THE GREAT DIVIDERS: OLD-FASHIONED DRAWBRIDGES DWINDLING ALONG COAST

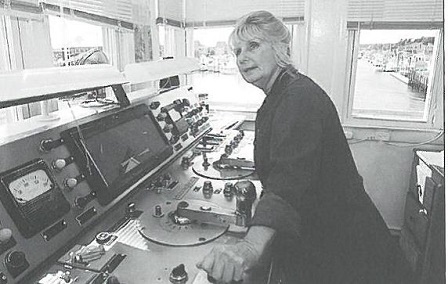

Perched in a tiny wood building high on the edge of the Wrightsville Beach bridge, Nancy Cayton focuses her binoculars south toward the Intracoastal Waterway.

As she spots a large sailboat, she’s interrupted by a radio call. The captain asks her to delay the opening until he arrives.

“If you can be within the half-mile marker, I can hold,” responds Cayton, a bridge tender at the Wrightsville bridge.

After seeing that the sailboat is going to make the marker in time, Cayton lets the other captain know that he will have a four-minute delay.

As the two large sailboats near the bridge, she bends over a console that controls electronic devices, stretching her elbows up like a flying bird.

After pushing several buttons, a siren horn sounds. Gates drop down to stop traffic to and from the beach. Then the bridge splits in two pieces. Within a few seconds, Cayton waves as a 25-foot sailboat from the Isle of Palms, S.C., motors through the bridge opening. The boat continues on the dark green water of the picturesque Intracoastal Waterway past pastel-colored buildings and marinas.

“I talk to people all over the United States,” she says. “It is an interesting job.” Every hour, Cayton opens the creaky green bridge for recreational boat traffic.

As the bridge splits, the gears grind. The traffic halts on both sides of the 90-foot horizontal span. “If a malfunction occurs, I have to go to the old way and open the bridge manually,” she says.

About four minutes later, Cayton stands at the console and closes the bridge. A siren goes off five times. The bridge sections fit back together. The gates open, and traffic roars by. Access to and from the island is restored.

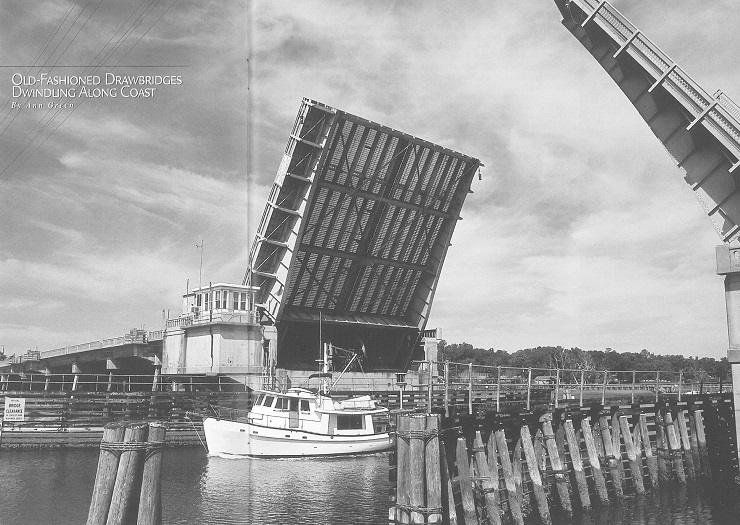

The Wrightsville Bridge, which straddles the Intracoastal Waterway, is one of only 12 coastal drawbridges still maintained on North Carolina’s coast by the N.C. Department of Transportation.

Built in 1957, the steel and asphalt drawbridge also opens any time a commercial boat comes through.

“There’s not much commercial traffic here,” says Cayton, who is dressed in jeans, a jean jacket and tennis shoes. “We get only a few tugs and trawlers this time of year.”

As a bridge operator for over 20 years, Cayton has seen her share of recreational and commercial boats.

SEASONAL MIGRATION

The busiest seasons are the fall and spring when large yachts and sailboats owned by “snowbirds” crowd the waterways as they migrate to and from Florida, the Bahamas and other southern points.

“We can have anywhere from one to 24 boats,” says Cayton while watching boat traffic from a building on the bridge’s edge during a busy fall day. “Today we had 12 boats come through at one opening.”

As the population in Wilmington has exploded, the number of cars and trucks rattling across the bridge has increased.

“There is a lot more traffic than there was 20 years ago,” she says. “It has doubled or tripled.”

The large amount of vehicular traffic — more than 400 cars waiting during one opening — has created wear and tear on the span. Because of a cracked brass bearing on the western half of the 44-year-old span, the Wrightsville bridge was closed for vehicular traffic, but not pedestrian traffic, on several nights in February.

Before closing the bridge, bridge tenders give aging bridge parts regular boosts of lubricating grease. On a recent day, a bridge operator in a white suit stood beneath the bridge on a ladder and greased the bridge’s gears. Earlier, Cayton had lubricated the gate and the trunion — the balance that keeps the bridge open.

“We each have a section to grease,” says Cayton, whose duties include wa5hing the building’s windows and blinds.

REPLACEMENTS CONSIDERED

Although no drawbridges are scheduled to be replaced at this time, DOT is conducting preliminary feasibility studies on the Sunset Beach and Beaufort bridges to assess whether the bridges need to be replaced with high-rise structures, says Lin Wiggins, director of DOT’s Bridge Division.

The Beaufort Board of Commissioners supports a DOT bridge improvement plan for a new thoroughfare and bridge for U.S. 70 East, according to a recent resolution.

In addition, the town board wants to keep the Grayden Paul drawbridge or a mid-rise fixed span at the present location so local traffic will have access to downtown Beaufort, according to Corinne Geer, interim town manager. “We are also working with the Coast Guard for amended scheduled openings every 30 minutes,” she adds.

However, DOT doesn’t see any advantage in just building the thoroughfare and not replacing the structure, says Wiggins.

“We routinely get complaints from both sides on the opening schedule for the drawbridge,” he adds. “There is also the continued maintenance and operation cost. Eventually, the bridge will have to be replaced. Nothing lasts forever, especially a large structure with moving parts.”

For the past 20 years, the Sunset Beach Association has opposed proposals for a high-rise bridge at Sunset Beach. The bridge is the only link between mainland Brunswick County and Sunset Beach, the state’s westernmost and southernmost barrier island.

However, DOT supports building a new bridge.

“DOT’s recommendation for a high-rise replacement for Sunset Beach is based on future operating costs of movable span structures and the conveyance of both vehicular and maritime traffic,” says Wiggins. “It is a very difficult operation to balance openings for vehicular traffic needs and maritime needs as well.”

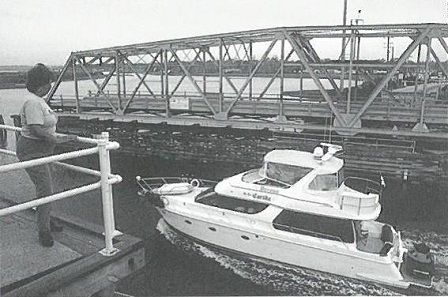

Built in 1959, the Sunset Bridge is the only floating pontoon bridge in North Carolina. A view from the one-lane bridge offers a wonderful visual contrast — a seagull fluttering over a sea of marsh grass on one side and a man fishing on wood pilings near a trailer park on the other.

On a recent day, bridge tender Tom Hewett walks down steep spiral steps to open the bridge, which rests on a barge. As a he pulls a cable, the bridge separates from the roadway and makes a 90-degree turn as it meets the pilings in front of the roadway.

As each boat goes through, Hewett jots down the boat’s name, direction and time of entry so he can have a record for the Coast Guard.

“The Coast Guard needs records for missing and stolen boats,” says Hewett After the last boat — a sailboat from Canada — clears the opening, Hewett adjusts the cable. The bridge swings back around and fits into the roadway like a puzzle piece.

“It usually takes 10 to 15 minutes for an opening,” says Hewett, who saw a busy fall.

“I have seen some of the biggest pleasure boats ever going through,” says Hewett. “I have seen boats that cost from $8 to $10 million.”

OPEN 24 HOURS

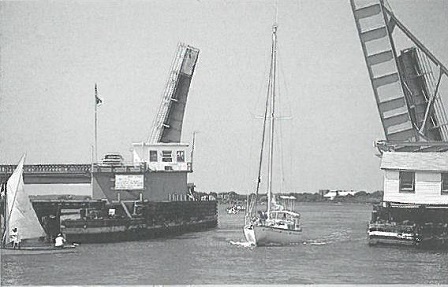

Pontoon and swing bridges on North Carolina’s coast operate round-the-clock. As Diane Edens surveys the boat traffic around the Surf City bridge near Topsail Island, it’s pitch dark. Only a few boats twinkle on the churning waters of the lntracoastal Waterway.

“One good thing about the job is that you see the sun come up here,” says Edens, who has been at work since midnight. “You also see the full moon shine on the waterway.”

On this morning, the sky blazes a bright red. Again, there is also a distinct visual contrast between the two sides of the bridge — a trailer park and a muddy brown marsh on one side and piers and houses on the other side.

Edens, who has been tending the historic Sears Landing Bridge since 1978, was the first female bridge tender in North Carolina.

“It was a challenge the first time,” she says. “Nobody worked here but men.”

Now many of the bridge tenders are women. It’s a job that is quite hectic.

Edens sits in front of a console in a tiny wood-paneled room decorated with a television and photo of her white Pekinese. She watches the boats and then answers a call from the National Weather Service in Wilmington.

“They want to know what the direction of the wind is,” says Edens. “We have a wind gauge instrument.”

Edens also monitors the radio for information from the rescue squad, Coast Guard and boats.

“You have to be alert and listen to all the radios,” she says. “Sometimes, we get a call from the rescue squad. We close as soon as we can.”

The swing bridges also shut down during hurricanes.

“If l am working, I am usually the last to leave the island,” says Edens. “I have to take down the gates and put chains at each end of the bridge to keep it from moving. I also have to lock up and turn the electricity off.”

On rare occasions, the bridge is shut down for a boat accident.

Several years ago, a barge hit the fender system — wood pilings that protect the bridge substructure.

“The dredging outfit came through this building and threw me on the other side of the room,” says Edens. “It yanked every connector off and pulled the cable through the concrete. I wasn’t hurt, but it was not a good feeling.”

Bridge tending is often a solitary job. The only time the operators communicate with other people is when they radio a boat captain or another bridge tender relieves them.

A few minutes before Eden’s graveyard shift is over, Faye Phelps comes in.

Phelps has tended the Surf City bridge for 10 years.

“It is a good job,” says Phelps. “You are more or less your own boss. Nobody bothers you.” Most of the time, she says the bridge openings and closings run smoothly.

“Ninety-eight percent of the boat captains are good,” she says. “But, every once in a while you do get someone that is hard to get along with. Some won’t answer the radio. That makes it tough to help them through.”

As Phelps scans the waterway with her binoculars, it is clear of boats. But she’s enjoying the view.

“You can always enjoy the pretty sights,” she says. “One time, we even had a drawbridge from Edenton come through on a barge. The owner of Barefoot Landing near Myrtle Beach couldn’t get a bridge built so he bought his own.”

BRIDGING THE DISTANCE

Along North Carolina’s coast, there are a variety of drawbridges — from the two-lane bridge that connects Straits to Harker’s Island to the towering Memorial Bridge over the Cape Fear River in Wilmington. Here are some other bridge tidbits from the N.C. Department of Transportation:

- The oldest operating drawbridge, which was built in 1931, is on U.S. 158 over the Pasquotank River in Elizabeth City.

- The newest bridge is a dual structure that was built in 1972 over the Pasquotank River.

- The busiest drawbridge for boat traffic is over the Alligator River in Tyrrell County. In 1999, 5,406 vessels went through the bridge opening.

- The state’s tallest drawbridge is Wilmington’s Memorial Bridge with a clearance of 65 feet.

- The shortest drawbridge is on U.S. 17B over the Dismal Swamp in Camden County.

For more information about North Carolina drawbridges, visit: https://www.ncdot.gov/travel-maps/maps/Pages/drawbridges.aspx.

This article was published in the Spring 2001 issue of Coastwatch.

For contact information and reprint requests, visit ncseagrant.ncsu.edu/coastwatch/contact/.

- Categories: