Demographic Data Offer Insights

Visitors and residents alike often cite the continued growth of North Carolina’s coastal population. Are they correct?

Yes. And no.

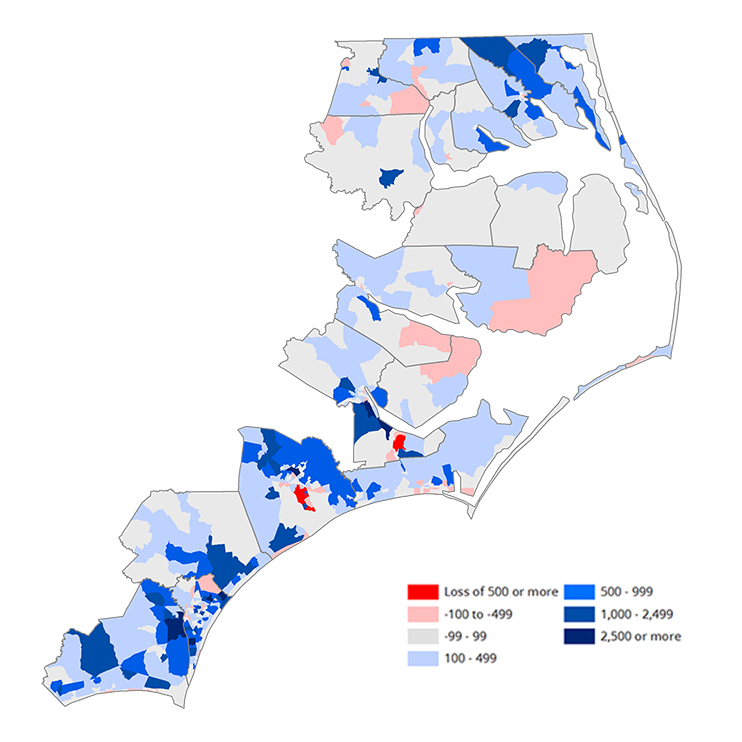

Significant differences in population trends are found across counties in the region — and even within some counties, notes Rebecca Tippett, director of Carolina Demography at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Some counties are seeing population losses, especially in young adult age categories.

“We see higher growth on the ocean shoreline,” explains Tippett, who will share her insights on coastal growth and losses at North Carolina’s Coastal Conference on April 14. The conference is sponsored by the University of North Carolina System and hosted by North Carolina Sea Grant.

Jack Thigpen, Sea Grant’s extension director, is eager not only to hear Tippett’s presentation, but also questions from those attending the conference. “This type of data is critical for discussions within coastal communities on a wide range of issues including land use, hazards planning and economic development,” he says.

U.S. Census Bureau data from 2010 to 2014 show that Brunswick County had a growth rate of 10.6 percent, giving a new tally of nearly 119,000 people. Brunswick was second only to Wake County for percentage increase. Nearby Pender County came in 10th. Its increase of 7.8 percent brought the population up to 56,250.

“Brunswick is a major retiree destination, which causes its age structure to shift relatively older. As a result, the county has experienced natural decrease, or more deaths than births. But the impact of natural decrease is more than offset by the large in-migration of retirees into the county,” Tippett noted in a recent blog.

“Brunswick was the 67th fastest- growing county in nation in 2010 to 2014,” she adds.

State officials expect the trend to continue. They estimate that by 2034, the population of Brunswick County will grow by more than 50 percent, to about 180,000.

In that same time, the state expects a growth of about 26 percent in the coastal region overall. Some counties will continue to lose residents, while others are expected to remain steady or see growth of 15 percent or less. The estimates are from the State Demographics Branch of the N.C. Office of State Budget and Management.

The census data show about 25 percent of the population in Brunswick County is aged 65 or over, compared to less than 15 percent statewide. Brunswick also has just 4.6 percent of residents ages 5 and under, compared to 6.2 percent statewide.

The “new retirees” in Brunswick County may bring higher demands for medical care and other services, including restaurants, Tippett explains. But, she adds, Florida has found that as retirees get older and/or sicker, they tend to move away to be closer to family.

Several coastal counties made a different list. Nearly half of all North Carolina counties lost population between 2010 and 2014. The top 10 in that list saw losses ranging from about 3 percent to more than 7 percent. (See tables in Tippett’s blog post on 2014 population estimates.)

“The most significant concentrations of population loss were seen in the northeastern region of the state. Among the 10 counties with the smallest growth rates, nine were located in the northeastern portion of the state near the Virginia border,” Tippett notes. “Virtually all of these counties are experiencing the combined impacts of net out-migration and natural decrease — more deaths than births — due to population aging.”

Seasons in the Sun

The lure of the ocean is a draw for many residents and visitors, but it also offers unique challenges for coastal communities.

“The census data does not capture the maximum seasonal population. For that, you need to look at housing units,” Tippett notes, citing a recent study for the Greater Topsail Area Chamber of Commerce and Tourism. The organization serves communities on and near the barrier island that straddles Onslow and Pender counties.

Tammy Proctor, chamber executive director, explains that prospective businesses often request the “summer population” statistics when considering locating in the area.

“Nobody had that information,” she recalls, citing calls to local, state and federal agencies, and other chambers in the coastal region to see if they had a reliable formula.

She posed the question to Tippett and together they tracked down various pieces of information that could feed into a calculation to come up with an estimate. The chamber now maintains a spreadsheet that can be updated when revised statistics or additional data are gathered.

“As a seasonal destination, Topsail’s population ebbs and flows over time. It’s hard to capture, but we can put clear boundaries on minimum and maximum population,” Tippett explains. “At a minimum, we have the Greater Topsail Area’s permanent population, its year-round residents captured in the census and population estimates. At the other end of the spectrum, we know how many seasonal housing units, hotels, motels and campgrounds there are, and we have a good idea of how many people they hold. This gives us our maximum occupancy capacity.”

The report estimates nearly 6,000 for the permanent population in the area. But the potential maximum would be more than 60,000 if all the vacation rentals and hotels are full and residents filled their homes with guests.

“Now we use that information all the time. I just sent it out to a prospect,” Proctor adds.

Mayor Debbie Sloan Smith of Ocean Isle Beach in Brunswick County notes her community has similar growth each summer. That fact makes balancing town services and budgets a challenge.

“We have about 574 permanent residents for eight to nine months, then 25,000 for three to four months,” she notes.

When discussions arise about community needs across the state, coastal towns often get grouped with others based on permanent population, not the prime summer season needs. “Look at our utilities and the need for water and sewer,” she says.

“All 4,000 homes need to have police patrols.”

Home/Work

Tippett also is interested in job composition and commuting patterns in the coastal region, with the latter closely tied to transportation planning.

She cites strong employment ties in northeastern North Carolina counties to the Virginia Beach/Norfolk area. Along our central coast, there are links to military bases, such as U.S. Marine Corps Base Camp Lejeune. Among southeastern counties, many jobs are focused in or near Wilmington, or across the border near Myrtle Beach, S.C.

These and other topics are on the minds of coastal leaders, Tippett notes, as she is asked to provide general talks and develop more specific projects, such as the Topsail area study.

For more information on Carolina Demography, including its blog, go to demography.cpc.unc.edu.

This article was published in the Spring 2015 issue of Coastwatch.

For contact information and reprint requests, visit http://ncseagrant.ncsu.edu/coastwatch/contact/.

- Categories: