The Steeples area. The Lophelia Reefs.

Can’t place these exotic locations off the Carolina coast? Just ask countless teachers and students who followed the “Islands in the Stream 2002” research expedition through online logs.

The daily journals often reflect the excitement of twice-daily submersible dives. But there’s much more to these missions that are sponsored by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Ocean Exploration program.

“We work the whole water column,” says Steve W. Ross of the N.C. National Estuarine Research Reserve, leader of the team that designed the second leg of the three-part voyage. “The sub is just one piece of gear we use — and it is more vulnerable to weather,” he adds with a knowing nod.

When the weather cooperates, the sub provides spectacular views of deep-water habitats, as it can drop to 3,000 feet below the surface. But to find The Steeples off North Carolina’s southern coast, the sub had to dive less than 400 feet, four times deeper than most scuba divers venture.

The Steeples area includes large, irregular boulders and ledges — pieces of the continental shelf broken off by erosion and geological events and scattered by storm currents, the scientists explain. The warm Gulf Stream current transports fish larvae and encourages a dominance of tropical reef fishes.

During an expedition in 2001, researchers reported sightings of several fishes that were previously not found north of Florida, several fishes new to the United States, and many species thought to be rare — thus prompting the return visit.

“This dive added another up-close and personal look at this fauna, and new information on the overall community that supports an important food fishery,” says Ken Sulak of the U.S. Geological Survey.

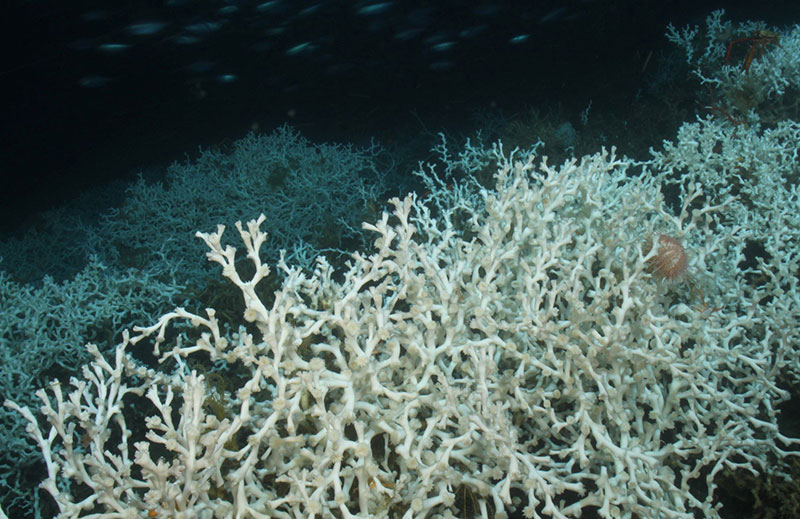

In the 2002 voyage, the scientists also revealed secrets of the Lophelia Reefs, located in much deeper waters, about 80 nautical miles south of the team’s study sites at an area off Cape Hatteras known as “The Point.”

“These are not the familiar colorful corals of shallow reefs, but are very slow-growing stony corals adapted to life in dark, cold waters. They lack the light-dependent symbiotic algae that impart color to reef-building corals in tropical seas,” explain Sulak and Ross.

While they are delicate, the corals can live 1,000 years or more. “Together, the ridges and reef mounds, which may rise as much as 150 meters from the surrounding substrate, act to accelerate bottom currents — a condition favorable to species that filter-feed on current-borne plankton,” the scientists add.

A Working Cruise

The days are long for the 19 researchers plus crew aboard the R/V Seward Johnson and its submersible vessel the Johnson Sea-Link II, which are based at Harbor Branch Oceanographic Institution in Florida.

The schedule for this particular mission is set by Ross and Sulak, as well as Liz Baird of the N.C. Museum of Natural Sciences and Fritz Rodhe of the N.C. Division of Marine Fisheries. Their team includes graduate students and Alan Felker, a seventh-grade teacher from Boone who also teaches at Appalachian State University.

Aboard ship, data are collected and analyzed in four shifts. For example, Felker works from midnight to 6 a.m. and again from noon to 6 p.m. The work not only enhances his knowledge, but also allows him to be a role model for his students.

“Through activities such as this expedition, we hope students will see the large variety of occupations that the scientific community offers,” Felker adds.

While in the compact submersible, the scientists use sophisticated still and video cameras to record activity. They also audio-tape personal observations.

“That is why you are there — to accurately extract information,” Ross explains. “Video is a great permanent archive of the animal’s behavior.”

Back in the shipboard lab, the team reviews the videos and selects clips to place on the Internet.

In addition to the cameras, the sub has a collection system that allows researchers to fill up to 12 buckets during each dive. Meanwhile, a variety of sampling gear is used throughout the day and night — surface trawls that reveal the Sargassum communities, otter trawls or tucker trawls that work at varying depths, even a small “sled” to take benthic samples.

Specimens vary. The bounty may include a Porpida, which has tentacles and is related to the jellyfish. Another catch includes hundreds of brittle stars.

“Every time we put a piece of equipment in the sea, we learn something new,” says Baird, who daily would review e-mail questions sent by students of all ages.

“They ask questions directly related to our experiences the previous day,” she adds.

A Different Perspective

Traditionally, fisheries stock assessments have utilized models that draw upon data gathered through trawling samples. But in many locations, the high-profile reefs prevent research trawling. “If they can’t trawl, they can’t get fish counts in these habitats,” Ross says.

That means the submersible trips offer the only sampling possibilities for certain areas. But the scientists are after more than fish counts. They are looking at the ecology, community structure, food chain relationships and other factors. “Who’s eating whom? Where does the food come from?” Ross questions.

One of the research projects compares observations from the submersible to the catches reported by a commercial fishing boat, the Amy Marie, working with the team in The Steeples area.

“Indeed, we saw many of the same top predators, including yellowmouth grouper, red snapper, vermilion snapper, scamp and porgy, that typically wind up in the local fish markets. But through the eye of the submersible, we saw much more,” Sulak says of the dives where 50 or more species were recorded.

Comparison of trawl and submersible data is part of a project funded by the N.C. Fishery Resource Grant Program, which encourages partnerships between the commercial fishing and academic communities.

Such individual projects within the overall expedition have specific research goals, but the data and observations often fit into larger policy issues — such as selecting Marine Protected Areas or identifying essential fish habitats.

From Sea To School

While researchers are studying schools of fish, schools full of children eagerly follow research cruises via the Internet.

Paula Keener-Chavis, education coordinator of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration, is working with the National Undersea Research Center at the University of North Carolina at Wilmington, the N.C. Aquarium at Fort Fisher, North Carolina Sea Grant and other agencies to help teachers take undersea lessons into more classrooms.

During Islands in the Stream, educators gathered at UNC-W to learn more about the expedition and even chat with the scientists onboard, thanks to satellite phone technology.

“This is an exciting new initiative for marine education,” says Lundie Spence, former North Carolina Sea Grant marine educator, who now directs the Southeast Center for Ocean Science Education Excellence.

“The Ocean Exploration missions have a mandate to spend 10 percent of funding on education, so this is a significant opportunity for North Carolina schools to get new, lively yet relevant content and materials,” adds Andrew Shepard, NURC associate director.

Flo Gullickson, a Guilford County high school teacher, says lessons such as “All That Glitters” — which explains bioluminescence — fit her courses. “It is very impressive to see how visible light enters the deep ocean and why animals have certain colorations.”

Students in her classroom begin to understand the underwater experience that takes the breath away from even a veteran marine educator.

Baird saw the light effects on her first dive in the sub — down 2,900 feet at The Point.

“We saw just a few fish, but there were lots of amazing shrimp with long flowing antennae. The bioluminescence was incredible. It was like being in a glowing snowstorm,” she says. “I love being at sea.”

This article was published in the Spring 2003 issue of Coastwatch.

For contact information and reprint requests, visit ncseagrant.ncsu.edu/coastwatch/contact/.

- Categories: