Small City, Big Plans

From U.S. 264, Washington, North Carolina, looks like any other city or town — car dealers, gas stations and a few restaurants line the strip, all set back from the roadway with plenty of parking. But turn the corner onto Market Street, near the old fire station, and you will find one of the most up-and-coming places in eastern North Carolina.

“Little Washington,” as locals say, is a small city with big plans for its future. City leaders want to keep the historic downtown hopping by luring more businesses, tourists and residents with innovative land-use and development plans, tax credits and grant programs.

“Our historic district sort of transcends time because we have a different flavor of the periods in history, which is really unique,” says Bobby Roberson, Washington’s director of planning and development.

Revolutionary and Civil war era buildings hosting a range of specialty shops mingle with more contemporary structures. Streets lined with leafy trees and Central Park-style benches invite pedestrians to sit for a moment and drink in Washington’s historical but hip charm.

The eclectic character of downtown stems not only from the mix of architecture but also from the city’s focus on “smart growth” development principles, which encourage walkable communities with a mix of housing, retail and open spaces.

“I live downtown, upstairs in one of the buildings, and I love it,” says Joey Toler, head of the Washington Arts Council. Toler’s building is a perfect example of “mixed-use” development. The first floor contains retail space, while condos or apartments are located upstairs. “I can walk to work, I can walk anywhere downtown,” he says.

Only about 13,000 people live in Washington, yet the city boasts small town shops like hardware and furniture stores alongside niche merchants — including a gourmet wine shop, cigar store and art gallery — usually found in larger cities. But as new businesses take hold, some existing ones perish.

“We’ve lost things like five-and-dime stores, like the Woolworth’s,” says Penny Rodman, a 77-year-old Washington native. “We do miss some of the small mom-and-pop shops that have gone, but we’re getting some of those back, and that’s a change I’m delighted to see,” she adds.

Colorful awnings and tidy, quaint storefronts dot Main Street, thanks to the city’s side grant improvement programs.

“Basically, if you can spend $4,000 to fix up the front of your business, we’ll give you $2,000 back,” Roberson says of the side grant program. “The city is committed to helping the central business district, and I think the side grant improvement has really helped the visual quality of the business downtown.”

A stop into Down on Main Street, a casual dining restaurant on Main Street between Union and North Market Streets, demonstrates that Washington appeals to most anyone. The Friday afternoon lunch crowd in the renovated building includes senior citizens, young and middle-aged professionals, college students, couples and young families.

“Washington is really nice because it’s a community where I can get mostly everything I want,” says Becca LaViolette, a tourist having lunch with her husband, Ernie. “It has all the little restaurants and shops you could want, and they all have their own personality.”

CURING MAIN STREET MALADIES

Downtown Washington wasn’t always this picturesque.

Two devastating fires destroyed the city and its historical structures in the 19th and early 20th centuries. Federal troops set the first fire during the Civil War, and a second fire swept the downtown in 1900. Washington rebuilt, and for nearly a century the city was a major commercial and cultural center because of its location on the Pamlico River.

But, like many small cities and towns across America, Washington experienced an economic downturn during the “strip mall era” of the late 1960s and 1970s, when businesses vacated traditional downtowns for new shopping plazas on the outskirts of communities.

“Washington Square Mall developed on 15th Street, and many businesses left,” Roberson says.

“We lost some locally owned businesses that I’m sure are lamented,” adds Tony Lotta, a retired teacher from Ohio who moved to Washington in the 1980s. One example is the local Belk department store, which now sits vacant on Main Street.

As the downtown economy deteriorated, so did Washington’s landscape of historic homes and buildings. Many were being torn down and replaced with modern buildings, much to the dismay of the community.

Residents took their concerns to the town council, which authorized then-planning director Marvin Davis to start developing the “historic district,” in a manner that both preserved the town’s heritage and let it prosper.

Over the years, city leaders have juggled a handful of development plans from outside consultants, drawing out key elements from each. An earlier strategy, known as the “Renaissance Plan,” provided local leaders with an implementation plan for downtown improvement projects.

“We always picked some project to do every year over an eight-year period,” Roberson explains. “Plans look great, but taxpayers start to have some question marks about spending additional taxpayer dollars for another [improvement] plan if you didn’t implement the plan you had five years ago.”

The latest downtown revitalization strategy came in 2005 from WK Dickson, a group of community infrastructure consultants headquartered in Charlotte. The highlight of the Dickson plan is the continued implementation of core “Smart Growth” principles, including enhancing connectivity between downtown and the waterfront, creating more open space and physical infrastructure for festivals and the arts, and increasing commercial and recreational activities along the waterfront.

“It’s a malleable strategy,” says Toler, who also is interim director of Downtown Washington on the Waterfront, a local organization dedicated to restoring and renewing the historic waterfront district.” We may look up 10 years from now and see that some situations are different.”

One of the city’s first projects under the Renaissance Plan was to narrow and reduce parking on the Stewart Parkway, the main artery of the town that runs through the waterfront area, near the historic central business district. The next step was to bring traffic back downtown, Roberson says.

In the late 1970s, the city renovated the old Atlantic Coastline Railroad Depot into a civic center, which also houses the Washington Arts Council. The depot retains several features from its railroad roots, and is popular with everyone in Washington, Toler says.

“If s open to the public and it’s used for everything from high school proms, to conferences, to wedding receptions — I’ve even seen funerals in there,” he says. “It’s truly a multipurpose space.”

RECREATING A CITY CENTER

While the depot brought in traffic from the west side, there was nothing to generate it from the east side, Roberson says.

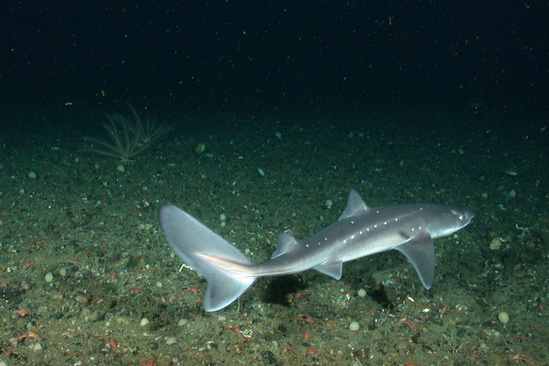

Enter the North Carolina Estuarium, an educational center that spotlights the importance of the state’s coastal rivers and sounds. Built nearly a decade ago by the city and a nonprofit called Partnership for the Sounds, the Estuarium draws visitors and school groups from all over eastern North Carolina.

In 1998, Washington purchased 13 acres of land near the Estuarium, eight of which were sold to a developer. Today these riverview condominiums and townhomes start at $400,000. With the help of a $4.2 million grant from North Carolina’s Clean Water Management Trust Fund (CWMTF), the city turned the remaining five acres into a wetland to improve stormwater drainage.

When the city wanted to do some additional paving downtown, they were mindful of the Pamlico-Tar River Rules, based on the N.C. Division of Water Quality’s plan to keep excess nutrients in stormwater run-off from polluting the Pamlico River.

“We talked to the Pamlico-Tar River Foundation and did a joint-venture project to actually take all the stormwater in the central business district and divert all that to the other side of the Estuarium on that five acres,” Roberson explains.

The city provided an additional $2 million for the project, and $500,000 came from the N.C. Division of Coastal Management. The city then linked the civic center and the Estuarium with a walkway next to the river.

“People are on the boardwalk from dawn until midnight,” adds Toler. “It’s an amazing draw.”

“It’s encouraging to see this coastal community planning for water quality protection while they are revitalizing their downtown,” says Gloria Putnam, water quality planning specialist for North Carolina Sea Grant. “This is an example of how good environmental planning is being coupled with economic development.”

East of the Estuarium is a half-acre of property that once belonged to Evans Seafood Company. Owned by the city since the late 1990s, the city council has debated about what to do with it for years, says Lee Padrick, chief planner for the state’s Division of Community Assistance.

City officials are entertaining proposals to build a hotel on the site, as long as the adjacent open space would be preserved as a conservation easement or other green space.

“The city council has done a good job of getting public input about this and other projects before moving forward,” Padrick notes.

Another hot topic in Washington is a proposed public mooring field in the Pamlico River, between the Norfolk Southern Railroad trestle and the U.S. 17 bridge. Some locals floated the idea at a public meeting last fall, according to Padrick.

“These residents see Washington developing, and they see public mooring fields in tourist destinations like Florida and think it might bring people here,” he says.

A subcommittee was formed to begin exploring the possible costs, environmental impacts and regulatory requirements involved in mooring fields, Roberson says. As of June, the subcommittee had not met or made any recommendations to the planning board.

A mooring field would be completely new territory for Washington, Padrick adds. The only other town in North Carolina even considering one is Carolina Beach. The state has very few regulations about mooring fields. A detailed harbor management plan would be necessary to preserve the river’s environmental integrity, he adds.

DOWNTOWN DRAMA

Despite the growth, the city is still missing an “anchor attraction” or “something that would draw people into the businesses and restaurants in the city center,” Roberson says.

The answer lies with the Turnage Theater on Main Street, between Market Street and Union Drive. Once a vaudeville theater upstairs and retail space downstairs, the Turnage became a motion picture theater in the 1930s. It closed in the 1980s and was abandoned, becoming a rotting eyesore for the community.

“Rust never sleeps,” says John Vogt, executive director of the Turnage Theater Foundation, Inc., a nonprofit organization dedicated to renovating and running the theater. “A small leak developed into a larger leak, plaster started falling, birds moved into the building, as did other varmints, wild cats — you name it.”

The city was going to tear down the derelict theater until some concerned citizens raised enough money to purchase it 12 years ago. Through a combination of private money and grants, the group is renovating the Turnage into a state-of-the-art, live performance theater that highlights its history.

“This is not a restoration of the theater, this is a rehabilitation of the old building,” Vogt emphasizes. “We’re putting in all new electrical [systems], all new plumbing, all new air conditioning, new seats, everything.”

Vogt and his crew are even adding a new section to the building’s rear, which will house larger bathrooms and dressing rooms, as well as a loading dock. Workers are restoring some plasterwork and decorative elements, such as the intricate details on the theater’s ceiling, around the stage’s presidium arch, and on ironwork in the foyer and railings leading to the balcony seats.

“Essentially, we [will] have a new, contemporary building with historic elements,” Vogt says.

The fake opera boxes on either side of the stage, once decoration, will become areas for additional lighting and acting. The crew also dug up an old orchestra pit, cemented over when movies with live music went the way of silent movie stars.

The Turnage Theater Foundation will run the 400-seat facility as a regional performing arts center hosting community and traveling shows, according to Vogt. The foundation also is working with East Carolina University’s School of Theatre and Dance to use the Turnage as a venue for summer stock theater and other productions.

The grand opening for the 1930s theater is scheduled for Nov. 3. Renovation of the vaudeville theater upstairs is “Phase II” and will begin once funding is secured, Vogt says.

“A lot of people are waiting for us to open because they think we’re going to generate traffic.”

HOMETOWN DESTINATION

More people downtown is what the city wants, Roberson notes. And, the newly renovated Turnage will be a perfect complement to the city’s thriving art and music community, Toler adds.

Washington already hosts two major art and music festivals each year: the East Carolina Wildlife Arts Festival in February, and Music in the Streets, which features North Carolina bands downtown from April through October.

Recently, with the help of the Beaufort County Arts Council and the Pine Needle Garden Club, the city sponsored the “Crabs on the Move” public art project. Local artists painted blue crab statues now on display throughout downtown.

Across the street from the Turnage are the remains of the old Belk department store. Its boarded windows are starting to look out of place.

“We’ve got investors down here buying buildings all the time,” Vogt says. It is only a matter of time before an entrepreneur gives the former department store a makeover similar to its neighbors, he suggests.

That’s fine by Roberson, as such revitalization efforts will continue making Washington a desirable place to live and visit. Locals, like Rodman and Lotta, say they like what’s happening downtown, and hope the city continues its course.

“I’m very glad to see things making progress,” says Rodman, who says she’d like to see the city refurbish the old carriageways between buildings into beautiful garden walkways that lead to the shops on Main Street.

Inquiries from prospective homebuyers are a regular occurrence, says Lynn Lewis, the city’s tourism center. Many are out-of-state retirees or residents of Greenville looking for a small town atmosphere with some big city amenities.

Rodman understands. After marrying a “local boy” and traveling with him to 14 different countries for more than 35 years as part of the diplomatic service, “we couldn’t wait to get back to Washington, North Carolina,” she says.

“I wouldn’t trade anything for a wonderful, small hometown.”

To learn more about visiting Washington, go to: http://www.littlewashingtonnc.com/.

This article was published in the High Season 2007 issue of Coastwatch.

For contact information and reprint requests, visit ncseagrant.ncsu.edu/coastwatch/contact/.

- Categories: