The Vanishing Oyster: Stocks Are Declining in North Carolina

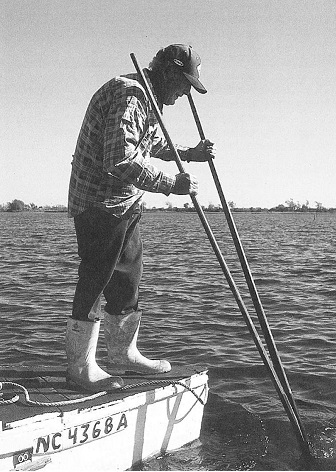

While the tide is low on the Newport River, Garry Culpepper trudges through muddy water to a large oyster rock on a nearby shore.

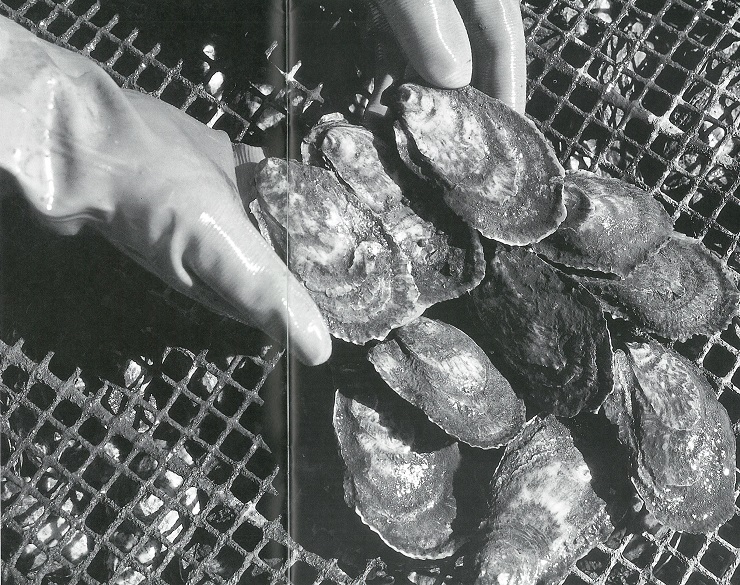

Dressed in black boots and gloves, Culpepper bends over and picks up a large oyster shell. “This is a rock oyster,” he says. “It is nicely round and fat. This is what you used to find all around the Newport River.”

Now Culpepper — one of the last hand-harvesters of oysters left in the state — has to settle for a small coon oyster that is thinner and less meaty than the rock oyster.

“I don’t work this shore,” he says. “I go to more productive areas. You would probably work this area hard and only get one bushel. Since we lost the Cross Rock in the Newport River, we have been forced to work the river near the ocean inlet and settle for coons. It is not a high-grade oyster.” The rock was closed to harvesting because of pollution.

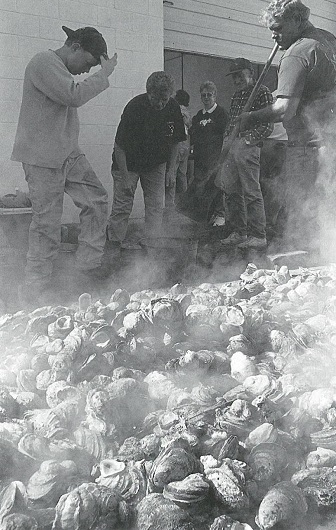

While Culpepper is laboring in the river, many of his neighbors are steaming oysters on a gas grill for the Mill Creek Oyster Festival. For the past 26 years, the festival has celebrated the delectable oysters harvested on the Newport River. Each year, people flock to the festival to get bowls of steaming clam chowder and plates full of fried seafood and steamed oysters.

There’s only one problem: the oysters don’t even come from the Newport River.

“These oysters are from Mississippi,” says David Knox, the festival organizer.

“We have been getting oysters out of state for eight years. We get about 200 bushels for the festival. It is hard to get anyone around here to guarantee that many oysters.”

The vanishing oysters on the Newport River is a familiar scenario in other North Carolina rivers and creeks — from Harlowe Creek in Carteret County to Lockwood Folly River in Brunswick County.

At the tum of the century, North Carolina produced almost two million bushels of oysters a year. By the 1920s and 1930s, annual production had declined to about 300,000 bushels. In 1998, 44,613 bushels of oysters were harvested in North Carolina compared to 225,000 bushels in 1987, according to the N.C. Division of Marine Fisheries (DMF).

”From 1900 to 1945, ovemarvesting and harvesting methods had a lot to do with the decline of the oyster industry,” says Mike Marshall, DMF central district manager. “After 1988, Dermo (a naturally occurring parasite) has greatly affected the oyster industry. In between, there has been a lot of habitat loss and water quality has been affected.”

To address the oyster crisis, the N.C. Blue Ribbon Advisory Council on Oysters was initiated in 1992. The recommendations included more support for mariculture or fish farming. North Carolina Sea Grant has been on the forefront of educating fishers about mariculture techniques.

The council also addressed protecting and resto1ing oyster habitats; improving coastal water quality and developing disease-resistant strains.

Though few of the recommendations have been implemented, they are being considered by the DMF for the long-term oyster management plan. The Fisheries Reform Act of 1997 mandates that the state establish management plans for oysters and other major fisheries.

“The plan will be finished in October 2000,” says Marshall. “One of the most important parts of the plan is managing oyste.rs around diseases. Another controversial issue is using non-native species in North Carolina waters.”

The public information document, which came out in September, recommends stock assessment of oysters.

The state has good data on commercial harvesting of oysters, according to Marshall. “However, we are not going to get an accurate picture of oyster harvesting data until we get a program in place for recreational harvesting. It is particularly important in the southern part of the state. Anybody, including those who live outside the state, can take a bushel of oysters per day for consumption during the open harvest season.”

Marshall says fishers also voice concerns about the state’s leasing programs. N01th Carolina has 295 shellfish bottom leases for oysters and clams covering 2,204 acres, according to the DMF. About 500,000 acres are suitable for cultivation.

The two top oyster-producing states in 1998 — Louisiana and Washington — have culture or lease systems. Louisiana has 403,000 acres in private leases. Washington allows a non-native species, Crassostrea gigas, to be cultured on private leases, significantly increasing production. Connecticut, which ranked fifth in overall production in 1998, has 30,146 acres leased for shellfish.

Even though leaseholders in North Carolina have posted signs in the water, the state doesn’t offer much protection against poachers.

Jim and Bonnie Swartzenberg, who have several leases scattered across Stump Sound near Topsail Island, have had problems with recreational fishers using their beds.

“Some people get the idea that everything is free,” says Jim Swartzenberg, who owns J&B AquaFood in Jacksonville. “They don’t care about our leases. They think they can wade out and help themselves to our oysters.”

As the state develops its management plan, Culpepper and other fishers have numerous ideas on reviving the industry.

“For oysters to be productive and come back in North Carolina, you can’t rely on Mother Nature,” says Culpepper. “I would like to see the state do more seed planting. The Division of Marine Fisheries is loaded with biologist5 who could spawn oysters and transplant the seeds.”

Oyster Valuable to State

The American oyster (Crassostrea virginica), which can survive the often harsh and constantly changing conditions found in North Carolina’s rivers and sounds, has an important place in the state’s estuaries. Healthy oysters serve as a natural water-filtration system by cleansing estuaries of suspended materials, taking up excess nuisance algae and promoting growth of vegetation.

They also create a productive habitat for aquatic life, including blue crabs, shrimp, speckled sea trout, drum and rockfish, and serve as a stabilizing force in the estuaries’ sediments.

“The health of North Carolina’s oyster population is a good indicator of the overall health of our estuaries, and all prudent measures should be taken to ensure a viable oyster resource,” the N.C. Blue Ribbon Council report states.

Since before recorded history, the oyster has been an important source of food in coastal areas. When the first Europeans arrived, they were amazed at the number of oysters found.

The Carolina oyster industry hit its ascent in 1880s when Baltimore companies built large canneries in coastal towns. Schooners from outside the state crowded the state’s oyster beds. They overwhelmed the industry and introduced oyster dredges and longer, sturdier tongs into the local oyster industry. Despite later attempts to restrict dredging, most of the damage to oyster beds already had occurred by 1910.

The state’s oyster stock began declining from its peak around the tum of the century to today’s low harvests. For years, many families along the coast made a living from oyste1ing and shrimping.

In North Carolina, the oyster is found from the extreme southern end of the Albemarle Sound southward through the state’s sounds and estuaries to the South Carolina border. The most productive counties are Carteret and Onslow.

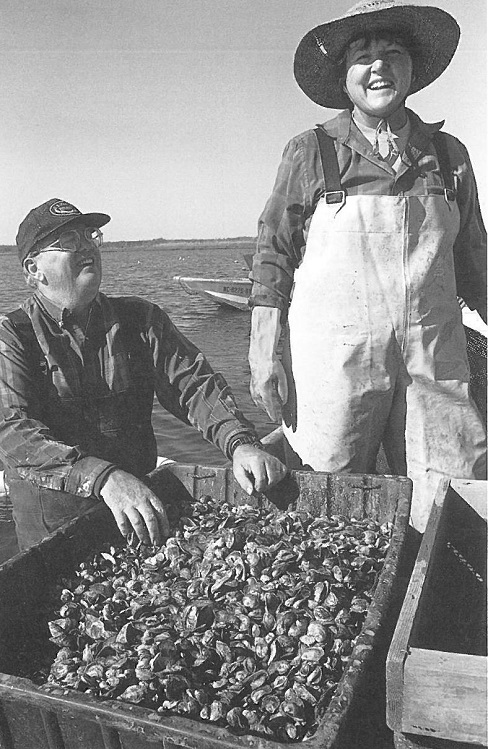

Bill Rice, 87, remembers when 100 families around Stump Sound made a living from hand harvesting or tonging for oysters.

“When I came here in the ’40s, everybody who lived here all caught oysters for a living,” says Rice. “If someone got sick, everyone else would help to pay the doctor’s bill.”

Back then, he says, each person had his own private area for harvesting oysters. “You would catch 10 to 17 bushels a day. You didn’t poach on other people. Everybody was happy in the oyster business.”

Now, Rice and his family are the only Stump Sound fishers left in the oyster business.

During the oyster season, Rice and his wife Bernice get up at sunrise when the water is clear to get in their skiff and tong for oysters. They often accompany their daughter Bonnie Swartzenberg and her husband Jim in the sound. Bonnie and her mother use tongs to fill their baskets while Bill and Jim nub the clusters and cull out the dead shell and undersized oysters.

“Bonnie’s mother is the champion of tonging,” says Jim Swartzenberg.

“Bonnie and her mother can outdo me.”

Rice says that oysters have made a big difference in his life. “Of my seven children, two have Ph.Ds, three have master’s degrees and two others have bachelor’s degrees. Harvesting oysters (along with farming) gave me added money.”

In the 1960s, ecological changes began affecting oyster harvests. Insidious intrusions —disease and polluted waters, combined with poor management and overexploitation by the oyster fisher — have tainted this once prolific resource.

Since the late 1980s, Dermo has been responsible for major oyster kills in North Carolina. Harmless to humans, the parasite wears down oysters over many months and kills them before they reach a harvestable size.

“The most damage in North Carolina from Dermo has been on the Pamlico Sound where conditions are conducive to the proliferation of parasites,” says Marshall. “Typically, a high salinity in the water and above average temperatures allow the parasite to reproduce in high numbers. If you look back over the last 100 years, 90 percent of the oysters landed in North Carolina have come from the Pamlico Sound.”

Over the past years, there also have been isolated incidents of MSX — a parasite that typically tluives in cooler waters north of North Carolina.

A combination of factors has forced the closing of many oyster beds. Of 1.43 million acres of No1th Carolina salt water suitable for shellfishing, more than 56,000 acres of shellfish-growing waters are permanently closed, according to a DMF report. This represents an increase of about 380 acres since 1998.

Most normally open areas from Carteret County southward also experience temporary closures during excessive rains. They are reopened for shellfishing once water samplings indicate bacteria levels are safe.

Outside Gene and Lillie Oglesby’s Mill Creek home on the Newport River, the state has closed a large man-made oyster rock dubbed “Shell Road” because of the large number of oyster shells.

”I have eaten many an oyster from Shell Road,” says Lillie Oglesby. ”Now the whole river is polluted from Newport to Lawton Bay.”

Oglesby’s daughter, Elaine Crittenston, vividly remembers the day when the state closed one of her dad’s prime oyster gardens.

”My dad had tended the oyster garden in the area that was closed,” she says. ”He had nowhere to go to get clean oysters. I remember seeing tears in my dad’s eyes.”

Not too long after that, Gene Oglesby retired from oystering.

“It got to the place where there was nothing out there,” he says. “You would work all day and would have done good if you caught a bushel.”

To provide more oysters, the state initiated an Oyster Relay Program. Fishers are paid to bring shellfish from polluted waters back into clean waters. There the oysters purify themselves before being harvested the next season. Leaseholders also are allowed to move these oysters to their beds at no cost.

From April to mid-May, the Swartzenbergs and Rices load up their boat with small cluster oysters from state-managed beds in polluted waters.

“We take up about 60 bushels of clusters of oysters at a time and then relay them to our leases,” says Swartzenberg.

With the decline of the oyster business, shucking houses also vanished. Today, there are no shucking houses operating in Mill Creek. The last one closed in 1985. The vacated building “stands alone on the river as a reminder of the ways things used to be,” says Garry Culpepper’s mother, Johnise. “When I was growing up, there were five shucking houses in Mill Creek. My dad had one house.”

She remembers when Hurricane Hazel roared through Mill Creek on Oct. 15, 1954, and damaged the shucking houses.

”Many of the houses were hurt bad,” says Johnise Culpepper. “But my dad’s own house had minor damage. Others in the community pitched in to fix his house. Instead of nine people shucking oysters, he had 20 workers because so many people were out of work and needed the money.”

Aquaculture is Wave of Future

To increase oyster production, some fishers are turning to aquaculture. The methods for culturing oysters vary — from growing oysters in racks in the water to new seeding methods. The traditional method of oyster culture is the planting of cultch material (shells, etc.) to provide a clean, firm space for the attachment of natural larvae.

“The future of the oyster industry is in mariculture,” says North Carolina Sea Grant mariculture specialist Skip Kemp. ”In order to harvest, you need to put seed in the water. Harvesting from the wild relies on natural seed, which is limited.”

Sea Grant and Tipper Tie, Inc., a metal clip manufacturing company in Apex, developed an innovative method of culturing oysters off the bottom with a grow-out system that resembles a floating ladder. Now a few oyster growers in the state use this method to grow shellfish.

Swartzenberg was one of the first to try this chub method and received a state Fisheries Resource Grant to determine its economic feasibility.

He also uses racks to grow oysters. In a leased area of Stump Sound, he has more than 800 cages strapped to rocks. Each cage holds about a half bushel of oysters.

“Racks fare better in storms than chubs,” he says. “A whole set of chubs flipped over during Hurricane Fran, but the racks have withstood the ravages of the past four hurricanes.”

Both methods of growing oysters lead to a ”fuller and cleaner oyster and more money,” says Swartzenberg. “That is not to say you don’t get a clean oyster from the bottom. But for cultured oysters, you get a better price.”

Although cultured oysters bring a higher price, he says it is more labor intensive than growing oysters on the bottom. “When you have oysters on the bottom, you don’t have to move them during a storm. The bottom line though is that the cultured oysters are more of a sure thing. The bottom oysters are more apt to die from disease.”

Mark and Penny Hooper of Hooper Family Seafood in Smyrna receive 20 percent of their income from mariculture.

They have experimented with the cage-and-rack and chub methods to grow oysters. In recent years, they have received Fishery Resource Grants to test the methods.

”I have found that the method doesn’t matter,” says Mark Hooper. ”The seed determines how successful the oyster crop is. We get our seed from hatcheries — brood stock. Some perform better than others.”

Hooper has a lofty goal: producing the perfect oyster. “I would like to produce a single oyster of similar size. It needs to be rounded and deep. If I was able to produce a nicer oyster, I could sell it to upscale restaurants in the Triangle.”

Leslie Lee of Sloop Point Seafood on Topsail Sound is testing new ways to seed oysters. He spats the oysters from seeds in bags or shelves. Then he lays them on top of a screen on a muddy bottom.

“We are just getting into it,” says Lee. ”They are looking great, but I have only been doing it for a year.”

Oyster Research Underway

While aquaculture techniques are being used on oysters, research is under way in North Carolina to test methods to enhance management of native oysters and the aquaculture potential of non-native oysters.

Charles Peterson of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill’s Institute of Marine Sciences is studying the structure and hydrology of oyster reefs — critical areas for oyster production. For example, by manipulating the profile of oyster reefs, water or current flow may be sped up, possibly helping these filter feeders grow faster and avoid disease.

”We are looking at how oyster gear and dredging has damaged oyster reefs,” says Peterson, a North Carolina Sea Grant researcher. ”We have looked at alternative techniques for harvesting oysters and addressed oyster growth and mortality. We have found that oyster growth and survival improved by installing larger reefs than traditionally have been constructed by the Division of Marine Fisheries.”

Recently, Peterson received a $200,000 grant from the state to test the aquaculture performance of non-native oysters in North Carolina waters. At least two of the species are naturally resistant to Dermo and other diseases that plague the state’s native oyster.

Research on oyster disease also has gained momentum in recent years. At Rutgers University in New Jersey, oyster breeding programs have resulted in stocks resistant to both Dermo and MSX. These stocks have been evaluated in growth and survival trials in the Delaware and Chesapeake bays, but none of the stock has been tested in North Carolina waters.

”This area is pretty much wide open to research,” says Ami E. Wilbur, assistant professor of biology at the University of North Carolina at Wilmington. ”North Carolina needs to generate its own disease-resistant stocks to combat its particular problems with the health of local oyster populations.”

Wilbur sees great potential in the state for more research on selectively bred oysters for consumption and restoration.

“North Carolina has the waterways to support a lot of oyster culture, and considerable interest in restoring previously productive areas,” says Wilbur. “It is exciting to be a new professor in the state because there is a lot of opportunity to get involved in a variety of different projects.”

This article was published in the Winter 2000 issue of Coastwatch.

For contact information and reprint requests, visit ncseagrant.ncsu.edu/coastwatch/contact/.