LEGAL TIDES: Education, Outreach Needed for Wildlife Plan Success

Jamie Heath was a 2015 N.C. Coastal Policy Fellow. Currently, she is a planner for the Town of Williamston. Heath holds a master’s degree in geography from East Carolina University. She also has a bachelor’s degree in applied geography, with a minor in urban and regional planning, as well as a certificate in geographic information systems, all from ECU.

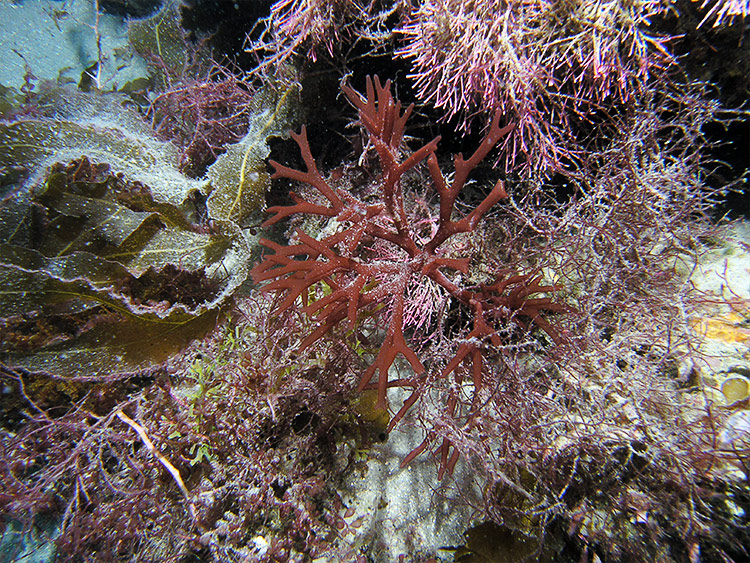

Protecting the biodiversity of an ecosystem increases its resilience and productivity, as well as expands the services and benefits it provides. Wildlife and their habitats supply us with medicines, food and other resources. These spaces also offer recreation and tourism opportunities. Wildlife habitat also provides us with advantages, such as filtering and cleaning water.

To meet these goals, the U.S. Congress requires each state to create a State Wildlife Action Plan, or SWAP. In North Carolina, the N.C. Wildlife Resources Commission, or WRC, develops the state-level SWAP.

The SWAP is designed to help coordinate state-level efforts to protect and preserve local wildlife. Overall, SWAPs enhance the states’ abilities to make management decisions regarding wildlife species and habitat conservation. The plans foster interagency cooperation and local partnerships, enhance education, and improve regulations and programs.

As a 2015 North Carolina Coastal Resources Law, Planning and Policy Center fellow — funded by North Carolina Sea Grant — I explored SWAP implementation in Beaufort, Carteret and Craven counties. One county did not implement SWAP at all, while two others used it locally. I interviewed WRC employees, local government planners and representatives of other agencies.

I chose these counties because they are using Coastal Area Management Act-approved land-use plans. This is a program, required by the N.C. General Assembly, to manage, preserve and protect the state’s coastal resources. It is important to examine how this state-level plan is being implemented locally. This is where land-use decisions are made. These decisions cumulatively add up to either protect or destroy wildlife habitat.

Local governments are given the majority of the power for land-use decision making in our country. How the SWAP is implemented locally — and whether is implemented at all — is a key element in determining whether the plan will be successful.

Public support also is a vital aspect of local implementation. Landowners exercise much discretion in how they manage their specific properties. In addition, voters elect town and country boards. Local governments involve the public in local land-use planning. In addition, a citizenry that is supportive of wildlife conservation is likely to demand that this goal is supported through land-use plans and other local regulations.

One way to raise local support is through outreach and education. The current SWAP, written in 2005, lists several options for these efforts.

The 2015 draft update, which was open for public comment this summer, names several existing WRC programs in its education activities. Many of the listed efforts focus on educating children, such as the Growing Up WILD workshops for 3- to 7-year-olds; a mobile exhibit for kids of all ages called Sensory Safari; a CATCH (Caring for Aquatics through Conservation Habitats) student workshop for 8- to 15-year-olds; and Project WILD workshops that certify adults to teach children about North Carolina wildlife.

The draft plan also lists programs for adults such as BOW, or Becoming an Outdoor Woman, to connect women to the outdoors; education programs for pet owners designed to minimize damage from pets to wildlife; and citizen science programs to involve the public in monitoring water quality and surveying species of concern.

COMMUNITY VOICES

Most of the participants I interviewed pointed to the importance of education and outreach as a way to gain stakeholder buy-in for the successful implementation of the SWAP.

“I think what helps us more than anything is public and Board [of Commissioners] education. If you don’t have the political will to make these changes, they are not going to happen,” said a Carteret County employee.

“Landscapes are impacted primarily by the individual landowner, and at the local community level more than any other way. It is often difficult to achieve conservation given this fact. That is why education and outreach programs are so important,” explained a WRC employee.

“There is a need for education of the wider public,” said an employee of Sound Rivers, a nonprofit agency that was formed by the merger of the Neuse and Tar-Pamlico River foundations.

Proper outreach and education efforts could overcome “a general lack of understanding by the wider public and elected officials on the importance of habitat conservation,” this person explained. Citizens and local leaders need to know how some decisions could affect overall community health, such as keeping some areas outside of a potential development zone, especially along waterways.

A Craven County employee expressed a need for more outreach to developers. It is possible for profit and environmental stewardship to go hand in hand “if you find a certain clientele that is wanting to live in a community where you have areas of conservation and open space. So I think if you get the word out there and you educate a little bit more, that will start catching on. And as you do that, the political bodies will say that is important.”

Local governments also had specific requests for assistance from the WRC. “We need visual depictions of the end product,” noted an employee of Carteret County. “A lot of times when you approach an individual, a community or a commissioner and you give them a verbal or written description of what you would like to see done, it is hard to receive that and process it in the brain. If you have a visual of a completed wetland, a rain garden or some similar type of improvement or conservation project, it helps impact their decision in a positive way.”

Other survey participants sought more information on marketing habitat conservation as ecotourism.

“Beaufort County’s economic future is almost surely going be tied to environmental tourism,” noted one employee. “If these can be pitched to local governments as a way to make money down the road, that is the avenue. Simply appealing to looking out for the animals’ best interests would probably not be effective. It may get you a pat on the back, but it probably won’t get anything implemented.”

Several of those surveyed mentioned the WRC’s Green Growth Toolbox, which they use to provide education and outreach to their elected officials and to the public. The toolbox shows local leaders how to balance growing communities with preserving natural and wildlife resources. The WRC already uses the toolbox to educate and assist local governments with implementing the SWAP.

Local officials requested regular updates to the GIS data in the Green Growth Toolbox. They also asked the WRC to compile information for private landowners interested in conservation easements, including more sample ordinances.

In my interviews, I found that there are groups willing to assist the WRC to educate North Carolinians about the SWAP.

“The biggest thing for us is, what are the priorities that need some action? What are the low-hanging fruits, the easy things to pick off where they might be able to use some community support to do that?” noted an employee from one nonprofit agency. “We are local and can help with local grassroots and sort of build support from the bottom up.”

The WRC has invested a lot in developing the SWAP. Putting more of a focus on education and outreach to local governments and the public would likely be the push needed to get this plan implemented through local land-use decision making, which is critical to successfully conserving wildlife habitat.

Such actions would benefit us now, as well as future generations of North Carolinians.

This article was published in the Holiday 2015 issue of Coastwatch.

For contact information and reprint requests, visit ncseagrant.ncsu.edu/coastwatch/contact/.

- Categories: