The Great Deluge: A Chronicle of the Aftermath of Hurricane Floyd

This fall marks the 20th anniversary of Hurricane Floyd.

We look back at the infamous night the water rose and the days that followed — as survivors originally told the story in 1999.

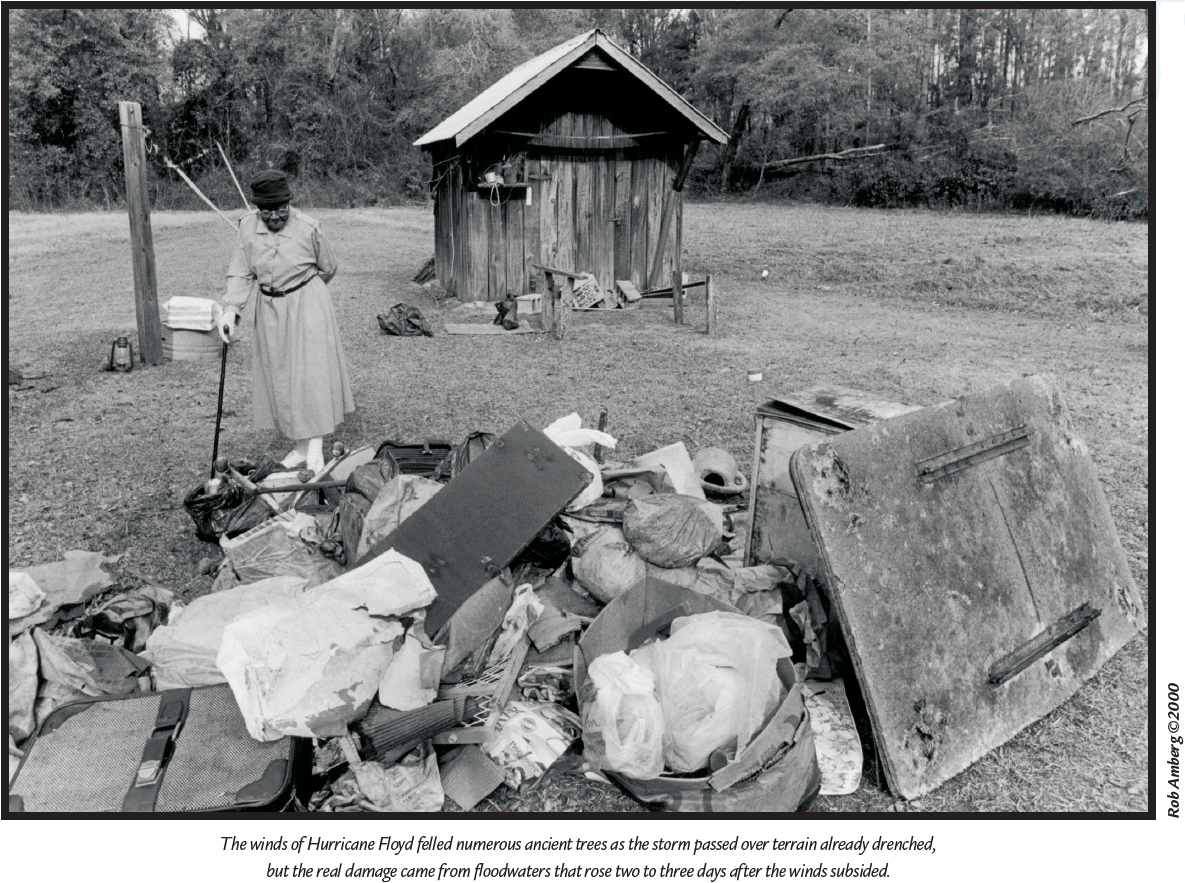

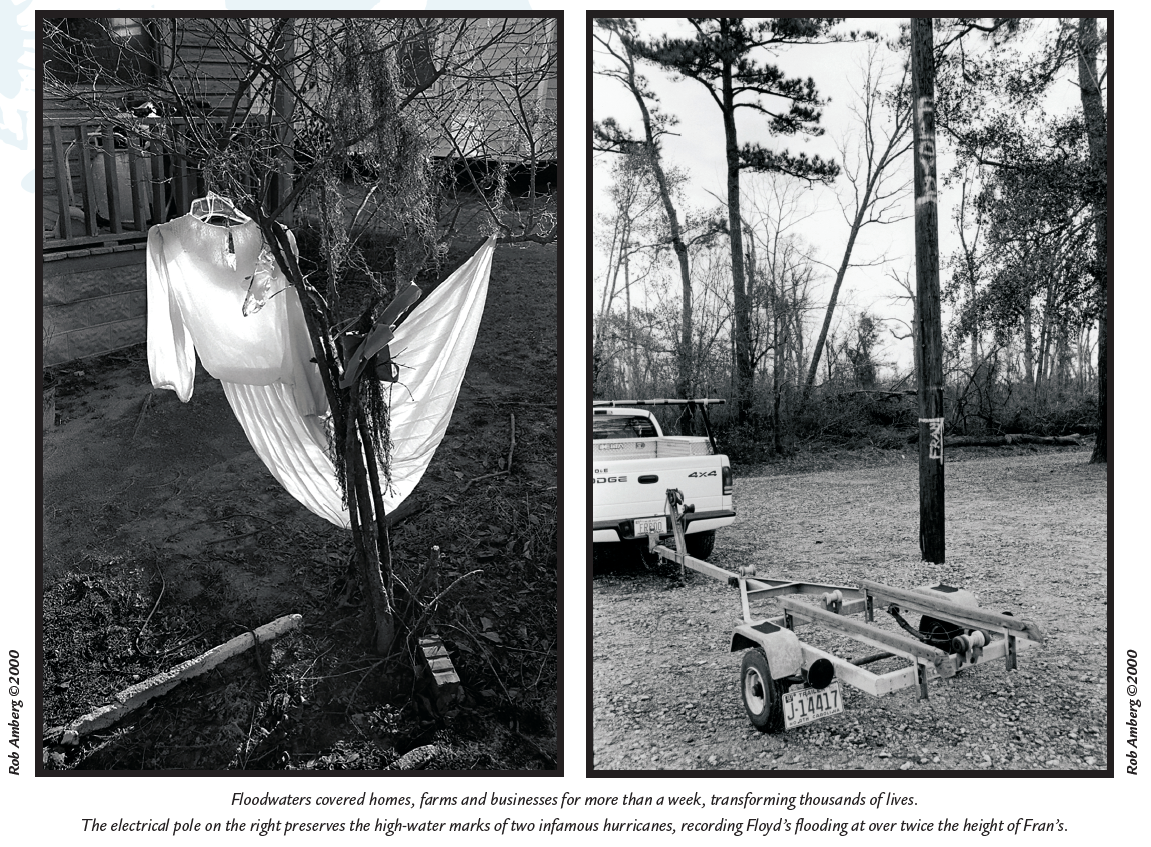

In the last 20 years, flooding from hurricanes Floyd, Matthew and Florence — as well as other tropical systems — has devastated North Carolina. When the first of these storms, Floyd, made landfall on September 16, 1999, at that time it was North Carolina’s worst natural disaster.

Floyd left 52 North Carolinians dead, a half-million without power, and 48,000 in shelters. Rising waters forced police and the military to perform 1,500 home evacuations. The storm flooded out 24 wastewater treatment plants and destroyed seven dams. Millions of livestock perished. Damage totaled several billion dollars statewide, including well over $500 million in lost crops, and 66 counties were declared disaster areas.

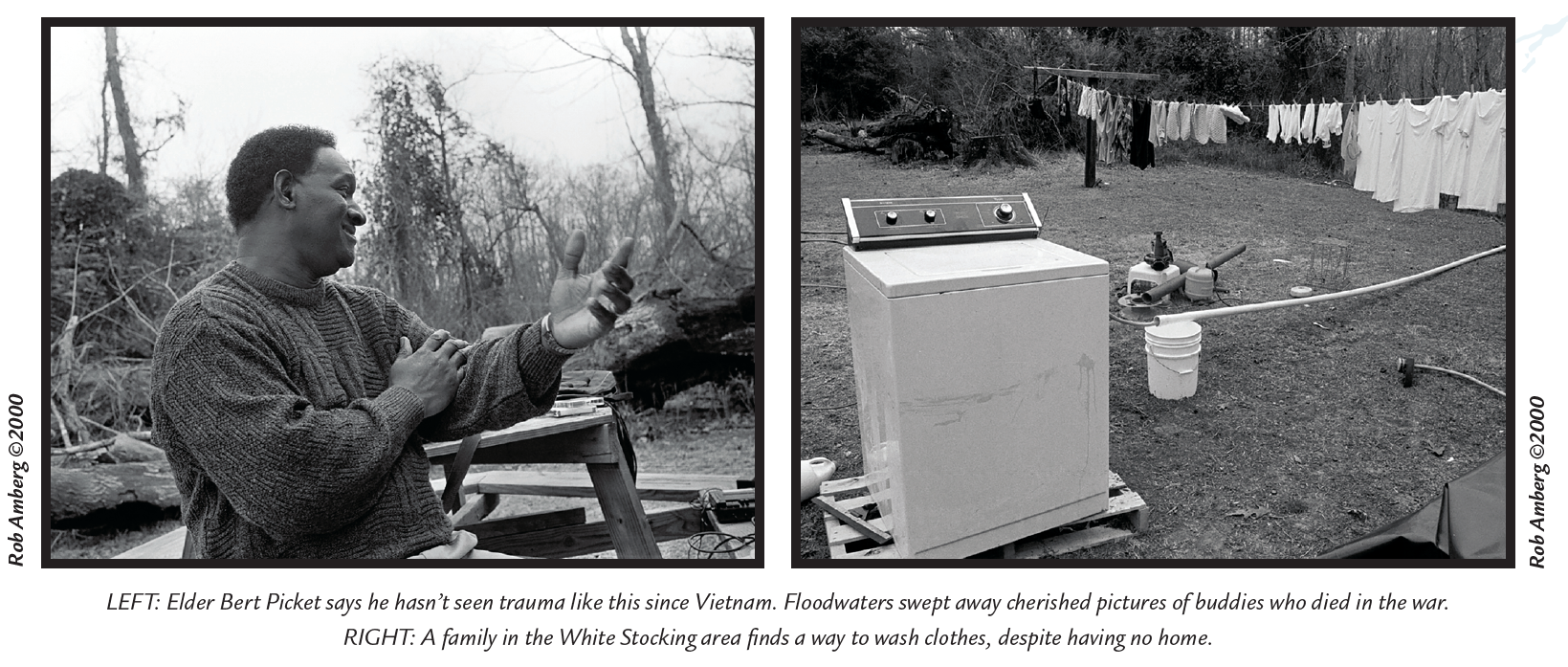

The swelling of the Cape Fear, Neuse and surrounding river basins transformed the geography and terrain of much of North Carolina. It also changed forever the people who endured it and left behind innumerable stories. Three months after Floyd, historian Charles D. Thompson Jr. and photographer Rob Amberg visited flood-damaged North Carolina communities to record eyewitness interviews about the hurricane and its aftermath. Survivors in communities like Tick Bite, Northeast, White Stocking and Grifton recounted Floyd and the long days that followed it. This is their chronicle of The Great Deluge.

“I walked out to the corner and walked over to where the bridge was at and just looked at the water to see how it was coming along. I’m saying to myself, ‘It’s not doing anything; we’re going to be alright.’ So I came back and went to bed.”

— Walter Davis Jr., Administrator at the Caswell Center, Grifton, North Carolina

“And the water was just trickling across the road. And I said, ‘Well, it’s about to peak out. This don’t come this high.’ And we came on home and went to bed.”

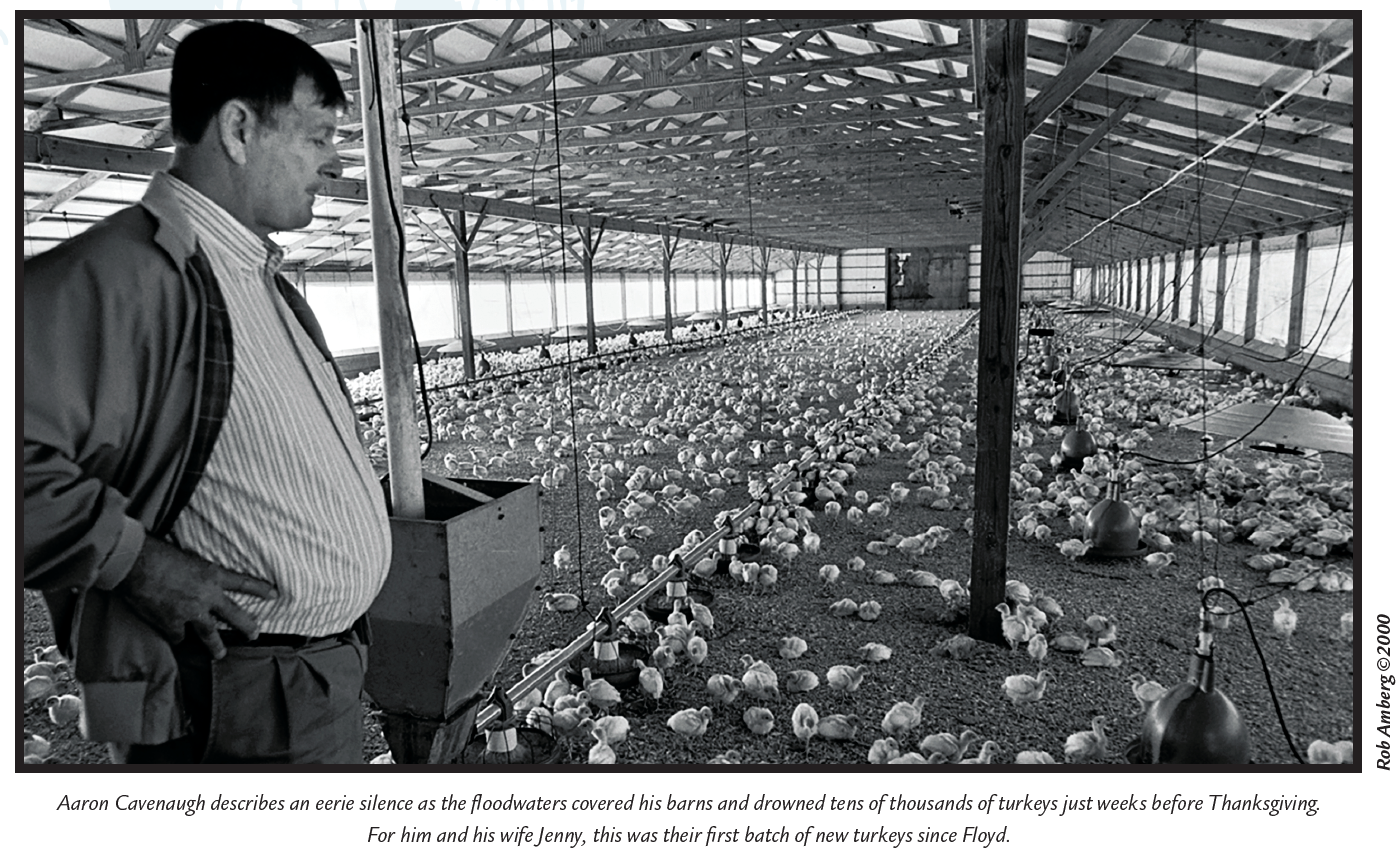

— Aaron Cavenaugh, Turkey Farmer, Northeast, North Carolina

“We’re blessed because when that flood came through here, I tell you what, it was just as pretty as it could be that Thursday. Sun was shining and it was warm… That night we went to bed, the lights were off… About the time we got to bed good, there were lights flashing to the window and the water was up just that quick. We hurried up and got our clothes on and got out and stepped in the water, right there to the doorstep. Just that quick.”

— Walter Davis Sr., Retired Dupont Employee, Grifton, North Carolina

“I didn’t know what was going on, so I got my flashlight. I walked out to see what was going on. I stepped out on the back porch, and water came up to… to my knees. And that woke me up. I got in high gear. And I already had an overnight bag packed… I just grabbed it, threw it in my truck and got out. Got out. It was something. It was unbelievable. I just did not realize how quick that water had rose like that.”

— Walter Davis Jr., Administrator at the Caswell Center, Grifton, North Carolina

“We were putting deeds and files in a trash bag and tying them up.”

— Jenny Cavenaugh, Turkey Farmer and Antique Dealer, Northeast, North Carolina

“The water was coming. I don’t know what kind of force it was, but it was terrible. The water was just rolling like there was pressure behind it. I just haven’t ever seen water do like that before. I was thinking that after we had gotten out — I said to myself, ‘The force that was behind that water; it might just wash the house down.’”

— Walter Davis Sr., Retired Dupont Employee, Grifton, North Carolina

“I felt like that I was a refugee or something because we were all — I mean I went out with my gown, a shoe of one color on each foot, and my pocketbook. That’s all… It came quick… You’re talking about a foot of water that afternoon to chest deep on a 6-foot man by 8 o’clock.”

— Jenny Cavenaugh, Turkey Farmer and Antique Dealer, Northeast, North Carolina

“We were behind one another praying to get out of that water.”

— Walter Davis Sr., Retired Dupont Employee, Grifton, North Carolina

“It looked like an ocean. I never. It just got me. It looked just like an ocean.”

— Walter Davis Jr., Administrator at the Caswell Center, Grifton, North Carolina

“Our fire department — I think they did an excellent job of getting people out. They worked around the clock, you know, until they got everybody out.”

— Jenny Cavenaugh, Turkey Farmer and Antique Dealer, Northeast, North Carolina

“The only way we got through it: They had a big fire truck. And what it does, it was in front of the cars; and it would sort of wave the water off with the cars coming behind. It was making a path for us.”

— Walter Davis Jr., Administrator at the Caswell Center, Grifton, North Carolina

“When Aaron came out from the river house he was rescued. Some boys went down and got him with a boat.”

— Jenny Cavenaugh, Turkey Farmer and Antique Dealer, Northeast, North Carolina

“We heard that [our community] was quarantined, and then we heard it wasn’t quarantined. And then we heard that they advised you not to go back. And then we heard, wait until the water goes down and you can go back.”

— Ava Cavenaugh, Registered Nurse, Northeast, North Carolina

“The next morning I had to go check the farm, the turkeys, which they were all dead when I got there. And the water probably had come up at least 5 foot during the night, drowned all the turkeys, flooded the antiques. It was just more than we expected. We didn’t just — disbelief. We didn’t believe that, but it did happen.”

— Aaron Cavenaugh, Turkey Farmer, Northeast, North Carolina

“Right sickening to be out there and to float them animals out and shoot your goats to keep them from drowning. I mean, it was terrible. I’d shoot a goat and cry. Shoot a goat and cry.”

— Jim Connors, Hog Farmer, Near Holly Shelter Creek, North Carolina

“He was an Amish horse. He was a saddle-bred horse. A good buggy horse… And he was in water probably up to his knees, and we just hooked a lead line to him. And we were in the boat and we just led him all the way… for about probably five miles to a higher ground where he was safe.”

— Aaron Cavenaugh, Turkey Farmer, Northeast, North Carolina

“It was like everywhere that I went there was devastation. The house was devastated… And we didn’t see anybody. We’d see our friends and our neighbors all along the road. But nobody had time to stop and say, ‘How are you? Do you need anything?’”

— Jenny Cavenaugh, Turkey Farmer and Antique Dealer, Northeast, North Carolina

“I was wrestling two-hundred-pound feed bags and chest waders going from building to building. Then I had my johnboat with a generator in it and a submersible pump, and I was dropping it over the side filling feeders up to the water.”

— Jim Connors, Hog Farmer, Near Holly Shelter Creek, North Carolina

“When I first got in the air to [fly over] what happened, my first feelings were of disbelief… Hog waste is this particular color of pink, it looks like Pepto Bismol — I hate to use that name because I don’t want the company to get a bad rap — but it looks that color, and you could see it running off into the river. You could follow it down from where the floodwaters were right on down to the river. We flew over the junkyards and we could see these huge plumes of oil and gas and antifreeze and different chemicals washing out of the junkyards, and there’s lots of junkyards in the flood plain. We could see these fuel storage areas for farms and industry had gotten hit and you could see these oil drums leaking, just tremendous amounts of fuel down the river. And then even from farm houses and things you could see the chemicals coming out of the barns, you know, where the waters had gotten inside. You could see dogs on top of the roof of a car. All you could see was the top of the roof of the car and you could see a dog there. You’d see people standing on the porches of their houses, the house completely surrounded by water, no way to get in and out, and sitting on a rocking chair on the porch, rocking back and forth. But that’s the kind of thing we saw: pollution, people’s pain, the loss of property. I mean it was a terrible sight.”

— Rick Dove, Retired Neuse River Keeper for the Neuse River Foundation, New Bern, North Carolina

“I hadn’t had any taste for fish… because a friend of mine, he lived over in Pitt County, and he said when he went on his porch with his boots on, he could see fish going across his porch.”

— Walter Davis Sr., Retired Dupont Employee, Grifton, North Carolina

“In the beginning there was nothing… We had 60,000 dead turkeys… Every bit of income we had, every business, everything we owned was under water… There was no time to go stand in line to see if Salvation Army would help you or the Red Cross could help you. It was needless to go for food stamps.”

— Jenny Cavenaugh, Turkey Farmer and Antique Dealer, Northeast, North Carolina

“When you came back, it wasn’t like people could just come and stay. You had a two-hour time limit. They had the National Guard patrolling and you got your little ticket and everything. And if your time limit was up, they came looking for you.”

— Walter Davis Jr., Administrator at the Caswell Center, Grifton, North Carolina

“I was here thinking that I could save our floors and walls. So I was trying to dry them out with the dehumidifiers. And I was trying to spray Clorox on everything.”

— Jenny Cavenaugh, Turkey Farmer and Antique Dealer, Northeast, North Carolina

“They said throw away all your plastic stuff, your paper stuff, your wooden things that got contaminated. Throw away everything except maybe something like stainless steel that you could bleach.”

— Ava Cavenaugh, Registered Nurse, Northeast, North Carolina

“In the beginning there were times when churches would come by. I know Pinhook Church or Oakdale Church — I think it was Oakdale Church came by one day and it was around lunchtime. They stopped in our driveway. It was two ladies. And they had brought us some paper towels and things from their church. And I was so glad because I hadn’t had time to go get any. And out she brought some potted meat. And Aaron said, ‘Well I just want some potted meat.’ I mean anything that you could just pop the top on a can. That’s what we ate… Even church groups from out in Wallace came. Ladies would come in the afternoon after their prayer service. They would come and wash dishes with me for an hour or two hours, three hours. And when they’d come in, I’d just say, ‘Go pick a section. Here’s some gloves. Here’s a tub. Pick a section and just wash what you want to wash.’ And they acted like they had fun doing it.”

— Jenny Cavenaugh, Turkey Farmer and Antique Dealer, Northeast, North Carolina

“I thought that FEMA was going to help us, and I signed up with FEMA to start with, but I didn’t ever hear anything.”

— Walter Davis Sr., Retired Dupont Employee, Grifton, North Carolina

“When I got to my father’s, 40 head were there [to help clean out the house]. And there were all my pictures and slides and stuff. And they were just chucking them. There wasn’t much I could do… strangers taking that stuff out. Then they tell you that they’re going to go to your house to do the same thing. And by the way, the wrecker man is here to haul your cars off… There was busloads of people helping everywhere. I mean, it was like a war zone.”

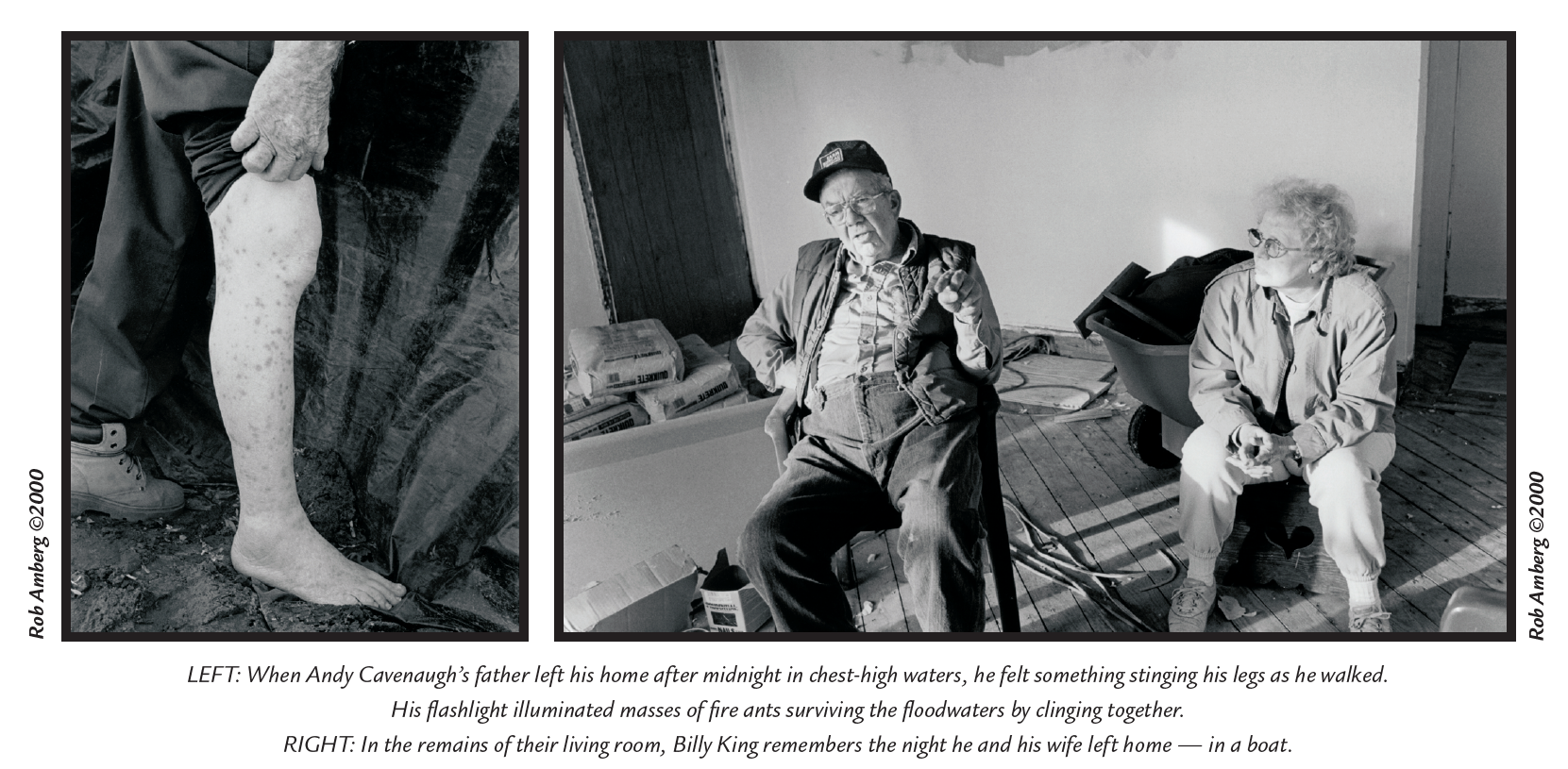

— Andy Cavenaugh, Flower Farmer, Northeast, North Carolina

“The FEMA inspector that came here — very arrogant, rude. He was not interested. And I think our $2,855.10 showed that. He was not interested in us at all. He came from California, a very rude man… And he punched some numbers on a little handheld computer… I had the same amount of water that I know another lady had. She got $9,000 and I got $2,855. I’m glad the lady got the money. There’s not a problem with that at all. But I know we weren’t paid enough even to make it safe and livable… FEMA and they said we could save everything. Well we couldn’t… The walls were spongy.”

— Jenny Cavenaugh, Turkey Farmer and Antique Dealer, Northeast, North Carolina

“I’ll tell you the truth: the flood is no worse than this rigmarole, red tape what you go through afterwards.”

— Frank Cavenaugh, Retired Farmer, Northeast, North Carolina

“One Sunday we come riding by here and we seen a brand new Jeep parked up in our yard. We thought it was somebody else come to help… We was coming back from the Red Cross and pulled in here. And [the people with the Jeep] were loading up our stainless steel. They were stealing. Had all my stainless steel cookware loaded up and all my children’s toys loaded up.”

— Ava Cavenaugh, Registered Nurse, Northeast, North Carolina

“The whole thing brings out the good and the bad in people. This gentleman gave me $50 right out of his pocket. Told me I needed it. And I don’t even know who he was.”

— Andy Cavenaugh, Flower Farmer, Northeast, North Carolina

“He came to the door and he said, ‘I’m with the North Carolina Department of Revenue.’ And I said, ‘Well, son, I think I mailed my sales tax and paid all my taxes.’ And he said, ‘Well I didn’t come to collect.’ And I said, ‘Well, what can I help you with?’ And he said — and by then I had invited him in — and he said, ‘I’ve come to help you.’ And I said, ‘You’ve come to help me?’ And he said, ‘Yes, ma’am… Anything that you want cleaned up pertaining to this flood.’ They were good help, too.”

— Jenny Cavenaugh, Turkey Farmer and Antique Dealer, Northeast, North Carolina

“Never thought I would meet anyone from Pennsylvania. This group came down here and worked like Turks to serve me — who has nothing.”

— Kathleen Bratten, Family Caretaker, Tick Bite, North Carolina

“The governor, on ABC News — I’ll never forget it as I sat there, and I just sat there in disbelief for about 10 minutes after I heard him make this statement — but he had the president by his side… He threw his arms open and he looked around to all these people, including this one little kid who the camera focused on afterwards, and he said, ‘There wasn’t anything that we could do to prepare for this.’ And I think Governor Hunt’s a pretty good fella, and I’m not mad with him or anything, but that was a dumb statement. Because there is a lot we could have done to prepare for this.”

— Rick Dove, Retired Neuse River Keeper for the Neuse River Foundation, New Bern, North Carolina

“The Salvation Army truck would come through our community. And they would stop and they would have like a box lunch with a drink… But that hot meal when they would pass it out that window, I never ate anything that was bad that came off that truck. Everything that we ate was delicious.”

— Jenny Cavenaugh, Turkey Farmer and Antique Dealer, Northeast, North Carolina

“It’s hard to stand in line and wait for somebody to tell you, ‘You can have this, and you can’t have this.’ And you’ve worked all your life, and you’ve always been the one to give.”

— Elder Bert Picket, Pastor of Mount Pleasant All Saints Pentecostal Holiness Church, Wallace, North Carolina

“Hands have been the biggest asset that anybody — if you’ve ever been flooded, hands are what a person needs. They need financial stuff, too. But in the very beginning — those hands. You don’t even know what you need financially but you know you need hands, because your mind is working so much faster than your hands can keep up.”

— Jenny Cavenaugh, Turkey Farmer and Antique Dealer, Northeast, North Carolina

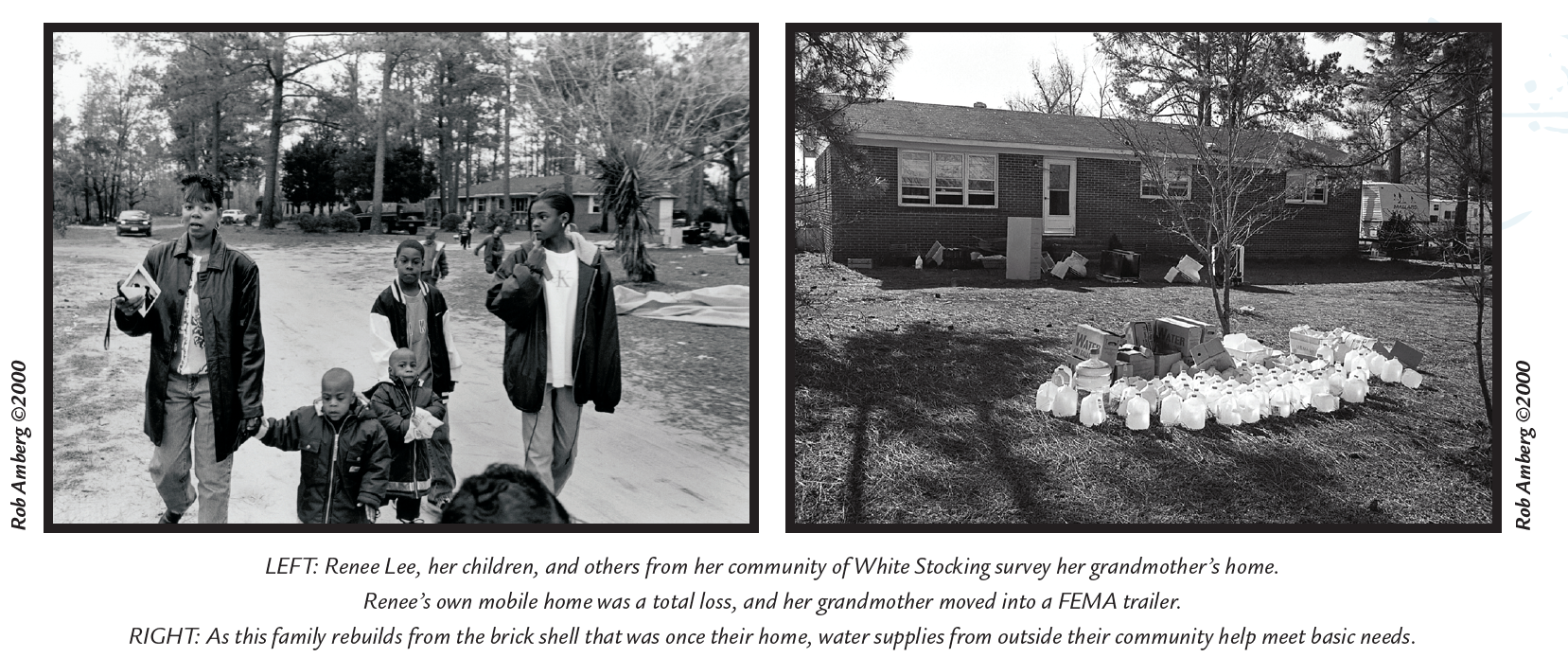

“We have joined an organization here in the county called SOC. And that stands for ‘Strengthening Our Communities.’ And we want to know the situation… When money comes to the county we will be able to… distribute it to the people that really has a need.”

— Elberta Hudson, Assistant Pastor of White Stocking A.M.E. Zion Church, White Stocking, North Carolina

“Governor Hunt, when he got his money, the governor’s relief fund, he sent out checks. And you went down and you signed your name up and he gave everybody the same amount… I got 300-and-some dollars the first time, a hundred-and-some dollars the second time and $308 the last time… Jim Graham, our commissioner of agriculture, took up a farmers’ disaster relief fund. And he said that every dollar would be given to the farmers. And I know that we did receive money from Mr. Graham, and we greatly appreciate it. I wrote him a thank-you note.”

— Jenny Cavenaugh, Turkey Farmer and Antique Dealer, Northeast, North Carolina

“The flood has brought some good changes because I think once — well now when you meet people that you know now, a lot of times people would see you and wouldn’t say anything, just — they know you but they wouldn’t go out of their way to say something to you. But now I think it’s more united again. Everybody… we’re glad to see each other… Everybody’s on the same playing field… Brought us all down to the same level.”

— Walter Davis Sr., Retired Dupont Employee, Grifton, North Carolina

“This was in fact a 50-year rain event that caused a 500-year flood event. And to understand what’s happened here, is in the last 50 years in order to develop all over this state, eastern North Carolina in particular, we have changed the landscape. We’ve put Mother Nature out of balance. I guarantee you when this storm rolled in here this time with this rain, Mother Nature didn’t recognize this place… We have filled the wetlands as if they were trash… We filled them to build shopping centers. We cut down the forests to build shopping centers and schools. In doing that we’ve let the sediments go down to the river to shallow the river… So when Mother Nature rolled in here this time with this rain, there was no holding capacity. It all ran right to the river… Mother Nature couldn’t deal with it except by pushing it over her banks as she did. And I don’t think we should be surprised about that.”

— Rick Dove, Retired Neuse River Keeper for the Neuse River Foundation, New Bern, North Carolina

These interviews and some of the photographs appeared in different form in Southern Cultures, volume 7, number 3. © Center for the Study of the American South. Used by permission of the publisher: uncpress.org. A portion of the content also previously appeared in the January/February 2001 NC Crossroads, a publication of the North Carolina Humanities Council. “The Great Deluge” draws from interviews from the Southern Oral History Program. Founded in 1973 by historian Jacquelyn Hall, the SOHP is part of the UNC Center for the Study of the American South. The SOHP Collection in UNC’s Wilson Library, more than 6,000 interviews strong, is one of the nation’s most valuable oral history archives.

- Categories: