Beauty in the Eye of the Beholder: Hammocks Beach State Park

PROLOGUE

There are many stories to tell, and many ways to tell them. A story about a person, for example, is straightforward, sometimes biographical. A story about an event must be factual, perhaps based on historic evidence.

The story of a place — especially if that place is Hammocks Beach State Park — is often much more subjective. Its telling is colored by the perspective and experience of each storyteller.

Some elements, of course, are universal. Hammocks Beach State Park is located near Swansboro in Onslow County. The park’s 33-acre, wel-lappointed mainland site is a boat ride away from the main attraction — Bear Island, an 892-acre, undeveloped barrier island. The biodiversity of the newly acquired Huggins Island is well-documented. The 110-acre island of uplands, swamp and inland marshes could become an education and research jewel.

Common, one-word descriptors for the park complex might include “remote,” “tranquil” or even “primitive.”

CHAPTER ONE: The Vision

Park Superintendent Sam Eland’s story of Hammocks Beach is best told from atop a high dune on Bear Island. A picture-perfect sunrise illuminates the park’s watery boundaries and diverse environmental assets.

The complex is embraced by Queens Creek, the White Oak River, the Intracoastal Waterway, the great Atlantic Ocean — and restless inlets, acres of pristine tidal marsh and estuarine waters, and miles of oceanfront beaches.

The purchase of nearby Huggins Island in 1999 bought protection for the environmental integrity of Hammocks Beach State Park, Bland explains. The lack of development eliminates the threat of leaching septic systems or stormwater runoff from hardened surfaces — effects that could degrade surrounding waters and the diverse ecology of the island itself.

Partnerships were the key to the island’s acquisition and inclusion into the park system. Funding came from the N.C. Clean Water Management Trust Fund, the N.C. Natural Heritage Trust Fund and the N.C. Division of Parks and Recreation. Additional support was from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, the N.C. Wetland Restoration Program and the North Carolina Coastal Federation.

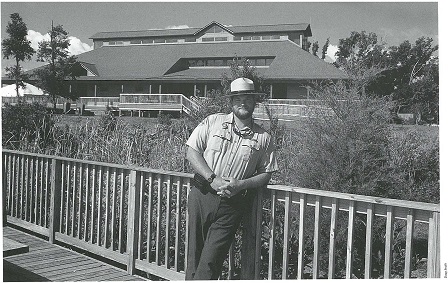

The view across the marsh toward the mainland visitors’ center, ferry dock and boat launch areas provides a glimpse of the park’s recent history as well as Bland’s vision. When Bland was transferred to the park some 15 years ago, the mainland area was little more than a one-acre jumping-off place for the ferry and private boats heading for Bear Island. Since then, the state’s acquisition of additional acres provided the catalyst for needed facilities expansion.

The recent completion of a handsome visitors’ center is one step toward making Hammocks Beach State Park a year-round destination for people interested in learning about the coastal environment, Bland says. Soon-to-be-installed exhibits will reflect the natural features of the coastal area from the marsh to the beach — and all the ecological zones of Bear Island and Huggins Island.

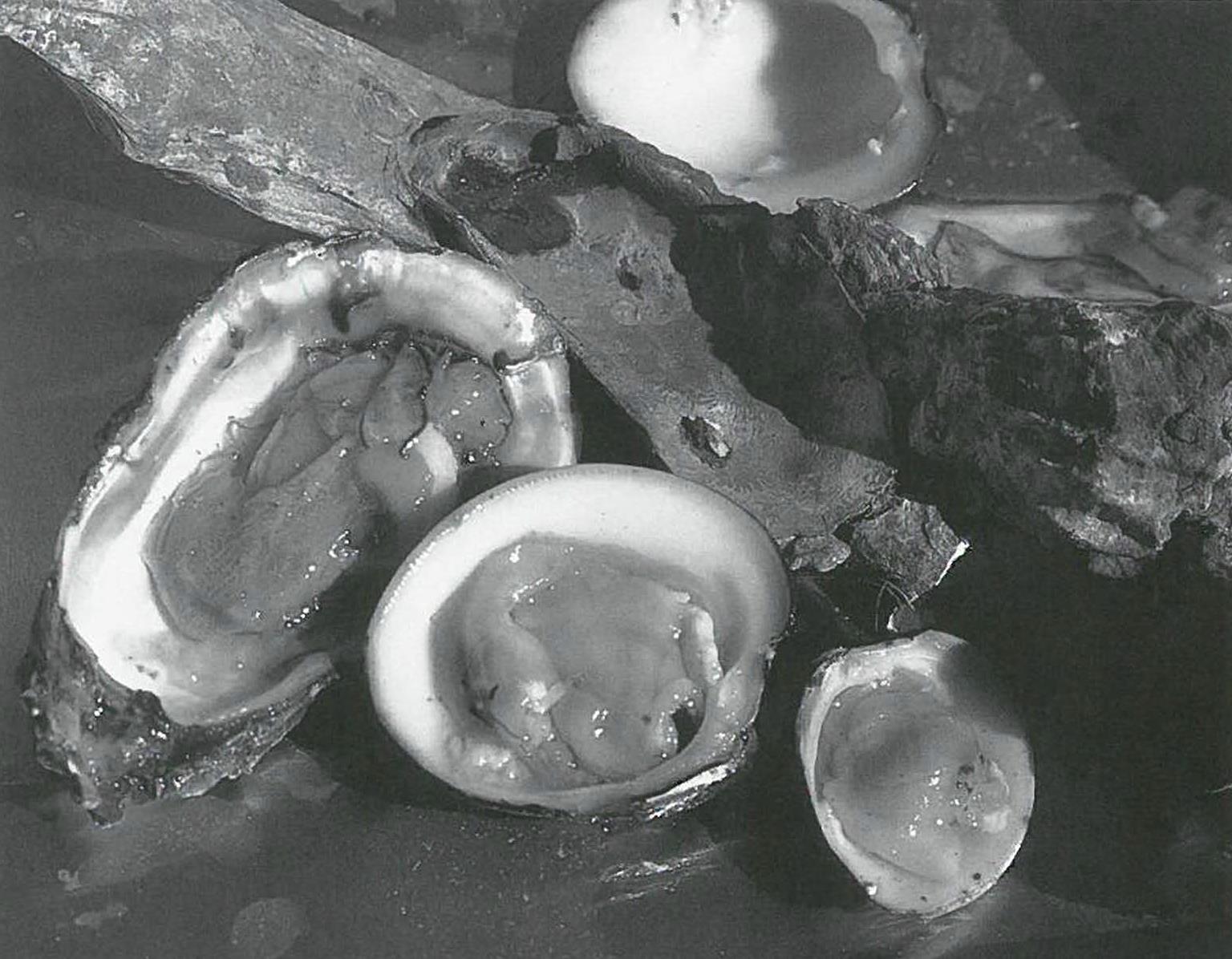

Park rangers have participated in the federal loggerhead sea turtle protection program since 1975. They began tagging nesting turtles a decade ago. “Many turtles return to Bear Island beaches over and over to lay their eggs,” Bland says.

The island also is ideal for the study of colonial nesting birds. In addition, the state’s Natural Heritage Program conducted a baseline survey of flora and a cultural history of park properties. Park staff members add to the “inventory” with newly discovered natural treasures.

A mini-theater will feature videos of the nesting sea turtles, coastal birds, Bear Island’s remarkable dune system — and the night sky that captivates campers.

“These are things that people come to see and enjoy. The message will be one that advocates conservancy and stewardship on both a local and global scale,” Bland says.

“Visitorship is huge,” Bland says, “But ours are not your average tourists. Our visitors are environmental advocates who appreciate primitive camping and the rare qualities of an undeveloped barrier island.”

In contrast, just across Bogue Inlet, lies Emerald Isle — a barrier island with side-by-side houses, condos and commercial properties from ocean dunes to the edge of the sound.

Thanks to the protected status of the complex, that will never be a scenario in Eland’s park story.

CHAPTER TWO: The Partners

Todd Miller, executive director of the North Carolina Coastal Federation, is likely to begin his story with a bit of history.

In the 1920s a wealthy New York surgeon owned the island and a 4,600-acre mainland site known as “the hammocks.” He intended to will Bear Island to the family of his long-time hunting and fishing guide, John Hurst. But Hurst suggested that he donate it to the North Carolina Teachers Association, an organization of African-American teachers.

The island was under the association’s management for more than a decade. In 1961, the association donated the undeveloped island to still-segregated North Carolina for a park for minorities. It opened as Hammocks Beach State Park for all citizens following the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

Miller’s story also is flavored by his memories of growing up in Ocean, a nearby community. Here is a setting that lends itself to idyllic summer days exploring a maritime forest, spotting blue crabs in a tidal marsh, and jumping waves on a perfect beach.

Hammocks Beach State Park remains a stellar facility, he says. “Its management is a model of stewardship.”

That’s a high compliment from Miller, whose love for coastal North Carolina is both a vocation and an avocation. He founded the Coastal Federation in 1982 as a rallying point for people who feel deeply about the coast and want to help preserve priceless ecosystems.

“Our role is to prod the political system and keep things moving,” Miller says.

It’s also one of action. Not surprisingly, Miller and the federation are staunch park supporters and partners. Along with helping with the Huggins Island purchase, his organization helped to plan the expansion of the mainland areas. The imperative was to maintain or improve water quality.

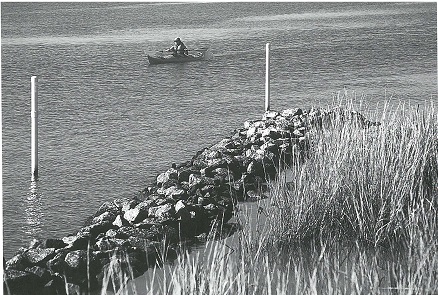

Talk about timing. Park officials were ready to remove an old bulkhead at the original mainland ferry dock. Tracy Skrabal, federation senior scientist, was looking for a laboratory for estuarine shoreline erosion control.

“It was an opportunity to do things differently,” says Skrabal. The first phase was to remove the bulkhead and replace it with natural vegetation to filter and absorb runoff from the impervious parking lot.

Skrabal says the creation or restoration of natural marshes is a cost-effective way to buffer boat wakes, reduce pollutants entering the water, enhance fisheries and near-shore habitat, and improve the aesthetic view from land and water.

Skrabal says the efforts address immediate water quality concerns and the possibility of chemicals leaching from treated wood. The plan also eliminates costly repairs to aging wooden bulkheads.

In addition, Skrabal designed a constructed wetland to meet stormwater management needs at the new visitors’ center and ferry dock.

The Coastal Federation also is leading an effort to have the White Oak River designated as a “Recreation and Scenic River” by the federal government. This will provide additional protection for the pristine waters just behind Bear Island.

To strengthen the cause, the federation joined forces with the U.S. Forest Service and local citizen groups, the Carteret Canoe and Kayak Club and Crossroads.

“In North Carolina, so many people are directly affected by so many aspects of the coast. Those are the people who can energize an issue to get something done — or at least can get the ball rolling to raise awareness to what is important,” Miller says.

“One person starts the ball rolling, and others add shoulder or clout — whatever it takes to maintain the momentum.”

CHAPTER THREE: The Experience

Soon, new voices will be telling their own stories based on experiences at the Coastal Federation Summit held at Hammocks Beach State Park. The summit is a time to reflect on accomplishments and to become energized to meet the challenges ahead.

The entire park is a classroom, where conference participants become students and spread out for crash courses in coastal processes, history and culture. Their newly discovered “facts of life” will be incorporated in their telling — or will frame a deeper understanding of future news articles or political debate about coastal issues.

Bland Simpson, author of Into the Sound Country, spins modem folklore in the context of the coastal history and culture. He tells of people whose roots sink deep in sand, streams and salty marsh; of watermen who know where fish are running; and of isolated coastal communities where people may be poor, but not in need.

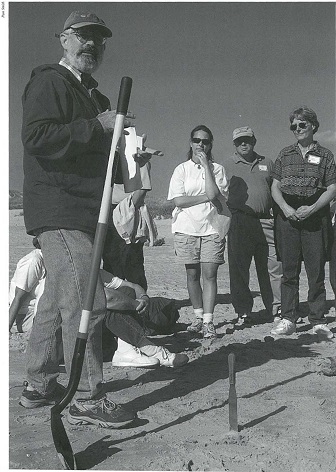

And, on the sandy beach of Bear Island, Richard Spruill, an East Carolina University hydrology professor, provides insight into a hidden resource on this unspoiled island — fresh water. He explains the water cycle, relationships between groundwater and surface waters, stormwater runoff and the water supply.

The bottom line? The freshwater aquifers that provide drinking water to coastal communities are under great pressure from the population boom of the past decade. There is not an infinite supply of fresh water.

Nor is there an infinite amount of sand in the coastal beach system, says John Wells, professor of geology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. The beach is his blackboard, a spatula his chalk as he illustrates long-shore transport of sand.

Wells believes there are three truths of science. Nothing is black or white. Science is not isolated, but rather integrated with economics and politics. Science evolves.

Some members climb into canoes and kayaks to quietly paddle through creeks, marshes and sounds surrounding Bear Island. They may catch a glimpse of osprey and skimmers, cormorants, great blue herons and laughing gulls. If they’re lucky, they may see a playful otter or curious dolphin. They’ll also learn how marsh grass filters pollutants.

Ranger Kevin Bleck maneuvers the ferry as close to the Huggins Island shore as he dares at low tide. He wants to offer passengers the best view of the park’s new jewel. He tells them the state has given an Outstanding Resource Waters designation to much of the surrounding waters.

The island holds clues to its place in coastal history from Native American artifacts to an earthen Civil War fort to remnants of a peach orchard.

Park officials are studying how to provide access to the island for education and research while protecting its ecological qualities — including a rare freshwater swamp.

Bleck, a native of Maine, says he was drawn to Hammocks Beach State Park by its natural beauty. Each day is a new story. “It may be a dramatic view of a nesting pair of eagles on one of the islands in the marsh. Or the dolphins — every time I see them, it’s special,” he tells the passengers.

As far as coastal federation volunteer Harry Wigmire is concerned, the day in the park is a huge success. “It opens up the coast for a lot of people. It’s hard to measure its educational value, but I met a lady from Ohio who never saw a blue crab until today. Today made a difference for her.”

They all will have stories to tell, he says.

DENOUEMENT

Sunset may lure Superintendent Bland back to Bear Island to conclude his well-told tale. The magenta sky reflects across the marsh.

“I want to let people know and understand that the marsh is more than an aesthetic view. It’s a productive ecosystem. It’s a nursery for most commercial and recreational fish North Carolina anglers enjoy.”

But the beauty doesn’t escape the superintendent. His favorite time and place?

“Sunset in the dunes on Bear Island — especially when the fading light catches the blue stem that bloom in the fall of the year.”

This article was published in the Winter 2002 issue of Coastwatch.

For contact information and reprint requests, visit ncseagrant.ncsu.edu/coastwatch/contact/.

- Categories: