PEOPLE AND PLACES: Discovering Down East on the Outer Banks National Scenic Byway

The beaches of the Outer Banks are legendary, but its roadways are steering into the spotlight. This summer, the Outer Banks National Scenic Byway is ready to guide visitors on an exploration of the culture and history of the North Carolina coast.

The byway’s southern range includes an area in Carteret County known as Down East, with expanses of marsh interrupted by small communities where fishing is a way of life and locals tell stories of generations past. This summer is the perfect opportunity to discover the sun-washed roads of this corner of North Carolina.

The byway is a natural fit for Down East. “We need a quality, education-based, heritage-based, resource-based visitor experience — and that is what the scenic byway program is grounded in,” says Karen Amspacher, Carteret County chair of the byway advisory committee.

The Outer Banks National Scenic Byway has been in the works for over a decade. In 2003, representatives from Dare, Hyde and Carteret counties began updating planning documents to request federal recognition for what was then a State Scenic Byway.

The representatives ultimately merged to create a regional advisory committee. The committee’s former chair, Mary Helen Goodloe-Murphy, still is impressed by the cooperation among the three county jurisdictions. “It’s a testament to folks really supporting the project,” she recalls.

The byway received federal status in 2009.

“There are only 150 nationally designated Scenic Byways, and the Outer Banks Scenic Byway is one of them,” Goodloe-Murphy says. “And that’s a big deal.” Other National Scenic Byways include Route 66 and the Las Vegas Strip.

From its northern terminus at Whalebone Junction in Dare County, the byway runs south along Hatteras Island. A ferry takes travelers to Ocracoke Island in Hyde County. The byway then skips over to Cedar Island in Carteret County via ferry. From there, it squiggles down the stretch of inner coastline known as Down East, ultimately reaching its southern-most point in the village of Bettie.

“Down East is a sailing term,” says Carteret County historian Connie Mason, explaining the unusual name. “It means that when you leave Beaufort, you sail downwind and east to go around Cape Lookout and the banks.”

In spring 2016, roadside signs — featuring iconic images of a lighthouse and a boat nestled in the dunes — were installed along the byway to guide drivers.

“I know for the people Down East, when the signs went up, people were very proud,” Amspacher says. “People were very proud that, at long last, they had been recognized for being important.”

Amspacher, along with cultural anthropologist Barbara Garrity-Blake, co-authored Living at the Water’s Edge: A Heritage Guide to the Outer Banks Byway. The book introduces readers to the varied communities along the byway.

SLOWING DOWN IN CEDAR ISLAND

Visitors arriving in Down East from the north begin at the Cedar Island ferry terminal on N.C. 12 — and quickly enter the Cedar Island National Wildlife Refuge. The refuge was created in 1964, but the road through its 14,595 acres feels timeless, surrounded by dense salt marsh outlined by distant stands of trees.

It’s well worth making a quick side trip from the byway to meet Kevin Keeler in the refuge office. As the sole U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service staff member at the refuge, Keeler welcomes the chance to share his knowledge with visitors. “If the white truck’s in the parking lot, I’m around,” Keeler says.

His office embodies a curious slice of American history. It was built in 1967 as a Navy tracking site known as Condor 3. “The premise behind this facility was, it stuck out so far east, they had a southern hemisphere shot with their radar dish,” Keeler explains. “It was a gut reflex to the Cuban Missile Crisis.”

The Navy left in 1970, but the 32-foot tower that formerly supported an enormous radar dish still stands across the street, physical evidence of the area’s history. It’s just down the road from a kiosk that includes a trail map, a code for a cellphone audio tour, and photos of the many birds that live in or pass through the property.

“The impetus to establish Cedar Island as a refuge was to maintain habitat for this species, a black rail,” Keeler explains. The number of black rails in the state and in the Cedar Island Refuge has declined dramatically in recent decades. Despite this, the refuge remains an important habitat.

In fact, the refuge provides a habitat for over 250 species of birds. That’s not hard to imagine on the trails, where songbirds trill over the rustle of marsh grass. The Cedar Island Refuge feels like a portal to not only Down East, but to the Outer Banks of old.

FROM PAST TO FUTURE

Of course, time will not stand still on the byway. “In 2020, connections to each other, this place, and our heritage will be strong,” notes its vision statement. Sustainable tourism can help realize that vision.

North Carolina Sea Grant Extension Director Jack Thigpen proposed a study that would enable the byway advisory committee to track the trail’s sustainability. The assessment was conducted in 2016 by Patricia Hooper, Alyssa Dykman and Kara Shervanick from Duke University’s Masters in Environmental Management program.

“Sustainable tourism promotes current usage without degrading or detracting from the cultural heritage, local environment, or economic well-being of the host community, while considering future economic, social, and environmental impacts,” the team explains in its report.

The students identified 10 sustainability indicators based on other studies and interviews with residents along the byway. The varied criteria included employment in travel and tourism, amount of impervious surface, and crime rates.

The report evaluated those metrics shortly before the roadside signs were posted. Thigpen explains that the baseline data will facilitate comparison in future assessments.

Residents’ passion for the Outer Banks was apparent in their interviews. “They really wanted this to be something that was more for local people,” Thigpen says. “They want something that celebrates the local culture and life and the fishing heritage.”

SHARING STORIES

As drivers leave Cedar Island, they will notice ample signs of that fishing heritage, from worn wooden docks alongside boat ramps to shops with faded signs advertising shrimp and crab cakes.

Family trees in places like Sea Level and Davis have deep roots Down East. “I’m hopeful that the byway can encourage people to tell stories about the villages and people in those villages,” Goodloe-Murphy says.

Communities already are sharing their stories with Mason, who is meeting with local representatives to create interpretive signs that will be placed along the byway in each village.

Mason begins by asking residents this question: If a stranger comes to your community, what do you want them to know? Their responses will be incorporated into the sign as text, photographs, a map featuring points of interest and a local recipe.

Down East villages selected a range of topics for their signs. Marshallberg profiles Capt. Fred Gillikin, who led “the first rescue in record of the newly formed U.S. Coast Guard” in 1915 off Cape Lookout, Mason explains.

Atlantic highlights its commitment to education, exemplified by a self-imposed tax to build a high school in the early 1900s. Brady Lewis, creator of the now-commonplace flared boat bow, is featured on Harkers Island. Many communities mention that farming has been a prominent local industry.

The interpretive signs will be installed in 2018, and they also will be available online. In the meantime, drivers can learn some history from the state’s historic markers, including ones on Cedar and Harkers islands.

“When people drive through the Down East communities, I’ve always said that it’s the cultural treasures that are hidden from view,” Mason says. “A lot of people will see older homes or crab pots in the yard, but they don’t know the true feeling and history of a place until they get to know the people. So I’ve been hoping that through these signs, they will get to know that it’s more than just a little community.”

HARKERS ISLAND HERITAGE

Near its southern extent, the byway splits. One direction swings west to Bettie, the byway’s southern terminus. The other branch leads to Harkers Island, bringing travelers past the bright blue exterior of Chadwick Brothers Bait and Tackle.

“It’s been a Chadwick family business since the 1940s,” explains owner Lillie Chadwick Miller. She’s seen a lot of changes in recent decades, with more visitors to Harkers Island taking the ferry to Cape Lookout or renting vacation houses.

Miller’s son Christopher rents the colorful kayaks stacked next to the shop. Miller recalls when a relative started a kayak rental business in the 1980s. “We all looked at each other and said, ‘Who’s gonna come down here and rent a kayak? What is he thinking?’” she recalls. Today, Down East Kayaks is going strong, renting to paddlers visiting from as far away as Japan and Norway.

Miller helped mobilize community involvement in the byway as a member of its advisory committee. She says that people who travel the byway “want that authentic, mostly quiet, natural visit.” Christopher agrees, noting that byway visitors enjoy seeing the historical buildings and graveyards Down East.

“I think that as the byway becomes more known throughout the country, more people will be wanting to come down here,” Lillie Miller says.

Christopher already has seen that kind of enthusiasm from visiting kayakers. “I had a crowd come in and say basically, we’re living their dream,” he says.

The byway continues to the Core Sound Waterfowl Museum and Heritage Center, which celebrates Down East’s history of fishing, hunting and boat building. Some of the waterfowl decoys on display are over a century old, their wooden bodies smooth from long-forgotten hunting trips.

Amspacher is the museum’s executive director, and she sees a tight connection between that position and her volunteer role on the byway advisory committee. “We are exactly what the byway is about, whether it’s cultural or natural history, or community involvement or responsible tourism,” she says. “We were the Down East voice in shaping what the byway’s become.”

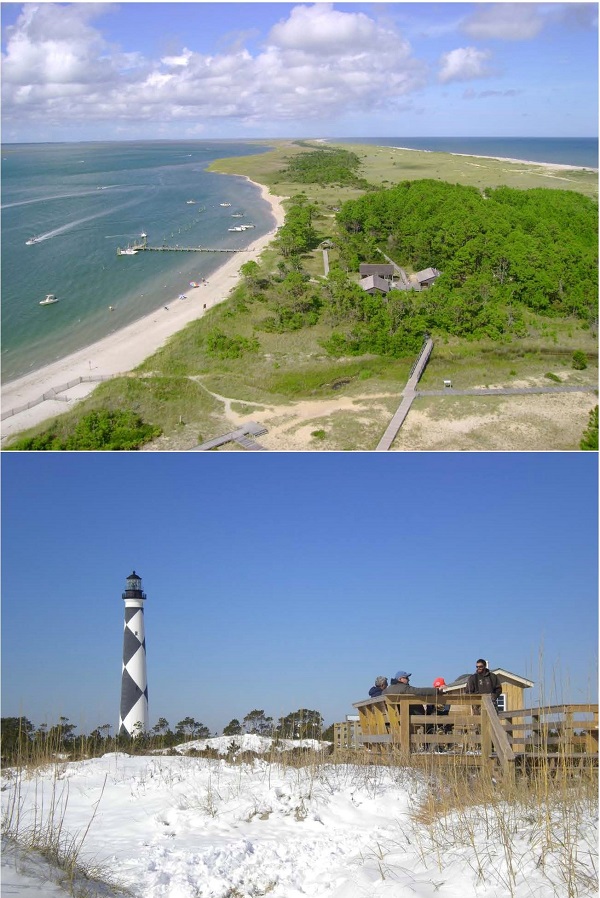

From the Cape Lookout National Seashore Visitors Center, located next door to the museum, byway drivers can hop a ferry to the cape. During the summer, they can climb its eponymous lighthouse to see Down East from a whole new perspective.

Goodloe-Murphy notes that summer isn’t the only time for a road trip. “The byway can be enjoyed very nicely in the spring and fall, so come ahead!” she says.

Sounds like an invitation to hit the road.

Find out more about locations along the Outer Banks National Scenic Byway at www.outerbanksbyway.com.

IF YOU GO

- Cedar Island Ferry Terminal: 3619 Cedar Island Road, Cedar Island, 877-629-4386.

- Cedar Island National Wildlife Refuge: 252-926-4021, www.fws.gov/refuge/cedar_island.

- Core Sound Waterfowl Museum and Heritage Center: 1785 Island Road, Harkers Island, 252-728-1500, www.coresound.com.

- Cape Lookout National Seashore Visitors Center: 1800 Island Road, Harkers Island, 252-728-2250, www.nps.gov/calo.

- Down East Kayaks: 1604 Harkers Island Road, Straits, 252-838-1336, www.downeastkayaks.com.

Read Living at the Water’s Edge: A Heritage Guide to the Outer Banks Byway by Barbara Garrity-Blake and Karen Amspacher for more about the communities along the byway. Also, look for an excerpt from the book in the Autumn 2017 issue of Coastwatch. The book is available from University of North Carolina Press.

This article was published in the Summer 2017 issue of Coastwatch.

For contact information and reprint requests, visit ncseagrant.ncsu.edu/coastwatch/contact/.