Listening to the Sea

This article was published in the Summer 2010 issue of Coastwatch.

To many of us, “spiny dogfish” are meaningless words. Some of you might know it’s a small species of shark, while others know that the species is found worldwide and eaten by Europeans as “rock salmon” or used in fish and chips.

But to commercial fishermen along North Carolina’s Outer Banks, spiny dogfish have been a reliable, highly abundant fishery during the normally harsh winter months when few other species are accessible. Yet federal managers disagree, predicting sharp declines for spiny dogfish populations in coming years and issuing limited catch quotas for the fishery.

So for East Carolina University doctoral student Jennifer Cudney, “spiny dogfish” means an important research question. She’s listening closely to what the fishermen are saying and wants to know how science can clarify this heated debate.

That science also involves listening to the Outer Banks waters — listening for dogfish.

PRACTICAL APPLICATIONS

Cudney is studying under Roger Rulifson at East Carolina University. Rulifson is a frequent collaborator on N.C. Fishery Resource Grant (FRG) projects, which often bring seasoned watermen and university researchers together to examine fisheries biology and management issues. The FRG program is funded by the N.C. General Assembly and administered by North Carolina Sea Grant.

Rulifson has investigated the spiny dogfish issue for more than a decade, working with fishermen Dewey Hemilright and Chris Hickman over the years to track dogfish populations in North Carolina waters (see Coastwatch High Season 2007). They work together with respect and rapport, and it’s what attracted Cudney to study with Rulifson.

“I feel like Dr. Rulifson takes a very practical approach to the research,” Cudney says. “I think that [scientists] don’t spend enough time translating research to practical applications… this was a chance to work with a lot of commercial fishermen and really figure out a problem that was bothering them for a really longtime.”

Cudney is from Ohio, where the only sharks around are on the “Shark Week” television documentaries she watched as a little girl. Her grandparents took her fishing on Lake Erie for perch and walleye, and from those many outings, Cudney developed a love for coastal science.

But it was a college field course in coastal Mexico that opened her eyes to the realities of studying and managing marine resources.

Cudney studied the sea turtle fishery in Puerto San Carlos, a small fishing village where turtles are roasted and eaten during celebrations like Easter and Mother’s Day.

That served as a wakeup call, the notion that marine organisms can have historical, cultural or economic significance to a community. ‘There are people that are actually making a living,” Cudney realized. “It’s not just a big cuddly world where [everyone] can appreciate turtles as charismatic megafauna.”

Cudney particularly enjoyed working and talking with the local commercial fishermen. “I loved the fact that I was doing something that could help them and also learn something that could help the resource. So that was really the ‘Ah — this is what I really want to do!'”

MARATHON MIGRATIONS AND LISTENING FENCES

Cudney is getting her wish. The spiny dogfish fishery in North Carolina is under much contention. Based on their annual trawling studies from New England down to Cape Hatteras — from which commercial catch quotas are based — federal managers say that there aren’t enough breeding females in North Carolina waters to maintain the population.

The local fishing community believes otherwise. They say that dogfish are bountiful just south of Cape Hatteras during the winter season, when dogfish migrate down from the northern waters of New England and Canada. And they’ve seen plenty of mature female dogfish in their catches and would like to harvest more of them.

Clearly, there are some unanswered questions. Where are the dogfish congregating around Hatteras, and how actively are they moving around within the area? Is it possible that the federal population studies are trawling in areas where dogfish don’t congregate and are collecting inaccurate estimates? Are there actually more mature dogfish than sampling suggests, meaning that quotas can be raised?

If we could only ask the dogfish.

But Cudney and Rulifson have figured out the next best way to investigate these questions. They’ve teamed with fishermen Hemilright and Hickman on a suite of FRG projects to study the movement of dogfish off of the Outer Banks. Over the last two years, they have captured and released 93 mature spiny dogfish with acoustic tags surgically implanted in their bellies.

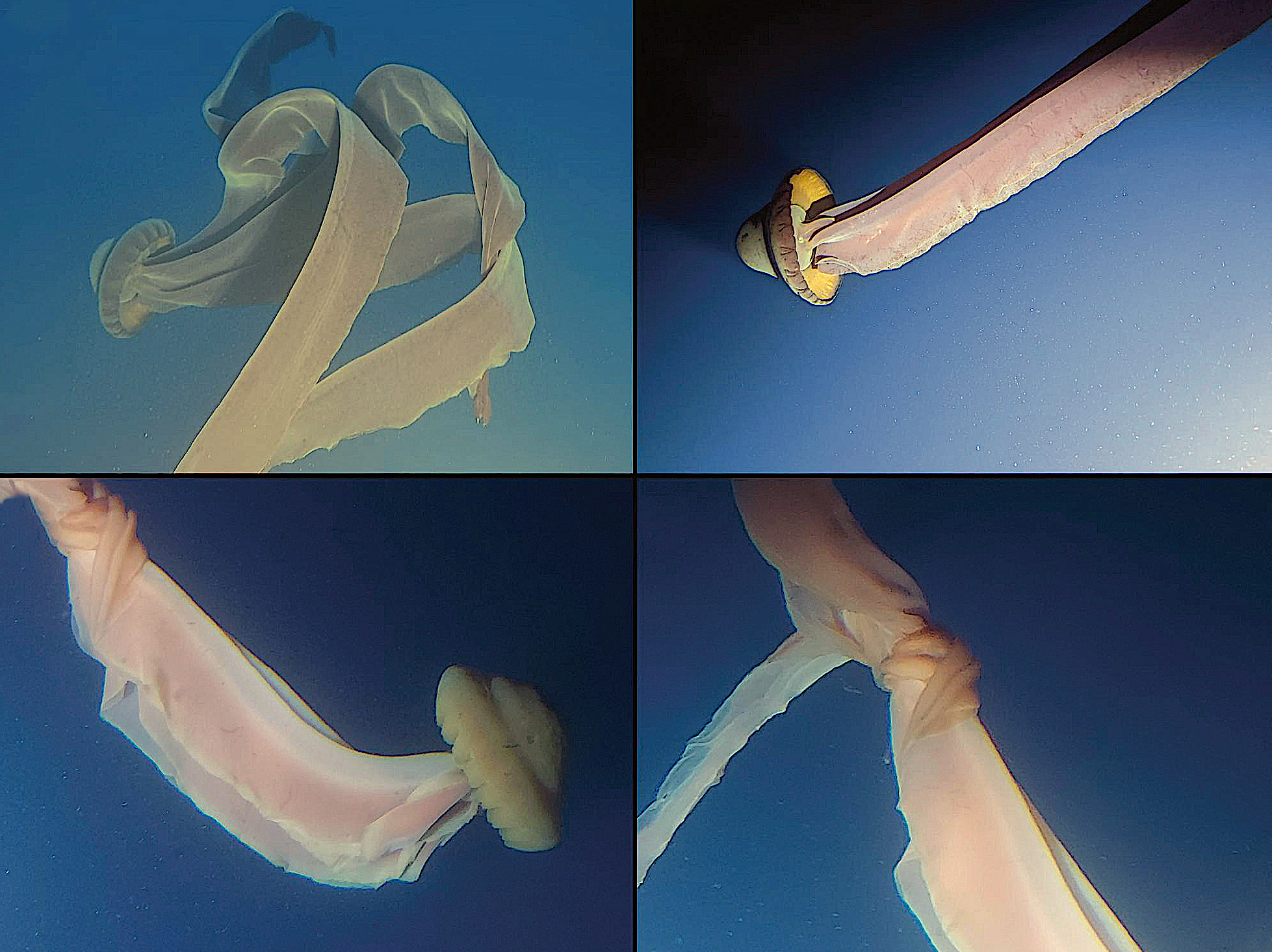

These acoustic tags literally let the dogfish talk back to the researchers, so that each animal’s movements can be tracked. These tags give off sound signals that can be detected by underwater instruments, alerting the researchers to the location of each dogfish. One instrument called the VFIN — which looks like a miniature fluorescent spaceship — can be trolled behind a boat. Anytime the VFIN passes by a tagged dogfish, a boat computer will log that fish’s location and swimming direction, and Cudney will hear a chirp on her headphones.

The team has also set up a “listening fence” north of Hatteras Inlet. This fence consists of a linear trail of 10 acoustic receivers stretching perpendicularly out to sea, anchored to the seabed and spaced over 10 miles. When a tagged dogfish crosses this listening fence, the nearest receiver will log that particular tag in its memory. Other probes along the fence are recording water temperature and chemistry, as well as ocean current speed and direction.

Eventually, the team hopes to gather enough movement data to discover how dogfish move and congregate around Cape Hatteras, and whether those movement patterns are linked to changes in currents, temperature, time of day, or other ecological factors. Understanding these patterns will help fishery managers improve their sampling surveys and population estimates, and in turn inform future management decisions.

LOCAL ECOLOGICAL KNOWLEDGE

Although the listening fence can be deployed and left alone to work automatically, the active tracking portion of the study is more time-intensive. Hickman, Hemilright and Cudney must troll the VFIN detector unit up and down the Hatteras waters, hoping to pick up a chirp from one of the tagged dogfish.

“It’s just like an eight-hour work day,” Cudney says of her arduous listening sessions. “A lot of days we’re just zero hits… but we’re still recording useful data.”

It might sound tedious, but to Cudney, every trip is a valuable experience. Riding shotgun all day alongside experienced mariners like Hemilright and Hickman offers her lessons that no classroom can offer.

“We talk about politics, dogfish, bull sharks, how the tilefish are running… pretty much everything,” Cudney says.

It’s what she calls “local ecological knowledge” — the expertise and insights about an ecosystem gained by the people who live in it and off of it. In this case, the fishermen who ply the Outer Banks every day, who observe the moods of her seas and the movement of the fish schools season after season. The key to Cudney and Rulifson’s research progress has always been to listen to those fishermen, and to combine that local ecological knowledge with scientific methods to explore management issues affecting that ecosystem and its communities.

So Cudney listens on, to the dogfish and to the fishermen.

“I’m learning a lot from them.”

To learn more about the ECU spiny dogfish research, or to report tagged dogfish and lost research equipment, visit www.spinydogfish.org.

View the poster that explains how the ECU listening fence detects migrating dogfish.

- Categories: