Climate Change in the Napa Valley of Oysters

Global Warming and NC’s Most Important Shellfish

Rising seas and warming temperatures pose challenges for a critical, eco-friendly industry.

North Carolina is home to the eastern oyster (Crassostrea virginica), which can vary in size, shape, and taste depending on water quality and location. As the “Napa Valley of Oysters,” North Carolina’s pristine environment supports a variety of oyster “merroirs,” or flavors.

Oyster habitats range from deep water reefs in the sounds to shallow areas adjacent to salt marsh grasses. Although North Carolina’s wild oyster populations have declined to approximately 15-20% of historic harvest levels, various initiatives, including oyster farming and sanctuary systems, aim to restore wild populations.

Oyster reefs also provide habitat for a wide range of species, including fish, barnacles, crabs, anemones, and shrimp, improving biodiversity in estuarine habitats. This habitat additionally offers protection for many juvenile species, which in turn leads to increased dockside commercial seafood sales. Dockside sales and other retailers contribute $80.3 million to North Carolina’s $300 million annual wild-caught commercial fishing industry.

While Eastern oysters face many challenges due to our changing climate, they provide numerous eco-friendly benefits for coastal communities. For example, they filter algae from surrounding water, effectively removing impurities and improving water quality. Under certain conditions, in fact, a single oyster can filter 50 gallons of water per day. During this process, oysters also transfer nutrients from the top of the estuarine habitat to the bottom, creating an important link in the food chain.

Oyster reefs also help protect shorelines by acting as natural breakwaters that absorb wave energy and dissipate its power. “Living shorelines” — which incorporate native plants, oysters, and rocks instead of concrete seawalls — have become an increasingly popular tool to prevent erosion and damage from storm surges.

Although there are often consumer concerns about farm-raised food, oysters are unique in that they do not require any feed, while providing nutrients that include protein, calcium, iron, and zinc. As climate change continues to impact food supply and as demand for food increases, relatively low-maintenance protein sources like oysters will become increasingly important.

Delayed Harvests, Storm Damage, and Disease

Climate change has caused global shifts in many facets of the environment, including increases in sea temperatures, sea level, and storm intensity. Over the last three decades, sea surface temperatures consistently have reached record highs since reliable data collection began in 1880.

Over the last two decades, relative to coastal North Carolina’s sinking land, the Atlantic rose roughly 4.5 inches at Duck, 6 inches at Beaufort, and 8 inches at Wilmington. Droughts, flooding, and severe hurricanes have ravaged the coastlines of the United States. Warmer sea surface temperatures intensify tropical storm wind speeds, resulting in greater damage upon landfall.

Estuaries — where fresh rivers meet the salty ocean — are particularly vulnerable to climate change due to shifts in water level and temperatures in both upland and coastal areas. North Carolina has 2.2 million acres of estuarine environment along its coastline, and approximately 90% of North Carolina’s commercially significant species live in estuaries at some point in their life cycle, including oysters.

Rising ocean temperatures also adversely affect the physiology of Eastern oysters, leading to reduced rates of growth and reproduction. On the other hand, cooler waters provide more nutrients for oysters to filter feed, as well as higher oxygen levels, both of which support growth.

Oysters also rely on environmental cues from cooler waters, and particular salinity ranges, to initiate their reproductive cycle. Consequently, warming temperatures can result in delayed harvest seasons due to growth later in the season.

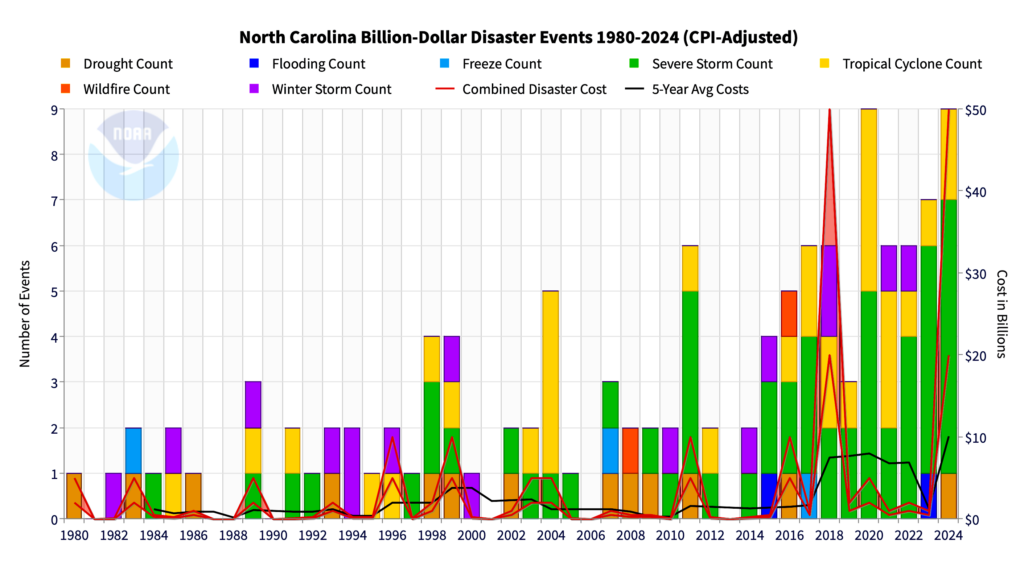

Warming ocean temperatures also contribute to intensified storms. Since 1980, there have been over 120 confirmed extreme weather events in North Carolina, including 54 severe storms and 31 tropical cyclones, each resulting in losses of over $1 billion to the state.

Direct impacts from storms include property damage, flooding, water contamination, and destruction of oysters or oyster gear, as well as extreme changes in salinity. Even years of increased rainfall can impact oyster farming, as the change in salinity from fresh waters can affect oyster survival, particularly in early life.

Hurricane Florence alone caused an estimated $10 million in damages to North Carolina’s shellfish aquaculture industry in 2018. Such storms also harm tourism and reduce public interest in traveling to the North Carolina coast, which indirectly affects oyster farming and other aquaculture businesses.

Oyster aquaculture is also facing significant challenges due to mass mortality events. The causes remain unclear, but warming temperatures facilitate the rapid growth and spread of bacteria and viruses. Additionally, environmental factors such as salinity, water quality and runoff — issues that storms and storm surge exacerbate — can further compromise oyster health.

Regardless of the specific causes, these mortality events have had devastating effects on oyster farmers in North Carolina. For example, in May 2022, several mortality incidents occurred along the North Carolina coastline, spanning 115 miles, with Stump Sound particularly hard-hit, resulting in oyster losses up to 90%.

NC State University’s Tal Ben-Horin is spearheading a new Sea Grant-funded study of mass mortality events, accounting for a wide range of factors in order to determine how growers can lessen or eliminate these events.

Supporting a Species and an Industry

Supporting oysters in North Carolina benefits coastal ecosystems and communities:

- Follow the North Carolina Oyster Trail to discover oyster farmers, restaurants, seafood markets, and educational experiences that promote and celebrate local oysters.

- Consider adopting an oyster through the North Carolina Coastal Federation, which also collaborates with The Nature Conservancy and the North Carolina Division of Marine Fisheries (DMF) to build oyster sanctuaries.

- Recycle oyster shells or encourage local oyster-selling businesses to do so, because recycled shells are vital for creating new oyster habitats.

More

A Booming Industry — And a New Threat

Allison Aplin is a masters candidate in environmental management in coastal and marine systems at the Duke Nicholas School of the Environment. She also serves as an outreach intern for North Carolina Sea Grant.

lead photo: Daniel Pullen.