SEA SCIENCE: Recreational Science: Drumming Up Fishery Conservation

To many weekend anglers, getting paid to catch, tag and track fish might sound like the perfect job. Might that is, if you don’t consider getting caught in afternoon thunderstorms, being tormented by greenhead flies and mosquitoes, or having the hunt disrupted by hurricanes.

In a two-year research project funded by the N.C. Fishery Resource Grant Program (FRG), George Beckwith of Down East Guide Service in Oriental, and co-researcher Rob Aguilar endured pests and foul weather to learn about post-hooking mortality in red drum. Despite it all, Beckwith remains so enthusiastic about the study — which he describes as groundbreaking — that he reapplied to FRG and is taking on another year of study.

FRG provides funding to people involved in recreational or commercial fishing industries who have good ideas for protecting or improving fishery resources. As a guide and charter boat captain, Beckwith was concerned about using the best gear to increase survival of the red drum caught and released by his clients in the Neuse River and Pamlico Sound estuary.

He teamed with Aguilar, a graduate student at North Carolina State University, and Peter Rand, assistant professor of zoology at NC State, to design and carry out the study. They primarily looked at survival rates between 16/0 circle hooks and 7/0 J-type hooks.

Circle hooks, according to Jim Bahen, fisheries specialist with North Carolina Sea Grant, were first used by Japanese long-liners to catch tuna. They have gained popularity in catch-andrelease industries because they tend to hook less deeply than J-hooks, presumably resulting in less hooking trauma and lower mortalities in released fish.

Bahen agrees with Beckwith that the project is, indeed, “groundbreaking” both in its use of sonic tagging of red drum and in the information gleaned from data collected in the study. Bahen sits with Beckwith and others on the red drum advisory panel for the N.C. Division of Marine Fisheries (DMF). “The division was looking at requiring certain types of gear but didn’t have enough information about hooking mortality,” Bahen says. And, as often happens with FRG studies, he adds, more was learned than was expected.

“The incidental information from the original study about the movement of red drum gave scientists a whole new perspective on the life history and biology, as well as factors such as salinity and water temperature that cause the fish to move,” explains Bahen.

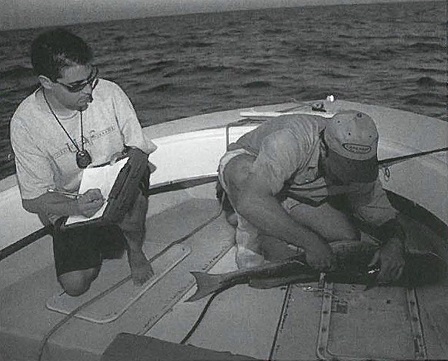

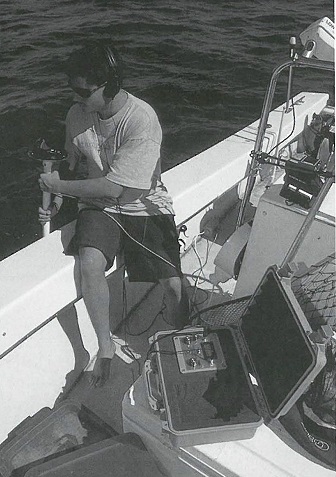

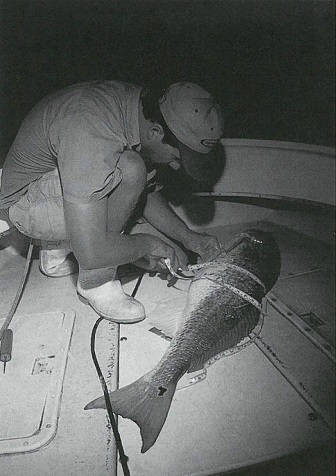

In Beckwith’s study, red drum caught with both hook types were tagged with ultrasonic transmitters that emitted unique pulse-signals. Fish were tracked for 72 hours using headphones attached to a submerged signal detector. Beckwith, who has a bachelor’s degree in marine biology from the University of North Carolina at Wilmington, says that fish are assumed to have survived if still alive after 72 hours.

Beckwith typically removes all hooks, regardless of the piercing location of the hook, to increase chances of survival. For the study, however, deep hooks were left in place to more closely mimic the actual practice of most recreational anglers. The teeth in the rear of the mouth of these large fish can be a deterrent to deep hook removal.

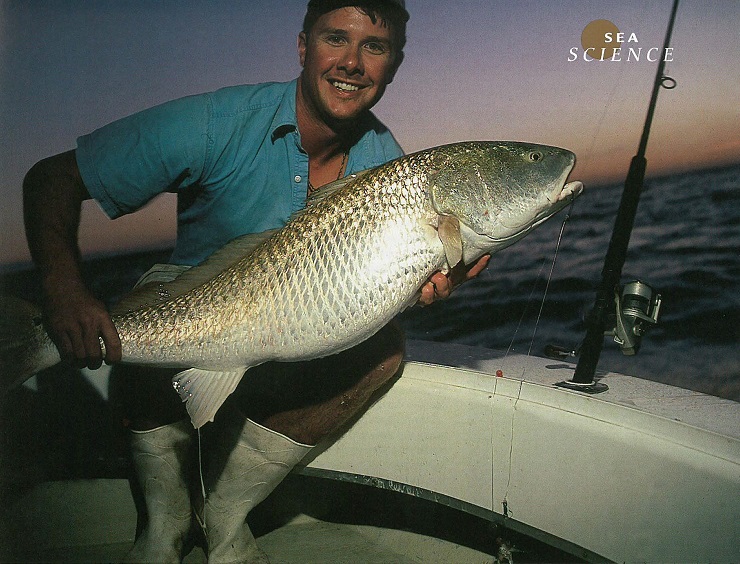

And we are talking about big fish.

“North Carolina is renowned for large red drum. In fact, the largest and oldest are caught off our coast,” says Lee Paramore, lead red drum biologist for DMF. The largest on record, he says, weighed 94 pounds, 2 ounces and was caught in the surf off of Avon.

So popular is the red drum here that it has the distinction of being the state saltwater fish. But North Carolina is not the only place where the red drum is sought.

It is also the star of the once ubiquitous Louisiana-style blackened redfish. In 1984, The Silver Palate Good Times Cookbook referred to this as “an increasingly popular dish.” Fortunately the authors listed red snapper as an alternative because — although not known at the time — the fate of the red drum was becoming more and more precarious.

By the time the first stock assessments were done in the early 1990s, the red drum was deemed “overfished,” according to Paramore.

The status of a fish population is based on its spawning potential ratio. This means, says Paramore, that “there are not enough fish surviving to the age of maturity to sustain a healthy population.”

Recreational anglers can keep only one red drum per day, according to current state regulations, and the fish must be between 18 and 27 inches. While this represents the size of the — biologically-speaking — vulnerable juveniles, it also represents the best size for eating, says Beckwith.

The regulation is designed, says Paramore, to limit the number of juveniles that can be removed from the population. There is no targeted commercial fishery for red drum, although a very limited number can be harvested as bycatch.

Some states have gone further, initiating net bans to protect overfished species, including red drum. But Beckwith says he believes North Carolina is doing a good job protecting red drum without undue regulations on any one fishing group.

Given the antipathy that can exist between recreational and commercial fishing groups, Beckwith says his position makes him an “oddball.”

“I have a lot of sympathy to, and ties with, commercial fishermen. I’m sympathetic to their plight,” he says. “I think there’s enough room for all of us.”

Beckwith’s goal, with his FRG project, is to find ways for recreational anglers to fish “in a less destructive manner.”

The first year of the study, 1999, was interrupted by flooding from hurricanes Dennis and Floyd. Too few red drum were located after the flooding for that data to be included in the final analysis. In 2000, 22 red drum were caught, tagged and tracked. The only death noted involved a 7/0 J-hook that deeply pierced the fish. The time that red drum was handled out of water was similar to others that survived, and so was not considered a factor in the death.

From over 200 fish caught during the two-year study, only 10 percent of fish caught with circle hooks were deeply pierced compared to around 50 percent caught with J-hooks. Deep hooking can cause bleeding, anatomical damage and stress from the additional time required for hook removal.

And although Beckwith prefers removing all hooks, he says data don’t prove that leaving deep hooks in place is more harmful. ‘The hooks can be encapsulated or expelled without harm,” he says. The fish “probably get poked and prodded a lot,” he says, given their “diet of hard crabs, which they crush and swallow whole.”

The verdict is still out on which hook performs best with minimal damage, according to the final report for the project, because the total number of samples was low. But with data gathering continuing, and barring any more natural disasters, answers should be forthcoming.

Beckwith says he has already been surprised by some of his findings about red drum behavior. He expected, based on his fishing experience, to find the same fish with the same group each day. “There’s not a distinctive school of fish,” he says, explaining that he found a lot of random mixing within groups.

Rand notes the significance of red drum movement. “Our longer term tracking data suggest fish are swimming parallel to shore, and repeatedly moving upstream and downstream as far as 10 kilometers,” he explains. “They don’t stay put, which was the conventional wisdom of anglers.”

Red drum movement is more than a curiosity — it could have important management implications. Rand explains:

“The thought is that these fish move out through the inlet and onto the continental shelf to spawn in the fall. However, the fish we caught for our study in the mouth of the Neuse River and in the sound appear to be ripe and ready to spawn. The patterns of movements we have observed may be related to courtship. We need to clearly identify critical spawning habitat if we’re going to try to manage this fishery responsibly and restore the population to a healthy condition.”

Beckwith is optimistic about the fate of the red drum. “I think there might be a lot more out there than we realize. It’s only a matter of time, with the regulations we’ve got in place, until we get on the right track.”

A bookmark-size, waterproof red drum information card is available from North Carolina Sea Grant. The card details catch limits, use of circle hooks and interesting facts about the state’s saltwater fish. For a free sample card, call North Carolina Sea Grant at 919- 515-2454 and ask for publication UNC-SG-00-05. For bulk orders, cards are 50 cents each.

This article was published in the Autumn 2001 issue of Coastwatch.

For contact information and reprint requests, visit ncseagrant.ncsu.edu/coastwatch/contact/.

- Categories: