Menhaden: Big Questions About Little Fish

As a spotter plane for commercial fishing operations flies over nearshore waters of the Atlantic Ocean, the pilot keeps an eye on the surface below for shifting shapes like oil slicks.

When they appear, the pilot alerts the fleet that target Atlantic menhaden, or Brevoortia tyrannus, a small, silver fish in the herring family that lives in estuaries and coastal waters from north Florida to Nova Scotia. As the waters warm during the year, the species migrates north in football field-size schools, each up to 100 feet deep and pulsing with thousands of fish.

Menhaden on the Atlantic coast, combined with its sister species in the Gulf of Mexico, are among the top catch by volume for all commercial species in the United States, second only to pollock, a fish-n-chips mainstay.

Never gone fishing for menhaden? Haven’t seen it on the menu? You’re not alone. The catch is not a coveted dinner-plate item. As seafood guru Paul Greenberg discovered, “Menhaden are extremely high in omega-3 fatty acids and as such are quick to go rancid if not properly handled.” Plus, they’re chock full of bones.

Instead, whole fish typically are processed, or reduced, into fishmeal and oil and used in a range of products, including hog, poultry and aquaculture feeds, omega-3 supplements for humans, salad dressings, and dog food. The fish also are sold as bait to crabbers and lobstermen along the East Coast.

“It’s hard to believe you can catch a million fish, but nothing you can eat,” a Virginia menhaden fisherman told me.

Navigating the Numbers

For decades, menhaden was North Carolina’s number one commercial fishery by volume. From 1950 to 2004, it surpassed all other fisheries in the state, except for a few years in the late 1990s when blue crab was first. Even so, in 1997, North Carolina fishermen caught almost 100 million pounds of menhaden.

In 2005, however, the state’s only reduction facility, in Beaufort, closed its doors. In 2016, all fish caught in North Carolina waters combined amounted to less than 60 million pounds.

I have been immersed in menhaden topics the last few years. As the coastal economics specialist for North Carolina Sea Grant, I conduct economic analyses of coastal resources.

The Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission, which manages the Atlantic menhaden fishery, tasked economist John Whitehead of Appalachian State University and me with providing socioeconomic data pertaining to the fishery. The commission was in the process of updating its menhaden fishery management plan and wanted input. (Read the 2017 plan here.)

Fishery management plans rely on interdisciplinary science, including social and economic research, to help conserve fishery resources. States then implement these plans through their fishing regulations.

As part of our research, we wanted to understand how menhaden were moving through markets and how state allocations affect supply and pricing. In every East Coast state but Virginia, all menhaden caught is sold to bait markets. Virginia maintains bait and reduction fisheries.

We also set out to determine the economic impact of the menhaden reduction fishery, specifically. We focused that analysis solely on the commercial fishing sector in Northumberland County, Virginia, home to the East Coast’s remaining menhaden reduction facility.

Finally, we collected information on what the public thinks about menhaden management. Through surveys of residents in East Coast states that have menhaden fisheries, we learned whether the average person is familiar with the species in the first place, and how they would like to see it managed.

We submitted our socioeconomic analysis to the commission’s menhaden management board. Highlights from our findings follow.

Understanding Allocations

Concerns about overfishing prompted a 20 percent cut in total menhaden allocation in 2013, which affected states differently. New Jersey fishermen felt the biggest hit — their state quota dropped from 80 million pounds in 2012 to 42 million pounds in 2013. “They cut my business to less than half,” a fisherman in New Jersey told me. “Now we’re fishing eight weeks instead of five months.”

Of all East Coast states, Virginia receives the largest harvest allocation of the Atlantic menhaden catch, at nearly 80 percent. New Jersey, which supplies the majority of menhaden sold to regional markets, ranks second, at almost 11 percent.

North Carolina’s allocation meanwhile, is just shy of 1 percent. Most menhaden fishermen in this state fish directly for their own bait or sell to small recreational markets.

To better understand how harvest allocations affect the supply chain, we traced menhaden from the fishing dock to the final user.

Unsurprisingly, given their large menhaden allocations, Virginia and New Jersey supply the majority of menhaden used as bait. But we learned that these states aren’t necessarily where those bait fish are most needed.

For example, although menhaden lately have been plentiful in Maine’s waters, the state’s harvest quota has been too small the last few years to satisfy the bait needs of its fishing fleets. As a result, Maine lobstermen import menhaden from Virginia, New Jersey and elsewhere — and they pay a lot to cover shipping and storage. Shortages in other bait fisheries, like herring, contribute to the high prices.

“Bait is getting really expensive for lobstermen,” a bait dealer in Maine told our research team. “We’re buying fish out of state, out of country. We’re buying from Iceland to support our state.”

In the fall, several months after we submitted our analysis, the menhaden management board issued new menhaden allocations for the East Coast. For each state, they set a baseline quota of 0.50 percent of the total coast-wide menhaden allocation.

The change could mitigate supply bottlenecks and possibly result in lower prices in local bait markets. Indeed, buying bait from another state can easily double or triple the price. While a 0.50 percent minimum may seem paltry, for some states, the number nearly doubles their quota.

Changing Economies

Fewer commercial fishermen than ever are involved in the menhaden reduction fishery. Technological advances in the fleet and its gear have significantly reduced the labor force required, and recent cuts in the total menhaden harvest allocation for all Atlantic states have had negative impacts on the reduction fishery.

As a Virginia reduction fisherman explained to me, “When I first started fishing, when I was in a crew, it was 12 boats here. When I became a captain, there was 10 boats. There are seven now. We’re steadily dwindling down.”

Yet, while fewer people fish for menhaden, the fishery still has significant economic impact on Atlantic states, and the reduction industry plays an important role.

Our research examined the impacts of all commercial fishing in Northumberland County, Virginia, home to the sole menhaden reduction facility. We found that it contributes $78.62 million to the local economy. That figure reflects all manner of transactions related to commercial fishing, such as when a fisherman buys gear, for instance, or hires a maintenance crew for his vessel.

In other words, regulatory changes affect more than just menhaden fishermen — they impact local businesses, too. One Virginia fisherman framed the spillover effects this way: “If I took a five gallon bucket of water and dumped it right in the middle of this floor, there’s not a person in here whose feet aren’t going to get wet.”

History of Sea Chanties

Cultural anthropologist Barbara Garrity-Blake chronicled the history of menhaden fisherman in her book Fish Factory: Work and Meaning for Black and White Fishermen of the American Menhaden Industry.

The white fishing crewmembers she interviewed explained how they were “born and bred” for a life on the water, whereas the black crews expressed more ambivalence.

Garrity-Blake, now on faculty at Duke University, described how black crews sang chanteys to pass the time while working, using verse to veil their discontent:

The bitin’ spider

going ‘round bitin’ everybody,

The bitin’ spider

going ‘round bitin’ everybody,

But he didn’t bite me, Lord,

Lord, Lord, he didn’t bite me.

— LIBRARY OF CONGRESS RECORDING AFS 14,574

During Garrity-Blake’s interviews with crewman about this chantey, some men suggested that “‘bitin’ spider’ represented the captain,” while others said the image “referred to the net and the perils associated with [fishing],” which ranged from falling into the net and drowning, or pulling up an empty net.

The Public Weighs In

Our research also sought to understand how the public views tradeoffs between harvesting menhaden and leaving them to swim the sea, where they contribute important ecosystem services.

We surveyed Atlantic Coast residents to understand how they rank the importance of commercial fishing jobs, the health of game fish and water bird populations, and water quality.

We also asked respondents for their opinions on an ecosystem-based approach to managing menhaden, which would account for the species’ role as prey for fish, water birds and marine mammals. Such an approach would allow fishery managers to consider the harvest of menhaden within a broad ecosystem context.

About half of the individuals we surveyed knew nothing about menhaden before taking the survey. We provided all survey respondents with some basic information about the species and its role in the ecosystem, as well as in commercial fishing. With that information in hand, they gave their opinions about how the fishery should be managed.

Most respondents said that menhaden’s most valuable commercial use is fish oil. As for menhaden’s most important ecological role, respondents cited improvement of water quality.

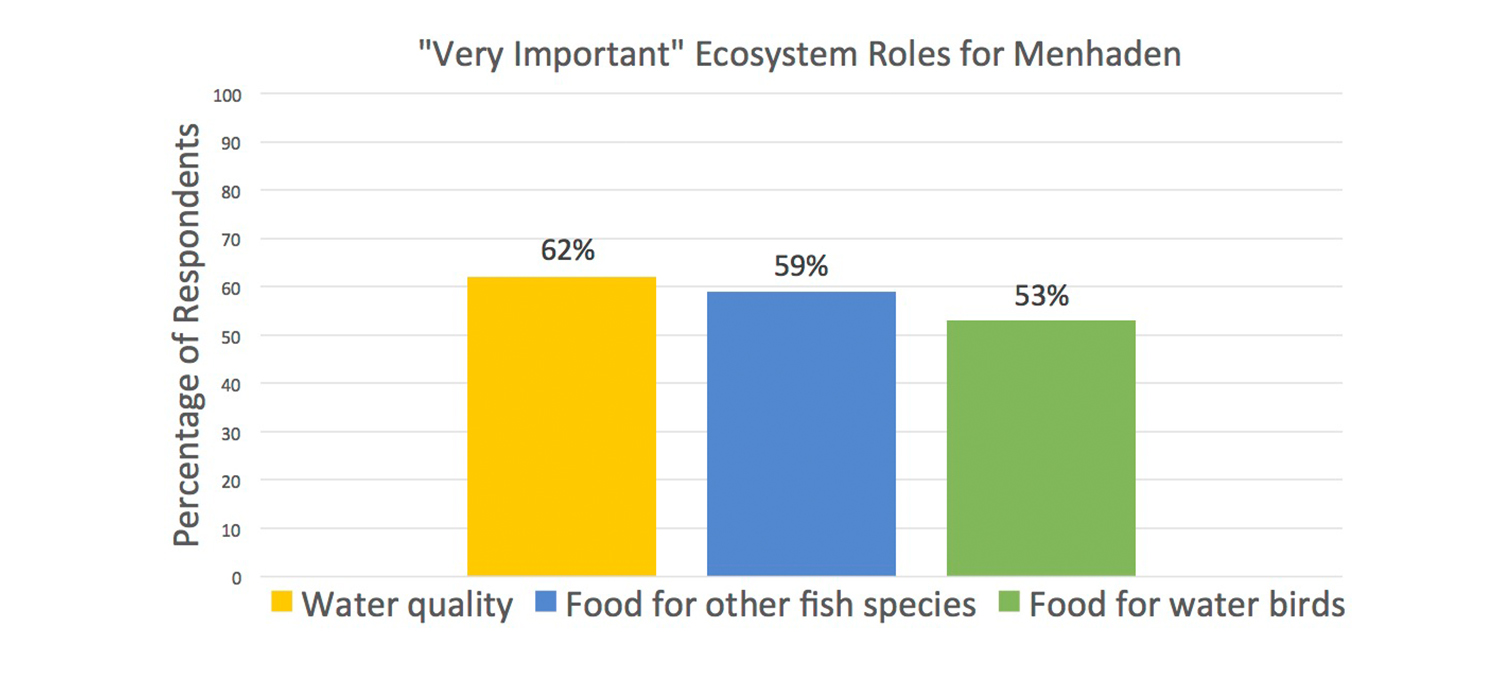

Figure 1 shows the percentage of respondents who thought a given ecosystem use was “very important.”

The extent to which menhaden, a filter-feeding species, contributes to water quality is subject to scientific debate. Recent research conducted by the Virginia Institute of Marine Sciences suggests that filter feeding by menhaden has little net effect on overall water quality in the Chesapeake Bay, a major spawning area for the fish.

Some environmental advocacy groups have argued that, because menhaden consume phytoplankton,

they play a vital role in cleaning up unwanted algae blooms, but that relationship demands further study.

Almost 60 percent of respondents said that menhaden serve a “very important” use as food for other fish. Just over 50 percent said menhaden are “very important” to water birds’ diets. In fact, menhaden’s role as a forage fish is well documented. The species attracts predators including striped bass, humpback whales and osprey, among others.

As a fishery, menhaden currently are neither overfished nor experiencing overfishing, according to the Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission. When we asked respondents whether the total harvest allocation of menhaden should be increased, about 80 percent supported a boost in quotas.

At the end of 2017, the menhaden management board voted to increase the total menhaden harvest allocation for the Atlantic Coast by 8 percent, to 216,000 tons. At the same time, they reduced menhaden catch in one particular jurisdiction — the Chesapeake Bay, an important nursery ground — by 42 percent, to 51,000 metric tons.

Commission members will continue to discuss the role that menhaden play in the environment. As they move toward an ecosystem-based approach to management, they’ll have to balance diverse societal needs. Those debates won’t make allocation and state quota decisions any easier.

To learn more about our research, you can access the socioeconomic analysis via the Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission’s webpage for Atlantic menhaden. Scroll down to the Press Releases section and click on “ASMFC Releases Atlantic Menhaden Socioeconomic Report.” A link to our report can be found found in the news release.

Views from the Field

The socioeconomic analysis of menhaden management required significant field work, data collection and analysis. Our research assistants on the project, all NC State University alumni or graduate students, discuss their key takeaway from the menhaden project and its role in their current work:

• Brendan Adams, now Grants Administrator, NC State Parks

“I interviewed fishermen up and down the East Coast, and through that, better understand the need for community involvement and engagement in the fishery policy process. Many of the individuals I spoke with felt like their voices were not heard and that ‘top-down’ policy changes affected them negatively. I felt like it was important to listen to their perspectives and summarize for policymakers’ consideration.”

• Alexandra Naumenko, now Ph.D. Candidate in Agricultural and Resource Economics, NCStateUniversity

“In administering the public survey, I gained insight into their perception of menhaden policy and its impacts. I was pleasantly surprised that the results represented the general public across the Atlantic states and every demographic, not just key players, like the fishermen and environmental groups. I became confident that if the public is informed about menhaden, they could play a key role in sustaining the fishery.”

• Andreanne Meley, now Chain of Custody Coordinator/Lead Auditor, Rainforest Alliance

“I helped to conduct interviews and analyze the data. In my current work, my clients [forest landowners] are like the menhaden fishermen. They are all affected differently by forest industry certification standards. The menhaden work taught me how to keep an open mind when discussing the issues they are witnessing in the forest products sector.”

- Categories: