The Wilmington Port Project: Expanding Prosperity

Approaching the Cape Fear Memorial Bridge, Wilmington appears as a panorama of attractions and activities.

To the south, tourists stroll along the Cape Fear River over cobblestone lanes dating to colonial times. Historic homes. Antique shops. Upscale restaurants. And, through the windows of fashionable boutiques, visitors may catch a glimpse of rising stars in this Hollywood of the South.

Call it genteel, urban commerce.

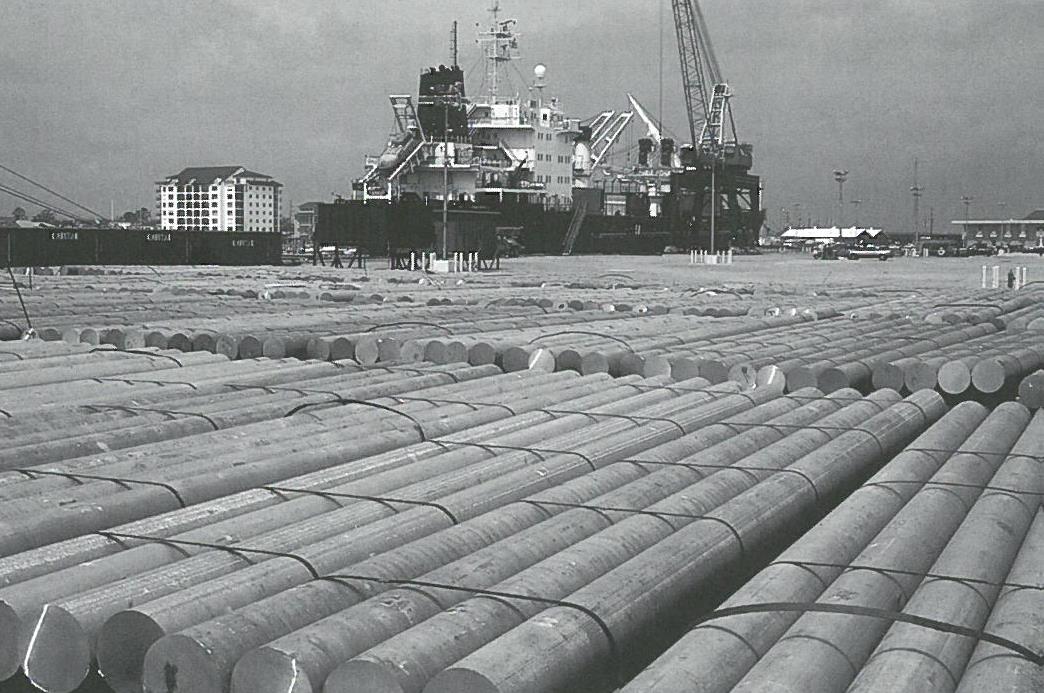

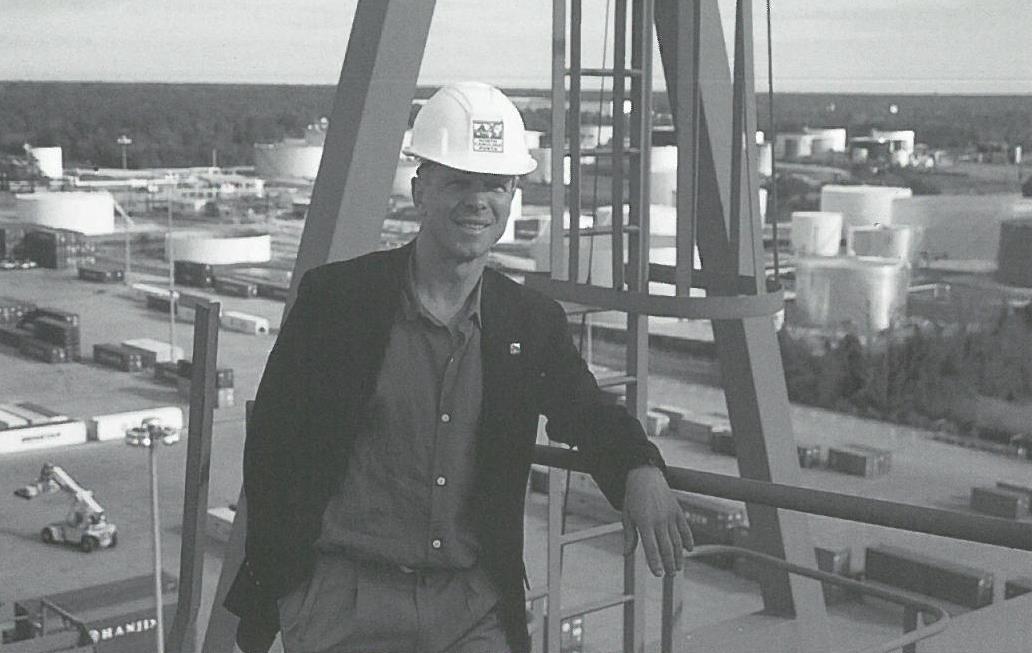

Upriver is the State Port. Erik Stromberg’s Wilmington. Dockside, the view of the Cape Fear is partly obscured by stacks of box-car sized containers. Skyscraper-tall cranes deftly move cargo on and off giant vessels flying flags from distant places. People. Trucks. Rail tracks. Choreographed motion and commotion.

It’s noisy, hard-hat commerce.

And, it’s where North Carolina industry and businesses connect with the world marketplace, says Stromberg, executive director of the North Carolina State Ports Authority since 1995.

“Statewide, over 80,000 jobs and nearly $300 million in tax revenues are generated by the state ports at Wilmington and Morehead City,” he says.

Today, North Carolina is the 10th-largest exporting state in the nation. With global trade poised for unprecedented change, Stromberg’s challenge is to ensure that the state’s dual ports capture competitive opportunities.

“Strategic planning holds the key to the future,” he says.

At Morehead City, development of recently purchased acreage on Radio Island will mean a substantial increase in berth and warehouse capacity. Last year, a 900-ton container crane was moved by barge from Wilmington to its sister port. In part, the move was in preparation for offloading scrap steel bound for a new steel-recycling mill in Hertford County.

In 1994, the Morehead City ship channel was deepened from 40 to 45 feet, allowing larger ships. Recent physical improvements to the general terminal have attracted still more commerce to the Morehead City State Port.

A Strategic Imperative

A deepwater port is crucial to global commerce. So from Stromberg’s perspective, there may not be a more strategically important economic venture for North Carolina than the five-year, $330 million Wilmington harbor deepening project.

In the coming years, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) project team will collaborate with port and state officials, university researchers, and Environmental Protection Agency scientists as the Cape Fear River navigation improvement reaches the port by 2003, and is completed by 2005.

The massive dredge operation will deepen the mouth of the channel where ships enter from the open ocean from 40 to 44 feet; deepen the upriver channel (26 miles from the mouth to the port) from 38 feet to 42 feet; and create a 6.2-mile passing lane near Sunny Point Military Ocean Terminal.

It marks the first major overhaul to the Wilmington harbor since 1964, when the Corps deepened the channel to its current depth — too shallow to accommodate many of the larger vessels in today’s shipping fleet.

Some shippers report they can’t make it upriver with a full load, and must schedule their Wilmington call when their ships are less full. Two years ago, a major international shipping company cancelled its Wilmington stop, saying that the channel was too shallow to be profitable.

It’s estimated that each additional foot of channel depth equates to $1 million per trip for shipping companies. The completed channel deepening, for example, would enable a 900-foot container ship to carry up to $12 million in additional cargo per port call, explains Stromberg. This translates to expanded export market potential for state businesses and industry — and expanded prosperity for the state — he adds.

When the multiphase harbor project began last year after years of planning, an editorial in the Wilmington Morning Star (Friday, Sept. 29, 2000) called it “A Channel to the 21st Century.” Readers were reminded: “Without a deep navigation channel, large vessels would increasingly call elsewhere, revenues would fall, and North Carolina’s farmers, foresters, businesses and taxpayers would suffer.”

Stromberg believes the project — funded mainly with federal dollars matched with state funds — is an investment that will pay dividends for North Carolina well into the next century in terms of jobs, income and tax revenues. It will give “a sharper competitive edge” to the state’s businesses and industry.

Along with the economic advantage, the deepened channel provides strategic mobilization benefits to the Port of Wilmington and to the military terminal.

Stromberg says strong partnerships — with federal and state lawmakers and agencies, with local citizens and researchers, and with the international shipping community — are essential in managing the state’s multibillion-dollar-a-day operation.

Management Courtesy of Sea Grant

Cultivating solid partnerships and building a strong professional port management team have been hallmarks of Stromberg’s career. Nationally, he has been a pioneer in developing training programs and accreditation standards for port professionals.

He cut his port management molars as a Dean John A. Knauss Fellow in 1982. The fellowship, sponsored by National Sea Grant, places top coastal studies students in executive and legislative offices to learn how science is used in the national policy arena.

As a graduate student from the University of Washington’s emerging ports and maritime transportation program, Stromberg says, “I was not your typical Sea Grant fellow. I was one of the first to do the fellowship with coastal zone management providing the umbrella for my port interests.

“During his year on the hill, he was assigned to the congressional office of then U.S. Rep. Glenn Anderson, whose California district included the mega ports of Long Beach and Los Angeles. “He paid attention to his constituents, and I paid attention to him,” Stromberg quips.

As a fellow, Stromberg helped research issues for what eventually became the Shipping Regulations Reform Act of 1984.

He also found himself, by way of Anderson, in the middle of the port development and dredging debate. The discussion led to the Port Water Resources Development Act of 1986. The hot-button question then, as now, centered on how to fund projects.

Stromberg was learning the ropes about the politics of policy while testing the waters for future Knauss fellows who would pursue interests in port and maritime policy.

Meanwhile, he set career coordinates that led him to the American Association of Port Authorities. As president and executive director, he represented all ports in the Western hemisphere. He enjoyed what he calls “a degree of success” in advancing the port development message and in establishing grassroots allies to support the interests of ports.

Critical Collaboration

If Stromberg is hoping to continue his run of success, he’s off to a good start as leader of the North Carolina Ports Authority. In the decade before his arrival, few state dollars were spent for ports’ improvements. But, in the past six years, there has been a generous infusion of both state and federal monies.

To date, more than half the funds needed for completion of the harbor project have been committed. For fiscal 2001, the feds plan to spend $65 million. And, with sponsorship from the N.C. Department of the Environment and Natural Resources, state lawmakers will add $12.5 million.

In addition, the state has contributed nearly $40 million for the ports’ capital development program.

With the funding comes increased accountability. Increased accountability also means increased visibility. And that’s okay with Stromberg.

“We want to let people know who we are,” he says. “With strategic planning we were better able to identify achievable goals and enhance the possibility of success.”

At the same time, he knows a lot is riding on the port expansion project — and he is committed to balancing the economic benefits with environmental stewardship.

That’s why Stromberg, ports environmental engineers and the USACE project team have been collaborating closely since the earliest planning stage. Based on environmental impact studies and predictive computer models, the goal is to minimize the effect on the complex river and estuarine system.

“The port deepening is the largest single infrastructure project ever undertaken by the Wilmington District,” says Corps spokesperson Penny Schmitt.

All told, 37 miles of channel will be deepened and widened and some curves straightened.

Science in the Swamp

So, what happens when you remove 27 million cubic yards of sand, rock and muck from a river bottom and redesign its course? Will pollution be unleashed from the sediments? Will there be saltwater infusion into the upstream freshwater river and swamp?

Courtney Hackney, professor of biological sciences at the University of North Carolina at Wilmington, is among the cohort of environmental scientists keeping an eye out for changes in the river. Specifically, Hackney, who also is vice chair of the N.C. Coastal Resources Commission, is studying impacts as they relate to tidal wetlands in the Cape Fear Estuary and associated rivers.

The Corps will pay about $2.5 million for the eight-year university study. The goal is to determine, beyond computer models, changes in the tidal range and increases in saltwater upstream.

“We have 11 stations from Fort Caswell to the Black River on the Cape Fear, and to Castle Hayne on the Northeast Cape Fear,” Hackney explains. Another six substations are located in tidal marsh/swamp adjacent to the river.

In addition, Hackney is gathering data from the National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration station at Wilmington and the U.S. Geological Survey station on the Northeast Cape Fear River.

Measurements are being recorded for river water and marsh water levels. In the marsh areas, researchers are looking at methane flux, salinity, and sulfate levels in soils. Salt-sensitive plants have been identified and will be monitored.

“We are in the second year of an eight-year study,” Hackney says. “It’s too soon to draw conclusions. We will collect data several years before projecting what impacts — if any — the dredging has on the upper river.”

“This harbor improvement project is meant to be a win-win situation for North Carolina,” Stromberg adds.

Expand prosperity? Yes. Sharing the wealth? Yes again.

Nearly six million cubic yards of beach-quality sand — a precious commodity for communities with tourism-based economies — will be pulled from the channel and placed on nearby oceanfront beaches. So, exactly where is all the sand going?

That’s another story.

This article was published in the Autumn 2001 issue of Coastwatch.

For contact information and reprint requests, visit ncseagrant.ncsu.edu/coastwatch/contact/.