The riches of the North Carolina coast — sparkling beaches, winding shores and hidden coves, vibrant port cities, and abundant fishing — include another kind of treasure, often the buried kind.

Hundreds of historic shipwrecks lie underwater, typically within a few hundred feet of shore. Occasionally they rise up from their watery resting places to emerge just beyond the waves or even wash onto the beach. Others, including Queen Anne’s Revenge, Blackbeard’s flagship, rest on the sea floor, attracting recreational and scientific divers who are curious about these vessels’ history and cargo.

Along with romance and mystery, these shipwrecks carry priceless caches of artifacts and information, making them valuable sites for scientific research and archaeology.

Since 2007, North Carolina Sea Grant has supported promising research at East Carolina University through its Maritime Heritage Fellows program for graduate students. In 2012, the program funded two projects that will significantly advance underwater archaeology and conservation.

Daniel Brown is looking for clues about the identity of an ancient wooden shipwreck that floated to shore near Corolla about three years ago. The oldest found in North Carolina, it also may be the oldest on the East Coast.

Thomas Horn is studying the 1877 wreck of the USS Huron just off the coast of Nags Head. His study will evaluate how seasonal variables, such as temperature changes, affect corrosion on an iron vessel.

These projects, undertaken as part of their master’s degree studies, will answer some long-standing questions about the effects of salt water, ocean currents and the passage of time on ships of all kinds, while uncovering missing pieces of the state’s own story.

“There is an entirely unwritten history of North Carolina that we’re trying to discover,” says Bradley Rodgers, director of ECU’s maritime studies program, who serves as Brown’s adviser. “These are nonrenewable resources. If they are destroyed, either by man or by nature, we lose a big chunk of our past. They are time capsules of the period for which they existed. If they disappear, we lose our knowledge of that period.”

Nathan Richards, ECU faculty member and head of the maritime heritage program at the University of North Carolina Coastal Studies Institute, advises Horn on his study of the Huron. Richards cites the significance of these wrecks — and the research on them — for their contributions to maritime history and archaeology.

“A lot of people care about the Huron,” he says. “The best way to manage a ship like this one is to be armed with data. If we can tell if the Huron is stable or corroding, then activities can be determined to potentially save it, so it can be preserved and enjoyed by future generations.” What’s more, Richards add, the research will contribute to worldwide understanding of saltwater corrosion.

Shipwrecks attract more than historians and archaeologists. Divers and tourists from around the world come to the state’s shores and coastal museums to learn more about colonial times, pirates, smugglers, Confederate blockade-runners and even the German U-boats that stalked the U.S. Navy near the Outer Banks during World War II.

Littered with shoals, shallow waters and irregular borders, the coast earned its nickname as the Graveyard of the Atlantic. Indeed, thousands of wrecks may lie off the state’s coast. Most remain buried in the seabed, somewhat protected from destruction, but exposed to decay from salt water, sea life and hurricanes. Knowing the best ways to preserve them under water or above ground will protect these assets for researchers, tourists and historians alike.

MYSTERY WRECK

For two years, residents of Corolla, a small village in the northern Outer Banks, watched a battered wooden hull floating just beyond the shore. It bobbed on the waves and occasionally landed onto the beach before washing away again. A strong nor’easter in late 2009 dislodged it from the sand and in the subfreezing temperatures, the ship began to break apart.

If it shattered, it would be lost forever. Thus, a group of interested volunteers were joined by staff from the state Underwater Archaeology Branch, part of the N.C. Department of Cultural Resources, to haul the remains inland to safety.

It remained for a time on the grounds of the Currituck Beach Lighthouse, where visitors, researchers and archaeologists had a chance to get close to one of the oldest shipwrecks on the East Coast. Little is known about the ship, which is believed to date from the early 17th century, possibly as early as 1609.

Many ECU maritime studies students worked on the ship in 2010, measuring it, drawing its features and examining it for identifying clues. But for Brown, it was more than a summer job — it became his master’s project. He’s since spent countless hours searching for information about its origin, construction and precise age. While no one knows its name, the ship bears a stunning resemblance to a famous vessel from Bermuda, Sea Venture, that was the subject of Shakespeare’s The Tempest.

“It’s been very much of a detective story,” says Brown, who is one of the Sea Grant fellows. “I’m trying to find evidence about it, facts, where it came from, what it was doing. Was it a warship? Merchant vessel? Privateer? There’s no bumper sticker. There’s no license plate.” The ship is believed to predate the Queen Anne’s Revenge by about a century.

Facts about the mystery wreck don’t come easily. Even determining the wood type and construction methods has taken months of scouring and translating records to learn about types of European timber used in shipbuilding.

“Waterlogged wood is very delicate,” he says. Once wood dries out, the DNA disappears with the other living material, leaving only a hollow cell wall. Without any contents to support it, the cell wall collapses, accounting for the shrinking and eventual decay of wooden ships once they’re on dry ground.

So far, Brown feels comfortable identifying the wooden hull as white oak. A very common European species, Quercus sessiliflora grows across the continent as far south as the Spanish Mediterranean and into England. Yet even pining down the type of wood may not give up much information about the ship’s provenance, as timber was traded from the Baltics to the Mediterranean and beyond to locations in the Netherlands, England and Spain.

It’s like the ship, a large galleon estimated at 70 to 90 feet long, could have carried as much as 300 tons and was engaged in the lucrative colonial triangular trade between England and Europe, the Caribbean, and the New World. It was probably hauling or retrieving tobacco, wood or even settlers, who may or may not have made it to shore.

WINDOW TO THE PAST

In addition to searching for clues about its origins and identity, Brown believes his work will lead to better conservation methods for wooden ships. Once dry, a dramatic and rapid deterioration begins. “There are too many shipwrecks to save them all,” he says. “It’s a good policy to leave them in place.” Indeed, he notes, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, or NESCO, standard is to preserve wrecks in situ.

Once this wreck washed ashore, however, it became critical to save it before more damage occurred, providing researchers like Brown a golden opportunity. He has spent time and is now considered a contributing researcher, on Vasa, the famous Swedish ship that sank in the Stockholm harbor in 1628 and now has its own museum. That ship has been kept in a constant stream of preservatives and carefully controlled humidity for years to slow its decay.

Like Vasa, Corolla’s mystery ship “is a window to the past,” Brown says. In addition to focusing on the ship’s construction and materials, including the oakum — old rope pounded into cracks and used as caulking — he’s studying the artifacts found stuck to it.

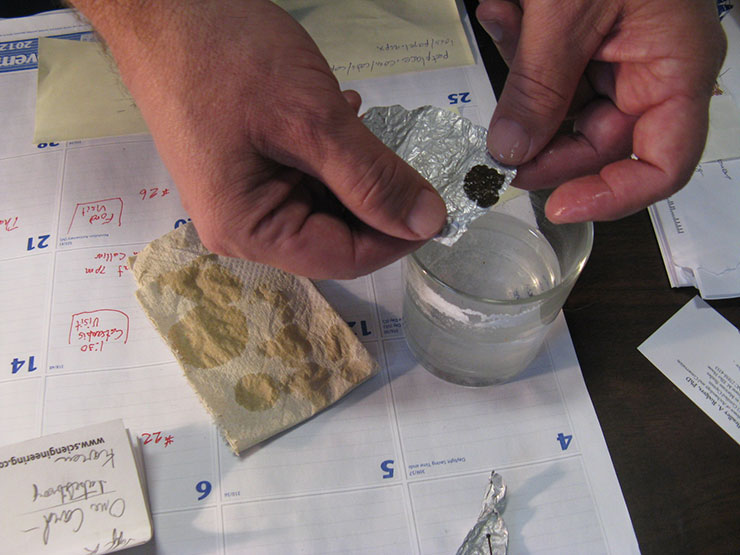

They include coins dating from the time of Louis XIII who reigned in France from 1610 to 1642. These coins, with embossed fleur-de-lis imprints, help date the vessel. In addition, a brass pin found on the wreck is undergoing conservation. These pins are so ubiquitous, however, that their diagnostic value is limited.

Brown has compared the unnamed wreck to 20 other wrecks so far, and feels confident that it is not Spanish or Portuguese because its construction uses more wood fasteners, known as treenails — pronounced “trunnels” — than iron ones. The wreck yielded hundreds of treenails, and only nine iron bolts.

He believes it probably sank in deep water, and made its way over the centuries to shore. That so much of its remains intact — it’s about 17 by 30 feet today — serves as a testament to the sturdiness of its construction.

Before it washed up, the keel was visibly attached to it. Although it broke away by the time the wreck reached the shore, the keel was still useful in identifying the type of ship.

His next research steps include possibly having a timber lab examine the wood at a microscopic level for clues about its identity and origins. To do so, though, would mean removing a sizeable piece, several inches wide. He wonders if it’s worth it to cause so much damage.

“I took the topic on because I was interested in ship construction,” he says. “I did not know what I was getting into — how much of an enigma this ship would be. I’ve had to be creative in my research techniques to get evidence.”

Brown has about 1,700 photos, which he has crossed referenced to date its recent history. “You can see the wreck over two years move around and break up, a piece here, a piece here, until in 2010 you get that big break up,” he says.

“Everybody thinks Pilgrims came to America and it was a happy story,” he continues.

But he notes that there were many unsuccessful attempts before the English were able to achieve their first settlement in Virginia. This nameless ship might be part of that narrative.

“North Carolina was a stepping-stone to establishing Jamestown. It plays a bigger role in history than most people realize,” Brown explains.

VITAL SIGNS

The iron steamship USS Huron left port at Hampton Roads, Va., on Nov. 23, 1877, for a scientific trip to Cuba. However, it wrecked near Nags Head, taking 98 men to their death in the frigid water.

This notorious episode made it “the Hindenburg of its time,” Horn says, and led to more federal funding for lifesaving stations. Built in 1875, the ship represents a transitional period in shipbuilding, an original hybrid iron steamship with supplemental sails. Steel ships would soon become standard. The USS Huron is the state’s first designated shipwreck preserve, and the site of much diving and exploration.

One of the oddest forms of ship deterioration happens when metal, especially iron, is submerged for long periods of time in sea water. Salt water creates a highly corrosive setting and the metal oxidizes or rusts, just as it does on dry ground.

Meanwhile, tiny life forms such as coralline algae attach to shipwrecks, while other sea creatures take advantage of the presence of minerals or organic materials that were used in construction or found on board.

Movements of sea water, combined with the salt-ion exchange and natural secretions of sea life, create a dynamic underwater setting that develops a life of its own.

Concretion, which is a plaster-like casing, forms around the metals, affixing items to each other like glue. It protects some with a cement-type casing by hiding them beneath layers, often several inches thick.

Some maritime archaeologists believe leaving wrecks in place may be the best way to preserve them. Their research must determine first the conditions that lead to the worst forms of corrosion. Along with location, storm frequency and currents, water temperature may be an important variable.

That theory led to Horn’s study. Originally from Los Angeles, Horn graduated from the University of Hawaii with a degree in anthropology. While he’s been diving most of is life, a trip to Easter Island in 2007 sealed his interest in archaeology. His Sea Grant-funded study, Determining Seasonal Rates of Corrosion in Ferrous-Hulled Shipwrecks: A Case Study of the USS Huron, will examine the rate of corrosion and concretion build up on this iron ship.

“Corrosion monitoring is interesting — and a challenge,” he says. “I enjoy the electrochemistry of it.”

Horn is investigating whether changes in temperature, salinity and dissolved oxygen content affect corrosion rates. His results will help determine how best to manage the site in situ, such as by installing sacrificial metals that will corrode instead of the ship, to protect critical areas. Once completed, his study will help map out a way to conserve this ship and others like it in the area — and the world.

“The issue of ferrous material corrosion in the ocean is an international area of inquiry,” says adviser Richards. “Wooden shipwrecks, once they are buried in anaerobic settings, tend to be fairly well preserved. With iron it’s different because you have galvanic corrosion and other corrosion processes that are happening. We’ve presumed that wood is less hardy than iron, when it’s afloat. But when it’s buried, iron is undergoing these electrochemical processes.”

CORROSION AND ENCROACHMENT

Horn’s study requires him to make several visits to the Huron, and to dive on it at least once every season. He was set to dive in early January, when water temperatures should be in the mid-40s, and plans to make his final dive for the study in late spring. By then, he should have all the data he needs to start “crunching the numbers” during the summer to determine how the variables work together to affect deterioration.

On each visit, he uses a multimeter, an instrument that measures the properties of electrical circuits, in a small hole created with a pneumatic drill through the concretion into the metal. He checks for the growth of additional concretion, as well as the corrosion potential using a platinum electrode.

He’ll also make note of sedimentation. He has created a digital three-dimensional map of the wreck site. His results will be used to create a management plan for this ship, which is currently under the supervision of the N.C. Department of Cultural Resources and the Town of Nags Head.

It’s popular with divers and snorklers, located about 250 yards from the beach. The boilers, cannonball racks, propeller and rudder make it a compelling location for exploration. Preservation, however, is essential. Not only does the wreck face the natural risks of corrosion and other deterioration, there’s human encroachment as well. Sunglasses, for instance, dropped by careless visitors also disturb and corrupt the site.

Corrosion can be minimized by using sacrificial anodes that deteriorate instead of nearby ship metal, but protecting the site from human intrusion may be more difficult. Seeing the residents of Easter Island embrace their heritage may provide a suitable model, Horn says. The archaeological record is concentrated, but also cherished by the island residents.

“They take great care of their cultural heritage,” he says. It gave me a great respect for what I’m studying.” Likewise, the culture of shipwrecks — and their preservation — has integral ties with life in Nags Head and the Outer Banks.

“One of the reasons I was drawn to this field is my connection to the sea,” he says.

“At Nags Head, everywhere you look there are shipwrecks — in front of restaurants, in front of houses. The sea affects how you live your life, every day.”

This article was published in the Winter 2013 issue of Coastwatch.

For contact information and reprint requests, visit ncseagrant.ncsu.edu/coastwatch/contact/.

- Categories: