FOCUS ON THE FLOW: WATERSHED RESEARCH BEGINS AT TRIBUTARIES

On the Cox Family Farm in Ramseur, N.C., two small tributaries drain runoff from approximately 40 acres of cattle pastures into Millstone Creek.

That creek flows to Deep River, one of the two headwaters of the Cape Fear River Basin.

About 130 miles from the farm, near Bald Head Island, the Cape Fear meets the Atlantic Ocean. The only major river in the state to flow directly into the Atlantic, the Cape Fear is known as an angler’s haven for bass, shad, sunfish and large catfish along with its commercial fishing industry near the coast.

The flow of that runoff — potentially from the Ramseur farm to the ocean — has the interest of Barbara Doll, water protection and restoration specialist with North Carolina Sea Grant.

“Right now, there’s sediment coming from stream bank erosion, and lots of nutrients coming from swine and cattle waste,” notes Doll, who also is on faculty in the Biological and Agricultural Engineering Department at NC State University.

With NC State colleagues, she is pioneering an urban stream restoration process on the inland farm, at the suggestion of state officials. “We hope to be able to remove some of the sediment and nutrients before they go into the main stream,” Doll adds.

Melonie Allen, wetland and modeling specialist for the N.C. Department of Environmental Quality’s Division of Mitigation Services, or DMS, explains that the site shows conditions common in the piedmont region of the state: streams affected by previous land-use practices, resulting in incised channels and eroding banks. Thus what’s learned at the Ramseur farm — and its implications for the larger watershed — can be applied in other locations.

“While the treatment area may seem relatively limited and removed from coastal waters,” Allen explains, “these site-scale opportunities to address water-quality concerns close to the source represent environmentally and economically sustainable measures that have the potential to expand their effect when applied throughout the watershed.”

• FROM LAND TO SEA

The Cape Fear River Basin contains 26 counties, with the Triad, Durham, Chapel Hill, Fayetteville and Wilmington being its most populated regions.

The watershed supports a bounty of commercial and recreational fish species, as well as some of the state’s largest industries, including a significantly concentrated cattle and swine region.

Runoff carrying fertilizers and animal waste washes into the basin’s streams and rivers from lawns, developed areas, farm fields and livestock operations. The runoff increases the flow of nutrients, such as nitrogen and phosphorous, into nearby waters, stressing the aquatic system, Doll explains.

These nutrients can stimulate the growth of algal blooms, causing eutrophication, or depleted oxygen levels that affect fish populations, she adds.

The NC State team is designing an innovative stream restoration technique — called regenerative stormwater conveyance, or RSC — on the Randolph County farm to determine if this method is effective at treating runoff from agricultural land.

“I’ve been interested in this type of approach,” Doll says. As a founding member and current co-chair of NC State’s Stream Restoration Program, she adds that implementing this technique on an agricultural site, rather than an urban stream, was “a good fit” for her research focus.

After the RSC design has been implemented, the researchers plan to monitor the site to determine if RSC is effective in a setting common to pastures in the southeastern United States.

• HOW RSC WORKS

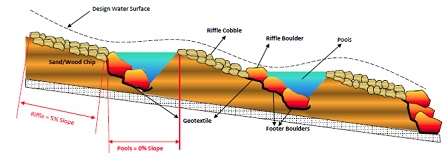

Originally developed for treating urban stormwater runoff, RSC typically involves filling an eroded channel with sand and mulch, and then constructing a water conveyance channel atop this layer to transport water during large storms.

The water conveyance channel consists of a series of shallow pools, riffles and native vegetation designed to filter out sediment and pollutants as the surface water flows through. In addition, as groundwater seeps through the media, it can infiltrate through the surrounding soil, helping to recharge the groundwater.

The subsurface flow, or flow through the sand and mulch layer instead of at the surface level, is what Doll notes is the most innovative part of the design.

“With some stream restoration projects, if the stream is reconfigured, it might be stable — the water would flow over the rocks and not cause erosion anymore. But it’s the subsurface flow of water through the sand and mulch that’s hopefully going to provide the most water-quality treatment,” she says.

The RSC design not only will stop bank erosion, but researchers are hoping it also will remove pollutants from the runoff water, Doll adds.

• AN AGRICULTURAL APPLICATION

The RSC design is being implemented in a pair of tributaries in the pasture in Ramseur, located 11 miles east of Asheboro.

The project grew out of interest by DMS, who is funding the construction. As RSC has gained popularity among researchers in the state, DMS identified the farm as a potential site to implement and study an RSC approach. The site already had been selected by DMS as a mitigation site, or site to alleviate the effects of other impacted streams within the water basin.

Other NC State colleagues, including Dan Line and Karen Hall, both extension faculty members in biological and agricultural engineering, are involved in the monitoring, survey and assessment components.

Jonathan Page, who focuses on stormwater-control measures at NC State, works with Doll as her design engineer. He explains that the team will ensure monitoring goals will be met by incorporating the necessary components.

“Some designs aren’t necessarily good candidates to be monitored and studied,” he notes, “so with us putting the design and plan sheets together, we know we’re going to get a system that can be studied and that we can learn from.”

In addition to the cattle pasture, the farm has hog houses and a lagoon. Animal waste stored in the lagoon is regularly sprayed on the pasture used for grazing cattle.

Many cow pastures across the Southeast use animal waste from farm lagoons or municipal wastewater treatment plants to supply the nitrogen requirements of the pasture. However, this often results in an excess of phosphorous in the soil, which can potentially wash into nearby watersheds and spur algal growth, Doll explains.

Often, methods to reduce the movement of pollutants and sediment require a relatively wide buffer, which can remove valuable farmland. Because of RSC’s capability of functioning without changing the existing stream corridor, the design may be ideally suited for use in the many eroded channels found in pastures across the Southeast and other regions of the United States.

“With typical stream restoration, often there’s a lot of grading to the existing stream corridor in order to change the pattern of the creek,” Doll notes. She adds that grading and moving dirt is costly, and can affect surrounding trees.

RSC is designed to have minimal impact. “You take the eroded gully and fill it up with media and build a structure, which is meant to be less disturbing to the environment,” Doll explains.

Page notes that the configuration of the two tributaries on the farm is ideal for a paired watershed approach — considered the best method of documenting effectiveness using water-quality monitoring data.

“The site has two adjacent highly incised, high-gradient channels that are good candidates for RSCs, and it’s also set up uniquely because the two tributaries come together at a confluence,” he notes.

One of the tributaries will be restored using an RSC design, and the other will remain unchanged. The researchers will monitor the stability, water quality and habitat of both channels before and after construction, enabling them to compare the streams and determine the effectiveness of RSC. In addition, the site may provide an excellent demonstration opportunity of the effectiveness of an RSC design.

“RSC functions differently based on the particular site,” Page notes. “We’re trying to get a grasp on the important functions to be able to implement those in other areas, and to get a reasonable understanding of the expected water quality and hydrologic function that might be gained.”

• AWARDS & ADDITIONAL RESEARCH

The field site and demonstration of the RSC design can be seen in a video, Water for a Growing World, produced by Doll, available at go.ncsu.edu/nzpq7w.

The video helped her earn an Outstanding Faculty Research Award from NC State’s College of Agriculture and Life Sciences, presented during the Stewards of the Future conference in November 2015. The award recognizes one faculty member’s pursuit of novel research in agriculture and life sciences. Doll is using the $5,000 award to continue monitoring efforts at the field site after construction.

The video is a play on typical Charlie Chaplin productions. The silent film stars Kevin Koryto, a master’s candidate in biological and agricultural engineering at NC State. With a bowler hat and walking stick, Koryto takes the audience on a whimsical journey around the Randolph County farm, demonstrating how RSC will be constructed and implemented.

Koryto is part of the NC State team monitoring one of the state’s first RSC projects, completed in 2014, in a tributary to Third Fork Creek in Durham. Doll is a member of Koryto’s thesis committee.

The Durham project involves using an RSC application to fix an eroded zone washed out from stormflow erosion. The researchers are determining if the new approach can succeed in removing pollutants and infiltrating urban stormwater runoff into the groundwater, versus Doll’s application in an agricultural setting, Koryto explains.

“The applications are slightly different, but the technology is the same,” he adds.

The monitoring data from the Durham site also will provide feedback to designers, property owners and regulators considering future RSC designs in the state.

Allen notes that the project in Randolph County is one of the first DMS projects to employ the use of RSC in conjunction with pre-and post-construction monitoring. DMS aims to use the monitoring data to verify estimates of nutrient removal and track costs associated with RSC to inform future stream restoration designs.

By focusing on the two inland tributaries, researchers may establish a method of improving water quality for farmers and fishers alike.

Barbara Doll provides more information about the Durham project, including a video of the RSC installation in the Third Fork Creek tributary, in her blog post, A New Method To Restore Streams, Borrowed from Maryland, at go.ncsu.edu/dollrsc.

Janna Sasser is a communications intern with North Carolina Sea Grant. She is a senior at North Carolina State University majoring in communications, with a minor in journalism.

This article was published in the Winter 2016 issue of Coastwatch.

For contact information and reprint requests, visit ncseagrant.ncsu.edu/coastwatch/contact/.

- Categories: