PEOPLE & PLACES: Goose Creek State Park: Home to Diverse Ecosystems

As the drumming of the pileated woodpecker echoes through a tea-colored swamp, Goose Creek State Park ranger Phoebe Wahab surveys the water for signs of wildlife.

Bending down on a wooden boardwalk overlooking a hardwood swamp, she spots a copperhead curled around a red maple.

‘The snake is usually in this spot when the sun comes out,” says Wahab. “Most of the time snakes also sun on logs over there. Sometimes there are so many snakes on the log that school kids think we put out props.”

Wahab, who seems to know every hiding place for snakes, walks a few feet on the other side of the boardwalk. Then she eyes another reptile — a redbelly water snake coiled in front of a thin tree.

“The boardwalk is a good place for people who are scared of snakes to see them and get comfortable with them,” she says. ”It is a great place to learn about a wetland environment.”

The hardwood swamp isn’t the only wetland at Goose Creek State Park, which stretches over 1,596 acres. Located near Washington, the park also is home to a cypress swamp and brackish marsh. A 375-acre brackish marsh along the Pamlico River has been designated a national natural landmark. It also is the longest segment of publicly-owned, undeveloped, low-salinity estuarine shoreline in the state.

”It is not a park where you just ride through,” says park superintendent Scott Kershner. “You need to get out and explore the seven miles of trails. A lot of animals make their home here in the wetlands because it is isolated.”

North Carolina Sea Grant acting extension director Jack Thigpen agrees.

‘The diverse ecosystem of Goose Creek makes it a great place to see many different types of plants and animals,” Thigpen adds.

Goose Creek also has an environmental education center. Interactive exhibits showcase the cypress and hardwood swamps and marsh. In the cypress swamp, you can hear sounds of wildlife — from a frog croaking to a screech owl hooting.

Nearby, specimens of animals peer from the wall and ceilings of the Discovery Room. A black bear has its mouth open like it is getting ready to take a bite out of a plant. A beaver is poised to slap the water with its tail.

“We look at taxidermy mounts as a teaching tool,” says Wahab. “It helps students and adults understand wetlands.”

From the center, you can walk down a trail to the hardwood swamp where many species of plants and trees flourish. On the edge of the swamp, towering loblolly pines line the path. Many have charred tree trunks from burning.

The park runs a controlled-burn program to slowly bring back the forest to its natural state, says Kershner. Frequent fires remove undesirable hardwood species that otherwise would crowd out desirable species, such as the long leaf pine. The burn program also restores the open long leaf pine savannas that existed prior to European settlement and subsequent extensive logging, he adds.

The park’s forest benefits in other ways — from disease control and improved accessibility to enhanced appearance and release of valuable nutrients back into the environment.

Burning also helps the park’s wildlife by reducing the amount of hazardous fuels from hurricane debris and leaf litter in the forest — which could build up and pose a serious wildfire threat, he says. In addition, Kershner says that wildlife such as deer, turkey, quail and dove benefit from fires, which increase yields of legumes and hardwood spouts, and provide open areas for feeding and travel.

Near the edge of the swamp, transition species — holly, yellow poplar, river cane and sweet bay — dominate the forest.

Throughout the swamp, many dead trees adorn the water. Some are stacked like a wall. Others look like pieces of sculpture.

”Dead trees can be useful for the environment,” says Kershner. “Animals such as wood ducks and flying squirrels nest in the cavities of the dead trees.”

Further down on the boardwalk, more wet-tolerant species, including black gum and green ash, provide a canopy for the swamp. Ferns and the dwarf palmetto palms create a tropical feeling. The swamp water also changes color from tea-colored to a mossy green.

To get a close-up of the brackish marsh, you have to drive or walk to another area of the park. The mile-long Flatty Creek Trail leads to the brackish marsh.

Along the way, you can see a variety of flora, including wax myrtles that beautify the forest. Loblolly pines also line the trail.

As you get to the marsh filled with tall grasses and rushes and a seashore mallow, an osprey screeches like a tea kettle. A butterfly flutters across the path, and several dragonflies create a blue reflection on the marsh.

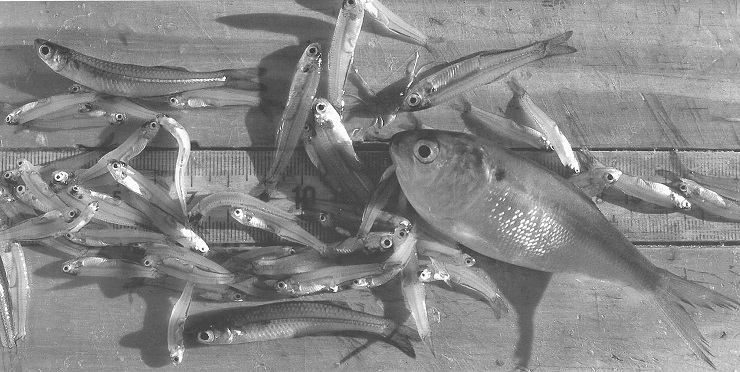

“The marsh is important because it is a nursery area for ducks and fish,” says Kershner. “It also filters out pollutants.”

The trail ends at an elevated observation deck that overlooks the Pamlico River and marsh.

“This is my favorite spot in the park,” says Kershner. “It is real peaceful. You can see the marsh and the Pamlico River.”

During the winter months, you can see a variety of birds on their migratory path. In late December, serious bird watchers come out for the Christmas bird count. Last year, bird watchers spotted a bald eagle.

‘”It is a big deal to see a bald eagle in the Christmas count,” says Kershner. “Usually they just see migratory bird fowl — duck, geese and swan.”

Goose Creek also is a haven for other birds, including barred owls and red-shouldered hawks and summer migrants like prothonotary warblers.

Along Goose Creek Trail, you can experience the mysterious feeling of the cypress swamp where large cypress trees crowd the muddy water. Sometimes, the swamp is not accessible because of large amounts of rain.

“The swamp is doing what it is supposed to,” says Kershner. “It is like the edge of a soup bowl and collects all the water around it.”

Large bald cypress trees dominate the swamp. Sweet and red bay, swamp cyrilla and sweet pepperbush grow below the cypress trees.

“The trees have a unique character because of their large knees and flared base at the buttress,” says Kershner.

Near the swamp entrance, a white-tailed deer leaps through the forest.

Visitors can fish from a beach on the Pamlico River. A trail runs from the road to the beach.

“This is one of the few public water accesses in Beaufort County,” he says.

Not too far from the beach area, a tiny cemetery commemorates 19th-century residents who are believed to have died from yellow fever, according to Kershner.

The gravestones are made of both wood and stone. Because the wooden markers have deteriorated, visitors can no longer read names of the dead.

“The people were brought across the Pamlico River and buried here to keep the disease from spreading to other people,” says Kershner.

As you walk down a trail to the main park road, you can see an open area where artificial nesting boxes have been inserted in trees to encourage nesting by the endangered red-cockaded woodpecker.

“It takes more than a year for a red-cockaded woodpecker to create a cavity,” says Kershner. “Active nesting colonies are located beyond the park.”

Along the park road, you can spot other wildlife, including snakes, frogs and turtles sunning in their wetland habitat.

“Goose Creek is a great place to discover the wonderful mysteries within wetlands,” says Kershner. And, he adds, exhibits at the Environmental Education Center help visitors interpret wetland areas and understand the importance of wetlands to wildlife — as well as to ourselves.

You can paddle the waters of Goose Creek State Park April 1 during Coastal Plain Waters 2001.

Goose Creek State Park is in Beaufort County on the north side of the Pamlico River. From Washington, follow U.S. 264 for 10 miles, then turn onto Hwy. 1334 (Camp Leach Road) for 2.5 miles to the park entrance. Park hours vary by season. For more information, call 252-923-2191 or visit the Web at www.ncparks.gov and follow the links to coastal parks and Goose Creek.

This article was published in the Winter 2001 issue of Coastwatch.

For contact information and reprint requests, visit ncseagrant.ncsu.edu/coastwatch/contact/.

- Categories: