CLIMATE CHANGE COMMUNICATION CHALLENGES: Including Kids in Solutions

• Kathryn Stevenson is a faculty member in parks, recreation and tourism management at North Carolina State University. She focuses on environmental and climate literacy, having worked as a marine-science educator in California, and as a high-school biology teacher. Her doctorate in fisheries, wildlife and conservation biology from NC State included a North Carolina Sea Grant-funded statewide survey on environmental literacy among the state’s middle-school students.

• Danielle Lawson is a doctoral student whose Sea Grant-funded research focuses on climate literacy. She has previous experience as an informal educator. As an AmeriCorps volunteer, Lawson worked with middle-school minority students enrolled in MarineQuest camps at the University of North Carolina Wilmington.

Kids think differently than adults. New parents may notice their child delights in the seemingly mundane, squealing in unbridled joy at bouncing a ball down a set of stairs. Teenagers may be keenly aware of how their parents disparately value keeping a tidy room or making curfew. Teachers, students and parents may have varying perceptions of homework’s importance.

Our research out of North Carolina State University suggests that we may be able to use these differences to build a brighter future. Since 2010, North Carolina Sea Grant has funded three projects to investigate the potential for younger generations to be part of a solution to influence acceptance of — and action on — climate change.

SHAPING PERCEPTIONS

Climate scientists agree: Climate change is happening, humans are responsible and the potential impacts will be widespread. In the Southeast, sea-level rise, extreme heat events and decreased water availability pose threats to our communities, economies and ecosystems, according to the third National Climate Assessment.

Though the science is clear, public opinion regarding climate change remains divided. Sometimes attributed to a lack of scientific knowledge, this gap actually appears to widen with increasing science literacy, according to the research. Data may be shaped to support a person’s perception of climate change, but it’s not why they have their opinions. Cultural worldviews and political beliefs seem to drive climate change concern more than scientific understanding.

How do these powerful worldviews and beliefs form? Our upbringing and life experiences shape the framework we use to understand and interpret the world around us. Adolescence represents the formative window during which we establish our cultural and political beliefs. During this time, kids might base their opinions on an issue less on what they inherently believe and more on what they learn.

As part of our first Sea Grant-funded study, we surveyed around 400 middle-school students in coastal North Carolina to examine this idea of how learning may influence their views on climate change. We found that as student knowledge increased, the gap in opinions about climate change associated with personal beliefs disappeared instead of widened as it does with adults. Kids with more knowledge were more likely to respond that climate change is happening and human-caused.

“This study demonstrates why I like this line of research,” says Nils Peterson, the study’s co-author. “Working with kids represents an opportunity to make a lasting difference.”

IN THE CLASSROOM

If kids rely less on their personal beliefs than adults do when forming opinions about climate change, learning more about the science could make a real difference in driving their concern and behavior.

Project WILD, an environmental education program, fosters behaviors that respect wildlife and natural resources by developing students’ environmental literacy. In a second Sea Grant-funded project, new members added to the research team — climatologists from the State Climate Office, N.C. Wildlife Resources Commission biologists and Project WILD educators — helped create a Project WILD unit for middle-school students on how climate change affects wildlife in the state.

We then conducted professional development workshops for middle-school science teachers statewide to introduce the new curriculum. Participating teachers agreed to deliver the lessons and survey their students. Surveys measured not only how much students understood of climate change, but also their feelings about the topic and motivation to take action.

“I believe climate education is crucial to all individuals that call planet Earth home,” notes April Cheuvront, an eighth-grade science teacher at Avery County Middle School in the mountains and a workshop participant. “Therefore, it needs to be integrated into the curriculum for all ages of students.”

Students exposed to the new curriculum did show gains in climate-change knowledge. That new understanding seemed to increase two things: their concern for climate change and also, their hope.

“I found the lessons extremely beneficial for students to see how climate change affects North Carolina species. Too often, students believe that climate change is just a ‘polar bear/penguin’ issue. However, these lessons stress that many organisms will face consequences of climate change. The lessons also show how students, as individuals, can make a difference,” Cheuvront explains.

This hopefulness is important because greater concern and hope seem to drive action. After the lessons, students reported they were more likely to conserve energy or choose to bike or walk instead of riding in a car. In short, the curriculum worked.

OUTSIDE INFLUENCES

But, as any parent with school-age kids knows, knowledge is not the only influence on students. Teachers can profoundly impact their students’ learning.

Recent research published in Science shows that science teachers remain divided on climate change like the general public, with their personal beliefs influencing how they present climate change in the classroom. This raises questions about whether teachers pass on this difference in opinion to their students.

So far, our data show that students whose teachers thought climate change is happening were more likely to agree. However, teachers’ beliefs in the causes of climate change had no relationship with the kids’ thoughts. If teachers think climate change is happening, their students are likely to determine it is caused by human actions rather than occurring naturally, regardless of their teacher’s views.

“If you just teach kids the science, they get it,” says Amy Bradshaw, an NC State zoology undergraduate who co-authored a manuscript associated with this study.

And you don’t have to be a teacher to get kids learning and thinking about climate change. Just talking with kids seems to help, even if you don’t know all the answers.

Our research also looked at how kids’ own perceptions, the perceived views among their friends and family, and frequency of discussing climate change related to their concern about the issue.

Personal perceptions most closely predict climate change concern, according to our data. If they think climate change is happening and human-caused, kids are more likely to show concern. As shown by our earlier work, these personal perceptions of climate change can be bolstered through education.

The second most important factor related to climate change concern was how often the students talk about the topic with their friends and family. Interestingly, the actual views of their discussion partner did not matter — just having the conversations was important. Even among those who didn’t think their friends and family believed in human-caused climate change, talking more about the issue helped build students’ concern.

Kids’ perceptions about their friends’ and families’ acceptance of climate change also matters somewhat. Personal perceptions were most important, but knowing friends and family believe in human-caused climate change made kids more concerned.

“You don’t have to be a scientist to talk to kids about climate change,” Peterson explains. “Adults should share what they know, listen to any concerns, and talk about what actions can be taken to be part of the solution.”

THE HERE AND NOW

Parents certainly have influence over their children, but children also influence their parents. Advertising companies have known this for years. They market foods, amusement parks and clothing to children, even though parents actually make the purchases.

Research also shows that kids can influence their parents’ behaviors like recycling and leading more active, healthful lifestyles. The same principle may apply to climate change.

Our latest Sea Grant-funded study looks to evaluate how students may transfer climate knowledge and concern to their parents. We held additional professional development workshops in summer 2016 to train teachers in using our Project WILD curriculum. The research team also is working with local partner organizations to organize service-learning projects for students.

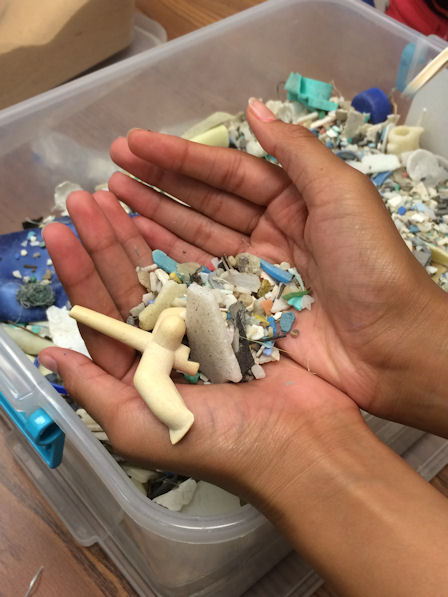

During the school year, students are conducting fieldwork, such as monitoring sea turtles or restoring wetland habitat, as a way to learn more about the effects of climate change and ways to contribute to solutions. Students will blog about their experiences in the field at go.ncsu.edu/wwcc.

“This project allows students to work with scientists, and become scientists themselves,” says Amy Lawson an eighth-grade science teacher in Pender County, and co-author Danielle Lawson’s sister-in-law. “My students will get hands-on experience with how wildlife and climate are impacted by nature and the actions of humans, as well as have the opportunity to build relationships within local and statewide community members.”

These experiences will help students think about climate change in a local context and understand how to make a difference. Teachers also will encourage students to talk about the issue with their parents. We researchers will conduct surveys throughout the program to evaluate its effectiveness.

“Experiences such as these allow my students in the small town of Burgaw to truly feel as if their voices matter,” Lawson affirms.

Climate change represents a big problem with big challenges. But there remains much hope in our children — and in our future.

PUBLISHED PAPERS

The North Carolina Sea Grant-funded research on climate change and middle-school children has yielded multiple peer-reviewed publications, including:

- “How climate change beliefs among U.S. teachers do and do not translate to students,” PLOS ONE, Sept. 7, 2016.

- “Are we working to save the species our children want to protect? Evaluating species attribute preferences among children,” Oryx, May 4, 2016.

- “The influence of personal beliefs, friends, and family in building climate change concern among adolescents,” Environmental Education Research, April 29, 2016.

- “Motivating action through fostering climate change hope and concern and avoiding despair among adolescents,” Sustainability, Dec. 23, 2015.

- “Overcoming skepticism with education: The interacting impacts of climate literacy on perceived risk of climate change among adolescents,” Climatic Change, Aug. 11, 2014.

Kathryn Stevenson lists additional papers at kathrynstevenson.wordpress.ncsu.edu under Research. Select News and Updates to read media coverage, including from NPR and the Washington Post.

This letter was published in the Holiday 2016 issue of Coastwatch.

For contact information and reprint requests, visit ncseagrant.ncsu.edu/coastwatch/contact/.

- Categories: