“Comparatively, a bedrock well is the most cost-effective option.”

New research finds that drilling deeper groundwater wells may provide residents in counties along the Cape Fear River with safer drinking water. It’s a promising alternative for many people living near the river, where per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) — also known as “forever chemicals” — have seeped into shallow groundwater for years, contaminating private wells and threatening public health.

Many families living near the Chemours chemical plant in Bladen County, North Carolina, have lived with potential health risks for years because Chemours manufactures various types of PFAS, including GenX. These chemicals are used for non-stick cookware coatings, firefighting foam, stain-resistant clothes and carpets, and other products in the aerospace, automotive, construction, and electronics industries.

But new research from Tiffany J. VanDerwerker, a fellow for the North Carolina Water Resources Research Institute, and her NC State University colleagues Detlef R.U. Knappe and David P. Genereux reveals the deeper bedrock aquifer could hold the solution.

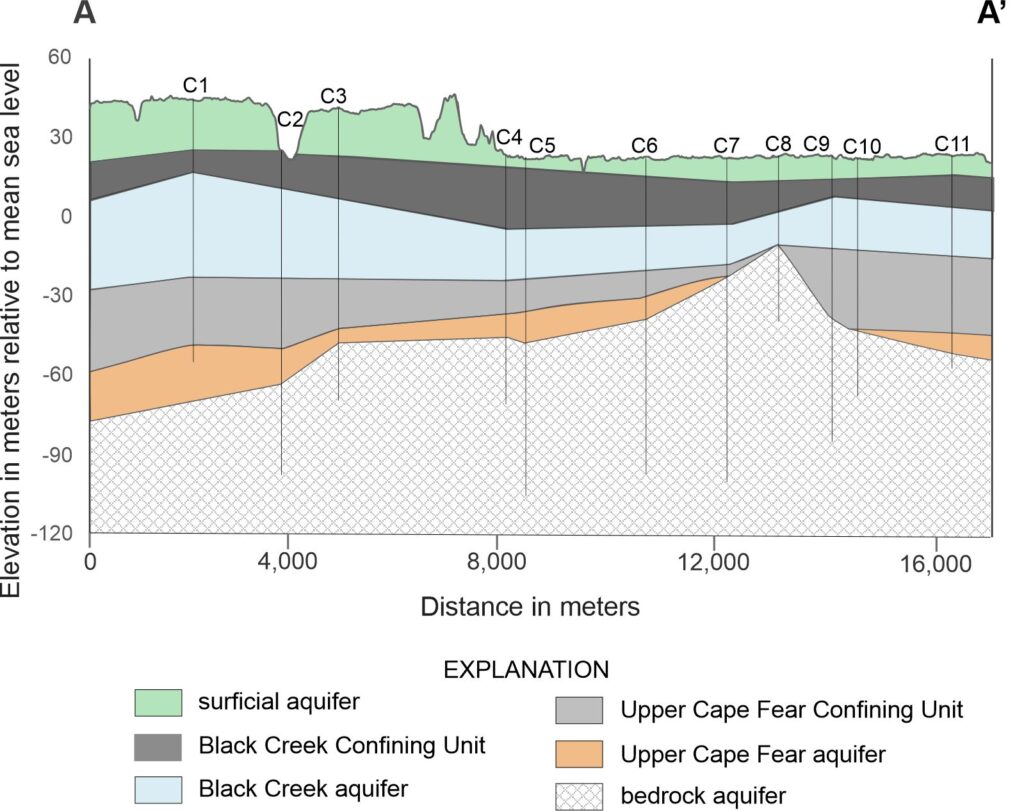

An aquifer is an underground layer of porous rock that holds water. The study area — covering parts of Cumberland, Robeson, and Bladen Counties in North Carolina’s southern Coastal Plain — includes four distinct aquifer layers: “surficial,” “Black Creek,” “Upper Cape Fear,” and “bedrock.”

According to the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), drinking water quality must meet established National Primary Drinking Water Regulations, which set maximum levels to limit chemical contaminants and impacts on human health. Although these regulations only apply to public water systems, VanDerwerker and her team used these regulations to guide their research. Encouragingly, the study found that many deeper wells, particularly those that reach bedrock aquifers, fall well within regulated levels.

“In terms of GenX, we see higher concentrations in the surficial aquifer,” says VanDerwerker, “and when we go deeper to the bedrock aquifer, all of the samples we evaluated were [within] the drinking water standards — which is good news in terms of PFAS contamination.”

The Cost of Deeper Drilling

To better understand aquifer use and groundwater quality in the area, the research team obtained and analyzed 222 well construction records from the Cumberland County and Bladen County health departments and North Carolina’s Department of Environmental Quality (NCDEQ). They also collected water quality samples from seven bedrock wells and two wells in the Upper Cape Fear aquifer.

Since the bedrock aquifer lies much deeper than typical private wells and requires more materials and time to construct, the team wanted to determine the cost for local homeowners.

“We talked to a driller who estimated that a bedrock well could cost over $30,000,” VanDerwerker explains. “Looking at the ‘Consent Order,’ a new bedrock well wouldn’t be covered for an individual residence.”

The Consent Order — established by NCDEQ, Cape Fear River Watch, and Chemours — mandates that Chemours reduce emissions and ensure residents have access to clean drinking water. For homes that qualify under the order, Chemours funds water filtration systems like Whole-House Granular Activated Carbon systems.

The study found that installation, maintenance, and quarterly testing of the filtration system could cost around $64,000 over 20 years. In areas with access to public water systems, Chemours would instead pay up to $75,000 for connection to public water supply and $75 monthly toward residents’ water bills, amounting to about $93,000 over two decades.

“Comparatively,” VanDerwerker says, the $30,000 “bedrock well is the most cost-effective option.”

However, she adds that NCDEQ only monitors the upper aquifers for over-pumping and overuse. “We can’t estimate the long-term sustainability of the bedrock aquifer,” she says.

Tradeoffs

Drilling to the bedrock aquifer, VanDerwerker says, is “not a silver bullet.”

“If you keep poking holes in the overlying aquifers there is the potential that the PFAS could flow downwards and contaminate the deeper aquifers,” she says. However, she adds, the risk of PFAS impacting deeper waters “can likely be partially managed through careful controls on well design and installation.”

Also, the research team found that the bedrock aquifer contains arsenic — a naturally occurring element in minerals primarily used in alloys of lead (for example, batteries and ammunition).

“Arsenic is a carcinogen — an agent that promotes the development of cancer,” she says. “So there are tradeoffs.”

Her study concludes that “arsenic treatment may be beneficial at some deep wells.”

As a longer-term solution, VanDerwerker advocates for investing in public water infrastructure. Ultimately, she says, the goal is to give families options, backed by science and guided by transparency.

“I hope that my research will be useful to homeowners making decisions about the choices that are best for them,” VanDerwerker says, “and to regulators as well.”

Read the full study:

Adapting to PFAS contamination of private drinking water wells near a PFAS production facility in the US Atlantic Coastal Plain of North Carolina

lead image credit: AdobeStock.

Emma Davies is an award-winning journalist and a contributing editor for Coastwatch. She is pursuing a masters of arts in liberal studies at North Carolina State University, with a concentration in communication and genetic engineering.

- Categories: