A Sturgeon Primer

Chuck Weirich is North Carolina Sea Grant’s marine aquaculture specialist. He has a background in culturing finfish, including Russian sturgeon.

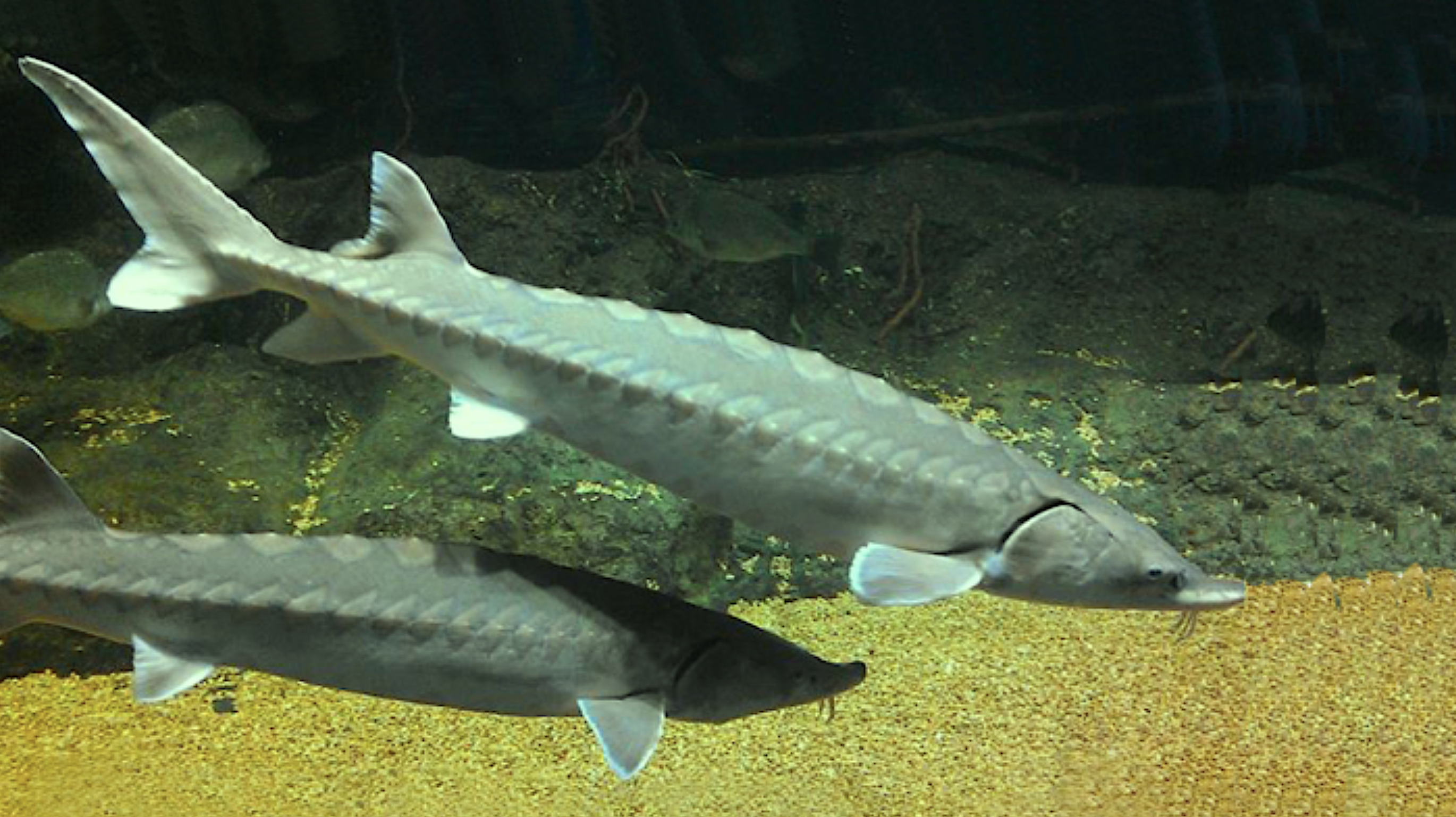

Sturgeon are among the oldest living species of fish. Their fossil records date back more than 150 million years.

There are 26 species of this prehistoric fish, from the taxonomic family Acipenseridae. Eight are native to the United States: the white and green sturgeons of the Pacific Coast; the lake sturgeon of the Great Lakes region; the shovelnose, pallid and Alabama sturgeons of the Mississippi River basin; and the shortnose and Atlantic sturgeons of the Atlantic Coast.

Sturgeon have distinctive elongated bodies, lack scales and can grow very big. They range in size from 7 to 12 feet and can weigh in excess of 100 pounds. Several species have lifespans of 80 years or more. Female sturgeon are slow to mature sexually and, depending on the species, may not begin spawning until their second decade.

Most sturgeons are anadromous: Adults live in coastal waters and migrate up freshwater rivers to spawn. They seek deep water, strong current and a stone or gravel bottom. At spawning, females release tens of thousands to several million eggs, fertilized by sperm released from males. Fertilized eggs become very sticky and adhere to the stones or gravel on the stream bottom, where they incubate.

Larval sturgeon — also called fry — hatch in about five days at a water temperature of 70 F, and about 10 days at 50 F. After hatching, they get nourishment from a yolk sac that can last as long as two weeks.

After the yolk sac is absorbed, fry begin feeding on zooplankton, eventually moving on to progressively larger prey, including worms, crustaceans and mollusks. Like adults, juvenile sturgeon are bottom feeders. They have extendable sucker-like mouths on the lower part of their bodies, lined with taste-sensitive barbels, or feelers, to locate food.

Most species of juvenile sturgeon remain in fresh water for several years before making their way to coastal waters where they reside as adults. Eventually, they return to fresh water to spawn.

STURGEON AQUACULTURE IN NORTH CAROLINA

Several sturgeon species worldwide are prized for their roe, also called caviar, and meat.

In the late 19th century, a substantial commercial fishing industry targeted Atlantic sturgeon in North Carolina. In fact, so much caviar and meat were harvested in the state that railcars hauled the product to markets in New York City every day. The aptly named Caviar City in New Jersey served as a distribution center.

However, overfishing and habitat destruction have severely reduced the population of Atlantic sturgeon. Today, it is listed as endangered — a status shared by a number of other sturgeon species worldwide.

Regardless, demand for caviar and sturgeon meat has remained steady, leading to a surge in sturgeon aquaculture over the past few decades. Today, sturgeon are cultured in countries such as China, Russia, Italy, Bulgaria, France, Israel, Uruguay, Iran and the United States.

Aquaculture operations in the U.S. grow white, Siberian and Russian sturgeon. Presently only two operations in North America are rearing Russian sturgeon, both located in North Carolina. They are Atlantic Caviar & Sturgeon Company in Lenoir and Marshallberg Farm in Smyrna.

Russian sturgeon are prized for producing Ossetra caviar, considered second only in quality to the famed Beluga caviar.

Currently, Atlantic and Marshallberg receive annual shipments of imported fertilized Russian sturgeon eggs from Europe. However both operations are in the process of establishing breeding programs to produce sturgeon eggs and larvae domestically.

The farms use recirculating aquaculture systems to raise sturgeon. These systems capture effluent from the tanks and repurpose it for agricultural use. Monterey Bay Aquarium’s Seafood Watch has listed sturgeon raised this way as a Best Choice Seafood Product for the method’s sustainability and low impact on the environment.

When fish reach a size of approximately 10 pounds — after about three to four years — females are separated from males. The females then are grown further until they are ready to be harvested. This normally occurs when fish are at least 20 pounds, and are between 5 and 8 years old.

Before they are harvested, females are sampled to assess egg quality. Those that have high-quality eggs are placed in holding tanks for a month to preserve the flavor of the resulting caviar. The eggs are sampled again the day before processing to determine which fish are ready for harvesting because egg quality might have changed.

The caviar is retrieved from the female’s two ovaries, or egg sacs. During this process, individual eggs are separated, rinsed and drained. The caviar is mixed with salt before the final product is placed in a metal tin, weighed and refrigerated until it is sold.

Ovaries account for approximately 10 to 20 percent of the total weight of each female. A 20-pound female will yield between 2 and 4 pounds of caviar. At current wholesale prices, one fish can produce between $1,000 and $2,000 worth of roe.

Males are harvested on an as-needed basis to supplement meat sales. Meat products of male and female fish are bullets — gutted, headed and fins removed — and fillets, which are sold fresh or frozen. Sometimes, the fillet meat is brined and smoked to create smoked sturgeon, a highly regarded, value-added product.

This article was published in the Spring 2015 issue of Coastwatch.

For contact information and reprint requests, visit ncseagrant.ncsu.edu/coastwatch/contact/.

- Categories: