OCRACOKE ISLAND: Teachers Explore Unique Culture

While leading a group of teachers down a tree-lined back road on the Outer Banks barrier island of Ocracoke, Alton Ballance stops at a special spot that will be forever British.

Leaning over a white picket fence surrounding the British Cemetery, Ballance points to four simple gravestones. Then he recounts his kinfolks’ tales of the victims.

“My relatives used to tell stories about hearing torpedoes go off, and the Coast Guard crew bringing in the bodies of these British soldiers,” says Ballance, author of Ocracokers. “The sailors’ bodies were washed up on the beach and buried by locals in simple coffins.”

A torpedo from a German submarine killed the soldiers stationed on the trawler H.M.S. Bedfordshire on May 7, 1942. The soldiers were guarding the coast from deadly U-boats unleashed by Adolph Hitler.

Ballance says the influx of soldiers into Ocracoke during World War II gave the Outer Banks village “its first jolt into the modem world.”

“The war forever changed Ocracoke,” he says, pointing to a Union Jack flag over the tombstones. ”It put a new face on it. When I was a boy, there was an old man from Ocean City, Maryland, who visited my grandmother and called her ‘Ma.’ He had stayed in her home during the war and came back here every summer.”

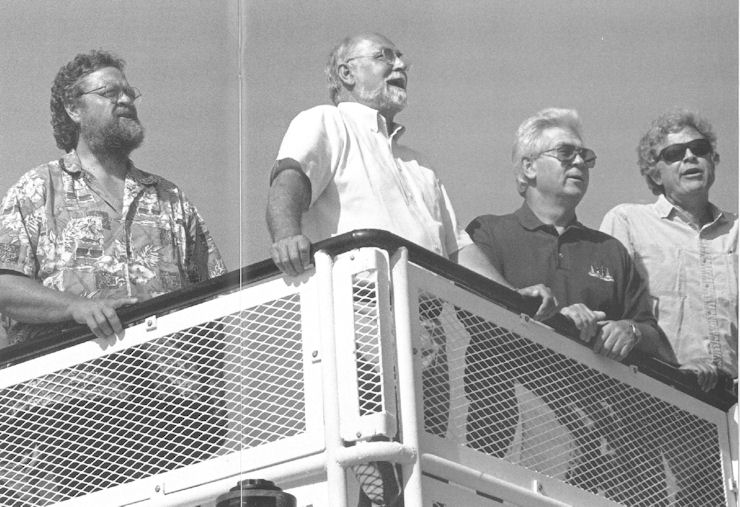

Ballance’s war tale is just one piece of Ocracoke’s rich history that he passes on to 23 teachers from across the state. For four days, the Ocracoke native, teacher, author and historian serves as a guide for the “Island People, Island Culture” seminar.

From a trek through a magical maritime forest to a tour of a striking white lighthouse, Ballance relates anecdotes and the colorful heritage of the island to the teachers.

Sponsored by the North Carolina Center for the Advancement of Teaching (NCCAT) in Cullowhee, the seminar is one of many offered by the nonprofit organization — from storytelling in North Carolina to electric vehicle technology. The seminar, which gives teachers an opportunity to renew their vitality for learning, is open to any North Carolina public school teacher employed for at least three years.

“The program allows teachers to explore new interests and ideas,” says North Carolina Sea Grant marine education specialist Lundie Spence. “It treats teachers as professionals and rewards their past efforts. The Ocracoke seminar is a prize on top of a reward.”

This is the fifth year of the Ocracoke seminar. “We chose Ocracoke as one site because it is a wonderful place to observe people’s values and roots,” says NCCAT director Mary Jo Utley. “It is a week of watching and learning about Ocracoke’s special culture and its wonderful school.”

The seminar begins in the commons area at Ocracoke School that houses students from kindergarten through 12th grade.

Built from white juniper, the room permeates with the sweet smell of cedar. Photos of old fishers peer down from one wall and smiling children from another. A mural of Blackbeard — the famed pirate who dropped anchor near the island — covers most of another wall.

“For this seminar, teachers get to meet people and hear stories about Ocracoke’s daily life,” says Ballance. “Until you sit at the table and laugh and hear stories from local people, you don’t get a full appreciation of the culture.”

As a tenth-generation Ocracoker, Ballance relates many personal experiences to the teachers – from carrying a dead body in a station wagon across the sound by ferry to teaching multiple subjects at a unique school.

“When I came back to Ocracoke School in 1982 after teaching in Orange County, I didn’t realize how demanding the job would be,” he says.

Ballance taught every subject on the high school level except math — including English, journalism, biology, health, physical education and yearbook — and coached the basketball team. Now, he teaches all high school English classes and journalism and serves as the assistant principal.

He says the small school is “like one big family.”

“In an environment where everyone knows everyone else, there is daily interaction among younger kids, older kids, teachers, family members and other people in the community,” Ballance writes in his book.

Ferry Boat Captain

Later, Ballance introduces the teachers to Rudy Austin, a tall and burly retired Hatteras ferry captain who now shuttles tourists to nearby Portsmouth Island.

Austin weaves stories about the remoteness of the village that is accessible only by boat, ferry or airplane.

“When I was a boy, they had only one nurse in the community,” he says. “I broke my shoulder at 3 o’clock in the afternoon. Since there was no X-ray machine on the island, a guy flew me in a two-seated plane to Buxton and then called the Navy base to take me to Oregon Inlet. From there, the Coast Guard took me through the inlet, and then I went by ambulance to Norfolk. By the time I got to the hospital it was 6 am.”

Austin has fond memories of belonging to a mounted Boy Scout troop that cared for Ocracoke’s wild ponies. “Back then, we did everything on horseback. We even took the horses camping. That changed when the National Park Service took over caring for the horses.

As a resident of the island for more than 58 years, Austin has seen many physical changes to the island.

To find out how much the island has eroded over the last 125 years, he and fisher Gene Ballance spent the last several years developing a series of maps comparing the changes from 1750 to 1999.

As Austin points to the north end on the map, he says, “it has been eroding at a steady rate of 10 feet a year. When I was a boy, the beaches were as flat as the highway. There were no dunes or grasses on the beaches. I used to see sea turtles crawling up and down the main road. When the Park Service planted grass, it did away with the natural replenishment process.

However, he was surprised to find that the rest of Ocracoke is not washing away.

“The south end isn’t eroding,” he says.

The north end has been the sacrificial lamb. If we allow the north end to wash away, the rest of the island will also wash away.”

The village is on the south end, but Austin also has strong ties to the north end. For many years, he was captain of the Hatteras ferry route. “If the north end goes out, we are ruined.”

Ocracoke Minister

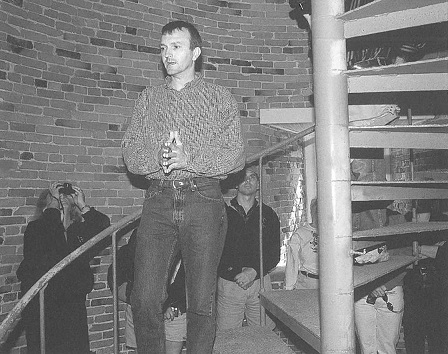

To get a glimpse inside a minister’s life in a tiny village, the teachers meet Rev. Keith Sikes at the Ocracoke Assembly of God Church — a white-framed building nestled among small cottages.

A tall, outspoken young man, Sikes is the church’s 37th minister. While standing in front of the teachers seated in wooden pews, he gives an overview of the church.

“The church is one of the few Assembly of God churches directly linked to the Azuza Street Revival in Los Angeles,” the birthplace of the Pentecostal revival movement in the United States.

“The front part of the building was constructed in 1941, and the back was given to the church by the Navy,” Sikes says.

“This building has gone through a lot,” he says. “It survived the hurricane of 1944 when one member saw the top turned over and taken down the street. The building flipped and touched a power line, which kept the whole building from going over.”

Sikes says it’s challenging ministering to a congregation of only 24 people.

“The people are unique,” he adds. “Since the Methodist minister and I are the only full-time ministers on the island, we are like community chaplains. We pastor everywhere we go. It is hard to even go to the Ocracoke Variety Store without pastoring. You have to leave the island to get away.”

At times, Sikes says the island’s remoteness is difficult for him, his wife and two young children who are home schooled.

“We have a love-hate relationship with the island,” he says. “My children’s involvement with other youngsters is limited.”

Despite the difficulties of living in a tiny village, Sikes has been touched by the residents’ compassion.

“The people are good and family-oriented,” he says. ‘They will quit their jobs to care for an elderly person. Mr. Clinton Gaskill who died recently didn’t want to be in a rest home. So the community made up a roster, and people took tums caring for him. This touched me.”

After a member dies, Sikes says a local representative takes the body by ferry to a funeral home on Hatteras Island. After the body is embalmed, it is brought back to the island church where the remains are often viewed.

“We usually don’t have a service for two to four days after someone dies,” says Sikes. “You have to wait for relatives to travel here.”

For many years, Ballance’s father served as the representative of the funeral home and transported bodies in an old gray station wagon across the ferry.

“I have seen my Dad go out all hours of the night,” he says. “If the ferry wasn’t running, he would sometimes park the station wagon with the body in our back yard.”

After visiting the church, Ballance leads the teachers down the street to the Ocracoke lighthouse, the island’s most prominent landmark. As the oldest lighthouse in North Carolina and the second oldest in the United States, it has guided mariners along the treacherous coast since 1823.

“The lighthouse is active and runs from dusk to dawn,” says Ballance. “It can be seen 13 miles from Ocracoke.” Inside the striking white tower, Ballance shows the five-foot thick brick walls and the steel, spiral staircase that leads to the top. “The top story is not centered. It is offset to allow for the exit of the lightkeeper.”

Local Author, Teacher

After a morning of viewing historical sights, Ballance and the teachers eat at a local restaurant. Then they trek down a pristine beach, which overlooks the Atlantic Ocean and is part of the Cape Hatteras National Seashore. Of the 5,535 acres on Ocracoke, only 775 acres in and around the village are outside of the seashore’s domain.

An avid naturalist, Ballance seems to know every dune, creek and plant on the beach. As waves crash against the white beach, he points out a dw1e that was reshaped by the N.C. Department of Transportation.

“The area was pushed down by Hurricane Floyd,” he adds. “The wind spread the sand across the highway.”

A small and energetic man, Ballance also stops and digs through the sand for mole crabs and then draws a map of the Outer Banks in the sand.

“This area is very alive,” he says. “You see mole crabs, and birds flying up and down the beach.”

As a first-time visitor to Ocracoke, Murphy teacher Ronda Phillips finds the beach “breathtaking.”

“I like Ocracoke because it is so relaxed and laid back,” she says. “You can leave behind the pressures of daily life.”

Ballance also leads the group across the highway to a maritime forest thriving with huge live oaks. At the beginning of the trail, he explains why an oak tree is shaped like a deer antler.

“This tree is on its last days,” he says. “It probably got bent during a hurricane and started growing the wrong way.”

As the trail snakes under a mass of trees, Ballance points out a marshy area covered with cattails.

Marshes are some of the most productive areas on earth. “Just offshore is where I used to go mulleting with two fishermen — Uriah and Sullivan. We would set the net out of a wooden skiff. Sometimes we would come close into shore and chase mullets onto the banks. It was a great adventure back then.”

Later, Ballance and the group hike down a path covered with pine straw to a huge live oak bent over like a piece of sculpture.

“If this area was not a national seashore, it would be filled with houses,” he says. “Some federal lands are being commercialized. That might be the quest for the future. It depends on the political structure. But I don’t think it will happen here.”

After a day-long trek around the quaint island, the teachers relax by listening to a local musician at Ocracoke School.

During a buffet dinner prepared by the school’s student government association, Martin Garrish, a bearded, middle-aged Ocracoke native, plays a variety of country, old-time and bluegrass tunes on the guitar.

“Music was important to my people,” says Garrish. “There was no TV. You would get off work and hear music in the community. I remember hearing the famous vaudeville banjo player Edgar Howard at my grandfather’s house.”

Garrish, who makes a living as a carpenter, began performing as a youngster in variety shows. Later, he played in a rock’n’roll band and at local bars. Now he performs in the summer at an outdoor stage.

“I am a self-taught musician,” he says. “I can’t read music.”

Many of Garrish’s songs are about the Outer Banks. While performing, you notice his distinct Ocracoke dialect or brogue. Some historians claim the dialect has traces of Elizabethan English.

Murphy teacher Phillips was so intrigued by the residents’ brogue that she plans to have her gifted students study it.

“Since I live in the mountains where there is also a dialect, the students can compare the two dialects,” she says. “I also will probably do something about the history of Ocracoke and am considering hooking up my students as pen pals with Ocracoke students. However, no study of Ocracoke can convey what I learned from meeting the local people. It is a beautiful place filled with remarkable people who touch your soul.”

Phillips hopes the course and correspondence will help her students understand Ocracoke’s remoteness.

“We feel isolated in Murphy but not as isolated as Ocracoke,” she adds. “They are up against some heavy odds. For example, home health care is limited there. I spoke to one man whose father needs physical therapy three times a week, but can only get someone to his home once a week. You have to really want to live on Ocracoke to deal with these obstacles.”

This article was published in the High Season 2000 issue of Coastwatch.

For contact information and reprint requests, visit ncseagrant.ncsu.edu/coastwatch/contact/.

- Categories: