Hurricane Fran: Memories and Lessons

When Hurricane Fran slammed onto Topsail Island in September 1996, it destroyed the Medlin family’s fishing pier, two restaurants and a motel.

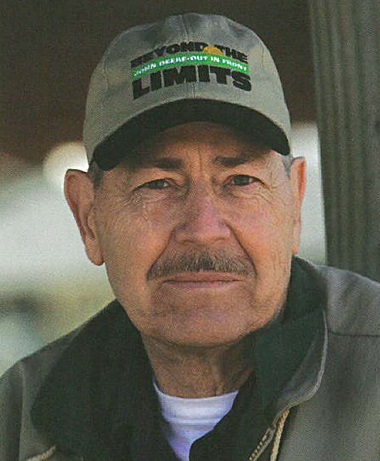

“It was the worst storm to hit the area since Hurricane Hazel,” says Doug Medlin, the owner of the Fishing Village in Surf City. “There was so much damage that we didn’t rebuild the facilities.”

Instead, Medlin tore down the old one-story building where the Fishing Village now stands and built a two-story structure that houses a tackle shop, clothing stores, a surf shop and a real estate office.

The toll of Fran’s fury was high for many others along North Carolina’s southern coast: More than $5 billion dollars in damage; miles of beach sand and dunes sucked from the shoreline; and emotional scars that will last a lifetime.

After a 30-year reprieve from major hurricanes, the people of coastal and eastern North Carolina were given a first-hand lesson in hurricane dynamics.

The Category 3 storm made landfall north of Bald Head Island on Sept. 5, 1996, and continued its path on Sept. 6 — only a few weeks after Hurricane Bertha hit Pender and Onslow counties. Fran’s course took it inland up the Cape Fear River, west of I-40 into the heart of the Triangle.

“On Topsail Island, there were homes that floated away,” says Pender County Sheriff Carson Smith, who was director of Pender County Emergency Management in 1996. “One house was sitting in the marsh between Topsail Beach and Hampstead.”

Although many homes and businesses were lost, the rebuilding began in the months after the storm. Now, almost 10 years after the storm, the coastal population has increased, as has the number of businesses.

In Pender County, there are close to 20,000 more people on the island, according to Eddie King, current director of Pender County Emergency Management. “After Fran, we decided to have another shelter available during emergencies. This year, we are considering a fourth shelter.”

Many other changes have occured along the North Carolina coast since Fran, including a new beach insurance plan for coastal homeowners.

What other lessons have researchers, government officials and residents learned from Fran? And how much have the beaches recovered?

BLOWING IN THE WIND

Beach dynamics are a complicated puzzle of interacting elements — winds, waves, currents, sand and geologic formations. The way these elements fit together determines how a beach responds during a hurricane, as well as how it recovers after a storm.

Wind transports fine grains of dry sand above the wet beach. If these grains are halted by vegetation or other obstructions, they pile up to build dunes.

Dunes act as reservoirs of sand that help to buffer nearby structures and landscape from the waves and surging waters during hurricanes and other major storms.

“Unfortunately, a myth has evolved that sand dunes are a cure for all types of erosion,” Spencer Rogers and David Nash explain in The Dune Book, a North Carolina Sea Grant publication.

“In the real-world, sand dunes are very poor protection from long-term erosion, inlet changes and even seasonal fluctuations in the beach,” the authors add.

When it comes to storms, the more sand between you and the ocean, the better, says Rogers, North Carolina Sea Grant’s coastal construction and erosion specialist. But for some beaches, sand was in short supply during the summer of 1996.

Southern coastal beaches — including the towns of Topsail Beach, Surf City, North Topsail Beach and Kure Beach — received a one-two punch with Bertha and Fran hitting close together.

In July, Bertha had eaten away the berm and took a bite out of the dunes. Large quantities of sand were moved offshore. Summer waves were starting to restore sand to the beach just as the powerful Fran moved in.

With a sparse supply of protective sand, Fran’s waves and surge quickly swept away the remaining dunes. In many cases, the water overwashed segments of the barrier islands from Bogue Banks south to Kure Beach. In some areas, 20 to 30 feet of beachfront were washed away.

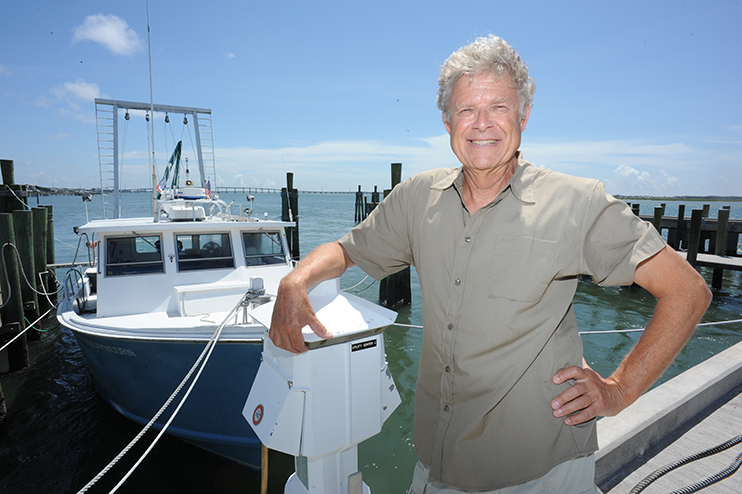

“It is difficult to measure the long-term effects of Fran, but it was very devastating to the beaches and infrastructure,” says North Carolina Sea Grant researcher Bill Cleary.

“Recovery is particularly difficult to measure on developed beaches where there is nourishment,” he adds. “Clearly, the majority of Topsail Island, particularly North Topsail, is worse off than before Fran.”

From the high-rise bridge to the tip of North Topsail, the dunes remain in bad shape, says Cleary, a University of North Carolina at Wilmington scientist. “There are a lot of new homes, but not a lot of dunes for storm protection,” he adds.

Surf City, in the middle of Topsail Island, has seen some recovery, Cleary says. “All the dunes were destroyed during Fran. Many have been rebuilt artificially.”

Of those areas in Hurricane Fran’s strike zone, Wrightsville and Carolina beaches fared best, according to Cleary. The damage at Wrightsville Beach was primarily overwash and erosion in the central section, from Johnny Mercer’s Pier to the Holiday Inn, he says.

SEEKING PROTECTION

Prior to the 1996 storms, both Carolina and Wrightsville beaches had received thousands of tons of sand in “nourishment” projects. Rogers says that the limited storm damage on those beaches emphasizes his point: More is better when it comes to sand and storm protection.

Tony Caudle, who was Wrightsville Beach town manager in 1996, agrees. “In some locations, the beach was devastated, but few structures were lost,” he says, adding that the worst damage was at the Holiday Inn, just north of the protected area of the beach nourishment project.

Because Wrightsville Beach fared so well during Fran, many beach communities began to see beach nourishment as extra protection from coastal storms, according to Walter Clark, North Carolina Sea Grant coastal communities and policy specialist.

But beach nourishment doesn’t come without high cost and controversy over environmental impacts.

In Emerald Isle, the average cost was $1.7 million per mile of sand replenishment for projects in 2003 and 2005, according to Town Manager Frank Rush. “There are many variables for beach renourishment, including how far away the sand source is,” Rush explains.

“Our beach nourishment project saved the day during Hurricane Ophelia. Are as with regular overwash and heavy damage came through the storm unscathed,” he adds.

Not all communities can afford nourishment projects — some opponents argue the investment may wash away in the next big storm.

North Topsail is sand-starved as the nearby ocean floor has a hard bottom that traps the sand in between the natural reefs. Beach nourishment there is more costly at about $12 to $15 a cubic yard, says Cleary. “This is two to three times what it would cost normally.”

Buildings most often are destroyed by waves and erosion that accompany storm-induced floods. Erosion can scour out footings, causing structures to collapse.

And the power of even small waves can pound piliings and damage homes. Research shows that a 1.5-foot or taller breaking wave can easily destroy a well-built house designed for 120-mph winds, Rogers says.

Wind gusts — which were clocked between 110 and 120 mph during Fran — did not directly damage many buildings, Rogers found during a post-storm assessment North Carolina’s building code requires that barrier island structures withstand winds of 130 to 140 mph.

Rather, most destruction was caused by storm surge that reached more than 12 feet above sea level — a height at or above the 100-year flood level. “The worst damage was caused by water levels, wave action and erosion,” Rogers says.

Current building practices include an open piling foundation, combined with a high first-floor elevation, so that waves can pass through unimpeded.

On Roger’s advice, in 1986 the N.C. Building Code Council had added new rules for erosion-prone areas, requiring pilings be sunk 5 feet below sea level or 16 feet below ground level.

Of the 205 Topsail Island structures built after the piling foundation standards were set in 1986, 200 buildings survived Fran and Bertha. But 180 oceanfront buildings built on shallower pilings were destroyed by erosion, Rogers notes. He suspects the five newer buildings lost were not in compliance with the 1986 code.

A post-Fran report from the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) urged better construction and inspection practices to ensure proper installation of the pilings in order to meet the state’s code requirements.

BUILDING CODE UPDATES

The N.C. Building Code Council makes updates every three years — and 2006 is one of those years.

“So there could be more code changes,” Rogers says.

Early this year, the council implemented rules requiring storm shutters for windows and doors on all new homes built within 1,500 feet of the ocean.

Several years ago, researchers from South Carolina and North Carolina Sea Grant, Clemson University and the Blue Sky Foundation designed a new type of plywood storm shutter for all homes. The shutters can be installed from the inside.

“Storm shutters may not be the highest priority for hurricane retrofitting,” says Rogers. “But as the wind-resistance of a building is improved, shutters become a top priority in high-wind zones. For some homes, threatening sources of debris may make shutters the first priority,” he says.

The new style of shutters must be prefitted.

Rogers emphasizes that no single technique will limit wind and water damage during storms. “Each house is different. What matters is finding the weakest components and looking for the most cost-effective priorities for each house.”

To minimize wind damage, Rogers advises homeowners to pay attention to connections — including using metal straps or hurricane clips rather than nails alone to secure the roof.

Garages also can be problem zones in high winds. “The garage is one of the weakest points in the house for lateral wind forces,” says Rogers. “The consequences of a door failure can be a greater structural threat than a loss of a window elsewhere in the house.”

His solution? Homeowners can install extra bracing and heavier tracks designed for high wind resistance.

INSURANCE OPTIONS

Since Fran, homeowners along the coast have better options for insurance coverage.

The N.C. General Assembly passed two separate laws to amend the N.C. Beach Plan, an independent, nongovernmental entity that provides insurance coverage for coastal properties when owners could not get traditional insurance.

Maximum limits are $1.5 million for residential property for windstorm and hail coverage along with $1.5 million for a homeowner dwelling for fire plus contents.

For commercial property, there is a $3 million limit per location to cover fire, windstorm and hail damage to the structure and contents, while an additional allowance of $300,000 could cover lost business income.

In either case, the maximum limits do not include land values.

In 1997, the legislature added a law to provide insurance coverage for windstorm and hail in coastal counties. In order to quality for the catastrophic coverage, the property owners must have additional property insurance written by licensed insurers.

“Hurricane Fran deepened the insurance crisis that led to extending coverage in the Beach Plan,” says Clark. “Cumulative concerns from Fran and previous storms led to a greater focus on insurance issues.”

In 2002, another law was passed that offered homeowners’ coverage for primary residences in the 18 coastal counties of eastern North Carolina. The plan previously offered only a fire and dwelling policy, which provided no liability or other needed coverage. The plan does not include coverage for rental property.

Insurance Commissioner Jim Long stresses that the legislation keeps costs reasonable, while offering broader protection. Long has the authority to approve rates in the Beach Plan, which are 15 percent higher than the rates in the traditional coastal markets. The N.C. Department of Insurance and the N.C. Rate Bureau set the rate in 2003.

“Residents of eastern North Carolina no longer have to struggle to find needed coverage at affordable prices,” Long says. “Finally, they can go to one agent to get the coverage they need — to protect their home from fire, wind, rain, liability and other needed coverage — the same protections a homeowner in the rest of the state expects.”

Flood coverage still is only available through the National Flood Insurance Program.

With the 2006 hurricane season upon us, are we better prepared for another big hurricane?

“Fran and the hurricanes of the 1990s reminded residents of the damage caused by large storms,” says Rogers.

But those memories may be fading.

Traditionally, barrier island homeowners have used open areas underneath piling-supported houses for parking and storage, allowing waves to pass under the house. But in the 10 years since Fran, some areas have allowed homeowners to put fully finished rooms on the ground level.

“It remains to be seen whether the demand for even larger coastal homes will overcome the memory of prior hurricane damage,” Rogers says.

“During Hurricane Isabel in 2001, some of the newest homes were more severely damaged than the classic beach homes that became common in the 1960s.”

To order a copy of The Dune Book, contact Sandra Harris, harriss@unity.ncsu.edu, 919/515-9101. Or send $5 to North Carolina Sea Grant, NCSU Box 8605, Raleigh, NC 27695.

To find out more about North Carolina’s Beach Plan, call 919/821-1299 or visit the Web: www.ncjua-nciua.org.

There also are numerous Web sites about coastal hazards, including:

- Sea Grant’s National HazNet: www.haznet.org

- Clemson University’s Wind Load Test Facility, www.clemson.edu/special/hugo/wind.htm

- North Carolina Sea Grant: www.ncseagrant.org

Follow the links to coastal hazards and outreach activities.

This article was published in the Early Summer 2006 issue of Coastwatch.

For contact information and reprint requests, visit ncseagrant.ncsu.edu/coastwatch/contact/.

- Categories: