Native Plant Species: The Solution

To paraphrase a popular saying: Neither torrential rain nor the heat of day can dampen the enthusiasm of native plant lovers as they make their appointed rounds in pursuit of their passion.

On a recent visit to Airlie Gardens in Wilmington, a soft drizzle turns into a drenching downpour as Gary Paynter and Lara Berkley climb aboard an open golf cart for an up-close look at native plants that abound along the garden’s nature trail. The women, members of the Southeast Chapter of the N.C. Native Plant Society, seem undaunted by the worsening weather.

Matthew Collogan, environmental education director for Airlie Gardens, navigates the narrow path, identifying the species of tree and shrub branches that intrude into the passenger space.

Berkley, her hair dripping wet, laughs good-naturedly, saying, “This is the kind of drama all nature lovers thrive on. It just makes us more enthusiastic.”

Collogan stops now and again, hopping out to call attention to a plant specimen half-hidden behind a tree or another shrub. His litany of native trees, shrubs and vines goes on — passion flower vine, beauty berry, smilax, red bud, Virginia sweet spire, red cedar, buck eye, sassafras, longleaf pine, southern magnolia.

And while he’s at it, Collogan points out the bird or butterfly associated with a particular plant species.

“It’s a natural connection — and why so many of us in the Native Plant Society also are members of Audubon North Carolina,” Paynter says.

Gardening is not just about native plant life, the women point out. It’s part of a much larger biological picture that includes insects, plants, soil and water. Native plants support beneficial native insect populations. Take them out, and it leaves a hole in the ecosystem that is an opening non-native, destructive insects fill.

Home gardeners usually strive for pest-free landscapes, notes Berkley, a professional landscape designer. “But the irony is that where there are no native plants and insects, there are fewer birds,” she says. She urges clients to choose nature’s aesthetic over manipulated “magazine” aesthetics that may compromise nature’s balance.

Getting back to nature’s aesthetic is a continuing goal for Paynter, whose move to Wilmington several years ago meant returning to her family home place on Hewlett Creek. She still is dislodging invasive plants and restoring the property to the native habitat and woods she knew as a child.

SPECIAL MEETING PLACES

Native Plant Society chapters across the state advocate the use of native plants in the landscape and opt for “meetings” that take members for walks through special places and gardens.

One hot humid afternoon, society member Jack Spruill enthusiastically invites visitors to tour the grounds of his home on a Hampstead tidal marsh. When he and his wife Jenny moved here nearly a decade ago, the top of his “to-do list” was returning the property to nature. Previous owners cultivated a lawn down to the water’s edge and landscaped with typical border beds, roses and assorted non-native plants.

He says he was astounded when the man advised him to wait till low tide to mow the lawn below the tide line — and to rinse off the mower to prevent salt water from mucking up the motor.

Instead, Spruill allowed the lovely marsh grass to pull back into the “lawn” and planted a row of wax myrtles and marsh elder just above the high-tide line. “I let nature take its course,” he says. “Besides, it’s much better for water quality.”

He uses a chain saw and ax to eliminate invasive and non-native plants and is filling in the spaces with indigenous plant material. “It’s a combination of loving woods and swamp — and making a statement against what I call corner-to-corner lot clearing by developers,” he says. In time, his side lot will be shaded with canopy trees he has planted: oak, ash, hickory, red and white cedar, southern magnolia, bald and pond cypress, elm and persimmon.

For the understory, he has wax myrtle, ink berry, sumac, red bay and sweet bay magnolia. The N.C. Native Plant Society recently recognized Spruill for “preserving, enhancing, conserving and protecting our environment.”

The payoff is greater than a framed certificate. Developing a native plant habitat is increasing the number of visitors to his “preserve.” Painted buntings, yellow ruffled warblers and myriad other birds enjoy the fruits of his labor, Spruill says.

RARE AND BEAUTIFUL

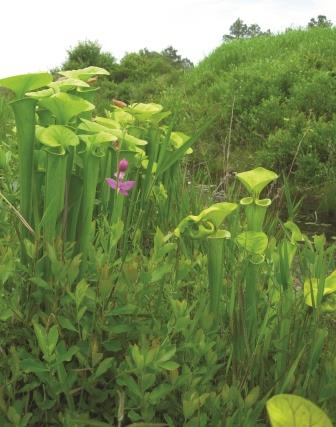

Many say it’s just hard to improve on Mother Nature’s design. That’s the case for The Green Swamp — a 13,000-acre preserve

in Brunswick County owned and managed by The Nature Conservancy. The preserve contains spectacular longleaf pine savannas that host diverse populations of rare plants.

With so much biodiversity to absorb, members of the visiting G. Gilbert Pearson Chapter of the Audubon Society don’t seem to notice that the intermittent rains had turned the preserve into a sauna. After all, there are 19 orchid species and 14 carnivorous plant species for them to discover at a time of year that many are blooming. And, they are not disappointed. The day’s sightings include Venus fly trap, pitcher plants, sun dew, wild iris, and myriad orchids.

Tom Harville, president of the N.C. Native Plant Society, and David McAdoo, the society’s orchid specialist, tell the Greensboro visitors that habitat loss and poachers are taking their toll on populations of the rare plants — found only in about a 75-mile radius of Wilmington.

GROWING A SOLUTION

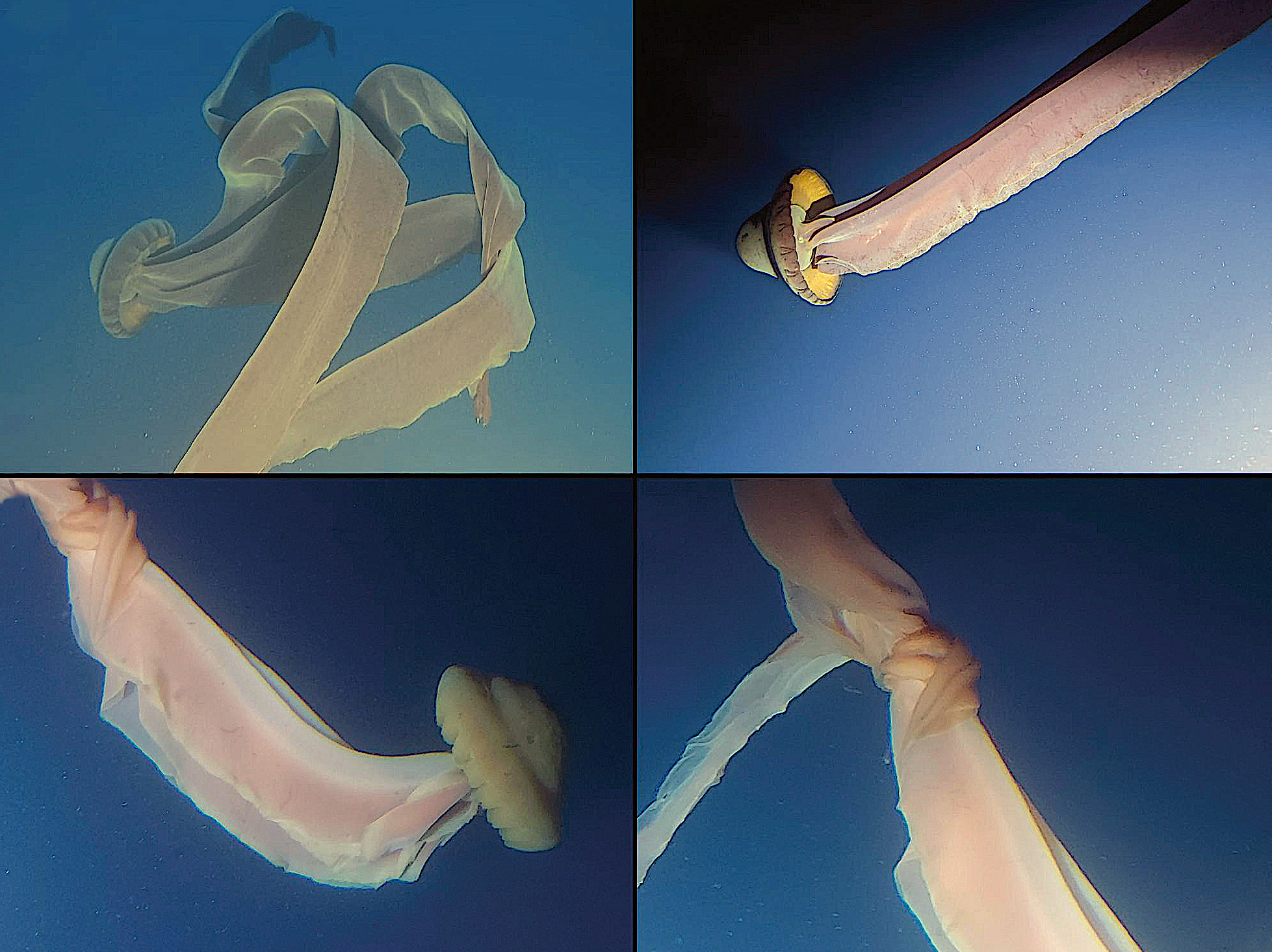

At Southeastern Community College (SCC) in Whiteville, Rebecca Westbrooks’ environmental and technology students are growing a solution to the problem of shrinking populations of Venus fly traps and pitcher plants.

With grants from the National Science Foundation, the Golden LEAF Foundation and the N.C. Community College BioNetwork, Westbrooks developed a state-of-the-art lab where students use tissue culture technology to propagate the carnivorous plants. Cells from one plant can create thousands of seedlings in test tubes in the grow lab, she explains. Plants are transferred from the lab to planting flats in a nearby greenhouse.

The N.C. Zoological Park purchases plants from the project and proceeds are returned to the program. “I call it paying it forward,” Westbrooks says. “We are reinvesting in our program to prepare more students for cutting-edge agribusiness jobs.”

The SCC rare plant success story could become a model for a broader application of tissue culture propagation — from organic food crops to sought-after native landscape plants. Westbrooks envisions biotech-based niche markets that will help generate a sunnier economic climate for rural Columbus County. — P.S.

WHY GO NATIVE?

Landscaping with native plants gives property owners the opportunity to support, in the most

fundamental way, the natural resources and ecosystems that are unique to North Carolina, explains Gloria Putnam, North Carolina Sea Grant’s water quality planning specialist. “Learning the roles specific native plants play and seeing them firsthand also allows us to understand and connect to the land in a way that gardening with non-native species rarely does,” she notes.

And it doesn’t have to be all or nothing in terms of using native plants. “You can start by slowly replacing older or diseased non-native plants, or reducing your lawn size a little at a time,” she suggests.

“But you might soon decide to make significant changes if you see that you are spending much less time and money on watering, fertilizing and maintenance.” The N.C. Native Plant Society promotes the use of natives in landscaping to provide food and shelter for native wildlife.

- Native plants in landscaping help sustain native butterflies, beneficial insects, birds, mammals, reptiles and other species.

- Beech, oak and hickory trees provide nesting habitat and important nuts and acorns for a variety of wildlife. In the winter, evergreen trees, such as the American holly, provide important shelter and food.

- Spring migrating and nesting birds rely on the insects in our forests to give them the energy to travel long distances and raise their young. Fall migrating birds depend on high-energy fruits from flowering dogwood, spicebush and Virginia Creeper.

The society notes one of the top benefits of “going native” is sustainability. While native plants create a “sense of place,” their use also increases the chances for a successful gardening experience because native plants have adapted to withstand regional soils, pests and weather extremes.

For information about native plant species and plant availability, visit the following websites:

- The N.C. Native Plant Society, www.ncwildflower.org

- The N.C. Botanical Garden, ncbg.unc.edu

- N.C Cooperative Extension and the N.C. Division of Forest Resources, www.ncsu.edu/goingnative.

This article was published in the Autumn 2010 issue of Coastwatch.

For contact information and reprint requests, visit ncseagrant.ncsu.edu/coastwatch/contact/.

- Categories: