Sea Grant researchers at North Carolina State University are turning up the heat on Southern flounder to produce all-female cultured stocks. The controlled-breeding method relies on water temperature manipulation during the flounder’s early development — not on genetic engineering.

From a pure science standpoint, their research results are important, since most temperature-dependent sex determination has been documented in reptiles, such as some turtles and lizards, and all crocodiles and alligators.

“From an economic standpoint, that is significant,” says Russell Borski, a zoology professor and member of the flounder research “dream team.”

The production of all-female stock pushes the Southern flounder up a notch as a candidate for aquaculture in North Carolina, he says.

Studies show that female flounder grow two to three times the size of male flounder within two years — a reasonable grow-out period for aquaculture operations. Given the high consumer demand and high world-market value for flounder, the ability to produce larger fish in a short period of time could add up to handsome investment returns.

The production of farm-raised finfish, such as hybrid striped bass, tilapia and trout, is expanding in North Carolina, according to N.C. Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services figures. But, there are no Southern flounder-farming operations that rear fish from egg to market-size here — or anywhere in the U.S. for that matter.

Japan leads the way in technology for producing farm-reared flounder. For their somewhat exclusive efforts, they are rewarded with a per fish market price of between $5 and $10 per pound — more than double the market price for hybrid striped bass, tilapia or trout.

Borski and his colleagues would like nothing better than to see North Carolina capture a substantial share of the profits from the global flounder market.

A step closer

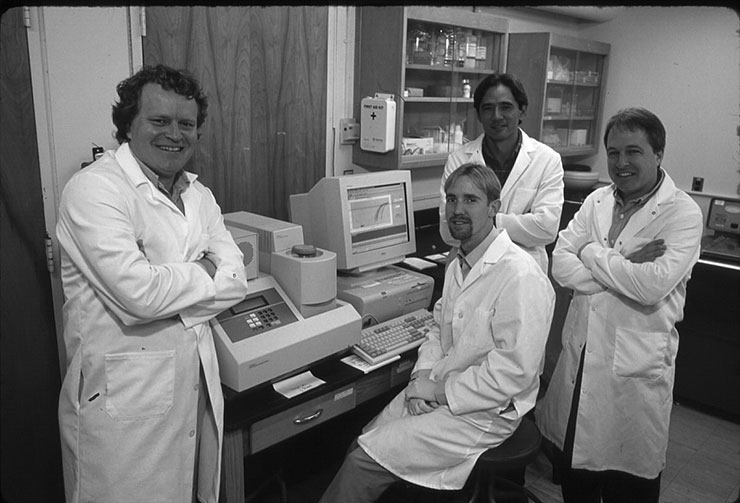

Clustered in the zoology department in the NC State College of Agriculture and Life Sciences, the team, along with Borski, includes fellow faculty members Harry Daniels and John Godwin. Adam Luckenbach, a doctoral student, has been working closely with the team for four years.

Though they jokingly refer to their work as “flounderology,” they are serious about their science and its real-world applications.

“Aquaculture can be a lucrative alternative to tobacco farming,” says Daniels, who eyes tobacco greenhouses as potential settings for growing Southern flounder in recirculating systems. Not suited for outdoor pond culture, Southern flounder do better in the warm, protected greenhouse environment.

The use of recirculating systems allays environmental concerns about wastewater discharge, Daniels adds.

Collectively, the close-knit team represents more than three decades of research experience. Their names turn up in literature reviews of aquatic research. Borski and Daniels, for example, are cited for showing that flounder can be raised in low- or no-salinity water; and Godwin, for his genetic studies of reef fish.

Daniels also is cited with Wade O. Watanabe, from the University of North Carolina at Wilmington, who worked with Daniels to develop successful Southern flounder hatchery protocols; and with Margie Gallagher, from East Carolina University, who is an expert in the nutritional aspect of flounder rearing. Their work laid the foundation for the team’s temperature-induced sex determinant research.

Another familiar name that crops up in aquaculture citations is that of Ronald G. Hodson, director of North Carolina Sea Grant. Hodson is recognized as a pioneer in advancing hybrid striped bass from the research laboratory to successful aquaculture ventures.

In describing the flounder team’s all-female stock breakthrough, Hodson says, “This research brings us one step closer to realizing profitable, large-scale aquaculture operations for Southern flounder.”

Each step takes patience, he adds. “It has taken nearly a decade to develop successful Southern flounder hatchery protocols for rearing flounder from spawning to fingerling stage. This may be the breakthrough everyone was hoping for to ensure grow-out success from fingerling to market size.”

Luckenbach says there are several advantages to a monosex female culture.

“Monosex female culture should reduce the size difference between individuals during the grow-out period, lessen mortality from cannibalism, decrease labor costs for size grading, and give a higher return on investment for feed and infrastructure,” he explains.

Solid science basis

It takes solid science to develop and implement reliable, reproducible methods, the researchers point out. Their research results have been validated with the publication of peer-reviewed articles in major professional journals, including World Aquaculture (March 2002), Evolution and Development (January-February 2003); and Aquaculture (January 2003).

The team has been invited to present their findings at the N.C. Aquaculture Development Conference in late January, and at both the Aquaculture America and World Aquaculture conferences later this year.

Importantly, their research has won respect and ongoing support from prestigious funding institutions, including North Carolina Sea Grant, the National Science Foundation, the National Institutes of Health, the National Marine Fisheries’ Salstonstall-Kennedy Program, the Golden LEAF Foundation, as well as the NC State College of Agriculture and Life Science.

Still, the researchers are not resting on their laurels, Godwin says. In the coming months, they will challenge their own science to test methods and replicate results — and perhaps even streamline and refine procedures.

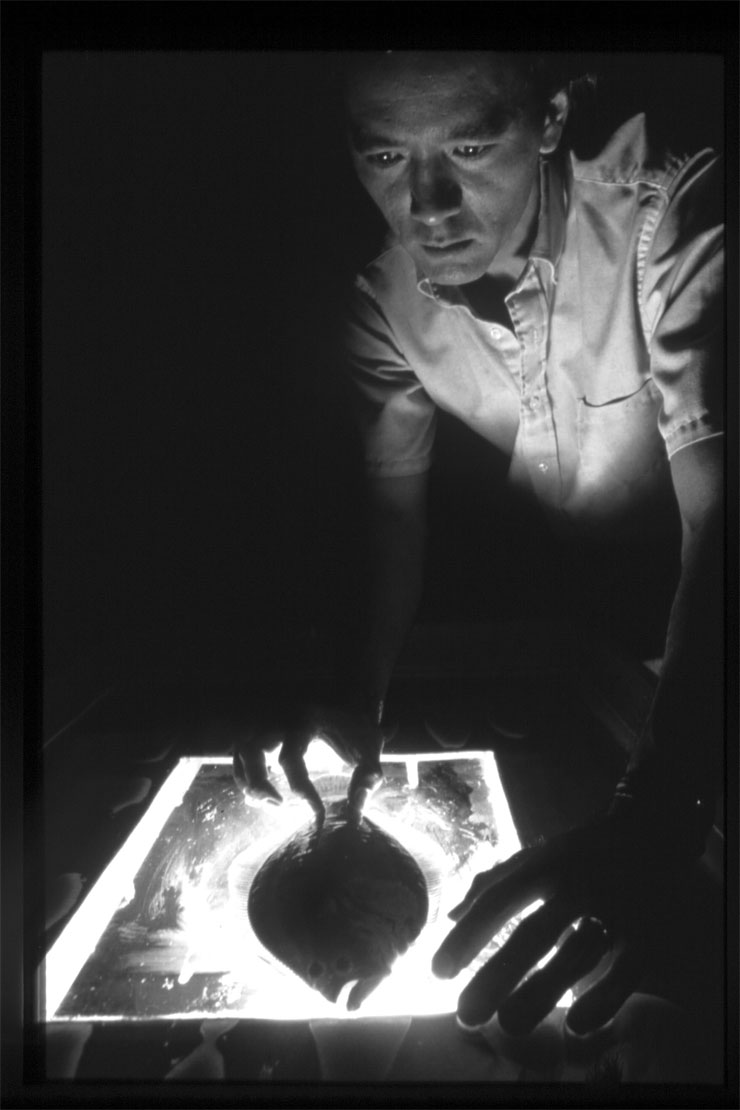

The first step is harvesting egg and sperm from wild-caught Southern flounder broodstock, using techniques developed by NC State colleagues Craig Sullivan and Hodson. Next comes fertilization and managing larval development to fingerling stage. This is where timing — and temperature — gets critical.

The team will re-examine their gynogenetic protocol to manipulate chromosomes to produce pure populations of Southern flounder XX female offspring on a large scale. They will incubate ripe eggs in ice-cold seawater to retain an extra X chromosome and then fertilize the eggs with ultraviolet-irradiated sperm (which destroys the chromosome contributed by the sperm) to produce pure populations of XX flounder.

When these fish are reared at the male-determining temperature of 28 C, XX males with functional sperm can be produced (Normal male flounder possess XY chromosomes.) These animals then can be bred with normal females to produce 100 percent female offspring when reared at the control or female-determining temperature (23 C).

The researchers will continue to probe the precise body size or developmental window of temperature-sensitive sex determination — and establish the critical body size at which temperature no longer alters the sex of the flounder.

In the coming months, they also will be considering the best methods for keeping larger fish healthy during grow out and examining the DNA of stock progeny.

Beyond economics

In the case of prospective large-scale commercial flounder farming operations, there are two sides to the economic coin. One side shows great promise as a farm-to-market economic success story. Fish farmers can provide year-round “crops” with consistent size, quality and flavor.

The other side of the coin holds economic potential for traditional commercial fishing as well. Reports of dwindling Southern flounder stocks by both national and state marine fisheries groups have resulted in more regulations and less profit for commercial fishing fleets.

In Japan, natural fisheries get a boost from the annual release of hatchery-reared juveniles.

Here, Southern flounder produced using the flounder project team protocols could be considered for stock enhancement without environmental concerns, the researchers say.

“These fish are not transgenic. We are not changing genes. They have the very same genes as their mothers,” Borski says.

While the potential for using farm-reared fish for stock enhancement may be under scientific scrutiny, it is not on the National Marine Fisheries Service’s policy agenda.

Popular fare

So, while the experts work out the most effective methods to protect and enhance fisheries stocks, there is little evidence that the demand for flounder will diminish any time soon. Health-conscious consumers are eating more fish as a protein source.

As it turns out, the Southern flounder may be too popular and versatile for its own good. Its delicate white filets have worldwide culinary appeal. The popular menu item can be dressed up as gourmet fare or served deep-fried with a side of slaw on a paper plate.

In the wild, Southern flounder share the life history “oddities” spotlight with other flatfish cousins. Most notably, their body shape changes and their eyes migrate to the dorsal side of their bodies during larval development.

Southern flounder are estuarine-dependent members of the left-eyed flounder family that includes summer flounder and Gulf flounder. Light to dark brown, they blend well into the bottom habitat they prefer. They are found in coastal waters from Virginia to Florida and in the Gulf of Mexico.

Southern flounder spawn in near-shore continental shelf waters from November through March.

Young fish enter inlets and settle on muddy bottoms in lower salinity areas of estuaries. They feed on small shrimp and fishes until they reach about eight inches, and begin to disperse into other available estuarine habitats. Capable of tolerating a wide range of salinity, they may inhabit brackish or freshwater streams.

Southern flounder are popular catches for commercial and recreational anglers alike. Consequently, the N.C. Division of Marine Fisheries has declared Southern flounder “overfished” based on recent stock assessments. The Southern flounder population in North Carolina, as reported in 2002, declined by 32 percent over the decade. A fisheries management plan is being developed.

“As a group, the flounder fishery is collapsing even with quotas and regulations. Regardless of restrictions, it doesn’t appear that we ever will get back to historic stock levels without some help,” Godwin points out.

Nature may need an assist from science. And, if stock enhancement through large-scale aquaculture does become an option, then the flounder team’s novel research approach could be a promising path to follow.

Curiosity and tenacity

But just how did the idea for developing protocols for monosex stock evolve from concept to methodology?

A good scientist is a complex animal — comprised of intellect, curiosity, creativity and tenacity. And, as Hodson suggested, patience.

As good scientists should, they began with a methodical review of the literature. They came away in awe of “how little we know about a fishery that is worth millions,” Godwin recalls. “There were data on temperature effects on sex, but the theories were not widely held or tested.”

Feeling it was worth a more thorough look, the team requested English translations of abstracts written by Japanese colleagues. It was the beginning of their age of enlightenment about the dynamics of sex determination.

In 2000, then Sea Grant Fellow Joanne Harcke traveled to Japan to learn about Japanese flounder rearing in hopes of adapting some of their successful techniques to Southern flounder culture.

Meanwhile, the research team began testing the temperature theory with a “what if” approach.

The flounder project has all the hallmarks of the triple mission of a land grant university — research, teaching and outreach.

Team members confer with premier fish scientists from around the world to share research findings and expand their own knowledge. Closer to home, they collaborate with researchers from NC State and sister universities, state and national agencies, and industry representatives.

The research project has been an educational opportunity for students, Daniels points out. Harcke, one of his students, has gone on to become a research coordinator for the N.C. Aquarium on Roanoke Island, and continues to consult internationally on flounder development.

Luckenbach has co-authored research articles published in major journals and will base his doctoral thesis on the work. He recently presented his research findings at international scientific meetings in Bergen, Norway, and Florida.

While a student at Raleigh’s Enloe High School, Jessica Beasley worked with the research team. Her accomplishments won her an American Junior Academy of Science Award in conjunction with the American Academy for the Advancement of Science. Beasley now is a student at NC State.

Sharing knowledge is an important dimension of their work. Often, opportunities come to them. This year, Aiko Ueda, a master’s degree candidate from Japan, is studying with the NC State flounder team. And visiting scientists and students from the University of Southern Denmark in Copenhagen are in residence on the main campus this semester.

Recently, officials from Indonesia on a U.S. study tour visited the fish barn/laboratory at the NC State’s Lake Wheeler Research Station.

At the Lake Wheeler facility, Daniels leads the work on refining the Southern flounder hatchery process that takes larvae to the fingerling stage. A new grant from the Golden LEAF Foundation will underwrite the construction of a building to house a flounder breeding facility. The hatchery/grow-out aquaculture complex will be the state’s first for Southern flounder.

The researchers confer regularly — Tuesday at 10 in Godwin’s lab. Thursday at 10 in Borski’s lab. And every other Wednesday at Daniels’ Lake Wheeler hatchery.

What’s the driving force? Perhaps, commitment mixed with national pride.

“The U.S. is not among the world’s top ten aquaculture producers. Japan is way up there. China is blasting us out of the water. And developing nations are leading us,” Borski says.

He and his colleagues are determined to help push the United States into a leading position in the world aquaculture market.

This article was published in the Winter 2003 issue of Coastwatch.

For contact information and reprint requests, visit ncseagrant.ncsu.edu/coastwatch/contact/.

- Categories: