Morehead City’s Changing Waterfront

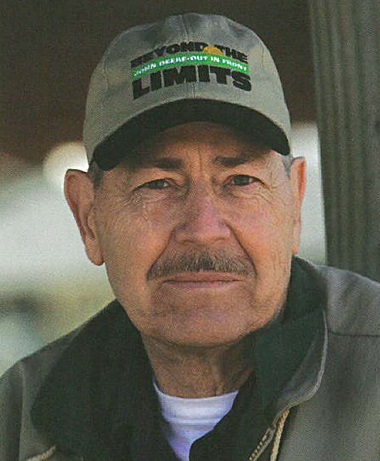

It’s a slow day along the Morehead City waterfront. Near the landmark Sanitary Fish Market & Restaurant, Capt. Gilbert Mathis washes down a large fishing boat after a rough night of snapper fishing,

“The weather changed on us,” he says. “The weather was supposed to be pretty good. We went to the Big Rock, and the current was running 2.2 knots. So we didn’t catch anything. That is a price you have to pay when you are fishing.”

Despite the uncertainties of weather and catch — not to mention rising fuel costs — Mathis has stayed in the business, while so many others moved on.

Not far from the commercial fishing boats, crews are cleaning and touching up charter fishing boats. The smell of salt water fills the air.

“It used to be all snapper boats where the Carolina Princess is now and over behind Ottis,” says Mathis. “There was a fleet of 20 or more snapper boats. Now it is down to seven or eight boats. There used to be two fish houses on the waterfront as well.”

The decline in commercial fishing fleets is just one example of how the Morehead City waterfront is changing. In both Morehead City and Wilmington — the state’s only designated “urban waterfronts” — redevelopment projects have included new restaurants and mixed-used buildings with condominiums on upper floors.

“Property values have gone way up in downtown Wilmington on the waterfront,” says Susi Hamilton, executive director of Wilmington Downtown.

“We have a strong residential component along the waterfront,” she adds, noting that waterfront condominiums are part of a state trend.

“A lot of people are looking at residential development on the Morehead waterfront,” says Doug Brady, who owns the former Ottis’ Fish Market, a waterfront landmark with turquoise siding.

“But you have to have enough going on to attract people to live there. It is a chicken and egg situation. If there is more retail businesses and activities, people might want to live there,” Brady says.

Waterfront parcels in smaller coastal communities also are being transformed for residential uses.

But not everyone is happy with the trend. Some people whose livelihoods depend on fishing, seafood sales and processing, and other traditional maritime businesses are voicing concerns about decreasing infrastructure and water access.

Coastal visitors also are seeing changes, as fewer marinas and fishing piers are available for the public.

“The public’s demand for seafood and access is growing, yet the opportunities are diminishing,” says Barbara Garrity-Blake, a Gloucester resident, anthropologist and a member of the N.C. Marine Fisheries Commission. “The access issue on waterfronts is a critical challenge that state officials need to address.”

Mathis, who refers to himself as a “farmer of the sea,” says he is living proof that with a few adaptations, fishing provides a viable living. He expanded his two-boat business into Runners Seafood, a retail and wholesale facility on N.C. 24 in Bogue Township.

“I did not put it on the waterfront, mind you, due to commercial property costs,” he adds.

NEW REGULATIONS

As waterfronts are attracting new uses, North Carolina has changed some regulations. For example, the state’s Coastal Resources Commission recently has modified coastal buffer restrictions for urban waterfronts.

Urban waterfront parcels must be within the corporate limits of a municipality in one of the state’s 20 coastal counties, and, in particular, within a central business district with urban services.

The rules now allow for urban waterfront development to take place over the water and within 30 feet of the water’s edge, as long as certain criteria are met, according to Doug Huggett, the N.C. Division of Coastal Management (DCM) major permit coordinator.

“Urban waterfronts have structures like fish houses over the water,” Huggett says.

“In most cases, the state doesn’t allow redevelopment of structures that extend over state-owned waters, but can allow such redevelopment along urban waterfronts.”

In Morehead City, Brady has a Coastal Area Management Act (CAMA) permit to construct a retail/residential building. “I don’t have an immediate timetable for this project,” he adds.

Brady bought the market in 1980. He closed the seafood business and restaurant in 2003, citing dramatic changes in the business from the early 1980s to the late 1990s.

“The wholesale seafood business is based on volume,” says Brady, a former Carteret County commissioner. “With more regulations and reductions in catch, it changed the dynamics of the business.”

Also, it became difficult to run the wholesale business in a public area. “There were many liability issues when running forklifts and parking trucks. The days are gone when you have boatbuilding and repairs, and fish house operations that are open to the public. Now, you have to put a fence around these businesses. You can’t afford to have people get hurt,” Brady says.

Shepard’s Point Boat Company — the only boatyard left on the Morehead City waterfront — added a fence because of insurance requirements, says manager Tommy Russell.

The boatyard, which caters to repair of sailboats and powerboats from across the East Coast, is a family business.

“This was my grandfather’s property,” says Russell of the property that is a stone’s throw from a retirement complex. “It is a great place for a boatyard.”

A PLACE IN HISTORY

Morehead City was bustling at the turn of the 20th century: The three-story Atlantic Hotel, one of the most famous hotels along the Atlantic Seaboard, overlooked the waterfront. Two fish houses, an ice and coal company, and several cottages also graced the area.

“In the early 1900s, it was supposedly the East Coast’s second busiest commercial fishing center, second only to Gloucester, Massachusetts,” according to Morehead City: A Walk Through Time by Jack Dudley.

During this era, many recreational anglers could be found in sharpies — sailing craft with a straight-plumbed bow and flat bottom, with no dead rise in the bow. Tourists also rode in the boats to the Royal-Chadwick Pavilion on the ocean side of Bogue Banks, according to Dudley. This was the beginning of the local charter boat fleet.

By 1912, a sea wall was constructed along the waterfront. And about the same time, Charles Seifrit of New Bern and D. B. Willis opened a Coca-Cola bottling plant where the Ottis’ site is today.

In 1933, the waterfront lost its biggest attraction when the grand Atlantic Hotel burned.

Five years later, Ted Garner Sr. and Tony Seamon opened their first restaurant, the Sanitary Fish Market — with 12 stools, a counter and a two-burner kerosene stove, according to Dudley’s book.

Food was cheaper then, but wages were low as well.

“I started working for 30 cents an hour,” says manager John Tunnell, who started at the business in 1944. “Back then you had to put the menu on the wall. The highest meal was a shore dinner for $1.50. You could order shrimp for 60 cents.”

In 1941, Headen Ballou, who became known as Capt. Bill, converted a fish house into the Waterfront Cafe and Fish Market. Eater, the restaurant was renamed Captain Bill’s Waterfront Restaurant.

Mullet boats would tie up nearby. “Big fish boats would unload at the fish houses on the waterfront,” says Tunnell, who is also a photo-historian.

“For-hire” boats still are found on the waterfront — and their numbers are increasing. Woo-Woo Harker has run the Carolina Princess out of Morehead docks for more than 25 years.

“I am now on my third head boat,” says Harker, whose face lights up when discussing his business.

“The boats have become more modern, sleeker and faster.”

Head boats typically carry larger crowds, while charter boats take out smaller groups.

“Now, there are a lot of people doing charter fishing on a part-time basis on the weekends,” says Marker, whose family ran “party boats” out of Harkers Island.

“Boats cost so much now that you have to want to do it. It is hard to make investment back from running fishing parties. You can’t get a 50-foot custom boat built for less than $500,000 to $700,000. To take out six people, it costs $1,400 a day.”

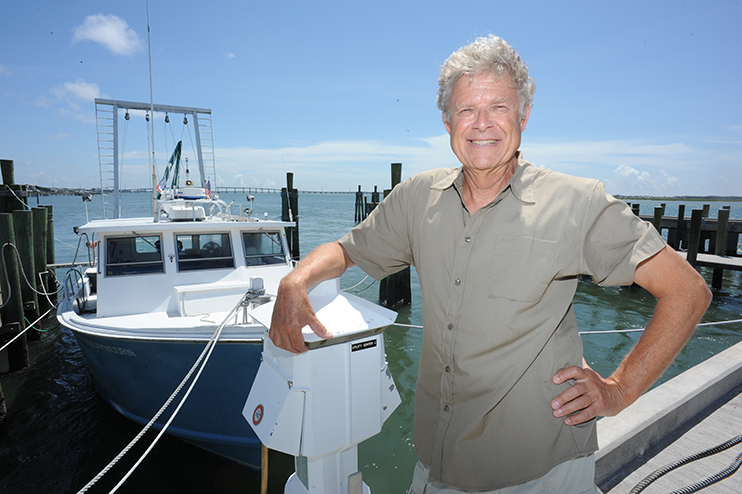

The Continental Shelf, which docks at the downtown waterfront, serves large fishing parties on a regular basis. “My family has been on the waterfront for more than 60 years,” says Capt. Bill Davis, the boat’s owner.

“My granddaddy was Capt. Stacy, and he started taking fishing trips out here. My daddy and his brother owned the first Capt. Stacy,” he adds. But now the larger Capt. Stacy Fishing Center operates off the Atlantic Beach Causeway.

Reminders remain of bygone days when colorful fish captains — including Capt. Ottis Purifoy — spent hours greeting tourists and fishermen. But times are changing.

“We just lost Capt. Ace Harris,” Tunnell says, “He was 89 and used to tie up here near the Gulf Dock that has been here for years.”

The Dolphin I, which is docked near the Olympus Dive Shop, also offers a piece of history. ‘This is one of the oldest wooden fishing boats left on the Morehead waterfront,” Tunnell explains.

“There aren’t many wooden boats built now. It is still maintained by Capt. George Bedforth, who is in his 80s,” he adds. “Capt. George caught some of the first blue marlin brought into Morehead City.”

WATERFRONT ATTRACTION

In addition to charter boats, the waterfront is home to the Diamond City tour boat and a variety of old and new businesses. Near the bridge to Beaufort, condominiums are being remodeled. Nearby are some boat slips and the headquarters of the Big Rock Blue Marlin Tournament, which started on the waterfront 47 years ago.

On a recent day, Tunnell gives a tour of the Sanitary Fish Market, a large restaurant known for its fresh fish, hush puppies and picture window that provide a waterside view.

Faces of famous North Carolina politicians and celebrities peer from the wood panel wall, including governors such as Kerr Scott and Terry Sanford, who also served in the U.S. Senate.

“Every customer is famous,” Tunnell says of the photos. “We have fed Ted Williams, Rocky Marciano, Robert L. Ripley, Ray Bolger, Skip Henderson, Tipper Gore and every governor since Clyde Hoey and Mel Broughton.”

Next door, the Key West Seafood Company — which serves South Florida seafood specialties — extends over the water near a dock with commercial fishing boats. Across the street, the old Ice House now is a restaurant, and there are a number of shops, including Dee Gee’s Gifts and Books. In the next block, Captain Bill’s, which is known for its conch chowder and seafood, extends out over the water.

“There have been a lot of changes on the waterfront since I came here 25 years ago,” says John Poag, owner of Captain Bill’s. “This place used to be a summer resort and open only during the summer season. Now, my restaurant is open year-round.”

The look of the waterfront also has changed. During the 1980s, the town of Morehead City obtained a Community Development Block grant to improve the appearance of the waterfront area.

Subsequent grants, private investment and town monies have maintained a “forward movement” such that the town now has a new sea wall, underground utilities, brick paved walkways with planters along the waterfront and new docks, according to the Downtown Morehead City Revitalization Association Web site.

Recently, the revitalization group applied for a federal grant to build public docks near the Jaycee Park. “There will be 10 boat slips available for the public,” says Joanne Alpiser, the association director.

The diversity of the area draws artists, restaurants and businesses, she says. At the same time, the waterfront offers a sense of history.

And folks love to go to docks late in the day to watch the catch as it is brought in, she says. “This is a Morehead City ritual at sunset.”

CHANGING WATERFRONTS FORUM IN NEW BERN JUNE 5

North Carolina Sea Grant will host “North Carolina’s Changing Waterfronts: Coastal Access and Traditional Uses,” a June 5 forum at the New Bern Riverfront Convention Center.

“North Carolina is experiencing a loss in the diversity of uses along its coastal shoreline,” says Walter Clark, North Carolina Sea Grant coastal law and policy specialist.

“Many of the state’s traditional uses such as public marinas, commercial fishing facilities and fish houses are being replaced by residential uses, as more people vie for waterfront property,” he adds.

The changes in coastal waterfronts has drawn the attention of the state’s Joint Legislative Commission on Seafood and Aquaculture, which has asked Sea Grant to help develop a proposal to create a study commission to look at the issues.

During the June 5 forum, participants will explore potential options for landowners and communities who want to preserve the diversity of our shorelines, Clark says.

The day-long program also will include sessions on how and why waterfronts are changing, including cultural and economic factors; and innovative ways that other states are dealing with similar issues.

Registration is $20, and includes all breaks, lunch and conference materials. A draft agenda and registration form are available online at www.ncseagrant.org/waterfronts. For more information, call 919/515-2454.

This article was published in the Early Summer 2006 issue of Coastwatch.

For contact information and reprint requests, visit ncseagrant.ncsu.edu/coastwatch/contact/.

- Categories: