North Carolina Sea Grant: Making Coastal Science Count for 25 Years

This article was published in the High Season 2001 issue of Coastwatch.

For 25 years, North Carolina Sea Grant has brought science to coastal communities — and coastal residents have offered healthy doses of common sense to academics.

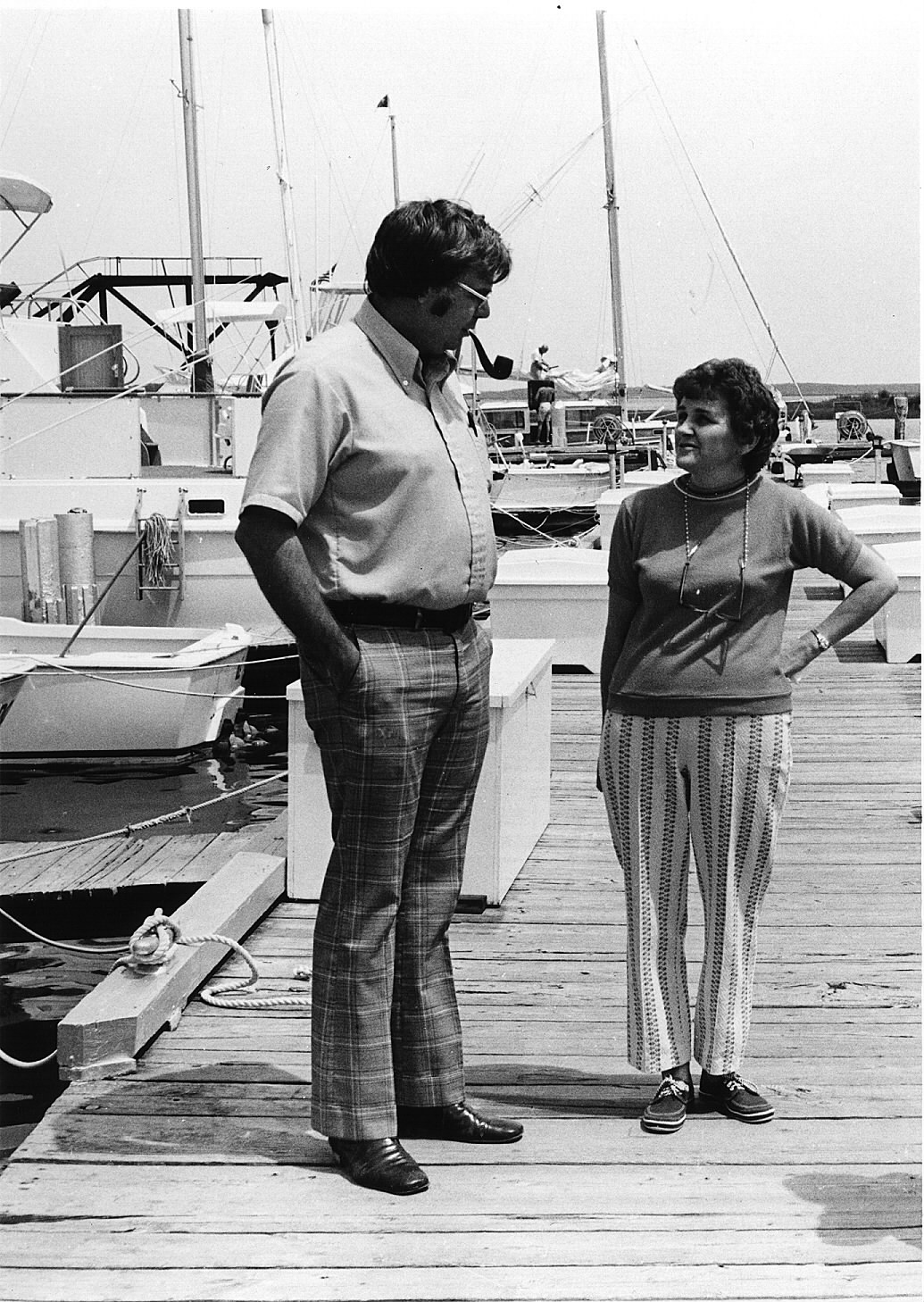

Take, for example, early efforts to gather input on research and extension needs along the coast, “I sat and talked with one man who was working his eel pots and crab pots. I talked with him for 15 or 20 minutes, making the point of asking him what we could do for him,” former Sea Grant director B.J. Copeland recalls. “He looked at me and said, ‘Sounds like you guys are just looking for something to do.'”

In many ways, that crabber was right. The infant Sea Grant program was looking to do something. Those first staffers were out to make a difference for coastal ecosystems and coastal economies.

“I got his message: They were hardworking people,” Copeland says. “To be accepted, Sea Grant would have to be relevant. We would have to deliver good information and do it when we said we would.”

As the Sea Grant program grew, extension staff and researchers would stay on the lookout for new topics and issues, especially as sleepy fishing villages became tourist meccas, and as development surged in river basins that drain from the piedmont to the estuaries.

“Sea Grant provides a direct — and personal — link between the universities and the coastal communities,” says current Sea Grant director Ronald G. Hodson.

“We have earned a reputation for being available to listen to coastal concerns and being alert to scientific and technological breakthroughs that could be potential solutions,” Hodson says.

As North Carolina enters not only the new century, but the new millennium, Sea Grant’s role will be critical to the future of the coast — and the entire state — Lt. Gov. Beverly Perdue of New Bern told Sea Grant’s 25th anniversary crowd in Raleigh.

“Our marshes, swamps, forests, lakes and rivers. Our phenomenal estuarine system and oceanfront,” she says. “North Carolina’s coast is one of the richest natural environments in the world.”

Getting Started

Mention “marine science” today, and many images come to mind. But that was not always the case. In the late 1950s, only 13 marine-related doctorates were presented across the country.

But as space exploration filled imaginations, earthly science — and in particular coastal — gained attention as well. The first proposal for a National Sea Grant program — patterned after the “land grant” universities that had developed the vast Cooperative Extension network — came in 1963.

By 1965, U.S. Sen. Claiborne Pell of Rhode Island and U.S. Rep. Paul Rogers of Florida proposed federal legislation to create a Sea Grant program. With the support of U.S. Rep. Alton Lennon from Wilmington, who chaired the House Merchant Marine and Fisheries Committee, the bill moved quickly. In less than a year, President Lyndon Johnson signed the National Sea Grant College and Program Act of 1966.

“In truth, if Sea Grant wasn’t invented in 1966, someone would invent it today. People depend on Sea Grant for good information and to help them survive,” Copeland says. “You can’t argue with priorities when they are to improve the quality of life and enhance economic opportunities. That’s what Sea Grant is all about.”

The national program — which focused on the coastal states, as well as the Great Lakes — awarded its first research grants in 1968. These included groundbreaking studies in ecology by University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill researcher Howard T. Odum.

At the same time, North Carolina officials had begun to focus on marine sciences as well. One of the last actions of Gov. Dan Moore was to create the N.C. Marine Science Council and a university-level marine science program coordinated by John Lyman at UNC-Chapel Hill.

When the National Sea Grant office requested proposals for comprehensive programs, four North Carolina campuses responded — UNC-CH, NC State, East Carolina and Duke universities. “Clearly, four programs were not going to be funded here,” Copeland says.

To solve the problem, the new governor, Bob Scott, took on dual roles — mediator and breakfast chef — in the winter of 1969. He invited representatives of the four universities, as well as state officials, to an early morning meeting at the governor’s mansion. The special guest was Bob Abel, the first National Sea Grant director.

“Part of our strategy was: Let’s do something for the state of North Carolina. Let’s forget about one institution,” recalls Walton Jones, whose marine science work included time as a top advisor to Gov. Moore, vice chancellor at NC State, and as vice president of research and public service for the UNC system. “We put the needs of the state ahead of any institution.”

Others attending the meeting included Lyman, Leigh Hammond — who worked in the governor’s office and later served in the NC State administration and led Sea Grant advisory services in North Carolina — C.Q. Brown from East Carolina, and Bruce Muga from Duke.

Jones also points to strong support from Wayne Corpening, a former N.C. secretary of administration and mayor of Winston-Salem, and Addison Hewlitt, a former N.C. House speaker who served as first chairman of the Marine Science Council.

Their efforts were successful. In 1970, North Carolina was granted a Sea Grant institutional program that worked with the various universities and was administered by Lyman’s office in Chapel Hill.

The turf battles between campuses were minimal. “The proposals were always open and always competitive,” explains Bill Rickards, former North Carolina Sea Grant associate director.

Filling Niches

Copeland, whose first North Carolina Sea Grant research was a project with NC State colleague John Hobbie that looked at nutrients in the Pamlico estuary, was named program director in 1973. This meant the North Carolina’s Sea Grant headquarters moved to Raleigh.

His goal? Full Sea Grant College Program designation — based on a record of excellence in research, extension and communication — in the minimum time, just three years.

Copeland recalls July 1, 1973, when his staff included only Rickards, who later became director of the Virginia Sea Grant program, and secretary Louise Bame. “I was told to write a proposal and submit it by August 1. We had no extension advisors and no communicators. So we set about getting the word out that we were in business,” Copeland says.

His first hires? He looked to the coastal communities and found Hughes Tillett and Sumner Midgett as the first extension agents. A few months later, writer Dixie Berg came onboard to launch a newsletter that would evolve into Coastwatch magazine over the years.

Lessie Tillett recalls how her late husband loved sharing new Sea Grant gear suggestions or techniques with his lifelong friends who had worked the waters beside him. “He loved people. They would come to talk to him,” she says.

Copeland agrees. “His focus was one-to-one. He would go find a highliner and get him to try something, then everyone else would follow.” And, Copeland adds, Tillett took on the personal mission to make sure the university folks were educated about the realities of life on the coast. “He was educating me.”

The marine advisory work involved not only finfish, but shellfish as well. “Hughes Tillett was the first Sea Grant advisor to promote shellfish culture,” Copeland recalls. “He was the first to grow clams in bags and trays. The first job he had was to get people to change the way they were doing things.”

Midgett, whose family had a long history with Outer Banks lifesaving stations, had a strong interest in land use. “They complimented each other. Between them, they were covering the activities in Dare County and beyond,” Copeland says.

The agents collaborated with Jim McGee of ECU, who was known along the coast for his short courses on various coastal topics, including bookkeeping for fishing families.

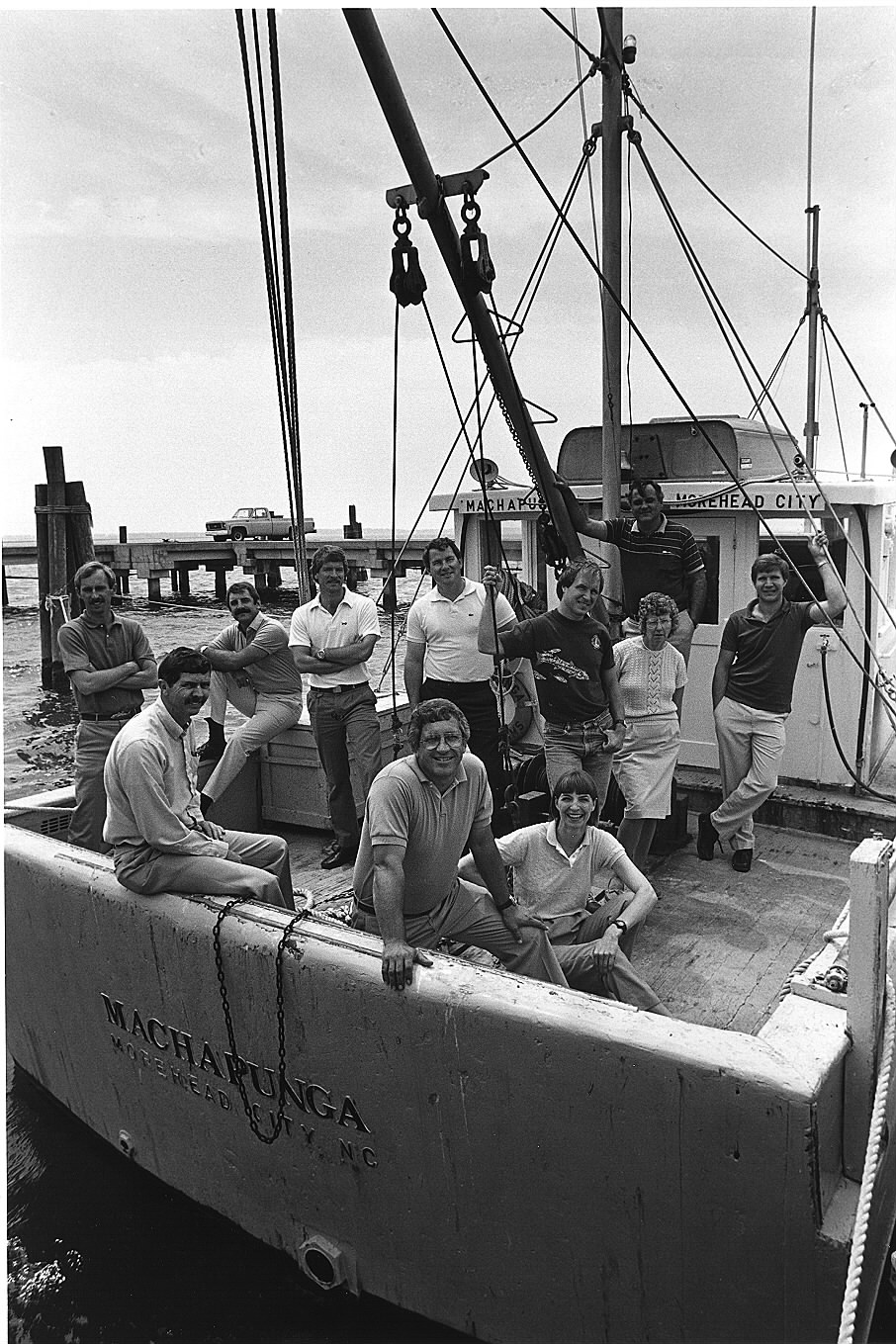

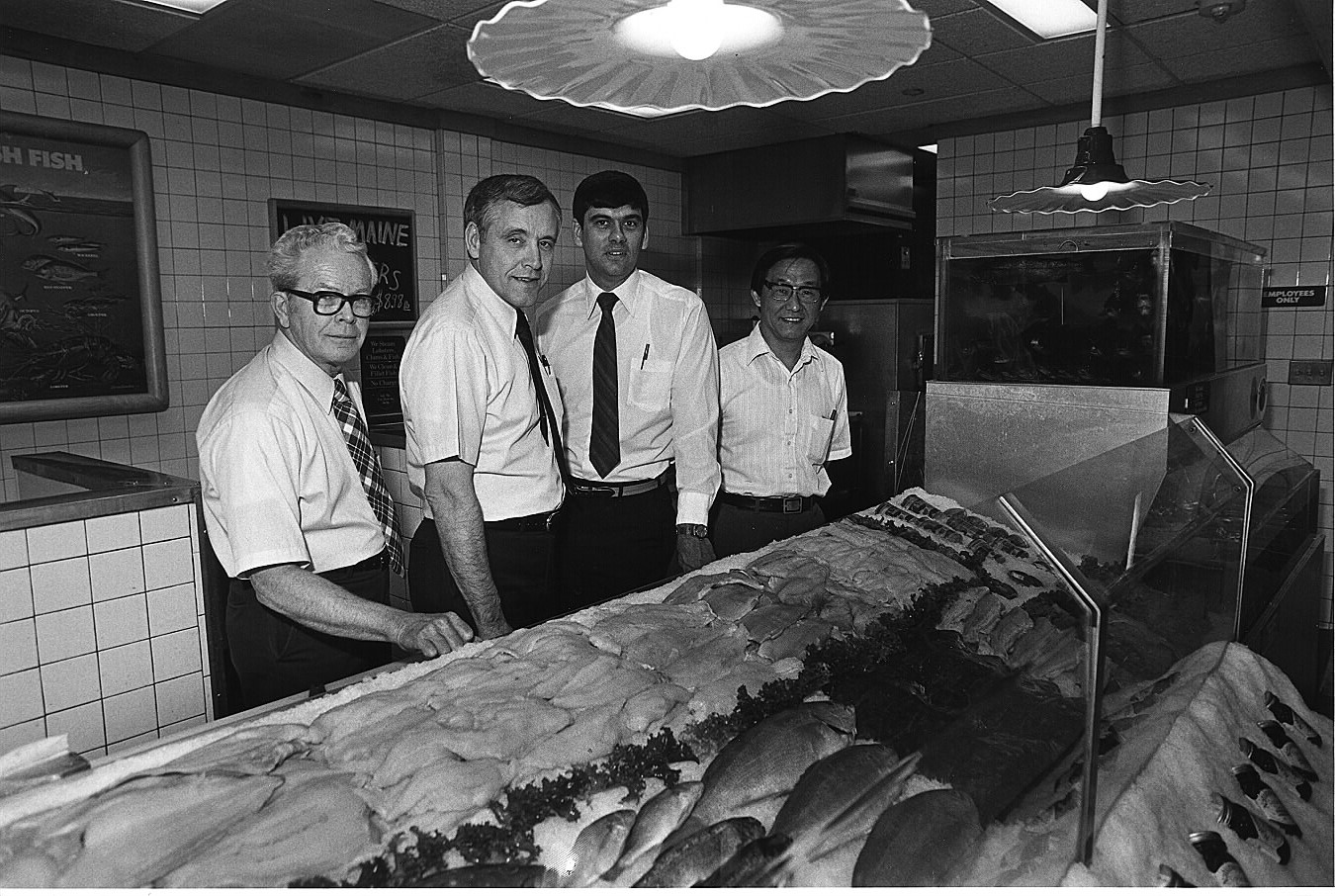

Early Sea Grant work also included efforts by Frank Thomas and Ted Miller at the NC State Seafood Laboratory in Morehead City, who worked with plant owners on a deboning machine and other seafood processing issues. Through the years, the lab had a crew of local cooks who would work diligently with Joyce Taylor to develop flavorful and healthy seafood recipes.

By 1974, Berg began a four-page newsletter and other communications products. “She wanted to get the information out to the people,” Copeland says. The first newsletter discussed market opportunities for amberjack and triggerfish and other species considered bycatch. It also profiled the seafood lab and new technology for eel pots.

And, of course, there was the research. “We were funding the best research by our outstanding faculty, who were turning out relevant results,” Copeland says.

Their efforts paid off. By 1976, North Carolina had shown three years of Sea Grant excellence. In July 1976, the program received full Sea Grant College Program status — and a new budget of $1 million.

Coastal Challenges

It was an exciting time, not only for Sea Grant, but for other coastal programs as well. The marine science centers evolved into the N.C. Aquariums. And the state was working closely with the federal Coastal Plains Regional Commission, an agency from the War on Poverty.

North Carolina’s coast, with its string of barrier islands, was beginning to see tourist opportunities — but Jones and others did not want the result to be the sprawl of Virginia Beach or Myrtle Beach.

“We wanted to be more upscale,” he says, pointing to the aquariums as attractions that could focus attention on the coastal ecosystems. “We had a concern about economic development. We wanted development consistent with the environment,” Jones explains.

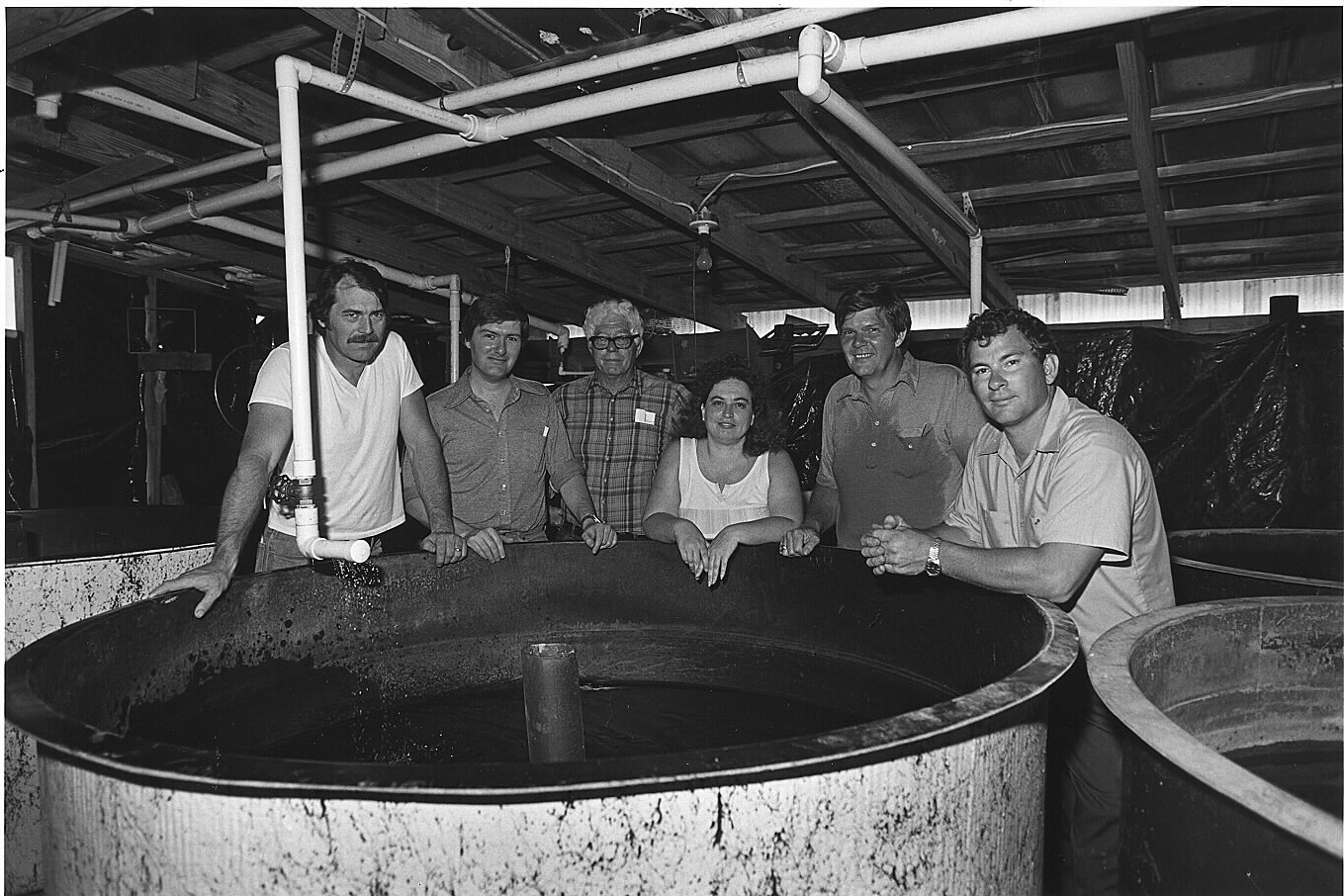

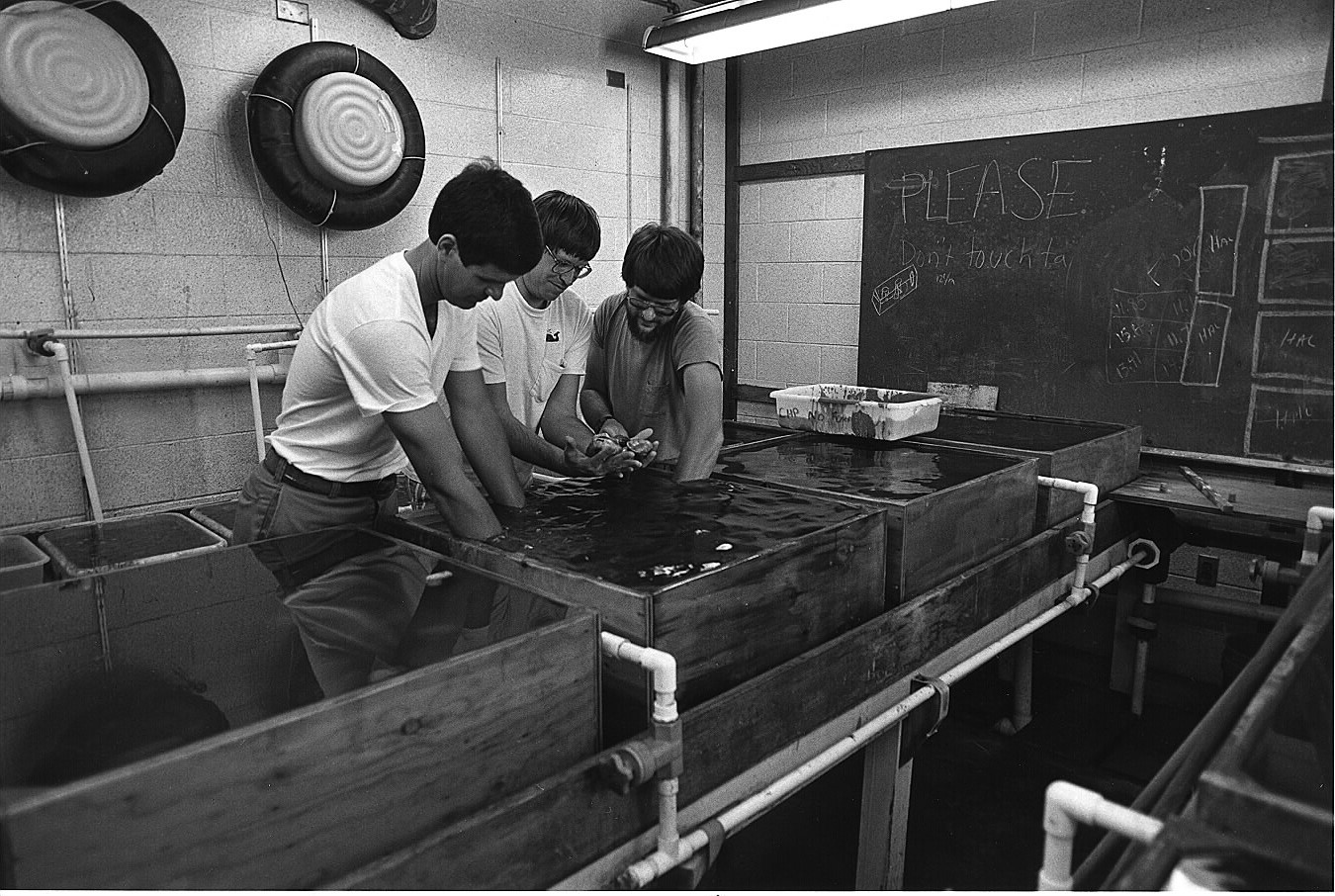

In addition, they saw Sea Grant’s applied research and extension programs as offering new opportunities for sustained economic development. Jones points to aquaculture, or fish farming. “What do you do Down East when you can’t rely on tobacco anymore? We looked at marine research as a source of employment, tourism and recreation,” Jones says. “We did some good thinking.”

And the state benefited through the years. For example, Sea Grant research led to the development of pond-based hybrid striped bass aquaculture that is now a multimillion-dollar industry that has drawn national and international acclaim. “Ron Hodson translated good science into practical husbandry that led to hybrid striped bass as an industry,” Copeland says.

Copeland, too, had the strong scientific background and could connect with the public. “He’s not only a good scientist, he is a good people person. He could talk to the fishermen. He could talk to the scientists. He could talk to the budget folks at the legislature. We all worked together,” Jones said.

Rickards recalls a reception in Morehead City. After a short social period, Copeland stood up and introduced each of the 80 or 85 people in the room. “The fact that he could do that and remember everyone is amazing,” Rickards says.

Copeland was equally adept at growing a staff. “The best thing we did is hire good people,” he says.

For example, as extension director, Jim Murray was always developing new projects. “Jim has tremendous people skills. He could get our staff to do new things and relate to clientele on all levels.”

David Duane, who monitored the North Carolina progress as a program officer in the National Sea Grant office and later served as national director, remembers the eclectic nature of the North Carolina program, including work with fisheries, dune and marsh grasses, and coastal zone management. And there was seafood technology.

“I used to chuckle about croaker bologna,” he recalls. “But they were creating products from underutilized species.”

In fact, underutilized species were the topic of a number of studies, not just in food science, but in social sciences as well. Those studies resulted in award-winning publications, a television program and countless presentations.

“The project led to a real and measurable change in people’s attitudes and behaviors towards traditionally unwanted trash fish,” explains sociologist Jeff Johnson from ECU.

A key to North Carolina’s “well-oiled machine,” Duane says, was a series of Sea Grant liaisons at various campuses, and outreach to both communities and federal agencies, including the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and the National Park Service.

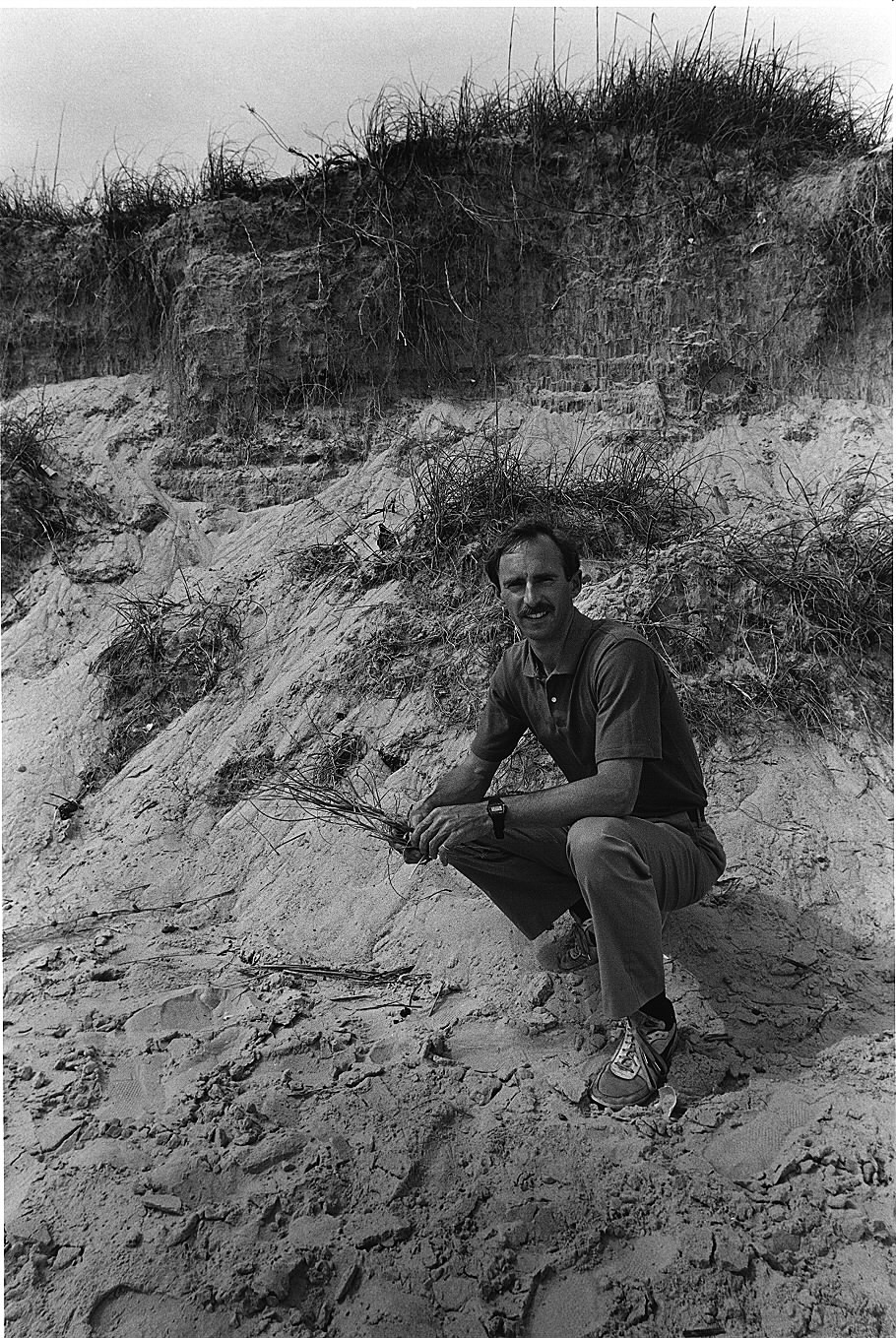

And North Carolina research work was innovative. Duane points to studies by geologist Stan Riggs of East Carolina University and colleagues who looked at the impact of ground water seeping out into the continental shelf. They also studied factors involved in coastal erosion — a big problem nationwide.

But Sea Grant is not research alone. The results must be shared with the coastal communities and the state as a whole. For example, Spencer Rogers, Sea Gran’s coastal erosion and construction specialist, worked with Riggs and others to translate research results into engineering terms that could be understood by policy makers and property owners so that they could make science-based decisions.

In fact, the Sea Grant extension program originally was known as the Marine Advisory Service — and that scientific advice, seasoned with doses of reality, resulted in many direct changes in coastal life.

Tillett was known to get calls at home late at night with questions from captains who had just come in from their boats. In a 1979 Coastwatch article, he explained why he would spend days poring over publications or calling around the country to get the answers.

“Fishing isn’t as simple as it used to be,” said Tillett, who helped introduce pot pullers and net winders. “And unless the fishermen get some help, they’re going to have a hard time making it.”

Riding the Waves

Sea Grant got off to a strong start in North Carolina — but the picture was not always rosy for the federal/state partnership that provided $2 in federal funds for each $1 in state funding.

In 1980, Sea Grant was zero-budgeted in the president’s blueprint, and North Carolina responded.

“It wasn’t a stretch to show that Sea Grant was doing good things. It was worth something — and worth keeping,” recalls Copeland, who spent many days in Washington getting the Sea Grant message out.

“A lot was at stake. You only lose once with Congress,” he says. “We passed the test with the help of Rep. Walter B. Jones, Sr.”

And it didn’t hurt to show a 1981 Sea Grant analysis that showed a 40-to-1 return on the investment. “That’s a lot of impact on people we serve,” Copeland says.

The direct impact was evident in the growth of the extension program. Initial work in fisheries and marine education, were soon joined by aquaculture and mariculture. Coastal processes work increased, as did coastal law and policy efforts.

Sea Grant’s efforts in the 1980s included the initial N.C. Commercial Fishing Show, organized by fisheries specialist Jim Bahen, and the first Beach Sweep clean-up day, organized by marine education specialist Lundie Spence. Those legacies live on today. The fishing show, now sponsored by the N.C. Fisheries Association, features dozens of vendors and workshops, including presentations by Sea Grant researchers and staffers. Beach Sweep evolved into Big Sweep, a separate nonprofit agency that sponsors waterway clean-ups in all 100 counties in the state.

And as coastal development burgeoned, Walter Clark managed to interpret the growing number of state policies meant to balance economic growth and environmental/public trust concerns.

In the 1990s, North Carolina added a new position — water quality specialist. Barbara Doll jumped in with both feet. Her storm drain stenciling and urban stream restoration efforts show the connection between growth in the Research Triangle area and coastal water quality.

Sea Grant also took on the administration of the N.C. Fishery Resource Grant Program, with fisheries specialist Bob Hines taking on the role of coordinator. By then, fisheries work included shellfish aquaculture, such as oyster grow-out methods demonstrated by Skip Kemp. Meanwhile, Wayne Wescott brought the “green stick” tuna rig to the Outer Banks, to the delight of commercial and recreational fishers alike.

Nature-based tourism was not just a buzzword, but an economic boost for coastal counties, according to surveys by Jack Thigpen, who is now the Sea Grant extension director. Seafood safety had always been a priority for processors, but federal mandates spurred training courses presented by Dave Green and Barry Nash of the seafood lab.

And when the North Carolina coast was hit by major hurricanes, Sea Grant quickly responded. Home construction and retrofitting techniques were highlighted by Rogers after Fran devastated areas such as Topsail Island in 1996. Water quality issues were highlighted in Sea Grant’s rapid response to Hurricane Floyd’s record flooding. From research to workshops, publications to media interviews, Sea Grant got the word out.

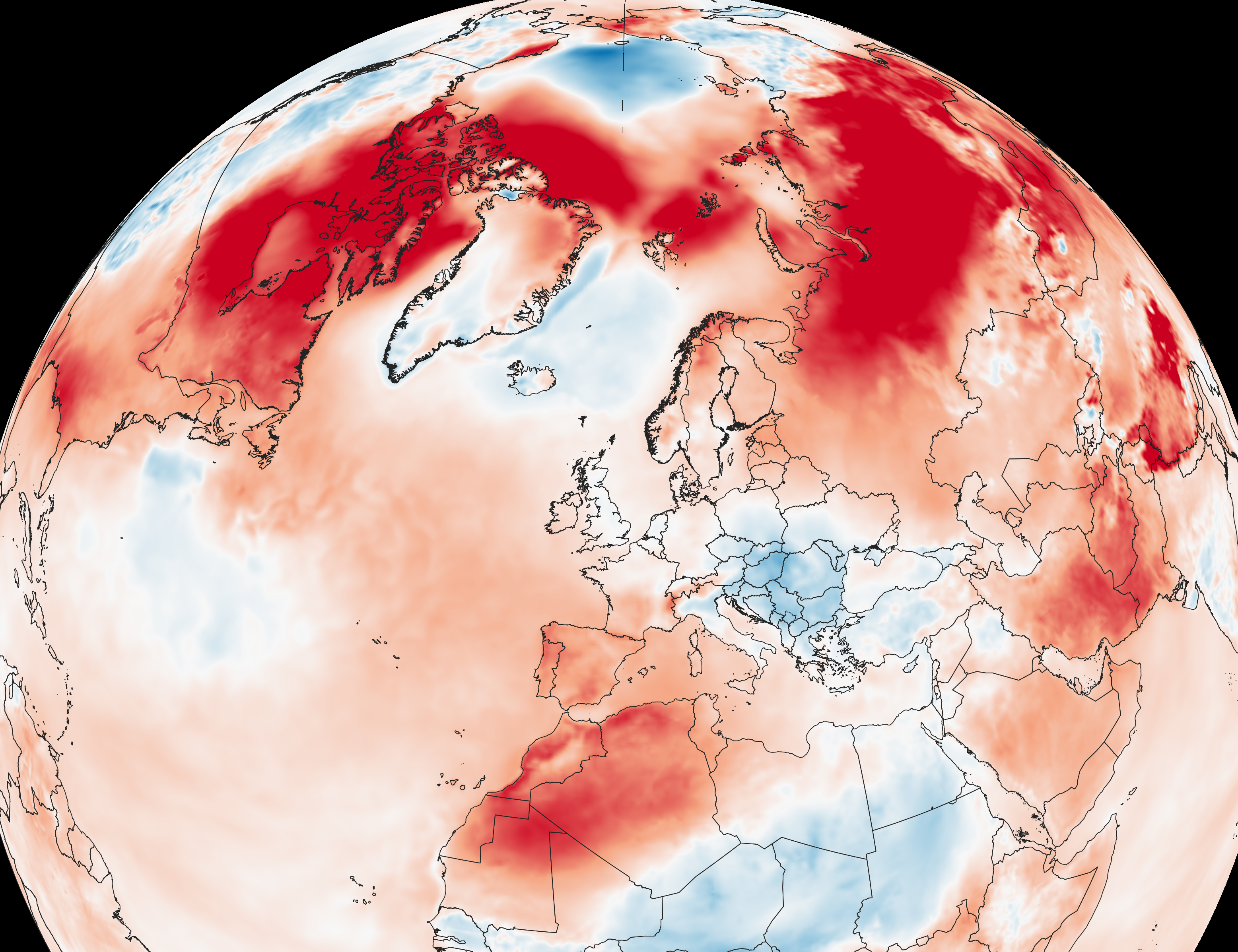

Russ Lea, vice president of research for The University of North Carolina, says Sea Grant’s decades of research background is crucial when such disasters strike. “In the wake of catastrophic climatic impacts to our coastal communities, the importance to react in a coordinated way to revitalize our coastal economy takes on considerable importance,” he says.

As we enter the new century, Hodson sees new challenges for Sea Grant as the program must be on constant watch for coastal changes wrought by humans and by nature.

“In the next 25 years, we will be challenged to continue our tradition of excellence,” Hodson says. “We must meet the needs of the diverse coastal community. These are no longer simply fishing villages.”

And, in the end, the work must be relevant. “We must maintain our connection to the people,” he says.

This article was published in the High Season 2001 issue of Coastwatch.

For contact information and reprint requests, visit ncseagrant.ncsu.edu/coastwatch/contact/.

- Categories: