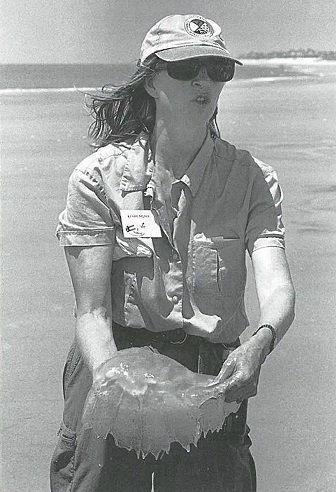

A number of horseshoe crabs along the shore present another teachable moment. Blood from this ancient sea creature is used for medical research, Spence explains.

Horseshoe crabs have become the center of controversy in some mid-Atlantic states, especially Virginia and Delaware. The federal government is enforcing catch limits, pointing to research that suggests that overharvesting will have an impact on migrating shorebirds that feed on horseshoe crab eggs during their spring migration. Horseshoe crabs live in coastal waters, but move inshore during the spring to spawn in estuaries and along shorelines.

However, Virginia’s whelk fishery proponents say that catch limits will devastate their industry, which uses horseshoe crabs for bait.

More lessons from the sea

The island has still more lessons to reveal. At low tide, a break is forming in a nearshore sand bar, setting up conditions for a deadly rip current. Sure enough, Spence spots the telltale signs: an offshore plume of turbid water just past the sandbars; foam moving seaward; choppier waves and murky water within the rip current.

Even the most powerful swimmer can get caught in a rip current, Spence says. She tells the group that the most important thing to remember is to keep calm. “Don’t panic.

Don’t try to swim against the current,” she warns. “Swim parallel to shore until you are out of the current. They are usually no more than 30 feet wide.”

A walk across the low-profile dunes is an opportunity to inventory adaptive vegetation that helps capture moving sand and anchor the shifting island: grasses, yucca, sea rockets, seaside evening primrose, seaside goldenrod, and poor man’s pepper. Bird watchers look for brown pelicans, black skimmers, American oyster-catchers and willets.

Even waiting for the boat for the return trip is not wasted. Spence explains that the marshes and surrounding waters are nurseries for juvenile shrimp and fish. The sound area of the island accounts for about $350,000 in commercial fish and shellfish annual production.

There’s also time to demonstrate the art of keyhole clamming at the water’s edge. This technique involves spotting the unique-shaped holes left in the sand by clams as they filter water. No special gear is needed — just a keen eye and a willingness to get a little muddy. To spare hands or feet from sand abrasion, some prefer to use a rake.

Clark also has time to talk about the jetties — one on the northern end of Masonboro and its mate on the southern end of the Wrightsville Beach island. The jetties keep the channel open from the ocean to the Intracoastal Waterway. Sand pulled along the Wrightsville Beach oceanfront is trapped by the north jetty at the expense of Masonboro Island. Increased erosion contributes to the island’s susceptibility to overwash —resulting in an ever-changing island profile as sand is earned over and deposited onto the landward shore of the narrow barrier island.

He uses the dynamic nature of Masonboro Island to discuss coastal building policies. According to the Coastal Area Management Act (CAMA), single family homes must be set back from the first stable line of vegetation at a distance equal to 30 times the historic annual rate of erosion. Buildings with more than 5,000 square feet must be set back at a distance equal to 60 times the erosion rate.

The Shell Island Conundrum

After the brief charter boat trip across the channel, the class reconvenes at the Shell Island resort on the northernmost tip of the Wrightsville Beach island. They see a dramatic illustration of what happens when human plans collide with the forces of nature. Since the high-rise complex was built in 1984, Mason Inlet has migrated southward, threatening the nine-story building and other nearby properties.

Clark explains that one proposal on the table is to move Mason Inlet 3,000 feet to its 1986 position. Such a project involves a host of environmental, legal and financial issues.

Nature has written many chapters in the history of the Wrightsville Beach island, which has been a mecca for fishing, boating and beach lovers for more than a century. Its popularity soared in the late 1800s with the construction of a road and trolley line connecting Wilmington and Wrightsville. Since then, the great hurricane of 1899 and hurricanes Hazel, Bertha and Fran claimed lives, sheared back dunes and leveled homes and businesses.

Hurricanes and nor’easters have contributed to the ever-changing configuration of not only Wrightsville Beach, but all of the state’s barrier islands.

Almost paradise

The day on the primitive, no-frills Masonboro Island was a marked contrast to the previous day’s journey to a 2,000-acre, active resort island community Almost paradise The day on the primitive, no-frills Masonboro Island was a marked contrast to the previous day’s journey to a 2,000-acre, active resort island community — Bald Head Island.

The island is endowed with a maritime forest, salt marshes, miles of ocean beaches and a rich, but stormy, maritime history. Bald Head Island is part of the historic Smith Island complex, which includes Bluff Island and Middle Island.

Located between the Atlantic Ocean and the mouth of the Cape Fear River, the forested barrier island is the northernmost subtropical island on the Atlantic coast. It is accessible only by private boat or ferry service. On the island, transportation is by golf carts, trams, bicycles or foot.

The Encore entourage boarded a convoy of golf carts for the short drive to Bald Head Island.

The island is endowed with a maritime forest, salt marshes, miles of ocean beaches and a rich, but stormy, maritime history. Bald Head Island is part of the historic Smith Island complex, which includes Bluff Island and Middle Island.

Located between the Atlantic Ocean and the mouth of the Cape Fear River, the forested barrier island is the northernmost subtropical island on the Atlantic coast. It is accessible only by private boat or ferry service. On the island, transportation is by golf carts, trams, bicycles or foot.

The Encore entourage boarded a convoy of golf carts for the short drive to the east end of Federal Road to reach the Bald Head Conservancy headquarters. There, Gil Powell, conservancy executive director, spoke of ways the organization is working to preserve the island’s natural resources and to promote stewardship of the surrounding coastal environment. The conservancy sponsors scientific research and provides environmental education programs.

It is known nationally for the Sea Turtle Protection Program, Powell said. From May through October, Bald Head beaches are nesting sites for sea turtles. Interns from university marine studies programs and volunteers patrol the beaches to record and protect nesting sites. Bald Head volunteers have helped collect scientific data to track turtle nesting trends for nearly two decades.

The conservancy also conducts camps for youngsters and trains volunteers to become part of the protection effort.

Though Powell claims not to be a professional naturalist, he can rattle off turtle facts with the best of graduate students. Conservation has become his avocation and he hopes to learn more about sea turtles from a joint project with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. Researchers will do pre- and post-beach nourishment surveys to determine what — if any —impact sand placement has on sea turtle nesting habits along the coast.

“Turtles and humans have a lot in common,” Powell quipped. “We both like oceanfront property. It seems that more and more they are in competition with humans for habitat.”

Research, he believes, is essential. “Think about it. Turtles have been around for more than 50 million years. They managed to survive whatever killed the dinosaur. It’s only within the past 50 years that they have been in trouble.”

Some harmful human interactions are easy to spot, he said, picking up a plastic milk jug. “Floating in the ocean, it looks like a juicy jelly fish. That mistaken identity means certain death for turtles.”

Triple dose of nature

Virginia Smith, an octogenarian Encore member, is a beach lover from way back. She has fished from piers and inlets, camped, walked beaches and explored maritime forests all along the North Carolina coast.

“I’ve seen a lot of changes — some by people and some by nature. I admire the work the conservancy is doing here. They and other groups are doing marvelous things to preserve our resources at the coast.”

Bald Head presented beach, maritime forest and salt marsh environments for Smith and her Encore colleagues to observe. Beachcombing turned up jelly fish, whelk egg cases and other treasures. The maritime forest spoke to the survival traits of 400-year-old live oak trees. And the salt marshes displayed an array of adaptive plant specimens — cord grass, black needle rush, sedges, sea lavender, cotton bush, red cedar, myrtle and yaupon holly.

A weathered, 1900-era boat house on nearby Bald Head Creek gave testimony to the dynamics of nature at work on the island. Over time, the creek changed course, stranding the structure in the middle of the marsh — a lesson not lost on members of the Encore group.

Reflecting on the field study experience, Spence, who has led a number of Encore field trips, says she enjoys working with “perceptive adults with a wide range of life experiences.”

She adds, “This more mature and experienced audience understands how processes and policy work together; that the history and culture of the islands form and shape policy; and that you can’t separate science and public policy.”

For information about: Encore programs, call 919-515-5782; Masonboro Island, contact John Taggart at the North Carolina National Estuarine Research Reserve Program, 910-962-2470; and Bald Head Island Conservancy, call 910-457-5786.

Old Baldy is Beacon of History

Bald Head Lighthouse — established in 1817 — is the oldest lighthouse on the North Carolina Coast. But it was not the first or the last to shine a guiding beacon from the island’s shores. Barrier island dynamics wrote much of its history.

The first Bald Head Light was constructed in 1794 on the banks of the Cape Fear River. Too close to the river, as it turned out. Erosion took its toll, and the lighthouse fell into the river.

When Old Baldy was completed in 1818, it was to light the way for ships at the mouth of the Cape Fear River until 1866.

As shoaling reshaped the inlet, the beacon shifted to Federal Point at the north entrance to the river. Continued shoaling closed the New Inlet in 1880, and the Federal Point Light was decommissioned.

Old Baldy shone again from the southwest bank of the river’s entrance until it was decommissioned in 1935.

The channel through the Cape Fear continued to change, giving rise to the need for an additional coastal light to aid navigation to and from the Wilmington port. In 1903 the Cape Fear Light was constructed on a hill overlooking Frying Pan Shoals near the ocean at the end of Federal Road.

A concrete base is all that is left of that tower today. But nearby stands Capt. Charlie’s Station — three simple, clapboard cottages that housed Capt. Charlie Swan, lighthouse keepers, and their families. Capt. Charlie tended the Cape Fear Light until 1933.

The inlet continued to shift. The Cape Fear Light’s skeleton tower came down in 1958 when the U.S. Coast Guard turned on the powerful beam of Oak Island Lighthouse from the opposite shore of the Cape Fear River.

But Old Baldy remains an island landmark. Its octagonal tower reflects an early lighthouse architectural style. The Old Baldy Foundation oversees the preservation and maintenance of the lighthouse, which is listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

The foundation restored the lighthouse and opened it to the public in 1995. Last spring, members dedicated the Smith Island Museum of History, a replica of an 1850s lighthouse keeper’s cottage built in the shadow of Old Baldy.

Jane Oakley, foundation executive director, said members will continue efforts to recover pieces of the island’s history.

Much of the Bald Head Island’s history is colored by its strategic position. Bald Head Island played a vital role in protecting the Wilmington port during the Civil War, the U.S. Lifesaving Service established the Cape Fear Station on the island’s east beach in 1882; and the U.S. Coast Guard was posted on the island during World War II.

Today, Bald Head Island is residential and resort island community accessible by private boat or a passenger ferry from Southport. For additional information, call 800-234-1666.

This article was published in the Autumn 2000 issue of Coastwatch.

For contact information and reprint requests, visit ncseagrant.ncsu.edu/coastwatch/contact/.

- Categories: