“Always, then, in this flotsam and jetsam of the tide lines, we are reminded that a strange and different world lies offshore.”

From The Edge of the Sea by Rachel Carson

Every so often, when the whims of wind and water coincide, tiny travelers bearing history, myth and mystery come ashore in North Carolina.

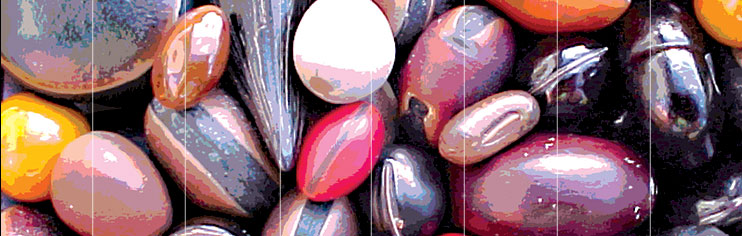

These little ocean-going envoys are called sea beans, and though many of them really are beans, they do not come from the sea itself. They are seeds fom tropical vines, plants and trees that grow in faraway rain forests. They fall into the streams and rivers of the lower latitudes, and the water carries them to the oceans. There, sea beans can float with the currents for hundreds or thousands of miles, and for many months, sometimes years.

When the tides land them on our sands, they become the delight of discerning beachcombers who have learned to look for more than seashells.

“They could be from almost anywhere in the world,” says sea bean collector Sherry White of Morehead City. “That’s part of the fascination. Your imagination can just run wild.”

Sea beans, indeed, have been firing imaginations worldwide for centuries. Early Europeans thought these drift seeds floated up from underwater forests, and believed them endowed with curative — even magical — powers.

Certain sea beans have a curious countenance adding to their appeal. The hamburger bean, from vines along the Amazon, looks just like the entree but for its dollhouse dimensions. In some countries, it’s called a horse eye. One would expect the sea purse to snap open and spill out minute coins. Costa Rica’s monkey ladder vine produces the valentine-shaped sea heart. Mary’s bean, also called a crucifixion bean, bears the impression of a cross on one side and a womb-like image on the other.

These and more can be found on North Carolina shores. The book, World Guide to Tropical Drift Seeds and Fruits, says 22 varieties have been counted in the Carolinas.

But because most sea beans are brown and small and wash in with seaweed and other flotsam, they are easily overlooked. And many people, like White, publicity coordinator for the North Carolina Aquarium at Pine Knoll Shores, don’t know what they’ve found when they encounter their first sea bean. A sea heart she discovered at Cape Lookout about 10 years ago piqued her curiosity. She was fascinated when she learned what it was.

“The mystery is what’s intriguing,” she says. “And how far they travel.”

A WORLD VIEW

Sea beans come our way from the Caribbean, South America, Central America and the southernmost Florida Keys thanks largely to the Gulf Stream, the north-flowing river within the Atlantic off the East Coast. The beans turn up as far north as Cape Cod, though they become increasingly rare north of Cape Hatteras. Southeastern Florida beaches, on the other hand, are a collector’s paradise, given the proximity to the sources.

Some sea beans are trans-Atlantic voyagers, reaching the United Kingdom, Norway, Greenland and Iceland. In the days before ocean currents were understood, sea beans gave rise to much lore and legend, as well as practical or medicinal uses.

The sea heart is said to have a hand in world history, inspiring Columbus to search for the lands to the west whence they came. The sea heart is still called the Columbus Bean in the Azores, some 800 miles off the coast of Portugal.

The Irish put sea beans under pillows to keep the mischievous “little people” away. On Scotland’s Hebrides islands, sea pearls, also called nickernuts, were worn to ward off evil. Mary’s bean held special meaning for the devout, and the expectant. Hebridean mothers in labor clutched a Mary’s bean in hopes of an easy delivery and a healthy infant.

In old England, sea hearts were good luck charms for seafarers because they had weathered a long ocean journey. Babies teethed on the flint-hard coating of the seed, about the size of a silver dollar. Early Norwegians brewed a tea from the sea heart husk for women giving birth, and made medicine for cattle from the bean’s insides. Some folks halved sea hearts, hinged the joint and made them into snuff boxes. In modern times, some collectors polish sea beans for jewelry. Others puncture the outer coating and cultivate the seeds into indoor plants. Most, though, simply keep them as reminders of the ocean’s wonder and the lands that beckon beyond the horizon.

ANY DAY CAN BE BEAN SEASON

Unlike seashells, sea beans are not an everyday find on North Carolina strands. A dedicated beachcomber might pocket only a few per year, making them all the more special, some say.

“I think that’s the wonderful thing about sea beans,” says Capt. Ron White of Morehead City, who conducts ecological sailing charters to Cape Lookout National Seashore. A marine biologist, he also has sailed Caribbean and Florida waters, and gathered dozens of sea beans since his father gave him a lucky bean — a sea heart — from Cuba as a child.

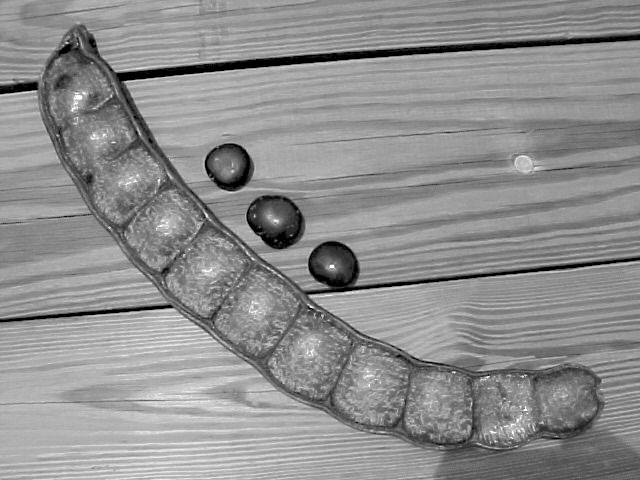

When a strong southwest wind sends ashore the sargassum often floating in the Gulf Stream, White says, he looks for sea beans. The variety he finds most often is the sea coconut — a dark, round, lightweight palm seed, also called a golf ball, that grows in threesomes in a knobby capsule. Sea coconuts, sometimes still in their peculiar-looking pods, and other sea beans float a little higher than the seaweed.

“A strong southwest wind in the summer can bring in a treasure trove,” he says. “If you look above the weed line, you’ll find them.”

While sea beans often ride in on a strong wind or a storm tide, offshore conditions can bring them on a calm day as well. Some Floridians consider fall sea bean season — some plants shed their seeds then, and hurricanes stir up the waters. Because they can drift for months, however, sea beans can appear year-round.

LOOKOUT FOR SEA BEANS

North Carolina’s northernmost and southernmost beaches both sometimes have sea beans, according to the state aquariums at Roanoke Island and Fort Fisher. By most accounts, though, the currents are kindest to collectors around Cape Lookout. The Gulf Stream comes closest to our coast there, and its dynamics make surrounding beaches the destination for tropical tidbits.

“The stream is really a strongly meandering set of flows, with some meanders forming eddies that spin away from the main axis of flow,” says Larry Cahoon, a North Carolina Sea Grant researcher specializing in biological oceanography at the University of North Carolina at Wilmington.

“The force of the stream also creates counterclockwise-moving flows in the coastal bays, such as Onslow Bay, the shelf waters between Capes Lookout and Fear,” Cahoon says. “The Gulf Stream meanders that get entrained in the counterclockwise flows in shelf waters carry tropical water and flotsam inshore at Cape Lookout, which is why we see lots of tropical stuff in that area.”

Near Hatteras, the Gulf Stream veers away from the coast, and conflicting currents tend to push floating objects out to sea. But many variables of wind and current can bring sea beans and other surprises from far-flung shores onto the beach almost anywhere.

Even at Cape Lookout, sea beans are something special. “You may find them once during the season when winds are right or storms are right or you just happen to be in the right place,” says Cape Lookout National Seashore park ranger Karen Duggan. “They’re wonderful little reminders of things to the South. We just don’t get them often.”

A MESSAGE IN A BEAN

Why sea beans travel so far from the tropics, when they cannot survive cold climates, is nature’s secret. Perhaps the plants are expanding their range by indiscriminately sending seeds to sea, equipped for a long and wet passage. Some float because of a lightweight, fibrous coating; others have an air pocket inside a casing so hard that early Scandinavians thought sea beans were stones.

Whatever their reasons for their long journeys, sea beans continue to intrigue their finders, just as they have for centuries.

“Sea beans are among those things that regularly — not ten times a week but at least a few times a year — somebody will bring in and say, ‘What is this?'” says Bob Patton, education curator at the North Carolina Aquarium at Pine Knoll Shores. He himself has found a few known sea beans, and a large, mysterious seedpod he has not yet identified.

A sea bean on the beach, he says, holds the same sort of mystique as a message in a bottle.

“You wonder how long has it been out there,” he says, “and where did it come from?”

FOR MORE INFORMATION:

- www.seabean.com has sea bean background and details on the Eighth Annual International Sea Bean Symposium and Beachcombers’ Festival, Oct. 10-11, Cocoa Beach, Fla.

- The Drifting Seed newsletter, P.O. Box 510366, Melbourne, FL 32951; also available on www.seabean.com.

- The Little Book of Sea-Beans and Other Beach Treasures, Cathie Katz and Paul Mikkelsen, a pocket guide available through the sea bean Web site.

- World Guide to Tropical Drift Seeds and Fruits, Charles R. Gunn and John V. Dennis, revised edition, 1999, Krieger Publishing Co., P.O. Box 9542, Melbourne, FL, 32902-9542; phone: 321/724-9542; www.krieger-publishing.com.

- Sea Beans from the Tropics, Edward L. Perry and John V. Dennis, 2003, Krieger Publishing Co., P.O. Box 9542, Melbourne, FL, 32902-9542; phone: 321/724-9542; www.krieger-publishing.com.

This article was published in the High Season 2003 issue of Coastwatch.

For contact information and reprint requests, visit ncseagrant.ncsu.edu/coastwatch/contact/.

- Categories: