Janna Sasser recently graduated from North Carolina State University with a degree in communication and a minor in journalism.

Standing at the end of a dock on the Neuse River, a young John Fear would cast, wait for a bite, and soon feel the thrilling tug at the end of the line.

Reeling in the olive, snake-like body — its skin thick and slimy — he’d plop the young eel in a bucket, and cast again.

“I could catch them left and right,” he recalls. “I had no idea what they were, but I knew they had teeth.”

Today, Fear is an estuarine biogeochemist and North Carolina Sea Grant deputy director — and the chances of catching an American eel, Anguilla rostrata, are slim. The rivers and streams of eastern North America, once coursing with spring runs of eels, now are nearing historically low levels of these fish.

“The decline of American eel populations raises a concern about the health of our tidal creek habitats,” Fear adds.

The most recent stock assessment by the Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission, or ASMFC, in 2012 noted that the American eel stock was depleted in United States waters after drastic declines in recent decades.

“Despite population declines along the Atlantic Coast, there are no demographic rates and surprisingly little basic demographic data on American eel populations for the southeast United States,” notes Paul Rudershausen, a doctoral candidate at North Carolina State University’s Center for Marine Sciences and Technology, or CMAST.

With funding from Sea Grant, Rudershausen is working with project lead Jeffrey Buckel, a fisheries biologist at CMAST, to study the stock status of eels in North Carolina tidal creeks.

Juvenile American eels are commonly found in estuarine regions, some moving inland to settle in freshwater streams, and others making homes in brackish or saltwater habitats.

Once establishing a home range, they may live undisturbed in forgotten pools for decades. Rudershausen is interested in the demographic trends of eels — changes in the eel population over time.

“There seems to be a lot of disagreement about the status of this species,” he explains. “A literature search on the demographics of American eels along the Atlantic Coast reveals almost no information on a species that’s historically been very important — and now, by most accounts, on a dramatic decline.”

The goal of the project, Buckel notes, is to relate demographic rates with different attributes of urbanization. “For example, if one creek is more urbanized than another, we can compare abundance and survival rates.”

In 2015, the team began sampling for juvenile eels in the tidal creeks of Carteret County. Using six different sites, they are studying habitat factors that may affect the survival rate of American eels.

SLIPPERY BUSINESS

In an era when the chromosomes of many organisms are mapped and sequenced, much about the biology and behaviors of American eels remains a mystery.

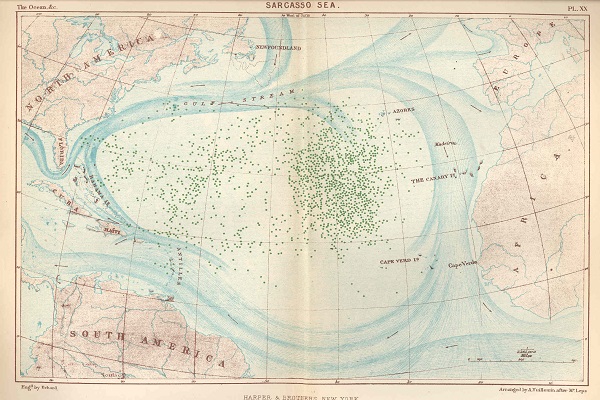

There are a few things known about eels. All eels found in eastern North America and in Europe hatch in the Sargasso Sea. They are carried by ocean currents to the mouths of rivers, where they begin their journey upstream. Most of their life is spent inhabiting creeks and rivers until eventually returning to the Sargasso, where they lay eggs and die.

This is the consensus among biologists and naturalists today, although no adult eel had ever been found swimming, reproducing or dying in the Sargasso Sea until 2015. That year, a team of researchers in Canada successfully tracked one adult eel from the coast of Nova Scotia to the northern limit of the spawning area in the Sargasso, near Bermuda.

“That’s the first actual documentation of an adult eel making the trip,” Buckel notes. “Until then, everyone just speculated that’s what happened because that’s where you find American eel larvae, so they knew adults had to be there.”

Several dozen others tagged were never documented beyond the Gulf Stream.“

American eels are catadromous, meaning they hatch in the ocean, mature in fresh water and migrate back to the ocean to spawn,” explains Thomas Fenske, curator of fish and invertebrates at the North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences.

The species extends from Greenland to northern South America, Rudershausen notes. “All adult eels from those freshwater rivers go to the Sargasso Sea to spawn,” he says. Because of this unique cycle — with every American eel coming from the same grounds, and returning there to spawn — American eels are considered to be one “stock.”

The Sargasso Sea is strange and unique in itself. Lying deep within the Atlantic near Bermuda, it’s the only sea with no land border. Instead, its body of encircling currents is defined by other major ocean currents, such as the Gulf Stream to the west.

With no coastline, the waters are uncannily calm, and remain warmer and saltier than surrounding waters. And it is vast. The Sargasso Sea stretches approximately 700 miles east to west and 2,000 miles north to south, and is canopied by large, floating mats of golden Sargassum seaweed.

American eels journey thousands of miles to spawn in these waters, retracing the route they took as larvae. In preparation for the return journey, sexually mature females gorge themselves, Fenske notes, changing color from muddy yellow-green to dark green on top and snow white on their bellies.

Once reaching estuarine waters, the first leg of their journey completed, they never eat again. Their pupils expand and turn blue, adapting to new sight for the depths of the sea.

“They follow the Gulf Stream to the Sargasso,” Fenske explains. “Once there, they release thousands of eggs for the males to fertilize, and then die from exhaustion and starvation.”

Though spawning activity remains undocumented, larval eels — flat, transparent and the shape of a willow leaf — are found floating and swimming in these waters for months before passively drifting with the ocean currents, riding the Gulf Stream to the eastern coast of the Americas.

At this stage, the leptocephali, or larval eels, are barely more than a thin layer of muscle housing a clear, jelly-like substance. They have a simple tube gut and a small, pointed head with teeth.

“When they sense fresh water close by, the eels metamorphose and begin actively swimming toward the coast,” Fenske explains.

Juvenile glass eels — sinuous ribbons merely inches long and clear as glass — reach the coast after approximately a year, swarming into the mouths of estuaries by the millions.

Upon arriving, they develop brown pigmentation, a camouflage in the murky water, and are known as elvers. “They continue to develop slowly, their changes occurring as salinity decreases,” Fenske explains.

The young eels spend the majority of their life inhabiting inland streams, ponds and rivers as they mature. They continue upstream — sometimes moving as far inland as the Mississippi River — until something tells them they’ve reached home. They may live there up to 30 years, Buckel notes, burrowed under stones and logs by day, and surfacing to roam and feed at night.

This period spent in freshwater and estuarine environments is crucial for the maturing eel. It will transform from an elver — merely inches long and barely pigmented — to a yellow eel, growing up to 3 feet and becoming mottled yellow and olive. It will stay here, feeding, growing, swelling and darkening until reaching sexual maturity. Then it heads downstream, ready to return to its spawning grounds.

GETTING TO THE BOTTOM OF TIDAL CREEKS

The research in Carteret County’s tidal creeks stems from Sea Grant’s 2014 Research Symposium, titled Investments and Opportunities.

“Our stakeholders identified particular areas of the state’s coastal needs,” Fear recalls. “This project ranked high and fit into one of those categories — tidal creek systems.”

These creeks provide pathways for American eels as they journey from their natal ocean waters. For some, the creeks are home until making their return trip.

Tidal creeks begin in upland areas and drain into larger creeks, which connect to estuaries and the ocean. They are links between land and estuary, transporting organisms and nutrients with flooding and ebbing tides. They also transport pollutants.

“Often, upper portions on headwaters of tidal creeks are underappreciated, but important to consider,” notes Gloria Putnam, Sea Grant coastal resources and communities specialist. “They are complex, ever-changing systems, and on low tides, can be a harsh place for humans,” she adds, “yet they provide homes to unique species that are becoming scarce.”

These landscapes are highly prone to degradation due to their proximity to the uplands they drain. “People want to develop on or around the water, so these systems are often moderately to highly impacted,” Putnam explains.

Putnam joined Rudershausen and Buckel during a sampling trip in April. “I was surprised to learn eels would migrate up to and live in these shallow, narrow portions of creeks — areas that many might consider useless,” she recalls.

Twice monthly, the team deploys baited minnow traps in each of the creeks. Captured eels are anesthetized, measured and weighed before being tagged with a transponder device. Transceiver systems installed within the creeks detect the tags, and from the data, the researchers can estimate daily survival rates of the tagged eels.

Several of the creeks run through residential neighborhoods, or hide behind busy, developed highways. These creeks, found in the midst of Morehead City’s industrialized areas, are particularly vulnerable to habitat degradation, with minimal vegetation to buffer the effects of runoff from nearby development.

A few sites, however, have relatively natural habitats, bounded by salt marsh with nearby vegetated areas.

“We’re sampling across a range of development impacts that are being experienced along the Carolina coastline,” Rudershausen says.

And that’s by design, Buckel adds. “Our sampling sites provide a determination of what habitat types are important to yellow-phase eels,” he notes.

“At the end of the project, we’ll be able to test what habitat factors are important to juvenile eels’ presence or absence at each site.”

RELATED EEL RESEARCH

North Carolina Sea Grant has supported other eel research, including:

- Roger Rulifson of East Carolina University collected American eel sex ratio and relative abundance data from Lake Mattamuskeet and the Pamlico Sound in 2004. Research results informed management strategies at Mattamuskeet National Wildlife Refuge, and raised local residents’ awareness of the American eel stock’s potential decline.

- In 1999, a UNCW team studied American eels in the Cape Fear River, and found that the parasite Anguillicolo crassus may be responsible for declines in the Cape Fear River population.

- A 1997 study led by Wesley Patrick of the University of North Carolina Wilmington investigated occurrences of the parasite Anguillicolo crassus in American eels in North Carolina.

This article was published in the Autumn 2016 issue of Coastwatch.

For contact information and reprint requests, visit ncseagrant.ncsu.edu/coastwatch/contact/.

- Categories: