SEA SCIENCE: Teaming Up with Nature to Restore Wilson Bay

Wilson Bay is a busy place these days.

Students are collecting water samples as part of a field trip to Sturgeon City, the local environmental education center. Birds are swooping to catch fish. Visitors are enjoying a sunny stroll on the nature path.

It’s hard to imagine that not long ago, there wasn’t much life in and along these waters. Over the past 20 years, a community-wide partnership has transformed Wilson Bay in Jacksonville.

No longer a polluted waterway, the bay, located in the New River Estuary, has become a vibrant wetland ecosystem and an inspiration for environmental efforts across the country.

“Communities in California, New York State and the Chesapeake Bay area have contacted me to ask about what we did to restore Wilson Bay,” says Pat Donovan-Potts, stormwater manager for the City of Jacksonville.

The change can be partly attributed to the bay’s restored coastal wetlands and oyster reefs. In this context, the habitats are examples of nature-based infrastructure intended to reintroduce valued ecosystem functions.

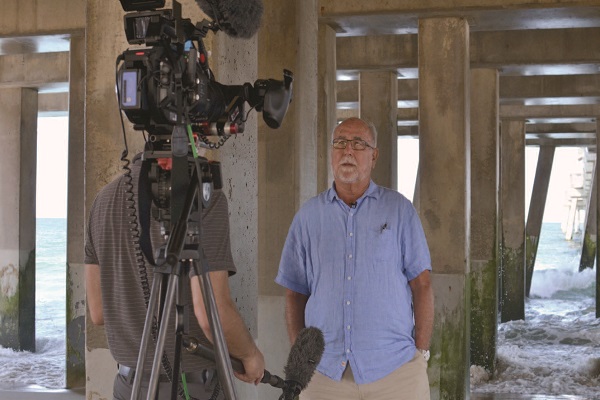

But how well does the restoration meet scientific benchmarks, and how might that change in the future? Michael Piehler, an estuarine ecologist at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill’s Institute of Marine Sciences, or UNC IMS, is leading a multidisciplinary team that is gathering new information about the restoration’s effectiveness and outlook.

“Wilson Bay’s renaissance is a remarkable success story,” Piehler says. “This project is a great opportunity to use state-of-the-art science to assess current and future impacts of the habitat restoration.”

Piehler’s partners include members from the City of Jacksonville’s Stormwater Division; N.C. Sentinel Site Cooperative, or NCSSC; NOAA National Centers for Coastal Ocean Science, also known as NCCOS; and the Department of the Navy.

This diverse group of researchers and community representatives are focused on two ecosystem functions: shoreline stabilization and nitrogen removal. They also seek to predict whether those functions can be sustained in the future, given challenges such as sea-level rise.

Their work is supported by the 2016 N.C. Community Collaborative Research Grant Program, or CCRG. Funding is provided by a partnership between North Carolina Sea Grant and the William R. Kenan, Jr. Institute for Engineering, Technology and Science at North Carolina State University. Successful projects combine scientific expertise and community knowledge.

“The CCRG opportunity was perfect since its goal is to tie communities and decision-makers with researchers to address a community-based need or concern,” says Jennifer Dorton, NCSSC coordinator.

RESTORATION BY COLLABORATION

Extensive teamwork has characterized the Wilson Bay story from the beginning. Key players have included the City of Jacksonville, NC State, U.S. Marine Corps Base Camp Lejeune, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Sturgeon City, the New River Foundation, Dixon High School in Onslow County, Coastal Carolina Community College, Carteret Community College, UNC Wilmington, and assorted state departments and programs, including the N.C. Division of Marine Fisheries, or DMF.

The New River Estuary is a brackish environment where the fresh water of the New River mixes with the salty Atlantic Ocean. In the early 1990s, the New River was in trouble. The burgeoning populations of Jacksonville and Camp Lejeune had eclipsed the capacities of local wastewater treatment plants, causing treated sewage to be discharged into the river.

The sewage contributed to the buildup of thick organic sludge that carpeted the riverbed and lowered dissolved oxygen to virtually zero. In 1995, when a hog-waste lagoon spilled into the New River, the river already was so degraded that there was no discernable impact on water quality. George Jones, then-mayor of Jacksonville, declared the city had a “moral obligation” to remediate the river.

The first step was to build a new wastewater treatment plant inland, eliminating discharge. Then, the city began restoring river habitats. Restoration was facilitated by a 1997 grant from the N.C. Clean Water Management Trust Fund. Donovan-Potts led the project, along with NC State faculty member Jay Levine and the City of Jacksonville.

It was Levine’s idea to use oysters to improve water quality. One oyster filters approximately 50 gallons of water per day. Thus, he anticipated that reintroducing the bivalves to Wilson Bay could help remove decades of organic sludge.

The plan worked. With the oysters filtering away, the water quickly cleared up. The New River was reopened to commercial and recreational uses in 2001. Since restoration began, 8.6 million oysters have been added to Wilson Bay.

As wildlife returned to the estuary, the community kept the momentum going. The old wastewater treatment plant in Wilson Bay was converted into Sturgeon City, an environmental education center and public greenspace. Jacksonville saw an increase in downtown development.

“We have a totally new city council now, and its members still support research in the New River,” says Donovan-Potts. “It’s very important that our leaders understand the importance of our environment and invest in its future.”

The restoration’s benefits to the community are obvious. The CCRG is funding research into a question that’s more complicated to answer: How are ecosystem functions responding?

ESTABLISHING THE BASELINE

Piehler and colleagues are studying shoreline stabilization. Nine acres of coastal wetlands were restored in Wilson Bay over the years. These areas dissipate wave energy, providing an ecosystem service that is particularly important during storms.

A wetland’s footprint ultimately depends on a balance between elevation and sea level. Wetland elevation can increase when sediment is delivered by tides or stormwater, or decrease due to erosion from storms or waves. Meanwhile, the average tide level is likely to increase due to sea-level rise.

Rising water levels can drown an eroding wetland, as plant communities that require dry sediment are repeatedly inundated. On the other hand, a wetland with a steady delivery of sediment might be able to match the rate of sea-level rise, maintaining its plant communities and overall area.

To determine whether Wilson Bay is keeping pace with sea-level rise, Carolyn Currin from NOAA NCCOS, Donovan-Potts and Dorton installed surface elevation tables, or SETs, in summer 2016 to measure elevation over time in the restored and natural marshes.

SETs are constructed by driving a metal pole deep underground. The pole secures a cement cylinder known as a SET mark that sits a few inches above the sediment surface.

To read a SET, scientists attach a horizontal arm with a row of vertical rods, called pins, to the SET mark. They arrange the pins flush against the ground surface and measure the pins’ height above the arm, which is rotated in a circle to survey approximately one square meter.

“NOAA personnel trained the Jacksonville team on SET reading,” Currin says. City employees read the Wilson Bay SETs in January 2017 to obtain baseline marsh-elevation data.

Over time, sediment in the wetland may accumulate or erode. By routinely measuring the pin heights and comparing them to baseline data, scientists can detect relative elevation changes in the marsh.

Sediment accumulation and sea-level rise occur at a rate of millimeters per year. Because scientists are measuring slow processes, Currin anticipates that it will take about five to seven years of data collection before they can identify trends in marsh sediment dynamics.

“The Wilson Bay SET data will be incorporated into regional and national SET inventories, which over time will provide information on how marshes in different parts of the country and in different ecological settings are keeping up with sea-level rise and erosion,” Currin says.

There are more than 70 SETs in the N.C. Sentinel Site Cooperative, a coastal monitoring network in the central part of the state. Few of those SETs are in brackish water, and the Wilson Bay SETs are the only ones located near the head of an estuary. The data will therefore help scientists identify factors that influence marsh elevation in inland estuarine settings — something that interests managers across the country.

“NCSSC has been sharing this project with NOAA headquarters and within our own network through our quarterly newsletter,” Dorton says. Donovan-Potts also spoke at the 2017 NCSSC partners meeting.

Visitors to Wilson Bay can learn more about the project from a sign that soon will be installed along the nature trail. The research will also enhance educational programs for the hundreds of school children who visit Sturgeon City each year.

“The SETs will be especially interesting for the high-school students,” Donovan-Potts notes. “We can bring them to a SET, attach the measurement apparatus and show them real science in real time. Sometimes learning is about being engaged out in the field.”

MAINTAINING WATER QUALITY

The project also is evaluating the capacity of the nature-based infrastructure to increase nitrogen removal.

Stormwater can deliver high loads of nitrogen to estuaries as it washes fertilizer and animal waste from commercial, agricultural and residential properties. Because nitrogen can fuel algal blooms that could be harmful to humans and wildlife, removing any excess is a priority. “Excess nutrient loading, and nitrogen in particular, was a significant contributor to the degradation of Wilson Bay,” Piehler explains.

Oyster reefs and coastal wetlands facilitate denitrification, a process that converts nitrogen to a gaseous form that algae cannot use to grow. Piehler wanted to determine if nature-based infrastructure increased rates of aquatic nitrogen removal in Wilson Bay.

In summer and autumn 2016, he led a field team that included Dorton, graduate students and Jacksonville employees. They collected sediment cores from restored and unrestored habitats in the wetland.

A sediment core is collected by pushing a hollow plastic tube about 10 inches into the ground, filling it halfway with a vertical sediment sample. The technique allows scientists to study the cumulative effects of microbes and invertebrates that live in the layers of sediment.

Denitrification rates were measured in the cores, which are representative of their specific habitats. All habitats demonstrated nitrogen removal under normal conditions.

Differences in denitrification were more pronounced when extra nitrogen was added to the cores to mimic the impact of stormwater. Denitrification shot up in cores from the restored marsh, whereas it remained relatively stable in cores from the unrestored areas.

“Data from the project demonstrated that the constructed marshes and oyster reefs at Wilson Bay have significant capacity to remove pulses of nitrogen through denitrification,” Piehler explains. This can help prevent algae blooms and preserve good water quality.

Increasing denitrification is a common goal for urban watersheds, including the New River Estuary. The research results suggest that nature-based infrastructure augments nitrogen removal and can be a pragmatic component of nutrient-reduction plans.

PUTTING THE PIECES TOGETHER

Overall, the CCRG will enable Piehler and his colleagues to provide new information about nature-based infrastructure in estuarine environments.

“It’s brought together people from universities and local, state and federal agencies to improve our understanding of the current contribution of nature-based infrastructure to water-quality improvement in Wilson Bay and the sustainability of these systems in the future,” Piehler says.

The results will be used by Jacksonville and nearby Camp Lejeune to inform environmental regulations, particularly regarding stormwater management. The SET monitoring program will ultimately help managers respond to elevation changes, increasing the chances of achieving restoration goals.

“The Wilson Bay project is a unique collaboration, and a great example for coastal towns,” Currin says. “It demonstrates that an enthusiastic, energetic and committed group of people can have a tremendous positive impact on the environment for present and future generations.”

It’s only fitting that looking out for the bay continues to be a cooperative effort. Wilson Bay has come a long way in the past two decades, and the community is committed to keeping the progress moving forward.

This article was published in the Spring 2017 issue of Coastwatch.

For contact information and reprint requests, visit ncseagrant.ncsu.edu/coastwatch/contact/.

- Categories: