Plymouth Prepares for the Future: Flooding Threats in a Changing Climate

Plymouth Mayor Brian Roth has a big window in his office that overlooks the Roanoke River. The river has been the lifeblood of the historic town since its founding in 1787, when the rivers in North Carolina were the main transportation routes for the traditional agricultural and forestry products of the region. Boat traffic on the Roanoke is mostly recreational now, but the river and its resources still are a key amenity to the community.

The seat of Washington County, Plymouth is seven miles from the mouth of Albemarle Sound. “We are extremely fortunate,” Roth explains, “to be located geographically where we are. The Roanoke River is incredibly rich with biodiversity. The N.C. Wildlife Resources Commission biologists often refer to the lower Roanoke River as the crown jewel of North Carolina rivers. So from an ecological standpoint, you know, it’s just amazing what we have right here.”

But sometimes there is too much water. Like many of the other waterfront towns in the region, Plymouth has a flooding problem. Many of the residents say that it has gotten worse in recent decades.

Much of the sewer system for the town is almost 100 years old and is experiencing problems. Ken Creque, town manager, is often on the receiving end of the calls for help. “The big thing has been standing water. That’s the one thing that people call me up on the phone and complain about — the water, the water, the water. Why is water coming over my yard?” he says.

Although Plymouth has completed significant sewer improvement projects over the last decade, town leaders face new challenges likely due to changes in water levels. The threat of flooding from the river during storms — such as Hurricane Irene in 2011 — also has increased the urgency of the situation.

Jessica Whitehead, regional climate extension specialist with North and South Carolina Sea Grant programs, told city leaders, “Stormwater and wastewater flooding problems in this area are influenced by climate stressors such as rainfall variability, including how much rainfall are you getting at one time, and water-level rise. That could be water level from storm surge, or that could be the long-term sea level rise.”

Roth is on a mission to find solutions for Plymouth. “One of my major pushes that I implemented when I came in as mayor was to seek funding to significantly rehabilitate our sewer collection system,” he explains.

He uses a traveling slide show to demonstrate the problem. Roth has pictures of manholes gushing water into ditches. Slides depict the position of the sewage treatment plant, which is elevated out of the flood zone, but becomes an island during a flood. Other images illustrate the depth of water around the pumping stations during hurricanes, such as Isabel in 2003.

For the last few years, Roth has taken his slide show to government and private partners who could help the town overcome the flooding problem that has overtopped the riverside pumping stations, caused sewage spills and drained the coffers of Plymouth taxpayers.

FORTUITOUS MEETING

In February 2010, Roth attended the Southeast Adaptation Planning Workshop in Atlanta organized by Ken Mitchell, senior climate advisor for the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and a Plymouth native. The conference explored how federal agencies, states, local municipalities and private firms can work together to find solutions to municipal problems that will be made worse by future climate variability.

Gloria Putnam, North Carolina Sea Grant coastal resources and communities specialist, also was at the conference. She knew of an opportunity to help Plymouth seek strategies to fix their flooding problem. “Here we had a community that had an interest and had an issue. We had an elected official that was interested in our project and wanted to do something with us,” she recalls.

The project was part of the National Sea Grant Coastal Communities Climate Adaptation Initiative, a $1.2 million program launched in 2010 and spread over 200 communities across the coastal United States. North Carolina Sea Grant successfully obtained funding to work with Plymouth.

Later, the team also was able to take advantage of planning tools developed by the Social and Environmental Research Institute, or SERI; the Carolinas Integrated Sciences and Assessments Center at the University of South Carolina; and the South Carolina Sea Grant Consortium. The organizations received grant funding from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Sectoral Application Research Program, which supports research to help communities making climate-related decisions.

“Working to help coastal communities is a big part of our outreach program. However, this was really our first experience with this topic, so Plymouth and our other partners all learned about how to tackle these issues together,” says Jack Thigpen, Sea Grant extension director.

WE LOVE OUR RIVER

The first phase of the Plymouth project took place in late summer 2010. Staff from Sea Grant and East Carolina University interviewed 18 Plymouth civic leaders to understand their perspectives. Each leader shared observations, experiences and thoughts about local environmental change.

Most of the leaders had lived in the area for more than 40 years. Many held elected office or were on governing boards of civic, religious or not-for-profit organizations. They spoke about how the town had changed over time. Their comments were collected anonymously as part of the research project.

One long-time resident said, “I look at it [Plymouth] as a diamond in the rough. But in terms of environmentally, I would say [it is] improving. I’ve lived here long enough that I can remember the paper mill odor and you could see the fumes being emitted. In the springtime, the herring would run up the river and you could go out here with the drift net and catch herring, and part of that experience was smelling the paper mill, and they’ve cleaned all that up.”

The Roanoke River, nearby Albemarle Sound and three National Wildlife Refuges are vital to the life of the community. Plymouth hosts fishing tournaments and boat races that bring water-recreation lovers to the area.

Nature enthusiasts and bird watchers can find a wildlife trail along the river just to the east of downtown. Paddlers have access at Conaby Creek, located right in town, which connects to a system of camping platforms along the Roanoke River.

When one leader was asked about Plymouth’s assets, she said, “I think of the great natural resources that we have here — to the river, to the sound, to great hunting land, to wildlife refuges — from the recreational standpoint and from a conservation standpoint as well.”

But with the river comes the challenges of flooding, the major environmental issue mentioned during the interviews. Reasons for flooding in Plymouth include extensive areas of low-elevation land and previous roadpaving practices.

One leader said, “I know Plymouth is a pretty flat town. A problem for property owners is that there’s nowhere really for the water to go because everything is flat. Some of the older homes are actually built below the street level so that naturally leads to flooding problems.”

Flooding is caused by intense rainfall from severe storms and hurricanes, and rising river levels from storm surges and wind tides. During Hurricane Irene in 2011, Plymouth suffered flooding from storm surge and wind that brought down trees. Many of the civic leaders are concerned about how future water levels will impact the streets and yards already slow to drain.

“We are elevationally challenged to some degree and, long term, that will kick in,” said a Plymouth resident. “The biggest problem that Plymouth had was from the river when it flooded. And when the river’s up, we get flooding now.”

SMART MAPS

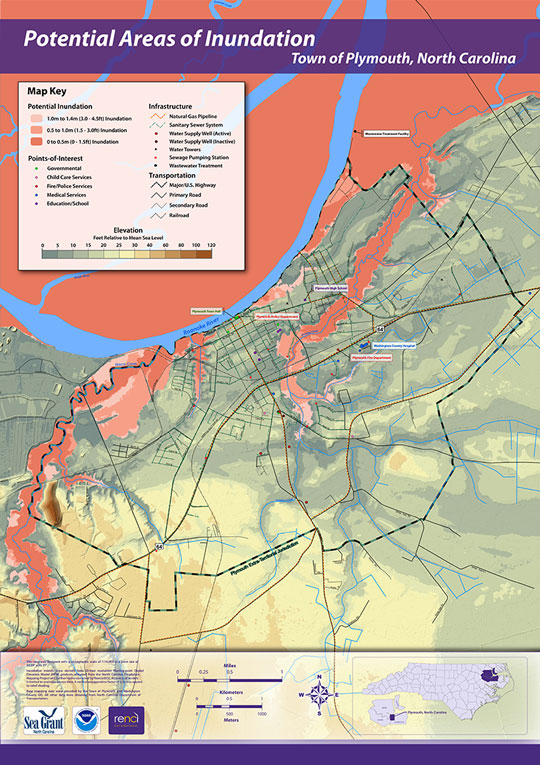

To examine the potential threat to Plymouth from future higher sea levels, the Renaissance Computing Institute East Carolina Regional Engagement Center, located at ECU, was asked to determine areas of the community most at risk of flooding. Tom Allen, geographer and center director, led a team to create maps of potential areas that would be inundated with 1.5 feet, 3 feet and 4.5 feet of additional water.

“Maps are smart. They can guide you away from hazards and toward sustainable development. They are key to adapting to climate change,” Allen notes.

The Plymouth maps highlight the land most vulnerable to flooding from the river. Overland flow of river water is possible if there is significant flooding upstream or wind-driven storm surge from the Albemarle Sound during a hurricane or severe storm.

The maps show large swamp areas to the north of Plymouth and land adjacent to creeks as the most vulnerable to inundation. These wetlands have been recognized by leaders to serve an important function in flood control and water quality. One said, “We’ve got, going north from here, four miles of swampland. That’s what swampland is for — to absorb flood. Then as the water flows out, it filters it out.”

The maps also demonstrate that key community infrastructure — such as roads, buildings and the wastewater treatment system — is vulnerable to inundation from a rise in river water level. When community leaders mapped areas that they knew flooded during storms, most of the commonly identified areas closely matched the most vulnerable areas on the map depicting potential future inundation due to sea level rise.

The map depicts a model used to calculate areas of Plymouth that could be inundated depending on changes in water level. Based on the elevation measurements from the N.C. Floodplain Mapping Project and the connectivity of an area to the river or tributary. This map assesses potential vulnerabilities and general risk awareness. It should not be used for site-level insurance or flood-risk analysis.

Tom Allen, director of the Renaissance Computing Institute East Carolina Regional Engagement Center at East Carolina University, and graduate student Robert Howard produced the map. “Maps are a key tool to show location and awareness of resources, potential conflicts and opportunities,” Allen says. He would like to see maps, visualizations and resources available to other communities and organizations planning for climate change.

Every leader interviewed for the project was aware of the flooding problem in Plymouth and thought it was very important to address the issue. Unfortunately, economic conditions and other obstacles have prevented action. One leader noted, “Well, we need to work on the flood problem…as money comes available.”

EXPLORING OPTIONS

To explore the flood mitigation options that Plymouth might have, Whitehead facilitated a workshop in October 2011 to help community leaders discuss their options. She introduced Vulnerability and Consequences Adaptation Planning Scenarios, known as VCAPS. Whitehead was on a team, along with researchers from SERI and the University of South Carolina, that developed VCAPS and had previously used it in two South Carolina communities. The planning tool allows leaders to build a diagram depicting the relationships between environmental stresses, such as increased water level, and management concerns, such as flooding.

As a result of increased water level from storms, Plymouth leaders discussed how the inflow and infiltration of rainwater into the sewer pipes resulted in consequences, such as sewer overflows at pumping stations and inundation of the sewer treatment plant. Both management and individual actions to respond to the consequences of increased water level were illustrated to help the group think about possible solutions.

The VCAPS process uses a structured discussion format, but does not dictate a specific outcome, so everyone was able to participate freely to find unique solutions for Plymouth.

“I think the VCAPS process was an opportunity for everybody to see the same information displayed at the same time and have an opportunity to synergize our knowledge base,” Roth says. “I think you did a very good job of bringing people from different specialties into the room but we all are stakeholders and we need to know what everybody else is thinking so it was an opportunity to get everybody together and get information out on the table in a format that was easily digestible.”

The opportunity to work through one issue at a time and brainstorm individual solutions benefited all the participants, Roth adds.

In addition to the management solutions, the workshop allowed civic leaders to learn from each other. Staff and consultants working for Plymouth had the opportunity to create a deeper understanding among the elected officials of the challenges they are facing in their efforts to minimize flooding. Elected officials were able to share their perspectives and concerns.

After dedicating five hours to a better understanding of how Plymouth might address their stormwater and wastewater concerns, leaders noted they had gained a more holistic perspective. “I think that it is easy to look at issues individually and address them. It is more difficult to look at them from a comprehensive point of view,” one explained. “I think this was a better way to look at it, versus breaking it down into little pieces and parts. I mean the model itself or the VCAPS diagram is obviously broken down into several parts, but it came back and tied stuff together.”

One elected official who participated in VCAPS said that the process was very beneficial to understanding the financial aspects of addressing the flooding problem. “This is real different. Truly, I think that your council, your leaders, whether it is council, commission, whoever, should be more involved and they might understand much better what you all have to go through to even get funds for us.”

When asked if the VCAPS process has helped Plymouth prepare for future water levels, one leader responded, “I think that you will see them take a more proactive approach. I think the county as a whole will be impacted by climate change. Now, I will say that I have seen some mitigation efforts that have taken place within the town’s jurisdiction.

“So I think that things will change for the better because they are taking more of a proactive approach versus reactive,” the leader concluded.

PREPARING FOR WATER RISE

Plymouth is looking to the future and preparing for the next time the town will need to deal with flooding. Anne Keyes, director of planning and safety for Washington County, notes, “We’ve identified hazards through our hazard mitigation plan, the hazards that we are most vulnerable to. We participate in our four-county region including Martin, Washington, Tyrrell and Hyde counties. We have decided that through the state’s pilot program that we would do a regional hazard mitigation plan to identify our hazards. Even though the three [other] counties are similar, we are also different, so we can pull from each other’s strengths and weakness to assist each other.”

What is the next step for Plymouth? Roth says, “We have owned up to the fact that we are vulnerable to water advance, so I think we are good there. So now, what has to happen is that we need to keep on the course that we are headed that will eventually lead to funding. We need enough funds to rectify the problems.”

CLIMATE RESOURCES FOR COMMUNITIES AND EDUCATORS

Check out the resources below to learn more about coastal flooding, climate change, sea level rise, and what that might mean for you and your coastal community. These links have information and tools to help with planning for climate change.

- North Carolina Sea Grant–Planning for Change: www.ncseagrant.org/s/climate

- N.C. Climate Change Initiative: www.climatechange.nc.gov

- State Climate Office of North Carolina: www.nc-climate.ncsu.edu

- Southeast Regional Climate Center: https://sercc.com/

- N.C. Division of Coastal Management Sea Level Rise Information Page: portal.ncdenr.org/web/cm/sea-level-rise

- N.C. Sea-Level Rise Risk Management Study: www.ncsealevelrise.com

- Carolinas Integrated Sciences and Assessments: www.cisa.sc.edu

- NOAA Coastal Services Center Digital Coast: www.csc.noaa.gov/digitalcoast and Sea Level Rise and Coastal Flooding Impact Viewer: https://coast.noaa.gov/digitalcoast/tools/slr.html

- NOAA Office of Ocean and Coastal Management Climate Change Planning Guide for State Coastal Managers: https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=1&ved=2ahUKEwjtvLTh29jlAhXKqlkKHTG-BMUQFjAAegQIBhAC&url=https%3A%2F%2Fcoast.noaa.gov%2Fdata%2Fczm%2Fmedia%2Fadaptationguide.pdf&usg=AOvVaw0r_kUJvUDzOoZUKlqfnXvk

- Georgetown Climate Adaptation Tool Kit: www.georgetownclimate.org/adaptation and search for the tool kit under Featured Documents

- National Ocean Service Coastal Climate Adaptation:

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Climate Change–Health and Environmental Effects in Coastal Zones: www2.epa.gov/cre/climate-change-coastal-communities

This article was published in the Spring 2012 issue of Coastwatch.

For contact information and reprint requests, visit ncseagrant.ncsu.edu/coastwatch/contact/.

- Categories: