At the Dawn of Flight

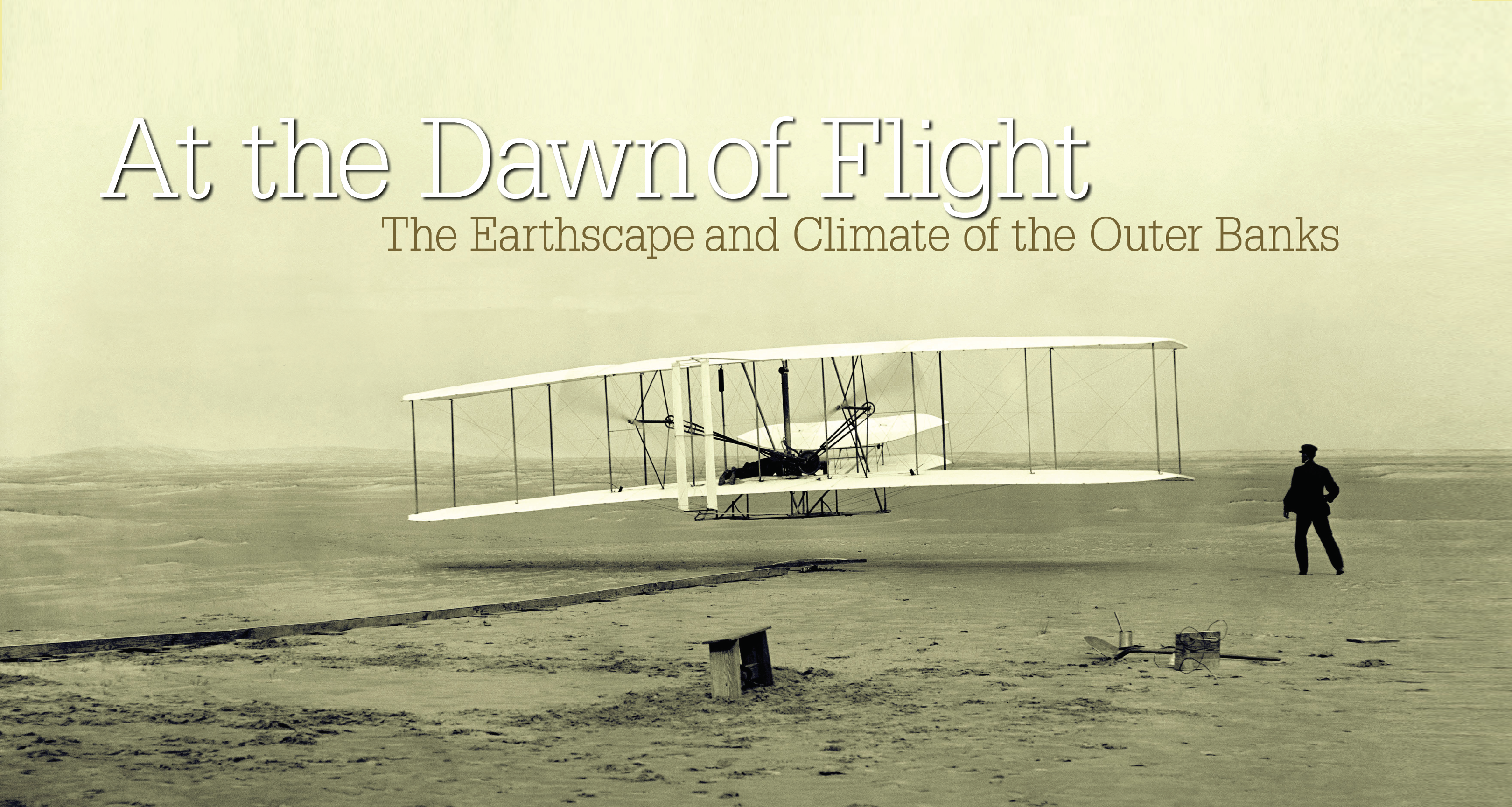

The first successful flight of the Wright Flyer. Photo courtesy of the Library of Congress.

BY LARRY E. TISE

Torrential winds, wild ponies, marauding pigs, and an ever-shifting coast — they all came with one of the best laboratories on the planet for learning how to fly.

“I chose Kitty Hawk because it seemed the place which most closely met the required conditions,” Wilbur Wright wrote his father, Bishop Milton Wright, on September 9, 1900. Inscribing his first letter from North Carolina on the stationery of the Hotel Arlington at Elizabeth City, the elder of the two Wright brothers who invented flight explained why the tiny fishing village on the Carolina coast provided the perfect place for conducting “practical experiments” on what he called “the flying question.”

“At Kitty Hawk, which is on the narrow bar separating the Sound from the Ocean,” he continued, “there are neither hills nor trees, so that it offers a safe place for practice.” Besides, “the wind there is stronger . . . and is almost constant” — sufficient, he believed, to lift from the ground a controlled, man-carrying flying machine.

What he called “the required conditions” at Kitty Hawk had been confirmed to him by both the world’s foremost authority on flight at the time — Octave Chanute — and the U.S. Weather Bureau. Those required elements included several crucial items: sustained winds in one direction of 21 miles per hour; soft sands for many inevitable crashes; remoteness from the prying eyes of big-city newspaper reporters; and reliable transportation access from Dayton, Ohio. No other place known to either Chanute or the Weather Bureau contained all those factors the Wrights sought as their most permanent laboratory for testing several modes of flight.

But neither Wilbur Wright nor his brother Orville had ever flown in an airship or a flying machine, nor even attempted to make any kind of device, other than a kite, that would fly. Nor had they ever seen an ocean — much less the kind of barren, sandy, windswept barrier chain of islands they were about to experience for the first time on the coast of North Carolina. Wilbur described Kitty Hawk as unduly remote — even to the people in Elizabeth City. “No one seemed to know anything about the place or how to get there,” Wilbur told his family.

Eventually, he got passage from Elizabeth City to the place with a local fisherman on a “flat-bottomed,” “half-rotted,” and “vermin-infested” boat that barely withstood, he thought, the high waves and surging currents of the treacherous waters between the mainland and Kitty Hawk Bay. He was certain that the skipper, one Israel Perry, was incompetent — that the man could neither command his shabby boat properly nor capably ply what Wilbur perceived as the stormy seas of the vast Albemarle Sound. Wilbur thought it almost a miracle that he had survived the dangerous voyage.

Finally arriving on the sliver of sandy and scruffy land between the normally calm Albemarle Sound and the surging waves and tides of the Atlantic Ocean, Wilbur and Orville Wright in 1900 began their experiments. Despite the distance from their orderly Ohio home, the unpredictable patterns of weather, swarming hordes of bloodsucking mosquitoes, roaming armies of hungry pigs, sand-filled shoes and blankets, chilling nor’easters, walloping hurricane-force winds from the south, and every other surprise of raw nature and guileless men, the brothers Wright forged ahead — still unsure about their testing grounds.

When he got across the Albemarle Sound to Kitty Hawk on September 11, Wilbur was welcomed as an out-of-state guest and as a temporary boarder at the home of William J. and Addie Tate. The Tates’ small clapboard and wooden-shingle house served doubly as their family residence with their young daughters Irene and Pauline and as the official U.S. Post Office for Kitty Hawk. Being able to perch for three weeks in a local home was a godsend for the young man from Ohio.

His hosts possessed the inherited ways in which coastal people for thousands of years had coped with their unusual world. It was an environment that was inviting when the weather was fair and hellish when winds and storms and ripping tides lashed across the narrow threads of sand.

During the day, Wilbur worked in the barren yard of the Tate house, cobbling together the first Wright flying machine. In the evenings he sat at supper with the family, hearing about the wild animals that lurked across the scraggly land and the ways humans withstood the persistent assaults of weather, sand, and biting insects. This initial encounter with the Tates would never be forgotten. The Tates remained lifelong friends and advocates of the Wrights and their pioneering flights on the Carolina coast for the remainder of their lives. Bill, in particular, later styled himself as an official guide to the Wright brothers’ Carolina coast and promoted in both North Carolina and Washington, D.C., the creation of a monument marking the most important site of America’s first powered flights.

When Orville arrived almost three weeks later, the brothers supped on duck and rabbit and fish — standard local fare in those parts — with the Tates and listened to more coastal lore until October 4, when they ventured on their own into nature. For the next 19 days, the brothers, inexperienced as campers, felt they had mounted a wild and unpredictable steed. They set up a tent on a sandy hill half a mile from the Tate home — roughly halfway between Kitty Hawk, a cluster of houses on the sound side of the banks, and the Kitty Hawk Life-Saving Station on the Atlantic shore side. To their consternation, their tent was blown down repeatedly by winds ranging from 30 to 45 miles per hour.

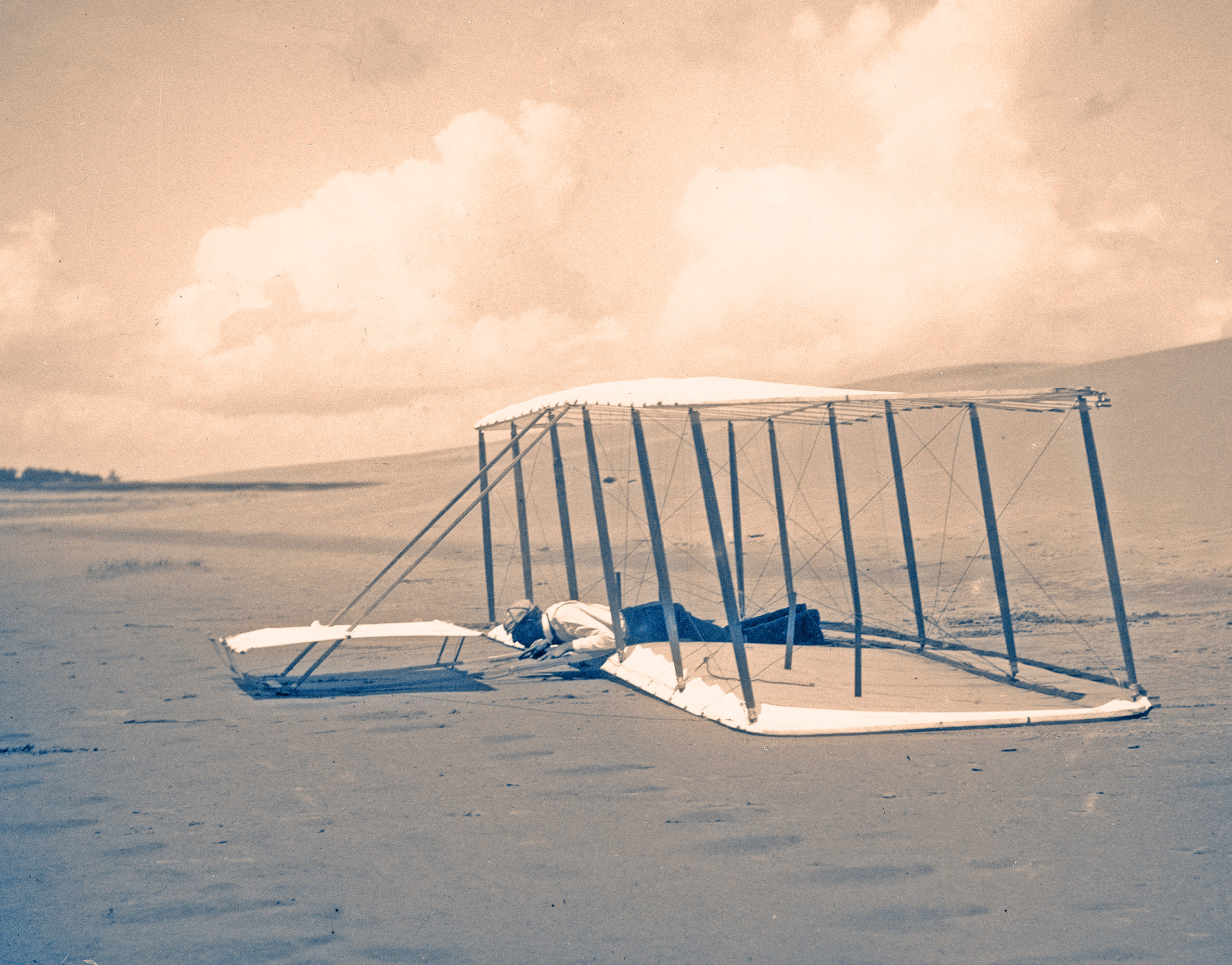

They took their first flying machine, a smallish device, out and tried to fly it as a kite. That worked well. They then tethered it by ropes to a wooden derrick they had built for testing the craft. But the flying machine was thrashed around and upended whenever they tried to work with it. Although Wilbur built the machine to carry five times his weight, it would not carry him aloft when it was flown as a glider. Adding insult to injury, the machine crashed and was left in a heap of broken rubble when crosswinds threw it into a dune known as “Look Out Hill,” which the brothers renamed the “Hill of the Wreck.”

But all was not lost. When the machine would not lift Wilbur’s 130 pounds, along came a small boy, Tom Tate (a nephew of Bill Tate). He was “a small chap [70 pounds]…that can tell more yarns than any kid of his size I ever saw,” said Orville. The crude flying machine rose with the diminutive Tate aboard without difficulties.

But when the smallish dunes at Kitty Hawk sometimes lacked the constant winds they sought, the brothers moved four miles southward to the much larger Kill Devil Hills. There, they found both perfect winds and an open terrain more suitable for flight. These large dunes — near no town, but adjacent to the Kill Devil Hills Life-Saving Station — became the locale for all the brothers’ tests in their subsequent trips to the Carolina coast across the next 11 years.

In addition to reckoning with the gusting and swooping winds, the brothers also began to understand the earthscape of the place where they hoped to fly. “But the sand!” exclaimed Orville. “The sand is the greatest thing in Kitty Hawk, and soon will be the only thing,” he prophesied. He and Wilbur could see the results of recent shifts in the sands in the landscape of rotted limbs — once belonging to proud trees — that protruded from the sand.

“The sea,” he observed, “has washed and the wind [has] blown millions and millions of loads of sand up in heaps along the coast, completely covering houses and forest.” One night a “45 mile nor’easter” struck their camp and “took up two or three wagon loads of sand from the N.E. end of our tent and piled it up eight inches deep on the flying machine we had anchored about fifty feet southwest.” While this was happening, the sides of their tent snapped repeatedly, sounding “exactly like thunder.”

While the Wright brothers marveled at the moving landscape of their test grounds, a young geology professor at the University of North Carolina in Chapel Hill, Collier Cobb, attempted to explain the ebb and flow of sands on the barrier island chain for the National Geographic Magazine in 1906. According to Cobb, the advancement of sands and the formation of great new dunes around 1900 was the result of years of people denuding the pine forests that had flourished on the Carolina banks for eons.

“This movement of the sand was started just after the Civil War by the cutting of trees next to the shore for ship timbers,” he wrote. He found that an entire fishing village on Hatteras Island had been buried by sand near a spot known as “The Great Woods” — where “not a stick of timber stands upon it today.” Cobb’s assessment of the changes was the best guess in an era that lacked essential data on the rise and fall of oceans that would be available to scientists a century later. (For the current science behind the state’s shifting coastline, see “A Brief History of Sea Level Rise in North Carolina” in the Winter 2019 issue of Coastwatch.)

Aside from the constantly shifting sands, one of the other fundamental modifications in the shape of the Carolina coast was the never-ending creation and melting away of inlets from, and thereby outlets to, the Atlantic Ocean across its barrier islands. The island chain experienced by the Wright brothers in 1900 looked nothing like the coast that had been encountered by the explorers sent to the same region by Sir Walter Raleigh 300 years earlier.

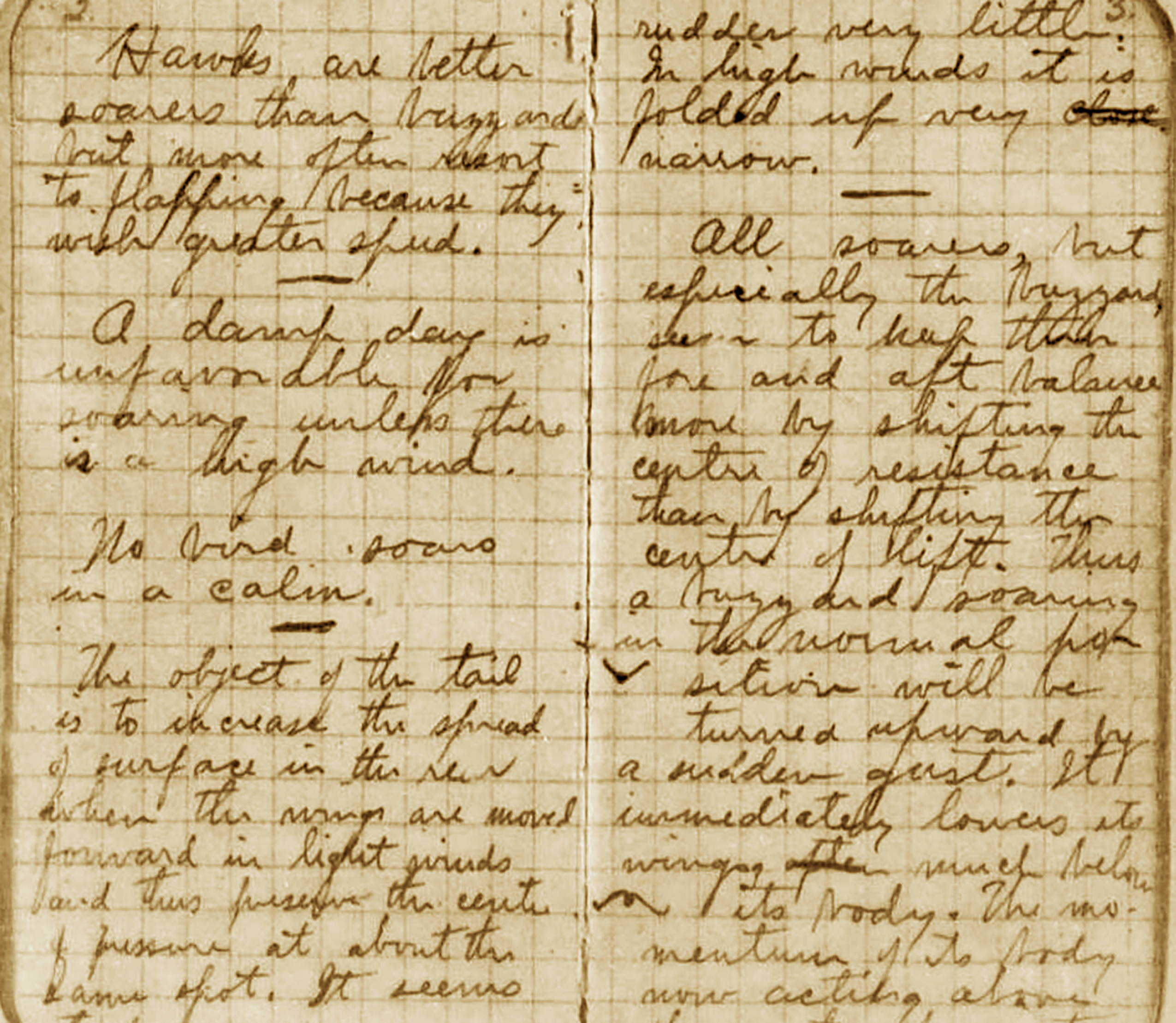

Whereas the Atlantic’s salty waters had spilled into the sounds through porous inlets twice daily with the rise and fall of every tide, the disappearance of these water channels transformed the upper banks region of North Carolina — the Albemarle Sound — into a gigantic freshwater sea. As one of the largest freshwater habitats in America, the Albemarle became a lush environment for the growth of wide spans of the grasses beloved by migrating fowl. In the process, this inland sea became a perfect laboratory where the Wright brothers could study the behavior of soaring and swooping birds in flight. The seasonal shifts of millions of duck, geese, and other migratory birds from Canadian to South American habitats made the inner side of the Carolina’s barrier islands one of the richest sites for the targeting of waterfowl in the Americas.

Another result of the closing of the inlets was a modification in the fish and shellfish culture of coastal Carolina. The transformation of the Albemarle Sound into a freshwater environment meant that its population of shad, herring, and striped bass exploded. Every February through April thereafter millions upon millions of these and other freshwater species could be harvested without depleting the abundance.

But the disappearance of salt water north of Roanoke Island also meant that these waters could no longer produce oysters. Indeed, when North Carolina in 1887 had commissioned a study of its coastal waters for the purpose of expanding the cultivation of oysters, its principal scientist excluded the entire Albemarle Sound region from its survey of existing oyster beds. But the presence of an abundant resource of fish and other sea life, ready to be harvested, was one of the defining characteristics of coastal Carolina at the turn of the 20th century.

While the opening and closing of inlets along the Carolina coast had a profound effect on the natural habitat of the region, by the first years of the 20th century the presence or absence of these natural openings between sound and sea had little effect on the lives and habits of coastal Carolinians.

As residents of one of the most constantly changing environments on the American coast, lifelong habitués of the region adapted to the changes. Sharing information on changing channels for boating and fishing, locals adjusted to the moving barrier islands, the relocation of fish and shell beds, and access to the Atlantic for saltwater fishing. There was no need in 1900 to build highways or bridges or to operate a fleet of ferries to convey vehicles from island to island. The daily experience of coastal residents was a water-based lifestyle and existence. Everyone proudly possessed a boat.

Although neither Wilbur nor Orville graduated from high school, they were quick learners who adapted rapidly to their newfound coastal environment. They became accustomed to seeing cattle and wild ponies roaming across some of the grassy expanses around Kitty Hawk. They expected to encounter from the outset the sudden appearance at their camp of marauding pigs perpetually rooting for edibles not yet consumed by human beings.

As the Wrights lofted their experimental flying machines into the complicated flux of air over Kitty Hawk, they also became experts in the acquisition and use of meteorological information. As keen observers of climate, they made daily calculations on wind, barometric pressure, and temperatures. They saw the mighty power of winds, storms, and furious seas that could move mountains of sand across the thin Carolina barrier islands. They saw trees that had been humbled by constant winds bowing away from the torrential blasts of air. They endured both hurricanes and tropical storms as they learned to turn nature on the continental fringe into an asset for inventing flight.

When storms were not brewing, they noted more pleasant spectacles of their ocean environment.

“The sunsets here are the prettiest I have ever seen,” observed Orville. “The clouds light up in all colors in the background, with deep blue clouds of various shapes fringed with gold before. The moon rises in much the same style, and lights up this pile of sand almost like day.”

Finding a kinship with his newly discovered natural workshop, Wilbur wrote his sister Katharine somewhat nostalgically as he and Orville left the coast for the first time in 1900: “We have said ‘Good bye Kitty, Good bye Hawk, good bye Kitty Hawk, we’re gwine to leave you now.’”

With what they had learned about this fragile but volatile coast, about the people who lived there, and, most importantly, about themselves, they would be able to return for years, better prepared to take advantage of one of the best places on Earth for flying.

From Circa 1903: North Carolina’s Outer Banks at the Dawn of Flight by Larry E. Tise. Copyright © 2019 by the University of North Carolina Press. Used by permission of the publisher. UNCPress.org

Order Circa 1903: North Carolina’s Outer Banks at the Dawn of Flight here.

from the Spring 2020 issue of Coastwatch

- Categories: