EDUCATION TO ACTION

This year, the dog days of summer seemed to drag on forever. The intense heat was no mirage: we sweated out the state’s second-hottest summer on record, with unusually warm temperatures continuing into October.

But according to the National Climate Assessment, future summers could melt this one right off the charts.

What will the North Carolina coast feel — and look — like in fifteen years? Thirty years? A hundred years? As surely as the sand on our beaches shifts over time, so too will our communities, economies and environment. With change inevitable, North Carolina Sea Grant is working with communities to make plans and choices that will sustain our coastal and ocean resources.

Like climate change, many of the natural-resource management problems we face in North Carolina are complex, requiring not only sound research and policy but also community support. “Our mission is to help improve management decisions — and we can’t do that without the public understanding the issues,” explains Susan White, Sea Grant executive director.

“By actively working with communities, we can help them better understand the science underpinning policies,” White adds. “We also can better understand their needs and help them engage with the data-gathering process. Public education provides an avenue to change both policy and the personal ways we interact with our environment.”

This emphasis on environmental literacy is not confined to North Carolina. The key to changing behavior, according to Louisa Koch, director of education for the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, is education. “We work to understand Earth’s systems so we can support better management of the planet to protect lives and property. Our information has little value if people don’t use it to make better decisions.”

From “pre-K to gray,” Sea Grant strives to bring science where it can make a difference. “Sea Grant has very important resources for helping people solve real-world problems,” Koch notes.

TEACH THE TEACHER

A common adage says: If you give someone a fish, they eat for a day; teach them to fish and they eat for a lifetime.

Teach them how to instruct others to fish — and you enable the world to eat.

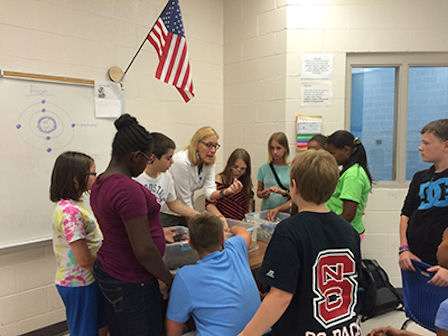

Sea Grant teaches educators how to share science with their students. “I work with teachers and nonformal educators to make sure they feel comfortable teaching their students about the ocean and our coast,” explains Terri Kirby Hathaway, marine education specialist for North Carolina Sea Grant.

Hathaway shares ways to help students understand how activities inland affect the coast and vice versa. She also ties these concepts to many parts of the K-12 curriculum. “If I can get teachers to use the ocean and estuaries to teach all their subjects, that’s really going to make a difference,” Hathaway concludes.

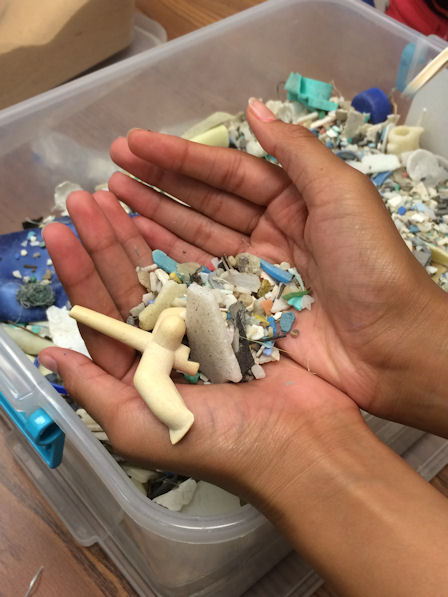

Another hallmark of many Sea Grant programs is place-based education, or connecting student learning to the local community, often through hands-on activities. Learning in this way has a longer-lasting impact according to Liz Baird, chief of school and lifelong education for the North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences.

“The best learning opportunities engage people’s minds in terms of learning knowledge, their hearts in terms of creating passion, and their hands in terms of giving them the skills and abilities to do things. Place-based and hands-on learning ties those three things together almost seamlessly,” explains Baird, who also is a past chair of Sea Grant’s advisory board.

Feeling the pressure to meet state standards, teachers may not pursue these types of learning, or even environmental literacy more generally. “Teachers report having very little time to do additional activities outside the classroom or the standard curriculum,” reports Lisa Tolley of the N.C. Department of Environmental Quality’s Office of Environmental Education and Public Affairs.

“Sea Grant helps teachers integrate environmental concepts in their classrooms by providing resources critical for increasing environmental awareness of coastal ecosystems and issues through its research, outreach and education.”

ASKING QUESTIONS, FINDING ANSWERS

Climate literacy represents a new area where Sea Grant may be well positioned to deliver those resources, starting with basic research into the what — and who — of effective communication.

Rather than focusing on how communities can become more resilient as the climate changes, arguments over the terminology and science can cloud perceptions. Nils Peterson and Kathryn Stevenson of NC State University, along with an interdisciplinary team of fellow researchers, educators and partners, have found reason to hope amid the climate change challenges: middle-school students.

“Middle school seems to be the sweet spot,” explains Stevenson, a former educator. “These students combine the wonder and excitement of younger kids with the cognitive ability of older students — without being jaded.”

White adds that, “middle school is a key period of science learning — not just from a curriculum standpoint but also from a sociological perspective.” They may not be old enough to vote, or even drive, but these early adolescents listen, learn and decide for themselves how to view the world.

A Sea-Grant funded survey of environmental literacy in middle-school students initially launched Stevenson’s interest and career in this research. She has since worked on two other Sea Grant-funded projects, while also transitioning from doctoral student to post-doctoral researcher to faculty member — all at NC State.

Those projects resulted in multiple surveys, new lessons for bringing climate into the classroom and now, an effort to engage students in service-learning as a way to literally bring the message home to the students — and their families. Read more about this research on page 9.

“Not only has this sequence of research built and enhanced strong partnerships within North Carolina, it also has generated results that stand the test of peer-reviewed publications. Requests for training and presentations are coming in from educators’ organizations, such as the Environmental Educators of North Carolina and the Southeastern Environmental Education Alliance,” adds John Fear, deputy director for Sea Grant.

“Ultimately, we want our work to make a difference on the ground,” Stevenson says. “We’re seeking to develop best practices for teaching climate change by understanding what teachers need and what is practically going to work to create change in communities.”

EDUCATION TO ACTION

Creating change in the classroom — and in a community — all comes down to understanding people’s interests. “People want to partner with organizations to find solutions to whatever challenges they face,” White says. “If you can see it in your backyard, you feel compelled to do something about it.”

This cooperative approach relates to the larger philosophy behind environmental education, Tolley explains. “It’s about providing people with the knowledge and skills to look at issues from all viewpoints and come to their own conclusions. It starts with building awareness, followed by knowledge, attitudes, skills and eventually participation.”

White sees education as a critical piece of the Sea Grant portfolio. “We need to educate students of all ages so that they not only find successful careers but also so they can work together to sustain our state’s future. Our program has had great success. We look to build on that success through new, and strengthened, partnerships.”

Several stories contained within this issue of Coastwatch illustrate this expansion. From grants that require community collaboration to joint fellowships with partner organizations and the rise of a network known as SciREN, Sea Grant works to frame the science so it brings people together and empowers them with information and tools they need to address real issues.

Some issues, like climate change, reach beyond our state’s borders. “What we choose to do with our environment in North Carolina can influence not only our neighboring states and the entire country, but also the rest of the world,” Baird surmises.

Tolley confirms that others are taking notice. “We really do hear from a lot of states that say: Wow, you guys have so much going on in North Carolina,” she recounts. “When you look around, we do have a lot of opportunities that are not found in other places.”

Opportunities for all ages to learn, teach and work together are valued and abundant in our state, White notes.

“How we work to sustain our coast with those resources will be the next big push,” she gathers.

This article was published in the Holiday 2016 issue of Coastwatch.

For contact information and reprint requests, visit ncseagrant.ncsu.edu/coastwatch/contact/.

- Categories: