One of my main goals as North Carolina Sea Grant’s marine aquaculture specialist is to assist in the responsible and sustainable development of the state’s growing mariculture industry. A rapidly expanding sector of this industry in North Carolina is oyster farming.

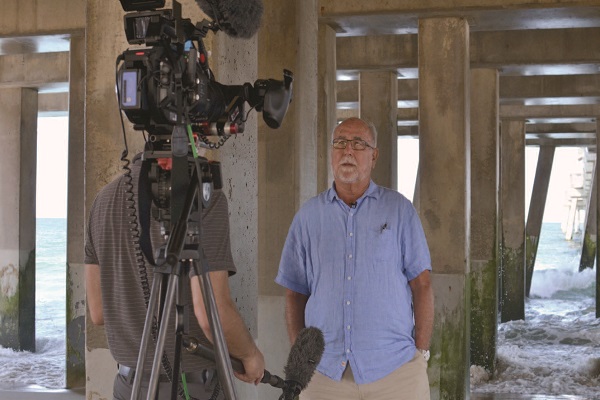

I provide support to prospective and established oyster growers, including organizing workshops for those looking to get started in the business. With every chance I get, I educate chefs, consumers and the general public about the exceptional quality of the oysters and the environmental benefits they provide.

Oysters are farmed in the wild and receive no feed input other than what Mother Nature provides in the form of microscopic algae, known as phytoplankton. While the traditional method of farming oysters is to plant seed on the bottom, more and more production is occurring in the water column, where oysters are grown in floating or suspended cages. Oysters farmed in this manner grow individually rather than in clusters, are free of grit and are uniform in size. These attributes make them highly desirable for the half-shell market.

Oysters take on various flavor profiles depending on where they are raised, similar to regional differences found in wines grown in different soils. North Carolina has an abundance of diverse coastal bodies of water with different salinities, mineral content and phytoplankton species that oysters feed on. This translates to regional variations in flavor that are sought after by chefs and consumers.

As a keystone species of the estuary — essential to the coastal ecosystem — oysters filter and clean coastal waters, and oyster farms attract all types of sea life. Growing oysters also provides jobs for coastal residents and economic benefits to coastal communities.

Although the oyster-farming industry in North Carolina is currently in the developmental stage, our state has the clean waters, interested growers, and eager chefs and consumers for such ventures to flourish. Over the past 10 years, oyster mariculture in Virginia has developed into a huge industry, with an annual farm-gate value of more than $16 million. With similar or even better natural resources, the future of oyster farming in North Carolina seems very promising.

In fact, the N.C. Division of Marine Fisheries reports encouraging numbers. In 2016, the farm-gate value of maricultured oysters was about $690,000, up 44 percent from the previous year. Production rose from 27.6 thousand bushels in 2015 to 46.3 thousand in 2016, an increase of 68 percent.

The number of water-column leases and acreage producing half-shell oysters has increased over the past six years. In 2011, there were only two water column leases and six acres in production — while in 2016, there were 41 leases and 129 acres in production.

A lot of my work involves facilitating the exchange of ideas among producers, states and researchers. My recent trip to the Oyster South Symposium in Alabama allowed me to network with oyster aquaculture specialists, researchers, oyster producers and chefs from North Carolina to Texas.

Bill Walton, extension specialist with Mississippi-Alabama Sea Grant Consortium, founded Oyster South to promote southern oysters. Walton, also on faculty at Auburn University, sought to counter the perception that southern oysters were low quality and, therefore, less desirable than those from other regions in the U.S., such as New England and the Pacific Northwest.

Through his efforts, chefs and consumers are starting to notice, request and appreciate farmed oysters from the Gulf Coast and the southeastern United States.

Five North Carolina oyster producers were at the meeting with me: Jay Styron and Jennifer Dorton of Carolina Mariculture Oysters on Cedar Island; Bill and Ryan Belter of Cape Hatteras Oyster Company in Buxton; and Ryan Bethea, who is starting up his venture, Oysters Carolina, on Harkers Island.

These growers networked with symposium participants and learned new techniques for growing and marketing their product. In addition, they showcased their oysters at the Alabama Oyster Social, which followed the symposium. Perhaps our producers enticed a few more chefs and customers to seek out North Carolina oysters.

Researchers from North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, Florida, Alabama, Mississippi and Louisiana — states attending the Oyster South conference — sought funding from the U.S. Department of Agriculture Southern Regional Aquaculture Center to determine how to prevent fouling on oyster gear.

Biofouling, a common problem for oyster producers, is the growth of aquatic plants such as algae or animals including barnacles on oyster-growing gear. Fouling can drastically restrict water flow through the gear, thereby limiting the amount of water — and therefore food — reaching the oysters.

In this two-year project, a grower from each state will use two different treatments to counter fouling on oyster culture cages: air drying and antifouling paint.

We expect the studies to start this spring. Results will provide producers with the optimal method to control fouling. These results could translate into increased production efficiency and profitability for the producers. We will share results through publications and regional workshops.

I anticipate interesting connections and results to continue to emerge from this regional focus on southern oysters — for myself and for the North Carolina growers who came with me.

This article was published in the Spring 2017 issue of Coastwatch.

For contact information and reprint requests, visit ncseagrant.ncsu.edu/coastwatch/contact/.