Storm Practices: Lessons Learned from Hurricane Irene

Even Ann Keyes learned a lesson from Hurricane Irene about the importance of reliable communications and being prepared for the worst.

“Have a Plan C for your Plan B,” advises the Washington County emergency management director who has 25 years of experience under her belt. During the storm, Keyes’ Internet connection went down and her pre-tested air cards — devices that give users mobile Internet access using their cellular data service — did not work.

“I relied on good relationships with my partners, so that I could get into the store and get new cards,” she recalls.

Keyes shared her Irene experiences with more than 150 other emergency managers, meteorologists, public information officers, emergency responders and university researchers at the third annual N.C. Division of Emergency Management-East Carolina University Hurricane workshop, co-sponsored by North Carolina Sea Grant. The May event highlighted the role of emergency communications and the lessons learned from Hurricane Irene in 2011.

The hurricane taught North Carolina emergency managers and their communities the importance of accurate and detailed communications before, during and after the storm. They depend upon early forecasting from the National Weather Service, or NWS, and clear communications to residents and visitors to make sure that people are able to evacuate vulnerable areas.

The National Hurricane Center found that effective communications are just as important as the development of accurate weather models in forecasting hurricanes. Improved strategies include using maps and graphics, and collaborating closely with news media to inform the public.

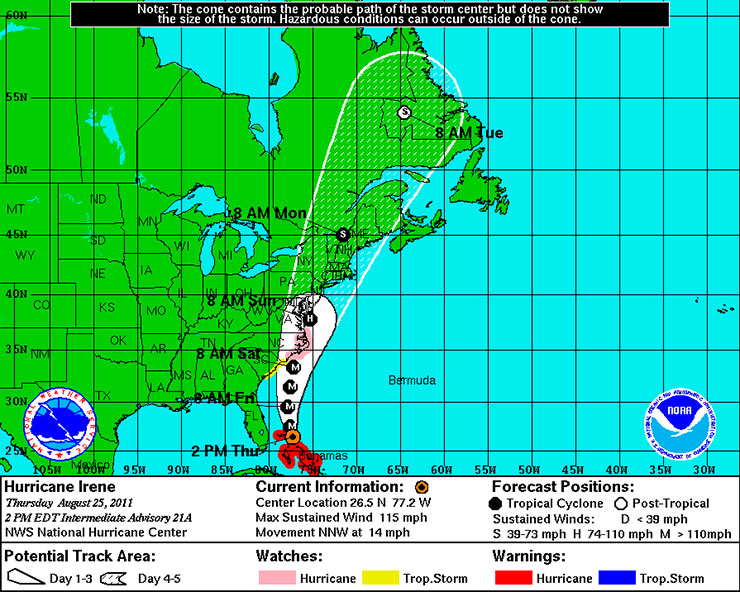

Many people had not expected that Irene, a Category 1 storm when it made landfall, would do so much damage. During the storm, areas of Hyde County, which includes Ocracoke Island, experienced a 7-foot storm surge, major flooding and sustained high winds for hours. Eighteen homes were destroyed, and 803 residences and businesses were affected.

However, the hardest part has been rebuilding. “Most people did not expect the recovery process to take as long as it did. It is like switching from a sprint to an endurance race,” says Justin Gibbs, Hyde County’s director of emergency services, who also attended the workshop.

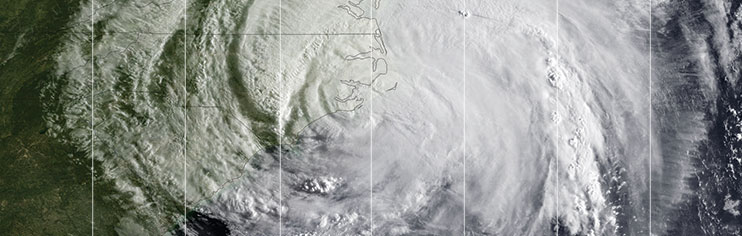

FORECASTING IRENE

The impacts of Hurricane Irene, especially in areas surrounding the Pamlico Sound, surprised many people. Sustained high winds and major flooding from storm surge caused greater damage than most people anticipated. NWS forecasts were accurate but people still were caught off guard.

“People just did not think that the impacts from a Category 1 would have been so substantial,” says John Cole, warning meteorologist with the NWS in Newport/Morehead City.

Although meteorologists correctly forecasted the track and rainfall amounts for the hurricane, people reported that they had no idea that the flooding problems would be so severe. Was this because the experts or the news media were not doing a good job at conveying potential risk? Or were people overly optimistic that they would not be personally affected by severe storms?

To understand the public perception of the threats posed by Hurricane Irene and find out how people responded to the weather forecasts, the NWS held public meetings in some of the communities hardest hit by the storm. At December meetings in Dare, Pamlico and Beaufort counties, participants were surveyed about their experiences and perceptions.

In addition, Rich Bandy, lead meteorologist at the NWS Newport/Morehead City office, presented comparisons of the forecasts for wind, inland flooding and storm surge with observations during and after the storm.

Meteorologists forecasted a low threat of tornadoes. However, there were three confirmed tornadoes in the state. The strongest, near Columbia, had maximum winds of 130 mph and caused severe local damage.

Wind impacts were projected to be extreme, with possible sustained winds of 115 mph for much of the coastal area. In actuality, “there were gusts of 90 to 100 mph in the corridor where the eye made landfall,” Bandy notes.

In comparing the forecast of inland flooding with actual rainfall impacts, Bandy says that the predictions “were pretty close.” Although Irene dropped about the same amount of rainfall as Hurricane Floyd in 1999, river flooding was not as significant because of low water levels prior to the storm.

Four days before landfall, researchers from the Coastal and Inland Flooding Observation and Warning project, or CI-FLOW, began running models, and making river-flooding and storm-surge inundation predictions for the area. The experimental system was developed after Hurricanes Dennis and Floyd to improve real-time water level predictions prior to and during tropical storm events.

The modelers and forecasters were pleased with the results from CI-FLOW. The model forecasted maximum water levels in the Tar-Pamlico and Neuse river basins, which came within 1 foot of the observed water levels in the selected test sites. The NWS forecasters had access to CI-FLOW to evaluate how well the system represented the interaction between storm-surge, sound and river water, and its impact on the coast.

Jack Thigpen, Sea Grant extension director, notes, “Although CI-FLOW is experimental and not a replacement for the standard forecasting models traditionally used by the forecasters, it adds another source of information to help the experienced forecaster make better predictions and reduce potential for loss of life and property damage.”

Coastal flooding due to storm surge in many areas was catastrophic and unanticipated by the public. The NWS forecast 18 hours prior to landfall was for extreme coastal flooding, meaning 8 feet or more of water above ground level, in parts of Carteret, Pamlico, Beaufort and Hyde counties. Other areas — including the entire barrier island chain north of Cape Lookout, and the Pamlico and Neuse river areas — were warned of high storm surge, with an expected 5 to 7 feet of flooding.

After the storm, measurements showed that about 4 to 6 feet of storm surge occurred above the ground level in areas of the Pamlico River. In the Neuse River, similar surge levels were measured, although some local areas had as much as 8 feet of water.

The forecast of coastal flooding due to storm surge was close to the observed levels but many residents were still unprepared.

NWS is improving forecasting, and striving to provide the public and emergency managers with better accuracy and longer lead time for emergency preparations. However, getting people to evacuate often is difficult. The experts focus on communicating danger with graphics, but even that information might not get people to leave.

“What we cannot convey with our warning maps is what it really means to stay behind,” Bandy notes. “It is not just still water. There are waves and it is extremely dangerous.”

WARNINGS IN 140 CHARACTERS

Many municipalities across the state are using Twitter, Facebook and other social media to expand their communications. Hurricane Irene was the first time several counties used these new communication tools for emergency management.

Donna Kain, faculty member in the technical and professional communications program at ECU, surveyed emergency managers about social media. She found that 55 percent are using social media and another 24 percent are likely to start using it in the near future.

“Social media has been adopted by larger county emergency management departments,” says Kain, who participated in a Sea Grant-funded study on risk perceptions and emergency communication effectiveness in coastal zones. “Most of the departments prepare the messages themselves, in addition to their other duties.”

Roberta Thuman, Town of Nags Head’s public information officer, spent Hurricane Irene in the emergency operation center listening in on calls from people who wanted to be rescued during the storm. This was the first emergency in which she was using Twitter to provide information to the public about the storm and the conditions in the area.

“I was the person sending out the tweets and I had to keep my emotions in check,” Thuman says. She started tweeting before the hurricane — and her Twitter followers grew exponentially during the storm. She was grateful that many of her posts were re-tweeted, especially ones that alerted people to rising waters and recommended staying inside.

In New Hanover County, emergency manager Warren Lee finds that social media is a good way to reach out to young people. The county uses Facebook, Twitter, Flickr and YouTube, in addition to traditional media such as newspapers or television.

“During Irene we had a 300 percent increase in Facebook followers with over 76,000 views and 204 tweets. In addition, we produced six YouTube videos showing the activities of the county’s Emergency Operations Center,” Lee says.

While social media is a way to reach people who do not rely on traditional media, adoption has been slow because many municipalities do not allow employees to access the sites on work computers. One of the lessons from Irene for emergency communicators has been that policies need to be developed about the use of social media, including how it will be staffed when a crisis occurs.

“The immediacy of Twitter and other social media is wonderful, but it is also a big challenge. You have to keep that in mind,” Thuman says.

HYPERLOCAL INFORMATION

Traditional news media, particularly television news, played an important role during Hurricane Irene. Local and national media turned to emergency managers and the NWS for information, but getting the local information people need often is challenging.

Irene showed emergency communicators the power of social media to share real-time and precise information. Social media plays an important role in filling the gaps for local information and offers an outlet for the news media to reach additional audiences.

Skip Waters, chief meteorologist at WCTI-TV, never had a desire to communicate via social media. With Hurricane Irene, he has seen its value. “The stuff that really resonates for people is the hyperlocal,” he says.

Hyperlocal is very specific in both location and time. It is the kind of information that Waters has from driving around his region, 19,000 miles each year — and the kind of knowledge that helps when using social media. There is value in “knowing every little landmark, every little store, every store that used to be there, every place that has a good cheeseburger,” he says.

During Irene, Travis Morton, the news station’s intern, adapted Waters’ on-air weather reports and descriptions to Facebook and Twitter to increase their communications reach. Tweeting or creating Facebook posts also can allow people to share what they are experiencing in their neighborhoods. For example, comments from viewers via social media provided verification of storm impacts, often in real time.

However, some of the biggest communications challenges occurred during the recovery, when many communities were without power for extended periods. Because of the hurricane, Waters says that the station evolved from just sharing information to understanding how people without power were getting much of their weather information through the station’s social media outlet via smart phones or other devices.

One viewer was thankful for the social media updates during the storm when she was without power for three hours. “Travis was my hero,” she told Waters.

VOLUNTEER WEATHER OBSERVING

Local information is sometimes difficult for the forecasters to obtain with limited numbers of weather stations around the state. That is where the Community Collaborative Rain, Hail and Snow Network, also known as CoCoRaHS, comes in. It is a volunteer weather-observing program that trains citizens to collect precipitation data and send it daily to the NWS.

“It is a good way for folks to get involved,” notes Brian Efland, coastal business specialist with Sea Grant, who is helping recruit volunteers. “Some counties in the region do not have any observers, so Sea Grant has funded 36 rain gauges for volunteers in rural locations along the coast.”

To be involved, participants must have a high-capacity, 4-inch diameter rain gauge and register with the CoCoRaHS website. Then each morning, the volunteer empties the rain gauge and records the amount of precipitation through the website.

During storms like Hurricane Irene, the CoCoRaHS volunteers provide detailed data that become part of tropical storm statements for NWS. Rainfall amounts also are incorporated into CI-FLOW and other models to help improve rainfall forecasting.

“One of the pluses is that the rain gauges do not rely on electricity, so they are great for storm totals and fill in the gaps between automated gauges. The CoCoRaHS network was also critical in ground truthing a new radar system put into place by the NWS just prior to Hurricane Irene,” says David Glenn, state coordinator for the project and NWS meteorologist.

NO ‘JUSTA’ STORM

Bill Read, recently retired director of the National Hurricane Center, spent his 35-year career studying hurricanes. One of his most recent efforts has been the Hurricane Forecast Improvement project, a 10-year program that began in 2009. While forecasts of the hurricane track have improved greatly, forecasts of intensity have not.

Irene was an example of how difficult it is to predict hurricane strength and speed. “A lesson learned from Irene is one I have seen in many storms. Even a good forecast has uncertainty. Getting locked into specific times and locations, especially before 48 hours, can cause misunderstanding,” Read says.

Hurricane Irene reminded meteorologists and emergency managers that there is no “justa” tropical storm or “justa” Category 1 hurricane. Each storm is different. In a severe thunderstorm, 60-mph winds may last seconds or minutes, but in a tropical storm the size of Irene, these winds can last hours.

“If I could rewrite history, I would not have any kind of scale,” Read remarks, referring to the categories used for hurricanes. “Mother Nature is a continuum.”

- Information on hurricane preparedness is available at: readync.org and www.ncdhhs.gov/hurricanes. Many county and town websites also have good resources.

- For research on weather preparedness see: www.ecu.edu/riskcomm.

- See a video describing the Coastal and Inland Flooding Observation and Warning Project at: https://ciflow.nssl.noaa.gov/.

- Find out if you are at risk for flooding at: www.ncfloodmaps.com.

- To volunteer to be a CoCoRaHS observer in North Carolina, contact David Glenn at: david.glenn@noaa.gov. In the coastal region, contact Brian Efland at: brian_efland@ncsu.edu. For more on CoCoRaHS, visit: www.cocorahs.org.

This article was published in the Autumn 2012 issue of Coastwatch.

For contact information and reprint requests, visit ncseagrant.ncsu.edu/coastwatch/contact/.