THE FATE OF A FISHERY: Shad and River Herring at the Turn of the 21st Century

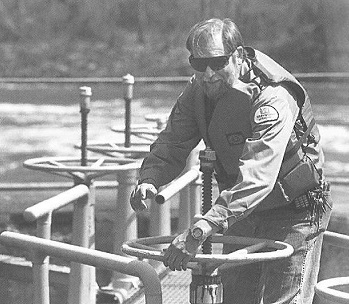

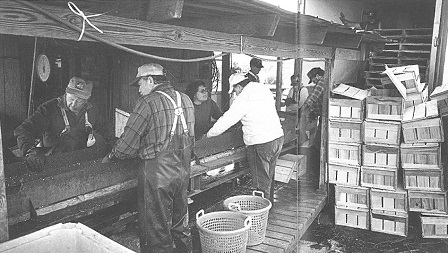

The sun has hardly risen over the Chowan River, but Herbert Byrum, his brother Bobby and crewman Hazel Rountree are already knee-deep in fish. River water, slime and silvery fish scales wash around their boats as they dip more wriggling bodies from the shrinking confines of the pound net — 40 pounds of fish per dip. When it’s full from gunwale to gunwale, their skiff holds about 4,000 pounds of river herring. The other fish — striped bass, perch, and catfish — to back over the side.

It’s beautiful fishing,” Herbert Byrum likes to say. So many glistening fish heaped together in the early morning sunshine certainly look like an embarrassment of riches. But each year, Bryum finds it harder and harder to fill his boat.

He has been fishing since 1964, when he was still in high school. River herring used to bring in three-quarters of his living. But as herring stocks have dwindled and N.C. Marine Fisheries Commission (MFC) regulations have become more and more stringent, his take-home pay from the fishery also has dried up. “Since 1994, it’s been cut down to just over 20 percent from the restrictions,” Byrum says. Where he used to catch up to $40,000 worth of herring a year, he now catches $10,000.

His father, grandfather and great-grandfather before him were commercial fishers. Like them, Byrum expects to keep fishing till he dies – but he doesn’t expect anyone to follow in his footsteps. “I’ve enjoyed being a commercial fisherman, but I wouldn’t want my kids to do it. They couldn’t survive. Crabbing basically keeps us alive now.”

A SHAD AND HERRING PRIMER

When North Carolina’s dogwoods bloom, the first shad and herring can’t be far behind, swimming up the 1ivers to spawn. First come the hickory shad in mid- to late-February, then the alewives in March. Bluebacks and American shad follow in three or four weeks. They are all anadromous fish that leave their salty ocean homes to seek spawning grounds in the shallow freshwater creeks where they hatched.

When the first explorers and settlers arrived, they found 1ivers teeming with fish. In 1612, William Strachey noted “Shadds great store of a Yard long” in Chesapeake Bay, and “great Shoells of Herrings.” In North Carolina, Algonquian Indians tended weirs across the streams. Settlers raided those weirs or built their own, and “kippered” the fish with smoke and salt much as their European forebears had done.

For generations, riverside communities celebrated this yearly provenance. The returning schools of shad and herring marked the end of each long, hungry winter and brought the promise of spring. Families scooped a year’s worth of fish suppers from the water with nets and baskets of all kinds. Most shad were eaten immediately, as they didn’t cure well with salt, but river herring could keep for a year or more if properly cut and brined.

In the 1760s, commercial fisheries were established on several of the state’s rivers, and pickled herring were shipped up the coast to Baltimore, New York and Boston; west to the Great Plains; and south to the West Indies.

Two Dutch brothers introduced the pound net in 1869, vastly improving the efficiency of the herring fishery overnight. By the turn of the century, shad and herring numbers already were dropping markedly. Technological innovations and industrial expansion were taking their toll in the form of overfishing, pollution and the destruction of spawning grounds.

Still, North Carolina’s fishing culture remained largely unchanged. Electricity and refrigeration were slow to spread to the remote eastern reaches of the state, and river herring remained one of the few meat sources poor families could afford. Until the mid-1900s, most households in eastern North Carolina would have a barrel of “corned” herring stashed somewhere in the kitchen.

Now the dependence on shad and herring is almost a memory. Though some bluebacks and alewives go to fishpacking plants for transformation into herring with cream sauce or other delicacies, most become fertilizer, fishmeal or bait. Shad are still a fairly valuable market fish, but their numbers have dropped so drastically that they are pursued mostly for sport.

Though commercial fishers are occasionally teased with an inexplicably good year, even the best years are nothing like the old days. The highest annual landings for river herring since 1887 came in 1969, with a haul of just under 20 million pounds. By 1990, the total landing was only 1.1 million pounds.

Since 1995, the MFC has regulated catches of both shad and river herring. Commercial ventures may take shad only from Jan. 1 through April 15, and there is a recreational creel limit of 10 fish per person per day. As regulators ponder a fishery management plan for river herring, temporary quotas slash the total allowable catch. The reduced quotas have forced some commercial fishing families out of business. Others, like Herbert Byrum, have diversified into fishing for crab, shrimp or catfish to make a living.

Last spring, I set out to find some vestige of the fishing culture that used to thrive along North Carolina’s eastern rivers. It’s mid-March as I leave Wilmington for a tour of three of the state’s great fishing rivers: the Cape Fear, the Neuse and the Roanoke. Jim Bahen, a North Carolina Sea Grant fishery specialist, is my intrepid guide. If I’m lucky, I’ll get glimpses of the fishery’s lucrative past, and perhaps, of hope for the future.

LOCK & DAM NO. 1, CAPE FEAR RIVER

The Cape Fear pours over the dam in a smooth brown curve, foaming white where it meets the lower water downstream. Bluffs rise on either side of the river. Along one bank, black rings in the grass mark the site of illicit midnight bonfires and fresh fish dinners.

On the river’s surface, a safe distance from the tumbling whitewater, men in bass boats and skiffs work the current with rod and reel or slow-moving drift nets. They’re pulling in fat, white American shad, which are bigger than their hickory shad cousins.

“The net fishermen are happy about the muddy water,” says Robin Hall, lockmaster at Lock & Dam No. 1. “Fish can’t see the net, and they swim right into it.”

Hall is popular with fishers, who call him from morning till night to find out how the river is running. He always knows. And thanks to him, many American and hickory shad are running the gauntlet of all those hooks and gill nets to find safe passage upriver through his lock.

Though boats have floated through the lock since 1915, fish present a greater problem. Shad can’t leap over the dam, which rises 11 feet above the water — and they don’t use the fish ladder. For years, Hall says, most fish pooled at the base of the dam, never reaching their upstream spawning grounds. “They’d swim in through the downstream gate, take one circle around the chamber, and go right out the gate again.”

While U.S. Secretary of the Interior Bruce Babbitt leads a nationwide campaign to blow up unnecessary dams, Hall has taken a less explosive approach. With funding from the Fishery Resource Grant program administered by North Carolina Sea Grant, Hall teamed with Mary Moser, a fish biologist formerly at the University of North Carolina at Wilmington, to study the movements of shad through the lock.

Radio signals from tagged fish confirmed his fears: Hardly any fish made it upstream during his usual locking procedures. But when he changed the arrangement of the gates and the flow of water inside the lock chamber, more fish stayed inside.

At the dam, we gather under a huge live oak tree to buckle on life preservers before venturing out onto the concrete beside the lock. The water curls far below us, the color of chocolate milk.

The new method for opening the gates creates a strong current flowing downstream along one side of the lock. Fish enter the lock and swim up the current until they hit the other end of the chamber. After circling back on the “quiet” side of the lock, they enter the current again and repeat the process instead of exiting on the downstream side. I watch the waves, hoping for a glimpse of a fish.

“There’s hardly a ripple if a shad comes up,” says Hall. “If there’s a splash, it’s more than likely a striped bass or blue catfish.” But I can’t see anything, even with Bahen’s polarized sunglasses.

Hall now performs three lockings a day during spawning season, just for the fish. In between, he leaves the gates open to attract more shad into the chamber. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, which operates the dam, has extended the same strategy to the two dams farther upstream. “Big schools of shad fry have been seen as far upriver as Fayetteville,” Hall says proudly. “With the three-hour lockages…80 percent more fish are being passed upstream.”

On that optimistic note, we head to the car. In the parking lot, families pack shad into buckets full of ice for the ride home. Some folks spare a few fish for their neighbors. Bahen says that many coastal plain residents still rely on shad for springtime dinners. “When the dogwoods bloom and the com is about two inches high, these people know it’s shad time,” he says.

GRIFTON, CONTENTNEA CREEK

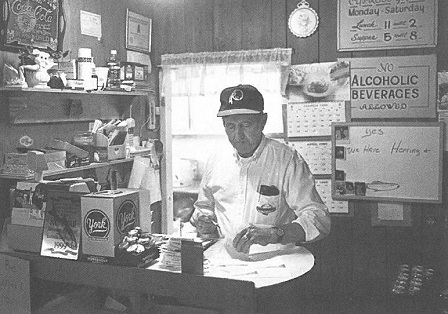

It’s already getting dark when we pull up outside the Grifton Country Store, a family business that caters to recreational fishers as well as road-weary drivers in need of a soda and snack. When we walk through the front door, I hear crickets chirping. A sink holds cardboard boxes full of bugs for bait, alongside the minnows and worms. One wall is ornamented with lures in plastic bags: shad darts, spoons, and flies.

Our host Lubie McLawhorn, who owns the store with his wife Nettie, leads us into a back room. The smell of hot oil fills the small space, and on a counter, a line of pans holds floured fillets of trout, hickory shad, river herring, American shad and two kinds of roe. Master cook Allen Shirley is conducting a fish fry just for us. The secret, he says, is to add vinegar to the oil just before adding the fish. “It crystallizes the bones.”

When the fish are hot, we fill plates with fillets, fried hunks of roe, potato salad and coleslaw. I’ve never eaten roe before, and roll the tiny firm grains across my tongue. Despite the vinegar, the herring and shad are crunchy with needle-sharp bones.

The locals eat the fish — bones and all — wrapped in white bread with ketchup. “If the bones catch in your throat, you swallow the bread and it catches in the bread and passes on through,” McLawhorn tells me.

Stories around the smoky table focus on the good fishing. “The hottest spot is at the mouth of Contentnea Creek,” McLawhorn says. “There’s more (shad) in supply this year than any year I can remember. I’ve never seen a run like this before.” This very day, in fact, a Greenville man brought in his catch to be weighed — a 3.8-pound hickory shad that tied the state record established in 1992. I can’t help but think of Strachey’s yard-long shad, missing from these waters for centuries.

Anticipation is building for the Grifton Shad Festival, which started in 1971 to celebrate the town’s long love affair with hickory shad. A sport fishery for shad has flourished on the Neuse River and Contentnea Creek since the 1800s, and the hook-and-line fishery continues to grow. While American shad and striped bass or rockfish were high-dollar, export fare for much of the 20th century, herring and hickory shad fed the locals.

Janet Hasely, a New York native, helped establish the festival to recognize the town’s fishing heritage, and she continues to be its biggest promoter. She drops by after dinner to share some of the special “Mo Shad” merchandise, ranging from flags and T-shirts to jewelry. “Mo Shad,” the Grifton mascot, is a bony hickory shad skeleton that appeared with the words “Eat Mo’ Shad” on the town’s old drawbridge.

The festival features prizes for the biggest and earliest shad catches of the season, a fish fry, a “shad toss” in which participants compete to see who can hurl a dead fish the farthest, and a casting contest with rod and reel. Arts and crafts booths, a “Shad Queen” contest, parade and street performances round out the festivities.

The annual event routinely draws about 10,000 out-of-town visitors, and McLawhorn appreciates the influx of sport fishers. Amid rumors of the good shad run, business has been especially brisk. “I’ve ordered more fishing tackle in the last month than I usually sell in the whole spring.”

The next morning, I try out some of that tackle. I spend a good 20 minutes figuring out how to cast into the current at the mouth of Contentnea Creek, as McLawhorn and Bahen duck and grimace behind me. Finally, after at least half an hour of ineffective casting — during which Bahen reels in three fish and McLawhorn, two — I get my first nibble. My line pulls hard to the right — my first fish ever.

If anything, the men are more excited than I am. Sadly, my first hickory shad disappears into the muddy water as I bring it alongside the boat. Bahen declares it a catch and release.

Even more determined, I flick the line out into the stream over and over. Around 11 a.m., as my casting wrist is getting numb, I pull a two-pound hickory roe shad over the side of the boat. Smiling proudly, I hold it all wrong for the camera.

There’s a long road ahead with no refrigeration, but I wish I could pack up my fish and take it home to eat. I’m a child of grocery stores and fast food chains, and the only herring I’d eaten before yesterday came in a can with a peel-back lid. Self-sufficiency is a flavor I’ve never tasted. McLawhorn assures me that someone will enjoy my catch and adds my shad to the others in the fish well. Then he guns the engines for a fast, cold ride back to the boat ramp.

JAMESVILLE, ROANOKE RIVER

As we drive north, I scan the roadside canals for signs of fishing. In the old days, kids used to suspend bushel baskets from the bridges, waiting for telltale vibrations to travel up the ropes to their hands. A deft flick of the wrist, and up came the dripping basket with a few herring in it. Men and women would fish in the shallows with bow nets made from curved pieces of juniper and hand-knotted twine. When fish flooded the streams, a good bow net could trap more than 100 herring in a single dip.

In Jamesville, once home to three commercial fisheries, seine hauls were so heavy that horses had to pull them in. These are the kind of memories Jeff Phelps wants to preserve in a Jamesville museum. An outspoken member of the town board, he appreciates the proud local traditions of the river herring fishery. “Elders have told me that for hundreds of years, when the herring would come up the river, there was some kind of festival here…. They’d have a seine all the way across the river and they’d crank them in. People would come down to the river in their Sunday dress to buy herring.”

The herring run and the festival historically coincided with Easter Sunday and homecoming for local churches. The modem Jamesville Herring Festival is held on Easter Monday every year. For Phelps, a museum is the next logical step to recognize Jamesville’s heritage. History buffs also could pull tourist dollars into an economically depressed county.

He hopes to open a temporary museum in the town hall, displaying old photographs of the fishery. If his dreams become reality, a permanent museum will be housed in the Burras House someday. “It’s the oldest building in town, established around 1790,” Phelps says. “All the rest of the buildings were burned in the Civil War.” The museum could include Civil War-era artifacts and relics of the fishery. Phelps would also like to see Jamesville get a public boat ramp — something inexplicably missing from a town so defined by its relationship with the river.

Jamesville is so renowned for its herring that it boasts the Cypress Grill, a weather-beaten restaurant open only between January and May. What’s on the menu? Herring, herring and herring. People drive from all over the state to eat there, and at the neighboring River’s Edge Restaurant. But when we arrive in town and drive to the parking lot overlooking the water, we find both restaurants closed and few people on the water.

McLawhorn had warned us that herring had been scarce in the Roanoke River. “The dams should be opened…they’re holding the fish back. They need to turn loose the water.” Upstream from Jamesville, at Lake Gaston, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers operates dams that control the water levels in the river system, and the 1999 springtime drought has meant low flow for months. Salt water has pushed far inland, and fishers worry that herring aren’t getting the signals they need to push upriver to spawn.

“What are you catching?” I ask veteran fishers on the riverbank. They’re selling a handful of river herring from a waxed cardboard box in the back of a pickup truck.

“Mostly rock,” they tell me. Striped bass have made an amazing comeback from dangerously low levels a decade ago, and their catch is still highly regulated.

One of the fishers, Billy Williams, argues that similar state regulations are killing the commercial herring fishery. “They’ve cut us down to 100,000 pounds of fish for the Roanoke and Albemarle,” he says. “We’ll never catch any more fish.”

Vance Price nods. “Three or four years ago, you caught 1,200 fish in one drift,” he says. This year, the fishers’ nets come up almost empty.

TAKING STOCK

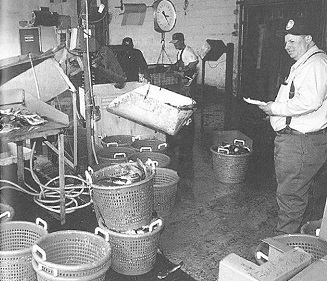

Herbert Byrum’s back yard slopes right down to a branch of the Chowan River. Between his place and his brother’s is a fish house where they unload their catch onto conveyor belts and into the backs of trucks bound for Perry-Wynns or Murray-Nixon Fish Company. “We got through Floyd pretty good,” Byrum says, long after the 1999 spring run is over. “It tore up our piers and our unloading conveyor…There was probably two and a half to three feet of water in the fish house.”

Far more devastating was 1999’s low catch of herring. “We did a little sorrier up here than we generally do,” Byrum says. “The rock are taking ’em. They stayed in the south end of the river.” He estimates that he caught 5,000 to 10,000 pounds of herring a day and up to 6,000 pounds of striped bass, though he could only keep 10 of the rockfish per day due to MFC regulations.

It’s a far cry from the 1930s, when farmers in the area would come to the river to buy a year’s worth of herring for their tenants. In more recent times, Byrum has faced several adversaries in the fight to keep the river herring fishery alive. Ditching and draining of the river’s tributaries for agriculture destroyed some herring spawning grounds. In the 1970s and 1980s, pollution from upstream industries and runoff from agriculture turned the Chowan River into a green soup of algae and dead fish.

Massive cleanup efforts that began in the 1980s have resulted in improved striped bass and white perch fisheries and decreased incidences of algal blooms. But now that the water quality is back, years of over-fishing are taking their toll. The state has enacted strict rules to protect river herring stocks and let their numbers rebound, but to many struggling commercial fishers, the regulations curbing their industry are anathema.

Fishers who work the inland waters must comply with regulations set by the N.C. Wildlife Resources Commission, while coastal waters are regulated by the Marine Fisheries Commission.

Sara Winslow, fish biologist with the N.C. Division of Marine Fisheries (DMF), explains the rationale behind the 1999 regulations, which reduced the quota for the river herring fishery to 450,000 pounds. The quota was subdivided to include 300,000 pounds from the Chowan pound-net fishery; 100,000 pounds from the Albemarle gill-net fishery, which includes the Roanoke River; and 50,000 pounds that could be assigned at the DMF director’s discretion.

“River herring stocks are still overfished and populations are at extremely low levels,” Winslow says. “The number of spawners in the population is very low.” Stock assessment analyses also show that the number of recruits — fish that reach sexual maturity and return — is also very low.

Each year, the DMF samples the river herring harvest to assess the overall stock. Most of the herring harvested are 3 to 5 years old — usually first-time spawners — suggesting that the older ones have been fished out. Younger fish are still in the ocean, maturing before they spawn for the first time. “We want to see a wide span of age classes represented in a harvest,” Winslow says. “For the last 10 years, the majority of the harvest is from one- to three-year classes.” In the 1970s, up to eight-year classes were represented.

In February, the Marine Fisheries Commission adopted a Fishery Management Plan for river herring. The plan limits the commercial herring fishery to 300,000 pounds per year. That total allowable catch is divided into three portions: 200,000 pounds for the poundnet fishery on the Chowan; 67,000 pounds for gill nets in the Albemarle Sound herring management area; and 33,000 pounds that the DMF director can assign. With the new limits, the division expects it will take 14 to 24 years for the river herring fishery to recover.

The commission also instituted a new cap or daily creel limit of 25 river herring for recreational anglers.

The final herring management plan vote came after criticism of an earlier proposal that would have limited river herring to a 100,000-pound bycatch fishery. Under that plan, herring would only be harvested incidentally, as a limited “bycatch” when fishing for other species.

Byrum was among a group of fishers who thought the bycatch proposal would result in wasted fish. “If it’s a 25 percent bycatch, you’ll have to catch 100 pounds of white perch and catfish before you can take in 25 pounds of herring.” Since a pound net holds 5,000 pounds of fish, if the rest of the fish are herring, they’ll have to be thrown back. And herring just aren’t the same after being squeezed in a tight net with a lot of other fish. “That’s 4,875 pounds of herring that will die and get thrown away,” Byrum says. “That’s stupid. Herring is a fragile fish. If you bunch it up, it’ll die.”

The 300,000-pound limit was approved after the Marine Fisheries Commission again heard from the co-chairs of an advisory panel for the river herring management plan. The panel had recommended a total catch of 450,000 pounds. Jerry Schill, president of the North Carolina Fisheries Association, says he was pleased that advisors had a chance to present their proposal again.

There may be no simple solutions for the recovery of these fisheries. Shad and river herring are more than fine-tasting, silvery fish that swim up North Carolina’s rivers every spring, pulled by forces we neither see nor feel. For generations of hard-working citizens — often the state’s poorest and most invisible people — they have been gifts from the river, a seemingly endless bounty that created jobs, traditions, and plenty in the midst of want.

If the numbers of shad and herring continue to dwindle, a part of North Carolina heritage vanishes with them: three centuries of town reunions on the riverbank, baked shad at Easter, fresh herring at the Cypress Grill, 5,000 pounds of fragile fish flashing in a net.

As Byrum says, it’s beautiful fishing.

EDITOR’S NOTE:

Much of the historical information for this story is drawn from the master’s thesis of Charles L. Heath Jr., “A Cultural History of River Herring and Shad Fisheries in Eastern North Carolina: The Prehistoric Period through the Twentieth Century,” prepared in 1997 for the East Carolina University anthropology department.

This article was published in the Spring 2000 issue of Coastwatch.

For contact information and reprint requests, visit ncseagrant.ncsu.edu/coastwatch/contact/.