ACCESSIBLE COAST: SCIENCE VIA VARIED SENSES

There is society where none intrudes,

By the deep Sea, and music in its roar:

I love not Man the less, but Nature more.

Liani Yirka shares a similarity with the early 19th century poet George Gordon, Lord Byron.

“Even as a kid, I was one of those people who would rather be surrounded by nature and animals than by other people,” she says. “I was so painfully shy they tested to see if I was deaf.”

As a result, she was determined to have a hearing impairment at an early age. “I’d sit on the playground playing with worms, anything but other kids.”

She eventually found her “niche” during high school as a volunteer junior curator at the North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences. “Finally, those were my people,” she adds.

More than a decade later, Yirka serves as the museum’s first accessibility and inclusion coordinator — and has transformed her environment into a leading example for expanding audiences.

In the five years Yirka has been on staff, the Raleigh museum has debuted technologies and programs enabling fully independent navigation for people of varying abilities. All exhibit content is available regardless of visual impairments or hearing loss.

Youth with disabilities from across the nation even swell the museum’s auditorium each year to meet professionals who share in their experiences.

“In our immediate area, these features can be useful — and are useful,” says Yirka, who received a 2016 N.C. Governor’s Award for Excellence in efficiency and innovation. “Why not, at the very least, be a training center so others can see how to implement and use them?”

Put to action, all museum visitors now are capable of experiencing science. “If our museum can help lead the way in removing a barrier, then by all means — and we have the means,” she adds.

Expanding Museum Reach

One of Yirka’s first initiatives in 2012 was to update the museum’s audio-tour system that had been in place since 2000.

To find newer and “better technology,” Yirka connected with Ed Summers, a SAS Institute software engineer and accessibility specialist who is blind. He was working to make highly visual data — such as charts, graphs and maps — accessible to people with visual impairments.

Together, the partners replaced the museum’s audio system with a mobile app that provides a multimedia guide of the exhibits. The app enables visitors with disabilities to have increased interactions with those exhibits, providing an enhanced experience for visitors who are blind, deaf or have learning disabilities, as well as the general public.

The NC NatSci app is the first of its kind, the N.C. Office of State Human Resources notes. “It’s really unique because not a lot of apps are created with the idea that people who are blind or deaf want to use them,” Yirka adds.

The software program uses a screen reader, a digital map of the museum’s exhibits, and a map of the structural aspects of the building to facilitate visitor access. Small but special features, such as including captions for all videos available with the screen reader, make the app friendly for varied users.

NC NatSci is free to download for any Apple device. The museum also provides iPod touches for visitors to use.

“Technologies like these are easily transferrable,” Yirka notes. “I would love to see this at the zoo, the aquarium, even the grocery store. I get lost finding what I need there, too.”

In 2013, innovations continued when Yirka joined with SAS and museum partners to create the STEM Career Showcase for Students with Disabilities. The first museum-based conference of its kind, it provides students interested in pursuing STEM fields the chance to meet “rock stars in their fields” who also live with disabilities, Yirka explains.

The event is designed to encourage and inspire students to pursue their science interests, regardless of obstacles.

Programs have featured Paralympians, Google engineers and astronomers. Approximately 250 students join in the free event each year, with participants coming from as far as California and Oregon. Countless others are reached online.

“We want to bring in professional role models — adults who know what it’s like and are willing to have a candid conversation about those challenges — and in the end, to say ‘I can do it, you can too,’” she adds.

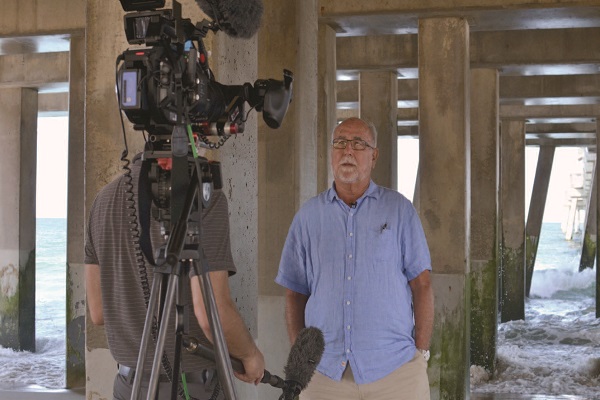

Jack Thigpen, North Carolina Sea Grant extension director, looks forward to more education programming inspired by the museum’s efforts.

“These initiatives have set a high bar,” Thigpen notes. “We look to these outstanding examples as we seek opportunities to increase accessibility and inclusion within our organization and across our national network.”

Adapting Leading Technologies

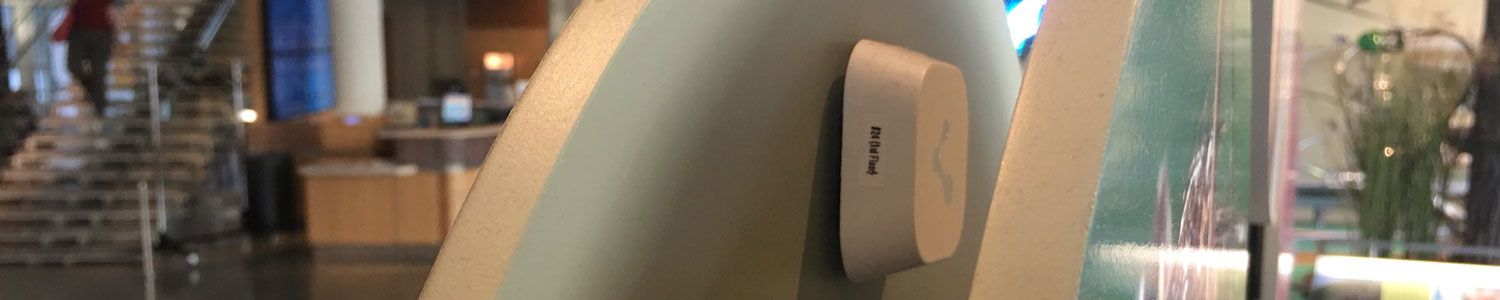

Yirka continued to broaden museum access with the 2016 debut of an indoor navigation system for people who are blind or visually impaired. The Raleigh site is the first museum worldwide to implement such a system using Bluetooth iBeacon technology, the state notes.

Combined with the GPS capability of the BlindSquare app, the beacons provide information for passive travel and building elements along the way, such as emergency exits, stairs or restrooms, Yirka explains.

Summers first encountered the beacons in the San Francisco airport when traveling with his German shepherd guide dog, Willie. Returning to Raleigh, the idea became a suggestion to aid Yirka’s goals.

Now, approximately 30 of the tiny beacons are tucked throughout the museum, giving cues as users approach. Each beacon is internally programmed to provide navigation and exhibit information, which then is voiced aloud through the phone app, guiding users turn by turn.

“Imagine going to a museum you’re not familiar with,” Yirka says. A visitor with a disability may assume a human companion is necessary to have a full experience. With the new program, however, all visitors now are able to explore on their own.

“We want to provide a level of independence,” she adds. “At the very least, providing how to get from one place to another, such as the entrance to an exhibit, or an exhibit to the elevator. We provide that in signage, but if you can’t see it, we now provide it audibly.”

Yirka hopes to extend the technology to the museum’s branch venues, including Whiteville and Prairie Ridge.

he response so far has been, “Why can’t these be everywhere?” Yirka notes. “It would be great to see it in more busy places — buses and train stations too,” she adds.

Already, the idea has drawn interest from an art museum in Charlotte. Even the town of Wellington in New Zealand is installing the technology based on the Raleigh concept.

“I try to be really down-to-earth about it,” Yirka says about working with audiences. “I’m one of you. I want to do this too.”

This article was published in the Spring 2017 issue of Coastwatch.

For contact information and reprint requests, visit ncseagrant.ncsu.edu/coastwatch/contact/.

- Categories: