Cynthia Sharpe is a communications intern with North Carolina Sea Grant. She is a senior majoring in English at North Carolina State University.

North Carolina’s coastal region is not just a destination for fishing, bird watching and enjoying sunny beaches. It is a region of history. Eastern North Carolina has many sites that reflect the richness of African-American life over the years, and places that always deserve attention, not just during February’s celebrations of black history.

These locations reflect the ups, the downs, the work and the culture of African-American communities during and after slavery. This summer, pack a few lunches, gather the family and hop in the vehicle for an adventure that will take you to some beautiful places, and leave you more knowledgeable about African-American heritage in coastal North Carolina.

SWAMP AS SANCTUARY

Begin the journey at the top of the state. The Great Dismal Swamp, shared by Gates, Pasquotank and Camden counties, stretches into Virginia. The N.C. Division of Parks and Recreation manages a portion of the swamp as a state park, while the majority is a National Wildlife Refuge, under the jurisdiction of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

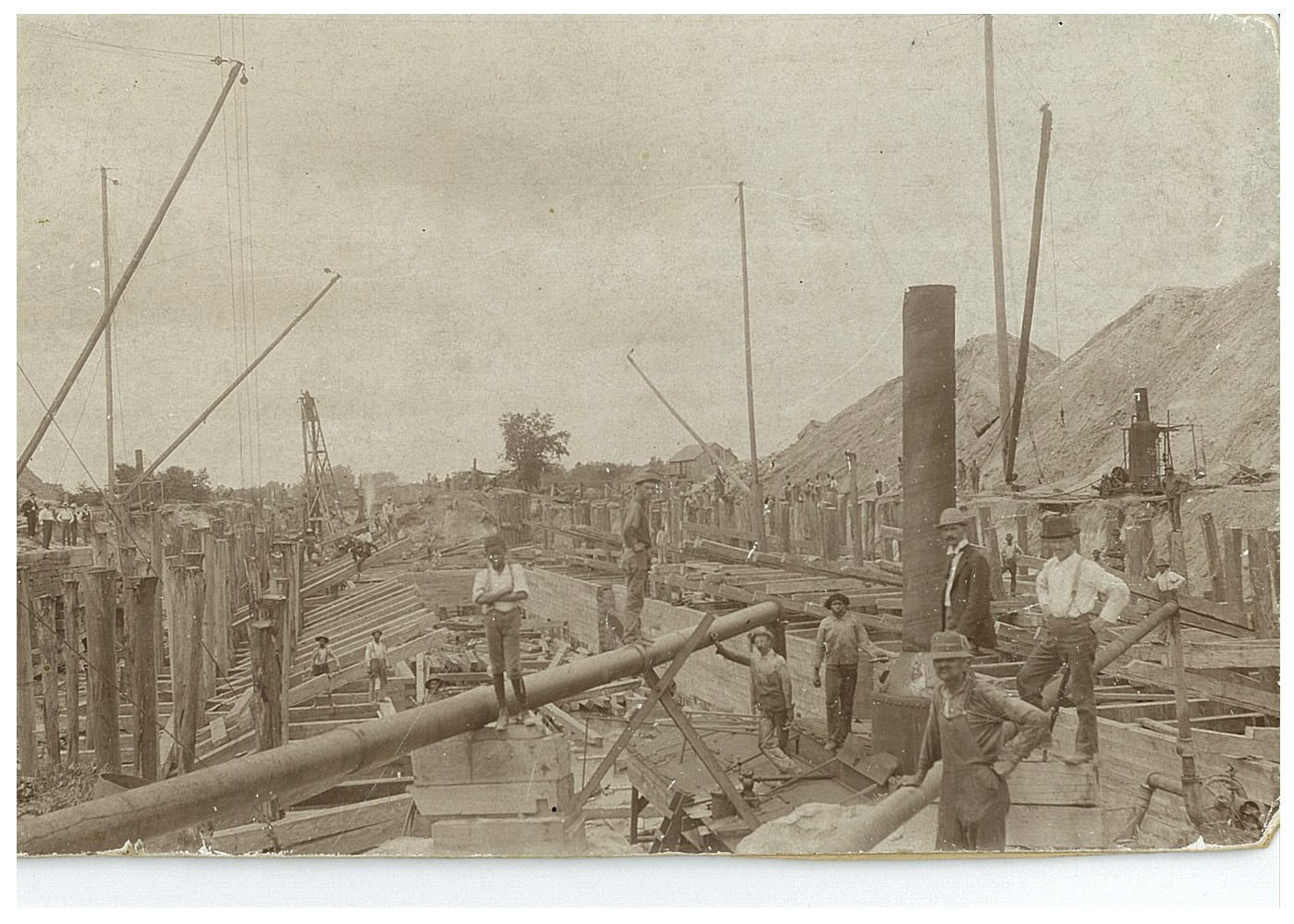

In the Dismal Swamp State Park, bike or hike more than 20 miles of trails — including 2,000 feet of boardwalk — that wind through the swamp, or paddle on the Dismal Swamp Canal. Opened in 1805, the 22-mile canal was dug almost entirely by enslaved people over the course of 12 years. Now part of the Atlantic Intracoastal Waterway, it connects Chesapeake, Va., to South Mills, N.C.

George Washington called it “a glorious paradise.” But for the runaway slaves that sought refuge there, life was difficult. The swamp was part of a maritime section of the Underground Railroad that existed in tidewater North Carolina between 1800 and the Civil War. The insects, snakes and treacherous landscape that inspired its name, made it a haven for fugitive slaves seeking their freedom.

The region also has a strong literary history. In his poem, “The Slave in the Dismal Swamp,” Henry Wadsworth Longfellow described the frightening environment and the terror of those who trekked through the area:

“In dark fens of the Dismal Swamp

The hunted Negro lay;

He saw the fire of the midnight camp,

And heard at times a horse’s tramp

And a bloodhound’s distant bay…

…Where hardly a human foot could pass,

Or a human heart would dare,

On the quaking turf of the green morass

He crouched in the rank and tangled grass,

Like a wild beast in his lair.”

In Narrative of the Life of Moses Grandy, the eponymous author and Camden County native describes his life as a slave working on boats that ply the Dismal Swamp Canal.

State park rangers regularly hold educational and interpretive programs. Signs and exhibits help visitors learn more about the history of the swamp.

“If you stop and listen closely,” says Donna Stewart, Dismal Swamp Canal Welcome Center director, “along with the rustle of the squirrels in the brush or the song of the warbler in the trees, you may hear the whispered secrets of those who sought refuge within her vine-covered walls.”

This summer, walk where fugitives ran, appreciate what slaves toiled to build, and reflect on the complicated greatness of the Great Dismal Swamp. It is a beautiful, peaceful, history-filled place.

For more information, go to www.ncparks.gov/dismal-swamp-state-park.

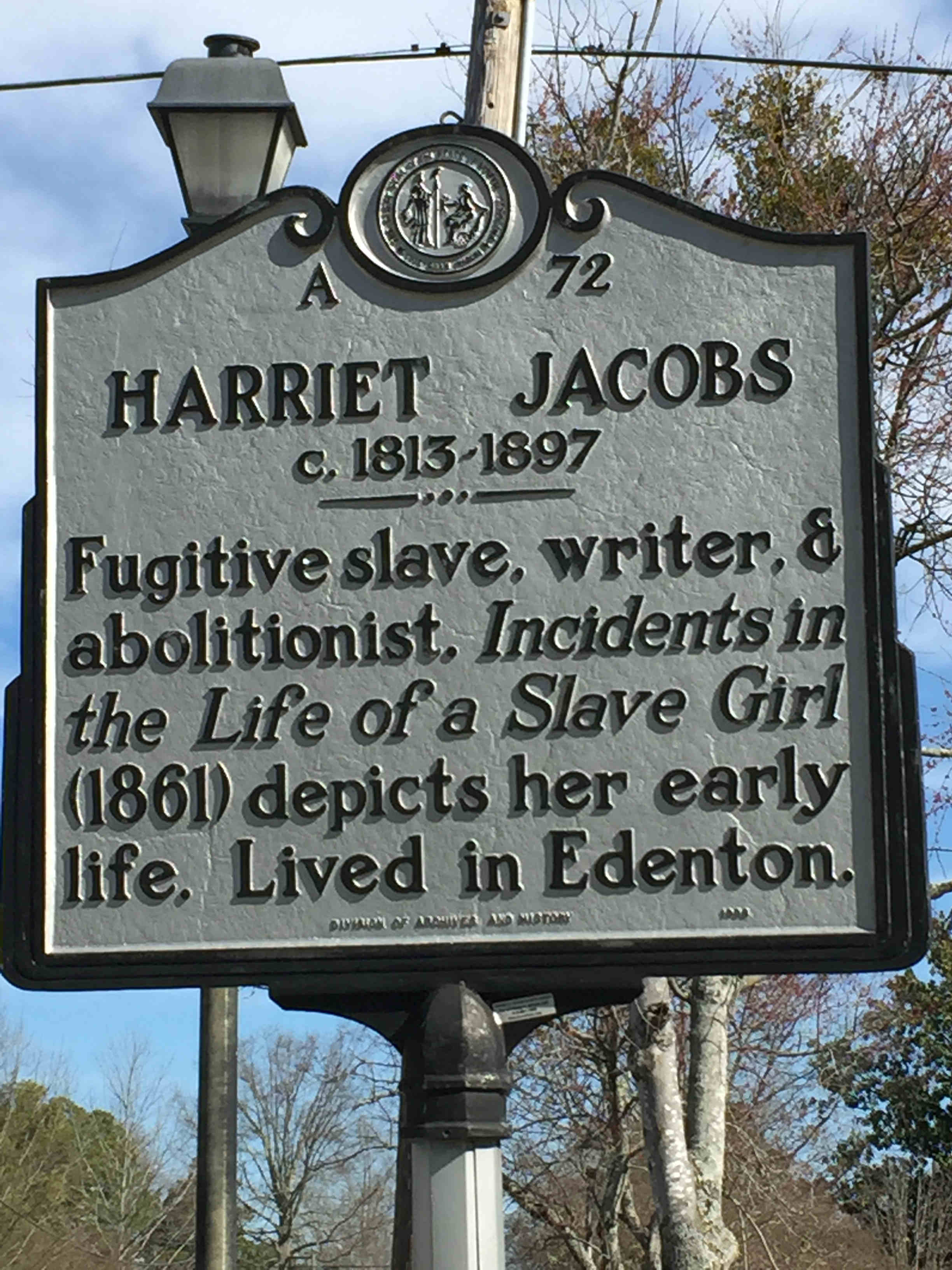

Harriet Jacobs’ Journey

Published in 1861, forgotten, then rediscovered during the Civil Rights Movement, Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl is the story of Harriet Ann Jacobs. Raised in Edenton as a slave, Jacobs eventually escaped her harassing master by hiding in an attic for nearly seven years then escaping to New York by sea.

Originally published under a pseudonym, the book is now credited to Jacobs. Her story is popular in classrooms and is commemorated in the community of her birth with the Harriet Jacobs Trail.

Born in 1813 to Elijah and Delilah Jacobs, Harriet Jacobs did not know until “six years of happy childhood” that she was a slave. In adolescence, she was tormented by the father of one of her owners.

By 1833, she had given birth to a daughter and a son. In an effort to leave her harsh master and one day free her children, Jacobs escaped in 1835. She stayed with neighbors at first, but eventually moved into the attic over a storeroom in her grandmother’s house. In 1842, Jacobs escaped to freedom.

“The Harriet Jacobs Trail is one of the few stories of an enslaved person seeking freedom via the Maritime Underground Railroad in this region,” says Charles Boyette, an interpreter for Historic Edenton State Historic Site. “Also, it is one of the best-documented accounts of what slavery was like for enslaved women told from their viewpoint. Together, this makes the Harriet Jacobs Trail a must-see site for anyone interested in African-American history, the Underground Railroad and women’s history.”

Various sites in Edenton reflect not only the life of Harriet Jacobs, but also the time period of the Civil War and places she described. The Historic Edenton State Historic Site Visitor Center at 108 North Broad Street has an exhibit about Jacobs, with photos and illustrations of people and places associated with her life. The center also houses her trophy from North Carolina Literary Hall of Fame, which she never got a chance to receive during her lifetime.

Guided Harriet Jacobs Walking Tours are offered February through March, Tuesday through Saturday upon request. Student tours are offered year round to eighth graders by reservation. For everyone else, a brochure focusing on Harriet Jacob’s years in Edenton can lead visitors on a self-guided walking tour.

To learn more about the Harriet Jacobs Trail, visit www.harrietjacobs.org.

Small-Town Significance

A little farther south on the North Carolina coast, off of U.S. 70, is James City. Similar to other small towns in the region, fast-food joints and small businesses line a main road. The land is flat with an abundance of trees, nothing too extravagant — until you consider its rich history.

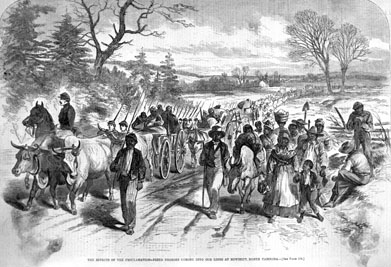

On the outskirts of New Bern in Craven County, James City used to be a place largely populated by freed blacks. After New Bern was captured in 1862 by Union troops, former slaves, with nowhere else to go, flooded the town. Eventually New Bern became the largest refuge for blacks in North Carolina.

Union Army officials provided confiscated land for the former slaves. Here, men and women established homes, churches, businesses and farms, and attempted to form an independent community. First known as the Trent River Settlement, by 1865 the population reached almost 3,000 and the community was renamed James City, after founder Horace James.

Near the end of the 1860s, harsh weather damaged crops. In 1867, the federal government returned the land to its original owners. By the 1880s, the black population dropped dramatically. Many of those who stayed not only had to pay rent, but made little profit from harvesting land that once had been theirs.

These circumstances did not stop James City residents from fighting for their place however. With the help of the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church, the people were supported financially. Labor unions formed and strikes occurred. But in 1892, after the Supreme Court of North Carolina ruled against the residents seeking that landowners pay for grievances, much of the black community dispersed. Only about 700 black men and women stayed.

Today, the church that attempted to save the city, now named St. Peter’s African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church, helps to preserve the history of the city along with The James City Historical Society. It is the first AME Zion Church in the state, built in 1864 and rebuilt between 1923 and 1940 after being burned in 1922. The church’s founder, James Walker Hood, went on to establish more than 350 other churches along the U.S. East Coast. St. Peter’s AME Zion Church still sits at 617 Queen Street in New Bern, and remains a pillar in the black community.

To learn more about the history of James City, visit the state’s Regional History Museum at Tryon Palace, North Carolina’s first permanent state capitol and now a history center. Information about tickets and tours can be found at www.tryonpalace.org.

Harboring History

A southern stop is in Wilmington — popular for its port, beaches, perfect movie locations and university. It also is known for its prominent role in slavery.

“Wilmington, North Carolina is among the most historically significant African-American regions in the United States. African-American ancestry is traced back to the 1700’s, and although much important history left no visible landmark, several historical sites still exist,” says Connie Nelson, communications/public relations director at the Wilmington and Beaches Convention & Visitors Bureau.

Due to the geography of North Carolina, slave ships could not reach the parts of the state blocked by the Outer Banks. Because of this, ships would head to the Wilmington port instead.

The port also is associated with the Maritime Underground Railroad. Slaves like Peter, a local pilot and engineer mentioned in David Cecelski’s book, The Waterman’s Song, were vital to helping slaves escape regularly. “But Peter navigated more than freight through those treacherous passages. He also steered fugitive slaves toward freedom along maritime escape routes that endured throughout the slavery era,” Cecelski writes in his study on slavery in the maritime South.

Wilmington also is known for its history of racial tension that came to a peak in the Wilmington Race Riot of 1898. After an election in which ballot boxes were stuffed by Democrats in favor of white supremacy, violence broke out in the city. Many African Americans were killed and hundreds were banished from the city. This ordeal resulted in more restrictions on African-American voters. The 1898 Monument and Memorial Park at 1018 N. Third St. honors lives lost during the riot and the progress made since then.

There are many opportunities in Wilmington to get a feel for the area’s history. Visit Bellamy Mansion Museum of History and Design Arts, built by free and enslaved African Americans. There are restored slave quarters behind the house.

In May, the Cape Fear Museum will open an exhibit, Reflections in Black and White. It will feature black-and-white photographs taken by black and white residents of Wilmington after World War II. Find more about ongoing and upcoming events at the museum that commemorate black life in the area at www.capefearmuseum.com.

American Heritage Tours, Inc., offers tours that take you to African-American sites and Historic Wilmington. You also can find other African-American heritage sites within the Wilmington/Cape Fear Coast area. To learn about these opportunities and more, go here.

The Bellamy Mansion and the City of Wilmington collaborated on A Guide to Wilmington’s African American Heritage. The publication highlights 37 historic, religious, educational, social and cultural sites that are or were important to African Americans in the city.

To find other locations to learn about African-American history in North Carolina, go to VisitNC.org and use the search function.

This article was published in the Spring 2015 issue of Coastwatch.

For contact information and reprint requests, visit ncseagrant.ncsu.edu/coastwatch/contact/.

- Categories: