Naturalist’s Notebook: The Rise of the Jellies

It’s a hot summer day and the beach is packed. The cool water is refreshing and inviting as many beachgoers jump in for a dip. Somewhere down the beach, a swimmer flags down a lifeguard, his leg puffy and red.

He’s been stung by a jellyfish. After getting first aid, the swimmer has a story — and some data.

Suspecting that jellyfish are increasing in waters off North Carolina, researchers are asking for the public’s help in spotting these slimy creatures around our shores.

They are seeking details for single sightings or larger events, such as when surf-zone fun on the Outer Banks came to a halt earlier this year. A swarm of sea nettles unexpectedly invaded the coastline for about four days, stinging some folks who braved the waters and keeping many others on the sand.

THE PROBLEM

Annually about 150 million people are stung by jellyfish worldwide, with some fatalities and hospitalizations, according to the National Institutes of Health.

The Charlotte Observer remarked on the increase in jellyfish stings in Folly Beach, S.C., in August where reported stings jumped from 15 to 150 in a 24-hour period. In past years, some North Carolina beaches such as Carolina Beach have flown colored flags to warn beachgoers of the slimy threat lurking in the water.

But it’s not just stings causing problems. These pulsing creatures can wreak havoc around the world, even causing power outages by clogging nuclear cooling systems in California and the Philippines.

“These gelatinous masses pose dire consequences for the environment and human activities such as fishing, shellfishing and tourism,” says Vicki Martin, a biologist at Appalachian State University.

Martin has been growing box jellies in her lab for years and is currently researching various conditions under which they grow, varying temperature, light, feeding regimes, the pH scale of different sea water concentrations and the size of the containers they are grown in.

Jellyfish are predators of fish eggs and larvae, thus they can affect fish populations and the balance of the ecosystem, Martin adds.

INCREASING POPULATIONS

Although Martin says it’s clear that the jellyfish population has been on the rise, limited data make it difficult to pinpoint why.

“It appears that a combination of manmade factors such as eutrophication of the oceans and global warming are leading to the massive blooms,” she explains. Eutrophication occurs when excessive nutrients in a body of water cause a dense growth of plant life; then decomposition of the plants depletes the supply of oxygen, leading to stress to and sometimes death for some animal species.

Several factors play a role in the reproduction of jellyfish, she adds. By tweaking certain variables in her lab, Martin finds that box jellyfish can thrive in almost any environment. For example, the normal pH of seawater is around 7.9, where 7 is considered neutral. While polyps, an early stage in the jellyfish life cycle, grow nicely at this pH, Martin’s experiments have revealed they also can reproduce and grow in the range of pH 3 to 9, showing that jellyfish can accommodate to ocean acidification, at least to a point.

While warming oceans may encourage blooms of jellyfish, mankind is helping them thrive as well. Increased coastal developments have brought docks and piers that can be attachment sites for polyps. Fishing also has depleted some of the jellies’ natural predators, such as swordfish and tuna.

“While blooms of jellyfish are not unusual from time to time, the combination of above-mentioned factors may be changing the oceanic balance to where jellyfish become dominant, thus completely changing the marine ecosystem,” Martin says.

Martin hopes that her research will help shed light on the future of jellies and their effects globally. “We need data from the field to identify numbers and types of jellyfish occurring along our coastline, to look for new exotic species that might be entering the area and better understand the conditions in the environment that correlate with a particular bloom of jellyfish.”

Throughout the year, Martin’s team will travel to sites along the North Carolina coast where jellyfish have been spotted. The scientists will measure environmental parameters, such as salinity, temperature and pH levels, and suspend plastic plates in the water column.

Researchers will check the plates quarterly to determine if polyps have attached, and will identify the type of jellyfish. High counts are a good indication of a potential bloom in the area, she says.

CITIZEN SCIENTISTS WANTED

Beachcomber scientists of all ages can join the team.

The Jelly Stalkers website, www.jellyfish.appstate.edu, brings the public into the research process. Folks who spot jellyfish can pinpoint the location of the sighting using an online map, and suggest the identity of the jellyfish species. Ultimately, the site’s data will help Martin track jellyfish movement along the North Carolina coast.

“The information gleaned will be of interest to research scientists worldwide studying climate change and the effects on the marine environment, local fishermen/shellfishers whose catch may be affected by jellyfish blooms, educational facilities such as aquariums, local schools, homeschoolers, and the thousands of tourists who vacation along the N.C. shores each year who are concerned about jellyfish encounters,” Martin explains.

The sightings should include the date, time, location, size of the jellyfish, weather and water conditions. Those making reports even can upload a picture of the jellyfish to help confirm identification.

To assist the public spotters, the website includes pictorial depictions of eight species of jellyfish common to the North Carolina coast. But the site warns everyone not to touch any jellyfish, even if it looks dried out.

Terri Kirby Hathaway, marine education specialist for North Carolina Sea Grant, cited Jelly Stalkers in a recent issue of her Scotch Bonnet newsletter because the site is beneficial to teachers, students and citizens at-large. With sightings reported by the public, researchers can gather data without actually “being there,” thus saving time and money.

It’s also important, Hathaway says, for the public to be involved in such research, especially for the coastal residents that are most affected by aquatic issues. The site will help citizens better understand science and research. A better understanding of such results means a greater interest for research in the future, she adds.

“General education of coastal residents is important so they’ll understand their environment,” Hathaway says.

“People don’t appreciate what they don’t understand, and they don’t understand what they’re not aware of,” she explains. “Awareness, understanding and appreciation provide the continuum — culminating with conservation.”

HOW TO GROW A JELLY

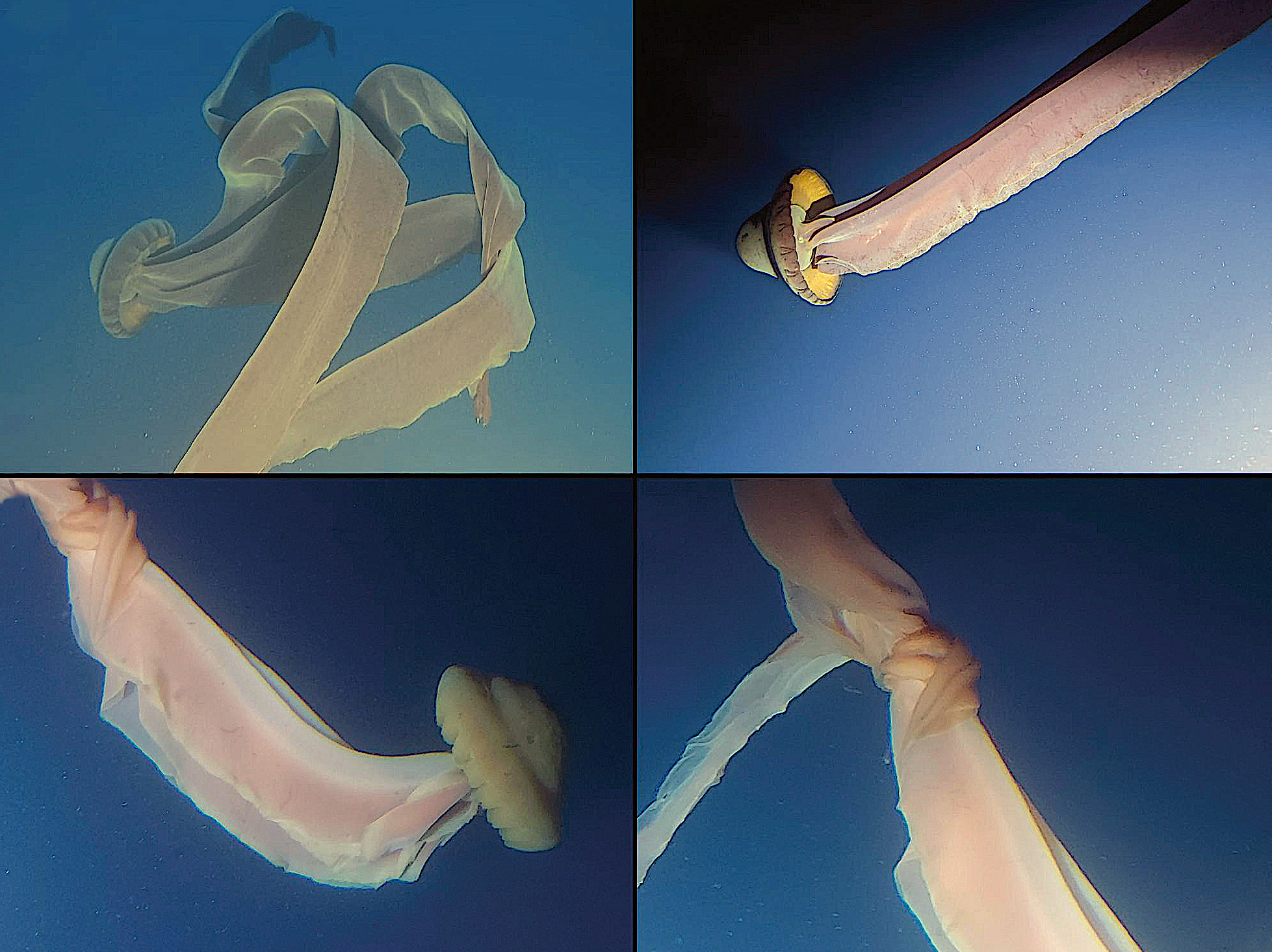

Jellyfish have two main stages in their life cycle: a polyp or an attached stalk, and a medusa, or the signature free-floating bell-shaped form. During the polyp stage, the jellyfish larvae will attach themselves to something firm on the sea floor such as rocks or shells, and gradually transform into flower-like polyps. While polyps can bud off to create new polyps, each polyp can also produce ephyrae, or larval jelly that develop into an adult jellyfish, known as a medusa.

Most jellyfish medusae move by a pulsing action of the domelike bell, and flow wherever the dominant currents take them.

Jellyfish tentacles vary from species to species. Tentacles contain thousands of stinging cells called nematocysts. Nematocysts can cause a severe rash and, in extreme cases, chest muscle spasms can occur leading to death.

Some common jellyfish found along the North Carolina coast, according to Frank Schwartz’s publication Common Jellyfish and Comb Jellies of North Carolina, are: moon jellies; purple sail; sea wasp, also known as the box jelly; summer and winter sea walnut; nemopsis bachei; sea nettles; cabbage head; mushroom jellyfish; the lion’s mane jelly; and the Portuguese man-of-war.

Comb jellies, such as the summer and winter sea walnut, and the Portuguese man-of-war are hermaphroditic, meaning they have no medusa-polyp life cycle. These jellies contain male and female cells that expel the sperm and eggs externally where fertilization occurs, according to Schwartz’s publication.

While most associate jellyfish with the uncomfortable sting, the severity of the sting can vary. Some jellyfish stings can be mild or not felt at all, according to Peggy Sloan, education curator for the N.C. Aquarium at Fort Fisher. The severity of the sting depends mostly on the species of jelly and the victim’s reaction to the toxin.

The Fort Fisher aquarium has been exhibiting jellies since 1998, after initiating the propagation in 1997. The staff is now able to provide moon jellies for the aquarium’s own exhibits as well as for other locations. While moon jellies and sea nettles are on display all the time, lion’s manes and ctenophores are sometimes displayed as well.

More information about jellyfish is available through the education programming at all three North Carolina Aquariums. To plan your visit, check out: www.ncaquariums.com.

For more information about the jellyfish research at Appalachian State University or to report a jellyfish, visit: www.jellyfish.appstate.edu.

This article was published in the Holiday 2010 issue of Coastwatch.

For contact information and reprint requests, visit ncseagrant.ncsu.edu/coastwatch/contact/.

- Categories: