Ten years ago, Frank López was about to go riding around on a metal-bottomed landing craft in the middle of a lightning storm on Apalachicola Bay in Florida. The lightning wasn’t the most dangerous part. Not by far.

He’s touring the field facility and research projects along an island in Apalachicola National Estuarine Research Reserve as part of a national reserve system meeting. The air’s thick — that early summer Gulf Coast soup — and everybody’s sweating, thoroughly, as they disperse across the little island’s shoreline or investigate inland.

Without warning, mystery stirs the afternoon. The boat captain calmly but insistently starts rounding up his passengers and telling them to please hop aboard and maybe to hop aboard without delay. They really need to get back to the mainland, yes, clear across on the other side of the bay, and it wouldn’t be a bad idea if people more or less hurried.

To their credit, everybody diligently makes their way through the grasses and sand and muck. Soon the captain takes the landing craft back out onto the cobalt water, now under the sort of suddenly dark sky that only arrives in black and white films with a feverish string quartet. It’s obvious the field experiments are about to be replaced by some real-life meteorology. On cue, the storm hits in full, as if Fate had been lying in wait until the little boat had made the open water. Lightning cracks through eyelids, thunder rattles eardrums, rain whips faces.

“We’re in a metal boat in the middle of a lightning storm on a bay,” Frank López says later, very matter-of-factly. “So that was cause for a little bit of alarm.” He smiles. “And then there was the waterspout.”

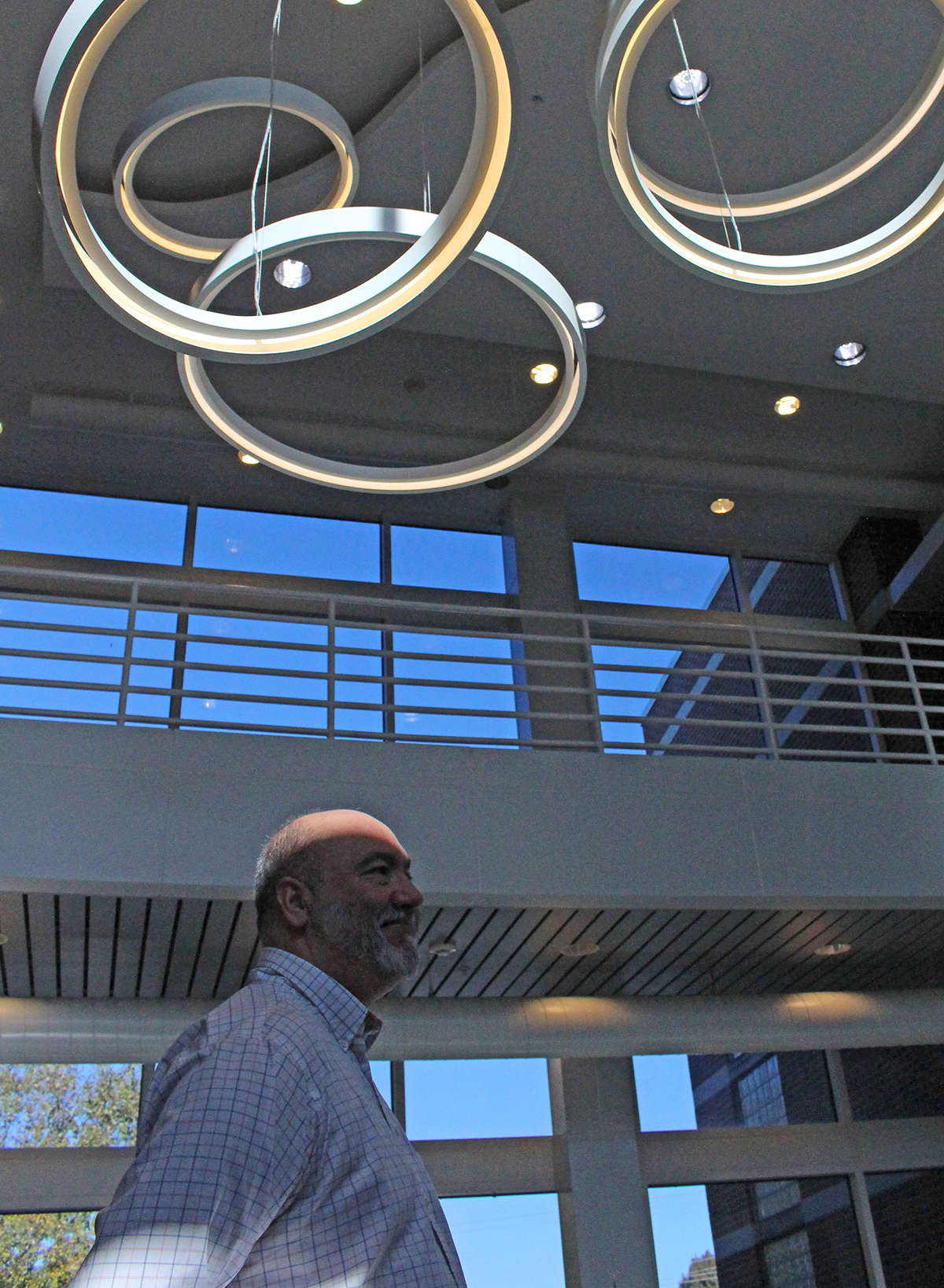

The ominous journey across Apalachicola Bay was almost exactly one decade before Frank López would become the new extension director for North Carolina Sea Grant and the state’s Water Resources Research Institute. “We’re lucky Frank made it out of Florida,” says Susan White, executive director of both programs.

In fact, anyone who has heard this story is reasonably certain Frank López should’ve been deposited over the rainbow instead of going on to head a group of specialists 10 years later who, among a long roster of other responsibilities, are helping North Carolinians plan for natural hazards. The variety of waterspouts that touch down during thunderous weather are, after all, notoriously violent. At the minimum, most people agree, Frank López might have been lucky not to have been electrocuted. Yet, Mother Nature had something even more interesting in store for him and his fellow passengers that day on Apalachicola Bay.

At the time, López was program administrator for the Old Woman Creek National Estuarine Research Reserve in Ohio, roughly 1,000 miles to the north of the bay. Some days he would kayak to work.

“It’s very small,” he says. “The National Estuarine Research Reserve System has all together over a million acres, and Old Woman Creek only has 573. But the thing that really helped us was that everything the people along Lake Erie were facing happened in our watershed, in our area.”

He capitalized on the reserve’s location, nuzzled as it is against a Great Lake, to help make Old Woman Creek a valuable pilot site for scientists and educators.

“I always liken the reserves to be a little like that movie with the baseball field cut into the corn,” he says. “Field of Dreams. You know, if you build it, they will come. We structured our research program around the premise that we could be the place where things could be learned that would be transferable to other places, too.”

The National Estuarine Research Reserve System operates as a state and federal partnership, and by design the reserves serve as field laboratories that explore estuaries and how humans affect them. As part of the Coastal Zone Management Act of 1972, coastal and Great Lakes states had opportunities to establish these marine protected areas, which today function as platforms for research and education. At Old Woman Creek, in addition to managing research and education programs — and the facilities — López regularly collaborated with decision-makers. It’s a commonality that he says serves him well at North Carolina Sea Grant and the Water Resources Research Institute.

“What bridges my role at the reserve with my new role is working directly with people who are involved in the coast and who care about its stewardship and its conservation,” he says. “That was my favorite part of that experience at the reserve, and that’s how I see myself as an extension director.”

It was also why, in the middle of his 15-year stint at Old Woman Creek, he trekked down from Ohio to Florida and out across a bay under searing sunshine to see firsthand how the Apalachicola National Estuarine Research Reserve was developing its infrastructure. How was that reserve attracting scientists and educators to its estuaries?

“I’ve always been an administrator,” he says, “but you never pass up an opportunity to get out in the field and experience it.” This was the very journey, of course, which, unbeknownst to him, would become a race against a waterspout.

The Apalachicola Reserve comprises over 12,000 acres and includes Little St. George Island, the St. Joseph Bay State Buffer Preserve, and land bordering Apalachicola Bay. Its mission includes restoring habitats, protecting rare or endangered species, and helping to maintain biodiversity in and around the bay. At one point most of the oysters that people consumed in the U.S. came out of Apalachicola Bay. The fishery has since crashed, but it was still a productive system at the time he was visiting the field site for the reserve system meeting.

“We actually had managed to get in most of the tour,” he says. “Before the storm hit.” The sun and humidity had been relentless, and although the brackish bay water exchanges out at Indian Pass and other channels, it doesn’t flush very quickly. Despite the unforgiving air, though, he had enjoyed exploring the island with his fellow visitors. It was so hot that everyone was wearing Crocs, those ubiquitous plastic-foam clogs, which, while useful on the boat, brought a specific kind of pain later. “I mean, it looked like I had foot measles — all these red dots where the holes were.”

After the captain calmly had gathered up his passengers, and after they set out on their return trip across the bay, under charcoal sky, through lightning and lashing rain, there was no way to know, of course, that one day years later Frank López would actually thank that boat captain for saving his life.

“He was a long-time outdoor educator for the reserve,” he says. “He was reading the clouds that day.”

Although lightning zigzagged and rain pelted the landing craft, as far as any of the non-Floridians aboard the boat that afternoon could tell, there weren’t any waterspouts in sight. Not yet, anyway.

In the end, it seemed almost as if Mother Nature had a plan when she spared Frank López and sent him back to Old Woman Creek. Recently, in fact, The Friends of Old Woman Creek presented him with their annual Hero Award for outstanding stewardship of the reserve over his entire tenure there. After returning from Florida, he had continued to build partnerships, and, among other successful initiatives, he developed a signature watershed program.

“Old Woman Creek is surrounded by landowners that have wanted to keep their property, and so you couldn’t really grow the boundary of the reserve,” he says. “But we were able to really get people excited locally about watersheds. There’s an element of education first, and then action second.”

His explanation of watersheds is so easily digestible it seems more like a simple reminder: No matter where you place your feet on the planet, you’re standing on a watershed. Whatever actions you take are going to have an impact on our water resources.

“From the collective standpoint, we should better collaborate to make sure we can take care of things upstream and down stream,” he explains. “There are many opportunities to do good work, and they require us sometimes to step outside of our comfort zone and collaborate with a neighbor.”

His new role as extension director for North Carolina Sea Grant and the state’s Water Resources Research Institute brings synergy that allows for a focus on entire watersheds, and, he adds, on all of the things water provides for people.

“It’s a challenge,” López says. “As a society, we haven’t always structured ourselves to succeed in these ways. Watersheds don’t necessarily correspond to political boundaries. We often have to facilitate cooperation between different entities and different communities on a watershed scale.”

At Old Woman Creek, he also helped decision-makers address stormwater management.

“Managing stormwater and making sure that waterways are healthy and that our water resources are protected is crucial,” he says. “But I’m not a stormwater expert like Sea Grant ‘s Barbara Doll, our water protection and restoration specialist. My interest is in the effect that management can have on all the parts of our natural and human systems.”

But management wasn’t even his first professional love.

“When I came to Chapel Hill for grad school my interest was in transportation,” he says. “I went to their planning school, which had a strong emphasis on coastal management and in reducing the impacts of hazards on coastal communities. Lots of people were interested in addressing coastal hazards when I was in grad school. One of my classmates described it as getting swept into a vortex.”

It’s a particularly tornadic description, considering that Frank López was almost vacuumed off a boat — and, also, that he grew up in the old heart of “Tornado Alley.”

Geographically, the famous wind-torn corridor shifted eastward with climate change after his youth. But he spent his second night on earth sleeping soundly in a storm cellar in Potter County, Texas, during a tornado warning, while hail pelted the old sheet metal door. Over the course of his childhood, he took refuge in the cellar many more times, and as a college student, he worked for a local TV crew that once filmed a Plymouth minivan spinning in a twister in Plainview, Texas.

He offers no hint at all that anything from his formative years or the episode on Apalachicola Bay might have soured him in any way to the entire topic of hazards.

“There are two primary things to think about with respect to hazards,” he says. “One is: How can you reduce people’s vulnerability before the storm? But then, knowing that storms are going to occur: How can you create conditions following storms that create a better quality of life for everyone?”

As a grad student, he learned about the North Carolina coast and issues its residents face. Through North Carolina Sea Grant, he also successfully applied to be a National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Coastal Management Fellow, which took him to South Carolina’s coastal management program.

“Then I went to Ohio,” he says, “but I kept coming down to North Carolina through the years. I always loved the state, loved the Triangle, loved the Outer Banks and the rest of the coast, and so when this opportunity opened up, it wasn’t a very difficult decision to pursue it.”

His role as extension director has involved a wide swath of work on coastal ecosystems, marine education, community resilience and many other areas, all of which he has embraced. But where better than North Carolina to apply an interest in addressing coastal hazards?

“We’ve had some really busy hurricane seasons here,” he says. “That’s the episodic threat, obviously, as we well know, especially in the wake of Florence and Matthew. We’ve also got a chronic threat that’s just not going to go away: the continuing effects of sea level rise on coastal communities. And some of the flooding that’s contributing to.”

According to López, North Carolina Sea Grant is developing better tools so that the effects of hurricanes on property and loss are not as severe. “We’ve also got some great researchers, like Casey Dietrich of NC State, who’s working on flood modeling and also on how overwash affects dune elevations.”

In addition, he touts North Carolina Sea Grant ‘s work with communities to try to reduce their vulnerabilities. “We’ve even seen some communities start to think into the future,” he says. “Nags Head, for example, where they’re starting to assess how they want to structure their community to accommodate sea level rise.”

North Carolinians are already seeing the signs.

“Some of the state’s rural folks are noticing that the seaward side of their fields are getting saltier,” he says. “Local communities are starting to deal with sunny day flooding. It’s time to think about these things now, because they ‘re not going to get better. The end of the story is that sea level rise will continue to be an issue and will probably be more so in the future. We’re helping communities think in these terms.”

Frank López will tell you he isn’t the typical candidate for a career in coastal management and a professional life that offers water no matter which direction he turns. Nor is he someone who you’d ever expect to find on a boat in a thunderstorm in the first place. Although he’s no stranger to wind, the Tornado Alley of his childhood covered much of the relatively dry, landlocked Texas Panhandle.

“You know”, he says, “it’s just amazing. When I was a kid we’d occasionally get water in the streams, but we really didn’t even have any surface water to speak of. And yet, I’ve spent most of my entire professional career working in and around water and the ocean. And coastal management has taken me a lot of neat places. I’ve been to Alaska, and they fed me just about every critter known to man, including bear. I’ve been to the Tijuana Reserve on the California-Mexico border, where their watershed lies in two different countries. Some of my absolute best travels have been to go and see some of these coastal places.”

And the trip to the reserve on Apalachicola Bay?

“That’s a memorable one,” he smiles.

Waterspout lore and waterspout science sometimes — but certainly not always — intersect. Reportedly, water-born funnels have swept up entire schools off fish and rained them on land. People often misperceive fair-weather spouts as relatively benign, and although these certainly are weaker than their land-roving counterparts, they still can be dangerous. A popular YouTube video even features a daredevil with an outboard who attempts an ill-advised “ride” on one. The viewer will have to take his word for it, because the camera inexplicably films the boat’s floorboards at the moment of truth.

However, tornadic waterspouts, which occur off-shore in tandem with thunderstorms, are less ambiguously lethal.

“So we get out on the bay,” he says, “in the middle of all this lightning. And the captain was checking the sky, and he must have anticipated that the spout was about to drop. Suddenly he veers hard to the right. I mean, all of a sudden he’s gone right full rudder. And so we all look back behind us to see what he’s swerving around, and sure enough, the bay water’s starting to froth, and then here comes a waterspout down onto the surface. It touches down on the water right there.”

While the passengers had only begun to appreciate their captain’s piloting skills, he quickly found temporary refuge for them from the storm.

“He pulled us off into a ‘crack house,” in Florida’s common vernacular of the time. “An oyster shucking house. And there we stood crammed against the wall while the water came down in buckets for about 20 minutes”.

At this point in the story, Frank López chuckles. “It gave you an appreciation of life,” he says. “When we finally got back to land, everybody made one of those I love you, man phone calls.”

But why, we might ask, didn’t that waterspout consume Frank López a decade ago? Was it luck? Fate? Piloting skill?

Consider how he describes his own career.

“You just never know”. He laughs. “That’s how I always start off when I’ m talking to young people. You can plan, but you just don’t know. You wouldn’t have guessed that when I was in high school in the Texas Panhandle I’d end up here, now, doing this.”

And consider his excitement for his new role in North Carolina.

“It’s really cool to see enthusiasm around the coastal economy and especially the buzz in our state around aquaculture and the growth of that industry,” he says. “Our program has always had a focus on helping to develop and maintain and care for industry along the coast. And there’s the potential here for doing a lot more good. We’ve got a lot of growth in North Carolina, which presents an opportunity — and presents a challenge — to do things well so that resources are sustainable. But this program is set up for continued success, and there’s an opportunity to build something even bigger here.”

And remember, too, how he described what it first was like to study hazards in graduate school, and how he, too, was swept into that “vortex.”

To add to waterspout lore: Maybe the reason Frank López wasn’t whipped off Apalachicola Bay 10 years ago was that it would have been redundant. After all, a twister had already taken him. The tornado of his own interests had already plucked him from a bone-dry county in Texas and dropped him into a career where water is everywhere.

This article was published in the Autumn 2018 issue of Coastwatch. For reprint requests, click here.

- Categories: