Undersea Exploration: Charting New Pathways to the Abyss

Oceans run the planet. They provide our food, steer our weather, support our commerce and drive Earth’s water cycle. More than 70 percent of the world’s surface is covered in ocean waters — collectively the largest ecosystem on the planet.

Yet, we still have a lot to learn about what makes it tick, says Steve Ross, marine biologist at University of North Carolina Wilmington’s Center for Marine Science.

In fact, only a small percent of this vast frontier has been scientifically documented and described, adds Ross, who has been studying the Atlantic Ocean and Gulf of Mexico deep-sea environments for more than three decades.

This spring, Ross and colleagues embark on the final voyage of an ambitious four-year project designed to fill at least part of that knowledge void. The cruise is slated for May 2 to 27.

Ross, Sandra Brooke, a coral researcher from Florida State University, and Rod Mather, who teaches marine history and underwater archeology at the University of Rhode Island, are leading an effort to unlock the mysteries within and adjacent to the Mid-Atlantic Ocean’s Baltimore and Norfolk deepwater canyons off the coasts of Maryland and Virginia.

The expedition, called Deepwater Canyons: Pathways to the Abyss, sounds like a science fiction adventure tale. But, make no mistake. This is real science conducted in real time by a multidisciplinary, international team of researchers who are fueled by intellectual curiosity and determined to chart new pathways in ocean science.

Their objectives include locating cold seeps and other vulnerable habitats, describing the canyons, investigating the biology and ecology of different types of seafloor communities, and identifying archeological sites — including historic shipwrecks.

Results from documenting these unique habitats and their inhabitants could help guide future uses for and protection of these ocean resources, Ross says.

BUILDING ALLIANCES

The deepwater canyon exploration is funded by two organizations: the U.S. Department of Interior’s Bureau of Ocean Energy Management, also known as BOEM; and the National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration’s Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, or OER. NOAA ships provide platforms for operations at sea — the Nancy Foster for the 2011 and 2012 Pathways cruises, and the Ronald H. Brown for the upcoming 2013 journey.

In addition, the project is supported by contributions of both personnel and equipment from the U.S. Geological Survey, or USGS, and partners from multiple institutions and agencies in this country and from Europe. The expedition relies on the N.C. Museum of Natural Sciences and OER for their strong education and outreach component.

The coalition of talent and support for the project is not surprising to Susan White, executive director of North Carolina Sea Grant. There is no scarcity of scientific interest in exploring the vast wilderness of mountains, canyons, plateaus, marine organisms and abundant untapped resources that lie deep beneath the oceans, she notes.

However, shrinking funding sources for launching major enterprises requires building strong alliances among researchers and institutions that share similar interests, goals and objectives. Beyond the financial imperative for funding ocean exploration, White thinks such multidisciplinary, intrauniversity/intra-agency alliances make good science sense.

“It’s an approach that provides a cross-pollination of ideas. The skills and knowledge of each researcher and institution complement the other. No one can do it all, and it’s exciting to see how partnerships can leverage resources to get the work done,” she says.

White should know. At Sea Grant, she heads an organization that spans research topics, universities and agencies, and that is recognized for bringing stakeholders together.

BUILDING MOMENTUM

With two cruises completed, Ross, Brooke and Mather describe preliminary results so far as “very productive.”

The first phase of the project began in 2011 with an expedition to map the seafloor of the targeted research areas. Using multi-beam sonar technology, they navigated across shipwreck sites to pinpoint positions of the known sunken vessels. They also trained the beams on the geographic features of the Baltimore and Norfolk canyons, which Ross describes as “extremely rugged and as awesome as the well-known Grand Canyon.”

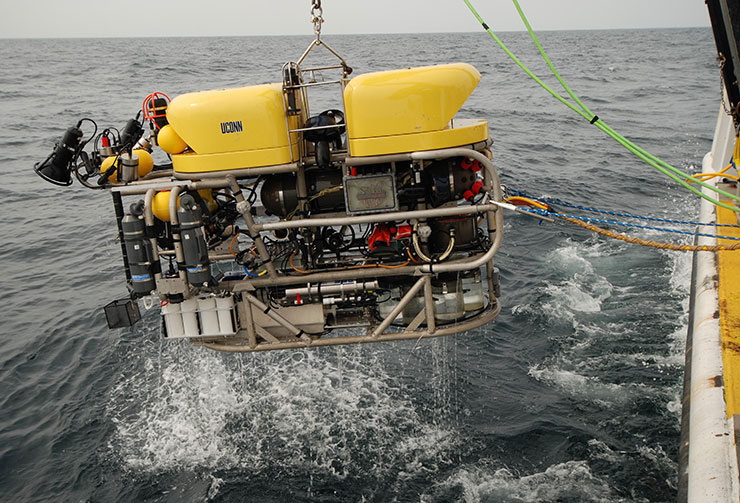

The 2012 Pathways to the Abyss cruise, Aug. 15 to Sept. 30, sought to groundtruth the multi-beam maps using the “eyes” of Kraken II, a Remotely Operated Vehicle, or ROV, owned by the University of Connecticut. In addition to collecting biological samples, the ROV relayed hundreds of still and video images topside to an excited audience of waiting researchers throughout the cruise.

Findings from the 2012 cruise include the “rediscovery” of a methane cold seep first encountered 30 years ago; the first documentation of the presence of Lophelia pertusa, a deepwater coral, in Baltimore and Norfolk canyons; the discovery of several new animal range extensions, including a species of seep mussel; evidence of ancient riverbeds; and the documentation of World War I-era German warships sunk during General Billy Mitchell’s demonstration of air power.

Each deep ocean mission is carefully orchestrated to maximize the use of skills, technologies and precious time at sea. Teams match the specific scientific objective of each cruise leg, the researchers say.

The 2012 cruise was divided into three legs. Ross and Brooke led Legs I and II — Aug. 15 to Sept. 14 — concentrating on natural ecosystems and habitats within and around the canyons. Mather coordinated Leg III, that ran from Sept. 15 to 30, focusing on continental shelf geology and archeology, and historical shipwrecks and their biological communities.

To maximize ship time, the researchers conduct round-the-clock operations. In daylight, the ROV is deployed to survey and record habitat, sunken vessel sites, biological communities and canyon or seafloor characteristics.

Night crews launch scientific equipment to take core samples from the seafloor and from incremental heights of canyon walls. Crews use small trawls to collect fauna and sediments. Water samples from various depths also are collected during night shifts.

“We also maximize our sampling efforts,” Brooke points out. “For example, one sample of bubblegum coral could be snipped into a dozen slices for different analyses — reproductive, genetic, isotopic, paleo and so forth.”

The plethora of samples from the 2012 cruise — from fish to sediment cores, water and corals — are being analyzed in laboratories of participating Pathways researchers across the country, from North Carolina and Oregon to Rhode Island, Connecticut, Florida and Louisiana, as well as in Ireland and the Netherlands.

MAKING DISCOVERIES

Ross and Brooke agree that it’s hard to stay professionally detached when you are part of a research team documenting “firsts,” such as sighting Lophelia pertusa in the Baltimore and Norfolk canyons.

The deepwater coral is well documented in the Gulf of Mexico, and in waters off the Southeastern U.S. and the New England coast, thanks to previous NOAA-BOEMUSGS-funded projects. But, there had been no observations of this coral in Mid-Atlantic waters.

“The discovery filled a gap in our knowledge of the distribution of this important coral species,” says Brooke, who has studied reproduction in deepwater corals for more than a decade.

The Mid-Atlantic Lophelia pertusa have distinct characteristics in location and shape, she adds. They tend to be spherical and compact, and are found on the underside of overhangs or other areas that are protected from strong currents and sediment accumulation. Studies are underway to determine if they share the same DNA as their New England and Southern lookalikes.

During the 2013 cruise, Brooke will look for additional Lophelia pertusa and try to understand the stepping-stone effect of coral reproduction — how far larvae can travel within a three-week window of viability.

The Pathways researchers also were excited to “rediscover” the Baltimore Canyon methane cold seep that was first identified more than three decades ago by Barbara Hecker, then a lead scientist for a NOAA-funded Baltimore Canyon exploration.

“She was using a towed camera to survey the seafloor,” Brooke says.

When Hecker processed the film later, she spotted images of mussel beds, which are indicative of a methane cold seep. Methane seeps, host to a unique biological community, are a possible indication of the presence of valuable hydrocarbons.

Hecker was using very old technology that produced unreliable sea coordinate readings, so her 1980s description gave Ross and Brooke only a “sort of” location.

“Going by Hecker’s more reliable depth sensor records, we had a starting point for navigating the ROV dives over transects around the approximate coordinates and known depths. When we began to see patches of white bacteria and telltale mussels, we knew we were on to something,” Ross recalls.

The researchers will redirect ROV dives to the seep this spring to further map the site and document its unique animal communities. They also will search for other seep sites. Meanwhile studies are under way to pinpoint the species of sample mussels and various aspects of their biology.

REDISCOVERING HISTORY

From an archeological perspective, exploring the Mid-Atlantic deepwater canyons provides a view of both ancient and modern times, according to Rhode Island’s Mather. “It’s a previously unstudied archeological area and the Pathways project is providing baseline information of what is there,” Mather points out.

“Some 10,000 to 15,000 years ago, what is now a submerged continental shelf was dry land. Exploration tells the story of the intersection of land and water in the past. It’s a big contextual piece of history,” he says.

Mather and his team are searching for remnants and clues of human habitation sites. So far, they have identified landscape features from that prehistoric era — ancient river beds, river rock and high ground where populations likely would have settled. But no artifacts have been spotted on ROV video footage. To be sure, the search will continue this spring.

What have been identified, though, are eight shipwrecks from the so-called Billy Mitchell Fleet, including the battleship Ostfriesland and the cruiser Frankfurt.

At the end of World War I, a dozen or so German ships and submarines were relocated to U.S. waters.

Mitchell, armed with Martin BM2 biplanes, “attacked” and sunk the ships to demonstrate air power over what then was considered the most powerful of war machines. His success helped launch today’s U.S. Air Force. Mitchell also has a North Carolina connection — the airport on Hatteras Island bears his name.

“What is evident at all wreck sites is the real damage from heavy fishing gear and nets,” Mather reports.

The shipwrecks are being assessed for the possibility of their being listed on the National Register of Historic Places, a designation that would help protect an important chapter in nautical and aviation history.

The sunken vessels also are being evaluated for their importance as “artificial habitat” for a variety of fishes and invertebrates — not surprising considering the documentation of an aggregation of spawning catsharks at one of the wreck sites.

Mather says Jason II, a powerful ROV from Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute, will be available for the spring cruise on the Ronald Brown. “It will provide a higher level of documentation at the important archeological target sites,” he says.

He also is looking forward to reconnecting with Pathways’ education and outreach component that brings the ocean to the world at large through the Internet.

“We live in an age of communication — and science cannot exist in a vacuum. Education and outreach captures the public’s attention. An informed public can ultimately inform public policy,” Mather says.

LOGGING ON

For her part, Liz Baird, director of education for the N.C. Museum of Natural Sciences, is ready to cast off and log on for the 2013 Pathways cruise.

Baird has been an integral member of UNCW-led ocean exploration team since the 2001 Islands in the Stream exploration of Southeastern and Gulf of Mexico waters. Baird helped the public learn more about undersea research and exploration through Internet and email exchanges.

“We called it ‘near real time’ in those days,” Baird recalls. “Before Internet’s instant communication capacity, we relied on a satellite passing over three minutes each day to relay responses or receive queries in what was then state-of-the-art ‘interactive’ education and outreach.”

Now, communication between ship and shore is instantaneous and around the clock. “We can post researchers’ daily blogs, tons of pictures and unlimited information, and respond to queries immediately. And, we Skyped three times during the 2012 mission,” she says.

When she’s not busy communicating sea science, Baird assumes duties as part of the on-board research activity.

“It’s challenging to learn to pace yourself. A 12-hour shift is only theoretical and usually runs till the work is done,” she quips.

On past cruises, Baird had the opportunity to dive in Sea Link, a four-man submersible vehicle operated by Harbor Branch Oceanographic Institute at Florida Atlantic University. “It was a huge privilege to be able to explore and explain places that you can’t see anywhere else on earth. It definitely inspires a sense of wonder,” Baird says.

She recalls a submersible dive that involved the excitement of her first sighting and capture of a lionfish off the coast of North Carolina. On another dive, she saw and captured an odd fish that turned out to be another tropical species that had not been previously documented that far north.

In 2011, financial pressures forced Harbor Branch to “mothball” its two submersibles after selling R/V Seward Johnson, the institute’s ship specifically outfitted to deploy submersibles.

Alvin, the Navy-owned submersible at Woods Hole remains the only manned vehicle for specialized deep-sea research on the East Coast.

With the loss of submersibles from the ocean research “tool box,” ROVs are surrogate underwater hands and eyes, but lack the 360-degree visibility of a submersible.

Baird’s sense of wonder — and desire to share it with the land-locked world — doesn’t end when the research ship docks. Rather, she fills museum exhibits with images and information from the deep in hopes of bringing her experiences to museumgoers and visitors to the museum’s website as well.

She also heads the North Carolina Sea Grant Advisory Board and has been an active partner with Sea Grant marine education.

The public wants to understand their natural world, she explains. The museum is a platform for unbiased, research-based answers and a forum for public discussion. And, not just for scientists to talk with other scientists, but a place to convey knowledge about the world.

Baird looks forward to the spring research cruise and the “chance to work and learn alongside amazing folks and to share their discoveries with the world through education and outreach.”

To learn more about the people and mission of the Mid-Atlantic Deepwater Canyon: Pathways to the Abyss project, visit deepwatercanyons.wordpress.com. For details about NOAA-funded ocean exploration projects, go to oceanexplorer.noaa.gov.

This article was published in the Spring 2013 issue of Coastwatch.

- Categories: