If COVID-19 and a Major Hurricane Collide

What would it mean for people living in our state’s most vulnerable communities?

Hurricane Isaias already left damage that spanned the East Coast, and the coronavirus continues to cause chaos. With forecasters having predicted an above-normal hurricane season, can North Carolina’s most vulnerable communities face both a serious storm and a pandemic?

Traffic snarled in Wilmington on July 11 as hundreds of vehicles lined up to receive free hurricane preparedness toolkits.

After three major hurricanes in 36 months, officials say the tremendous response to the toolkits shows that people are taking the threat of another hurricane seriously.

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration predicts a 70% chance that this hurricane season will bring 19 to 25 named storms, with seven to 11 of those becoming hurricanes — including three to six major hurricanes. By early September, 15 storms already had been named this season, with more on the way.

In less turbulent times — those with cooler oceans and without the dampening effects of an El Niño — the typical prediction would be 12 named storms, with six becoming hurricanes.

North Carolina, like other states, has struggled to recover from the aftermath of one hurricane after another. Now it faces a much bigger challenge: the likelihood that a major hurricane will hit the coast during a pandemic of the highly contagious coronavirus.

Mike Sprayberry, director of the state Department of Public Safety’s Emergency Management, said COVID-19 adds many new and unwanted challenges, especially with shelters.

He said his agency has “a good, solid plan” to deal with a hurricane during these troubling times, but he didn’t downplay the seriousness of the additional problems a major storm could create this year.

“It’s important to be concerned,” Sprayberry said. “Not worried, just concerned.”

In July, he said, Emergency Management and other state agencies held a virtual teleconference to update and hear concerns from about 300 people — including local emergency management officials, first responders, National Guardsmen, volunteers, and many others — on executing the plans for hurricane preparedness and recovery.

Normally, Sprayberry and officials from other state agencies would take their show on the road, making in-person visits before representatives from counties, cities, and towns in hurricane-prone areas.

What Social Distancing Means to Shelters

Virtual conferencing is just one way that the pandemic has influenced the state’s hurricane preparedness planning. Others include maintaining safe distancing in shelters, a potential reduction in disaster relief from other states, preparing to deal with already crowded hospitals and exhausted medical personnel, and ensuring that people have places other than shelters to ride out the storm.

Perhaps the biggest challenge should a hurricane strike is safely operating and maintaining evacuation shelters, Sprayberry said. To provide adequate social distancing, the state has limited the shelters to 115 square feet per person.

Natosha Vincent, Wilmington’s emergency services coordinator, said that means the four shelters designated for her city cannot hold a total of more than 235 people. During Hurricane Florence, Vincent said, those same shelters had a capacity of about 600 people.

Although no one would be turned away, Vincent said, the city is encouraging people who might have even a remote chance of having to evacuate to a shelter to make arrangements now to stay with family or friends who live inland.

Sprayberry said the state has plans in place to open more shelters if needed, a difficult task even without the pandemic because it is usually done with little advance warning.

Because of the coronavirus, Sprayberry said, shelters are being viewed as “a last resort,” to be used primarily for people with nowhere else to go. Unlike in the past, cots won’t be provided to maximize space, and people will have to bring their own bedding, Vincent said.

Sprayberry called shelters — and the possibility that such close living quarters will lead to a spread of the coronavirus — his “greatest concern.”

As an alternative to shelters, Sprayberry said the state has identified more than 30,000 non-congregate living quarters for people forced to evacuate, including rooms in motels and dormitories farther inland.

Although still awaiting approval from the Federal Emergency Management Agency, Sprayberry said, the state plans to establish reception areas where low-income people in high-risk areas could go before evacuating to learn which motel or dormitory would accommodate them.

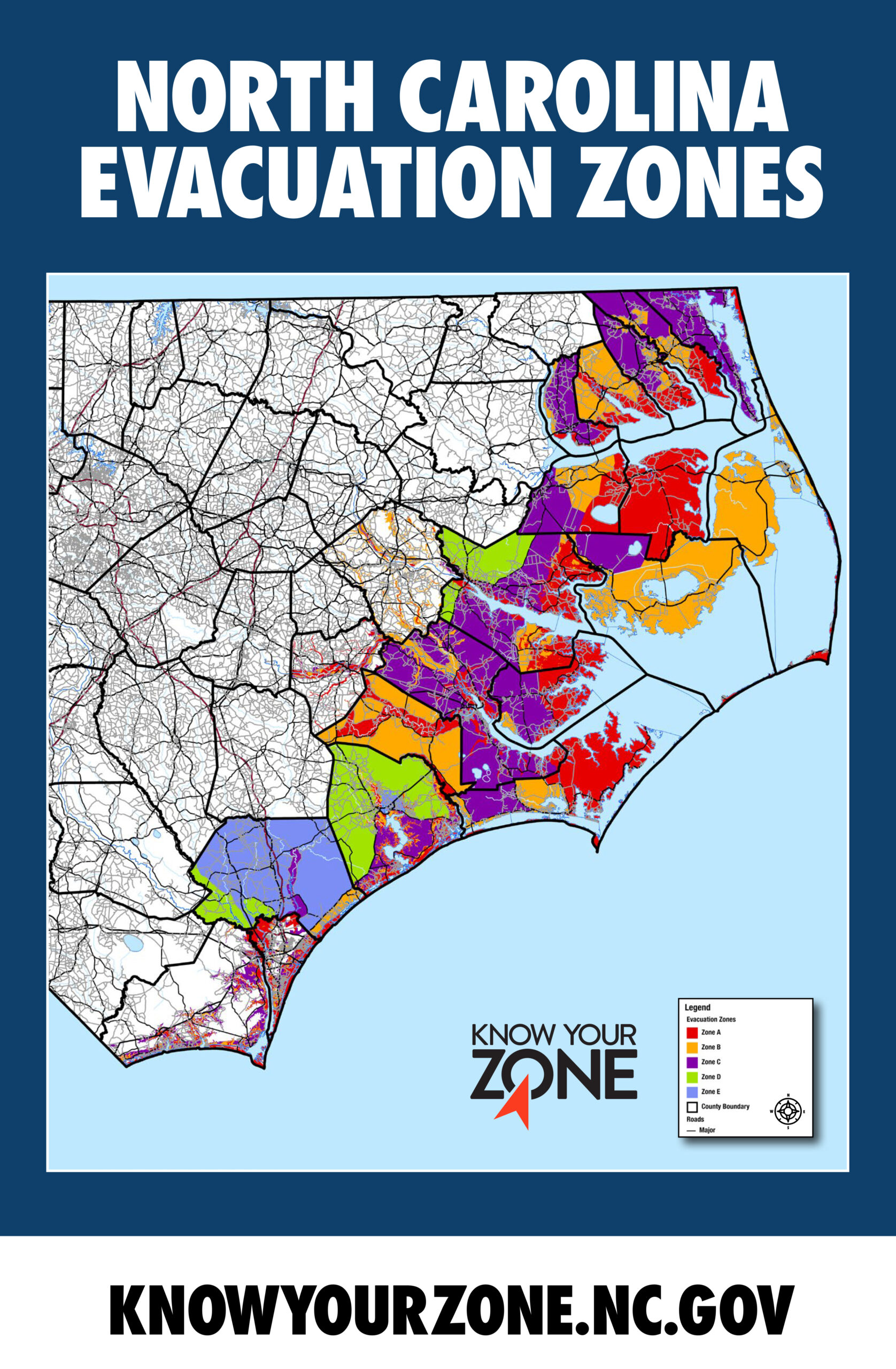

The state has also created evacuation zones in an effort to make evacuating faster, more organized, and efficient. (See Know Your Zone below or here.) The zones can be found on a new interactive website, including a version en Español, which will also update evacuation orders for the zones. In addition, ReadyNC has a comprehensive website that provides information about storm preparedness, evacuations, shelters, recovery, and the coronavirus.

Does North Carolina Have Enough PPE?

Sprayberry said he is less concerned about the availability of face masks and other personal protective equipment should a hurricane strike. The state now has a significant amount of PPE in its warehouses, compared with the shortage that happened in March and April, Sprayberry said.

“I’m not going to say comfortable, I’m going to say I’m not alarmed right now and I think it’s something that we need to monitor closely and to make sure that we have a good plan in place,” he reported in July. “Right now, we have a significant amount of PPE in stock, but we can’t take our eyes off the ball.”

Sprayberry said local government officials can order more personal protective equipment from the state with no questions asked.

“We’re not stopping ordering because we know that we’re going to need it for building our strategic state stockpile for PPE.”

High Risks for Marginalized Communities

People living in marginalized communities — typically poor minorities in low-lying, flood-prone areas — are the most susceptible to the coronavirus and to major storms. Many of those people lack transportation or friends and family living inland where they could go to seek shelter from a hurricane.

“One of the things that stands out to me about North Carolina, specifically, is that the risks and the vulnerabilities of those folks who are least able to manage those risks are so high,” said Elena Craft, senior director of climate and health for the Environmental Defense Fund. “For example, the low-income minority populations, especially in eastern North Carolina, and the impact of the underlying disease factors that also contribute to the risk for coronavirus infections.

“We think of it as a double or triple whammy, where they’re at increased risk for having a severe coronavirus infection. They are more likely to have jobs where they’re potentially exposed to coronavirus, less likely to have access to health care. It’s just a tsunami of different variables that all contribute to sort of higher risk,” she said. “Then you obviously add the impact from hurricanes.”

Sprayberry is aware of those concerns.

“We always make plans for transportation,” he said. “We can get buses. We have to put less people on the buses than normal. So what would be critical during a time like this is to ensure that if an evacuation order is going to be made, that it’s done timely enough so that we have an orderly response that helps us maintain social distancing.”

Betsy Albright, chairwoman of the Environmental Economics & Policy Program at Duke University’s Nicholas School of the Environment, said the issue goes far beyond ensuring that people living in marginalized communities can safely evacuate. Albright spoke during a July 1 webinar hosted by the university, titled “Perfect Storms: Responding to Hurricanes While Addressing COVID-19.”

“We know that low-wealth communities and communities of color are disproportionately affected by COVID-19, both in health and economic impacts,” Albright said. “The impacts of hurricanes are amplified disproportionately across race, due to centuries of institutional and systemic racism. Further studies have documented inequitable access to resources for hurricane recovery across race.

“So all this taken together, the risk of hurricanes will magnify risks of COVID, and vice versa, with more significant impacts on communities of color, under-resourced communities, and people who are living or working in congregate facilities, nursing homes and correctional facilities, meat processing facilities, etc.”

The Feet on the Ground

Dawn Baldwin Gibson has worked in disaster relief efforts since Hurricane Irene struck the North Carolina coast in 2011. She now heads a task force for N.C. Voluntary Organizations Active in Disasters, is the administrator for a 5,657-member Facebook group called Eastern NC Disaster Resources, and is a superintendent at Peletah Ministries in New Bern.

In short, she is among the leading voices on the ground in eastern North Carolina taking charge of efforts to provide information, resources, and disaster recovery to impoverished minority communities.

Baldwin Gibson tells a story that begins shortly after Hurricane Irene, while she was helping to hand out food in hard-hit areas. She said she came upon a man who thanked her for the food and then asked, “What about my dog?” With no food left in his home, the man had resorted to eating dog food.

Baldwin Gibson said hurricane preparedness and relief efforts have improved markedly since then.

“We’ve taken this community approach that it has to happen in communities,” she said. “We need government. We need emergency management. We need these state agencies. But we also have to have communities that are at the table.”

Baldwin Gibson noted an event scheduled for late July for hundreds of people to receive free healthy food, hurricane preparedness toolkits, and information on how to prepare for a storm.

“What we need is for this information that we’re getting from the governor’s office, from Director Sprayberry’s office … to make sure that it’s getting to everyone that needs to be getting it,” Baldwin Gibson said.

Will the Calvary Come?

Typically, just after a hurricane hits in North Carolina, help will come pouring in from other states, and sometimes even before the storm. That assistance includes swift water rescue boats and personnel, medical professionals, church organizations, utility crews, and the like.

Because of the pandemic, Sprayberry said, that may not happen with the same intensity as in the past, especially when it comes to medical workers. Other states now have their own problems to deal with, he said.

Baldwin Gibson said one of her biggest concerns is a lack of linemen from other states to help restore power.

“If that doesn’t happen then we’re talking about how we may be without electricity for much longer periods of time,” she said. “What does that look like in marginalized communities?”

Baldwin Gibson said her biggest worry is that people become so focused on dealing with the pandemic that they forget just how important it is to prepare for a hurricane.

“My greatest concern is that we are so focused on the disaster of COVID-19 that we don’t understand how we must stay prepared for hurricane season,” Baldwin Gibson said. “That is my overwhelming concern, and I am appreciative that the information is being pushed out, but this is really going to have to be something that we’re doing at a community level, that we are working with our local agencies and our local officials to make sure that everyone understands the seriousness of what we are facing.”

Text reprinted courtesy of North Carolina Health News, updated and edited for format and space.

North Carolina Health News is an independent, non-partisan, not-for-profit, statewide news organization dedicated to covering all things health care in North Carolina. Visit NCHN at www.northcarolinahealthnews.org.

Know Your Zone

A New Evacuation System for Coastal NC

By Dabney Weems

Know Your Zone, North Carolina’s new system of coastal evacuation zones, launched earlier this summer. This tiered evacuation system focuses on areas most vulnerable to impacts from hurricanes, tropical storms, and other hazards.

The campaign was implemented to simplify the evacuation process by assigning lettered evacuation zones in each county, based on areas of higher and lower risk of flooding.

How Does it Work?

Local governments in 20 North Carolina coastal counties have drawn pre-determined evacuation zones. As storms approach, local officials will determine which zones need to be evacuated and will order evacuations using the lettered zones.

North Carolinians can learn their zone by entering their address into an interactive map. You can find the zone for your workplace, children’s school, and/or your loved ones, too. Visit KnowYourZone.NC.gov.

During an Emergency

Local officials will determine which zones should be evacuated. Areas in Zone A will typically be evacuated first, followed by areas in Zone B, etc.

While all zones won’t be evacuated in every event, emergency managers will work with local media and use other outreach tools to notify residents and visitors of impacted zones and evacuation instructions. Residents should look and listen for their county name and zone when evacuations are ordered.

Tell Your Neighbors

Once you learn your zone, the website has plenty of resources to share with your community. Social media graphics, posters, and even a children’s activity packet are available to download here. Use them to help spread the word about Know Your Zone.

The more people who know their zone, the smoother the evacuation process becomes.

- North Carolina Hurricane Guides

KnowYourZone.NC.gov

ReadyNC.org - Know Your Zone en Español