North Carolina’s Blue Economy: Rural Economic Development in the Coastal Region

Why are some coastal rural counties thriving while others are struggling?

North Carolina’s Blue Economy information series provides updates related to the state’s ocean economy and underlying natural resources. Jane Harrison, North Carolina Sea Grant’s coastal economist, has published four editions online, including this issue on rural economic development. go.ncsu.edu/Blue-Economy

Rural Communities near North Carolina’s coasts are neither consistently prospering nor uniformly in decline. Although rural areas have some distinct economic attributes, they also increasingly mirror development patterns in more populated locals.

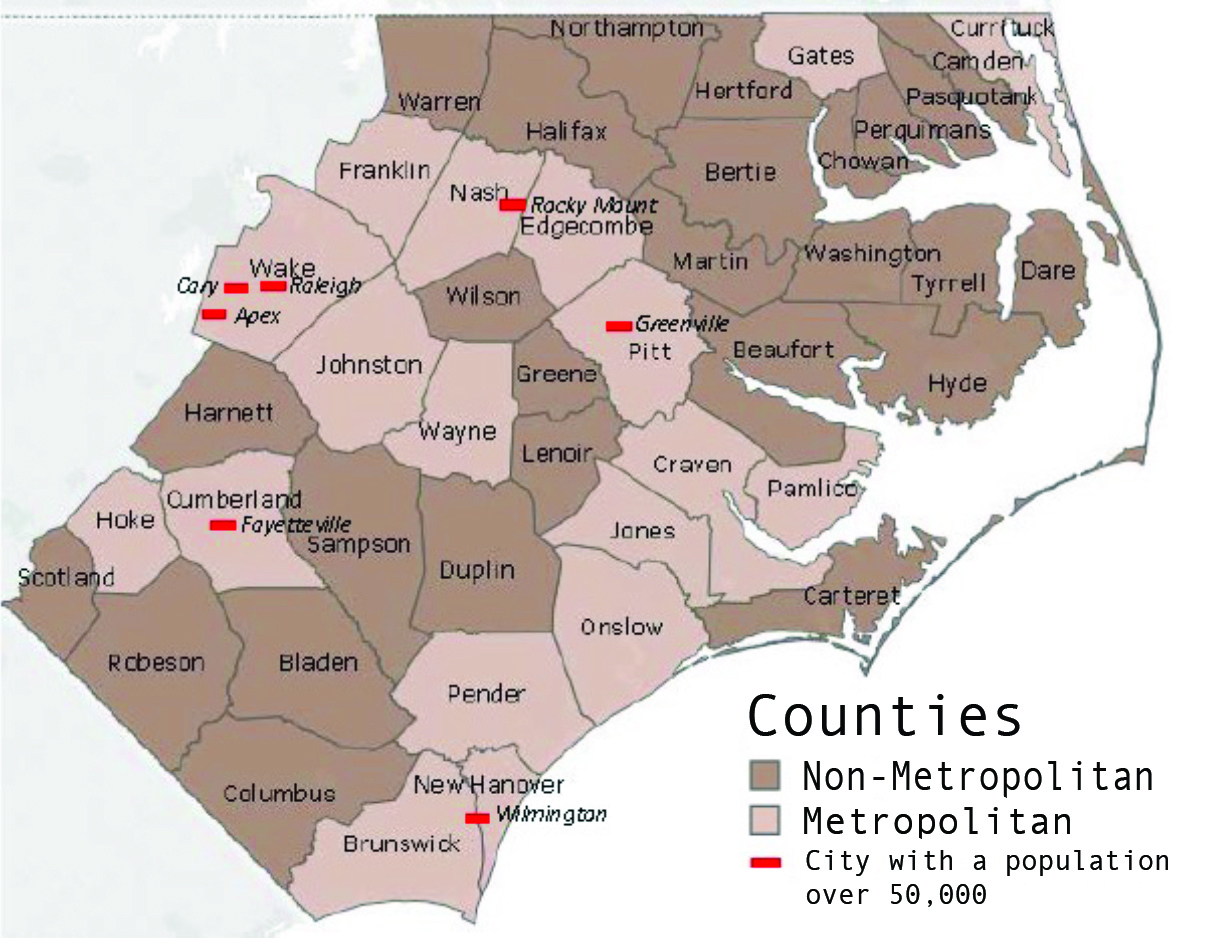

A far distance to markets, low population density, and an abundance of natural resources are distinguishing features of rural places. Typically, a rural community is part of a non-metropolitan statistical area that contains cities with populations under 50,000 and that have a high degree of economic and social integration.

There are two rural areas in the coastal plain, as defined by U.S. Census Bureau statistics. The Northeast Coastal non-metropolitan area includes Bertie, Camden, Chowan, Dare, Halifax, Hertford, Hyde, Martin, Northampton, Pasquotank, Perquimans, Tyrrell, Warren, and Washington counties. The Southeast Coastal non-metropolitan area includes Beaufort, Bladen, Carteret, Columbus, Duplin, Greene, Harnett, Lenoir, Robeson, Sampson, Scotland, and Wilson counties. (See the dark brown counties in Figure 1.)

Rural Population Trends

Migration patterns — the movement of people from one place to another — are one indicator of the economic health of rural areas. Population growth is generally associated with economic growth but comes with its own challenges, such as new infrastructure needs and increased demand for public services. In addition, high levels of migration, whether into or out of an area, can lead to unemployment, depending on how businesses grow or adapt to change.

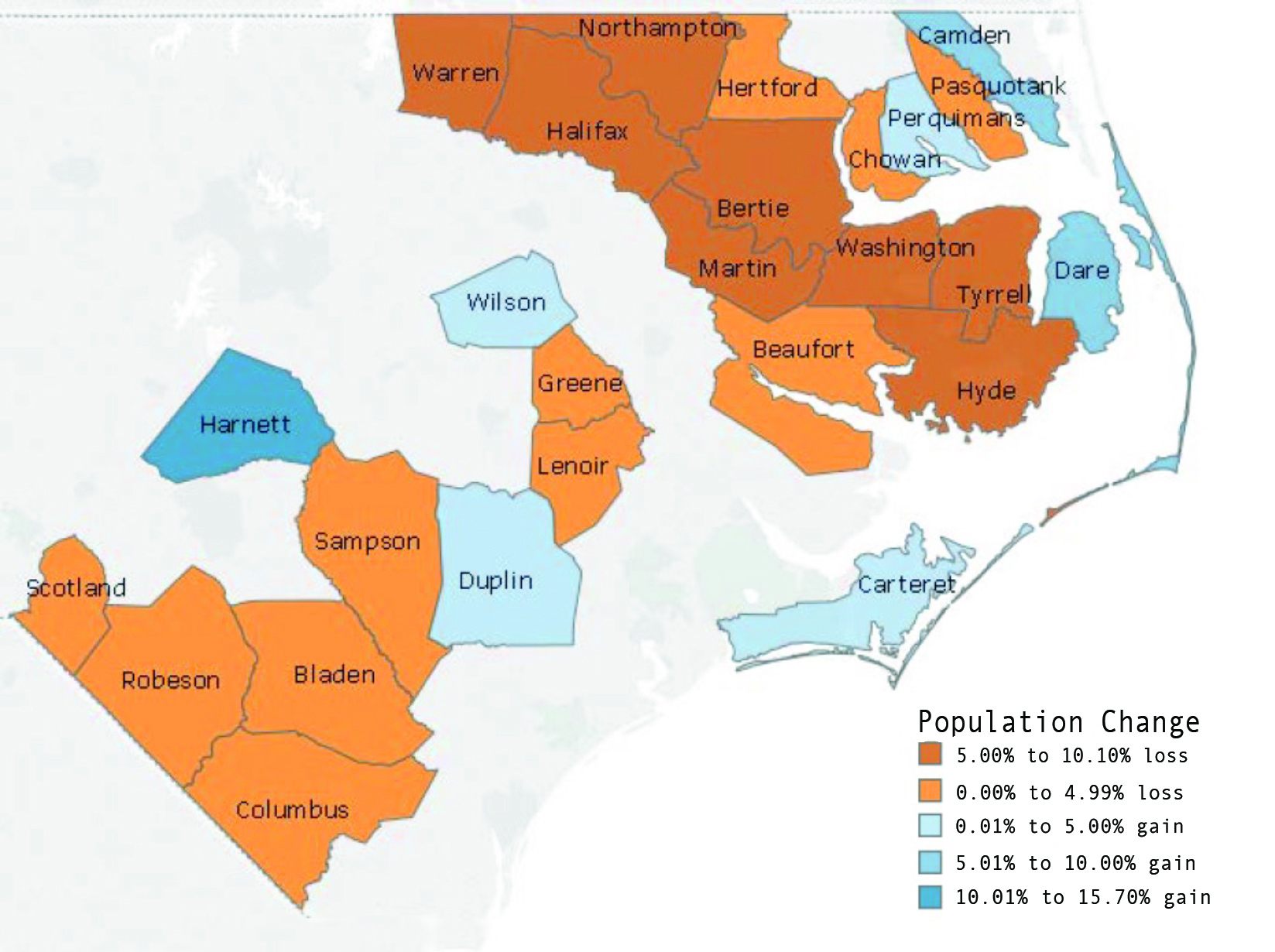

Retirement destinations like metropolitan Brunswick and Pender counties are some of the fastest-growing areas in the state, while the least populated counties continue to experience population loss.

In fact, the majority of the non-metropolitan counties in the coastal region have lost residents since 2010. (See the counties in orange in Figure 2). Eight of those counties lost more than 5% of their population during this time: Northampton (-10.1%), Washington (-9.1%), Bertie (-9.7%), Tyrrell (-8.1%), Hyde (-7.8%), Martin (-7.0%), Halifax (-6.1%) and Warren (-5.4%).1

The composition of the rural workforce is evolving, with new demographic groups seeking out employment opportunities. Latino migration to the rural coastal region increased significantly between 2000 and 2010, resulting in a doubling, on average, of the Latino population. Although the total population of Latinos is often smaller in rural areas than urban areas, the proportion of Latinos is often greater in rural places. For example, as of 2010, Latinos made up 20.6% of the population in Duplin County, 16.5% in Sampson, and 14.3% in Greene, whereas they made up 10.2% of the population in metropolitan Wake County.

Three Types of Rural America

Prosperity in the coastal region is uneven, with some communities still struggling to make economic gains since the Great Recession of the late 2000s. Rural America is comprised of three distinct areas: (1) “high-amenity” rural regions, (2) “urban- adjacent” rural places, and (3) remote rural communities.2 It is the last that has typically struggled, while rural areas with high amenities and access to urban labor markets generally experience greater population and economic growth than their remote counterparts.

High-Amenity Rural Areas

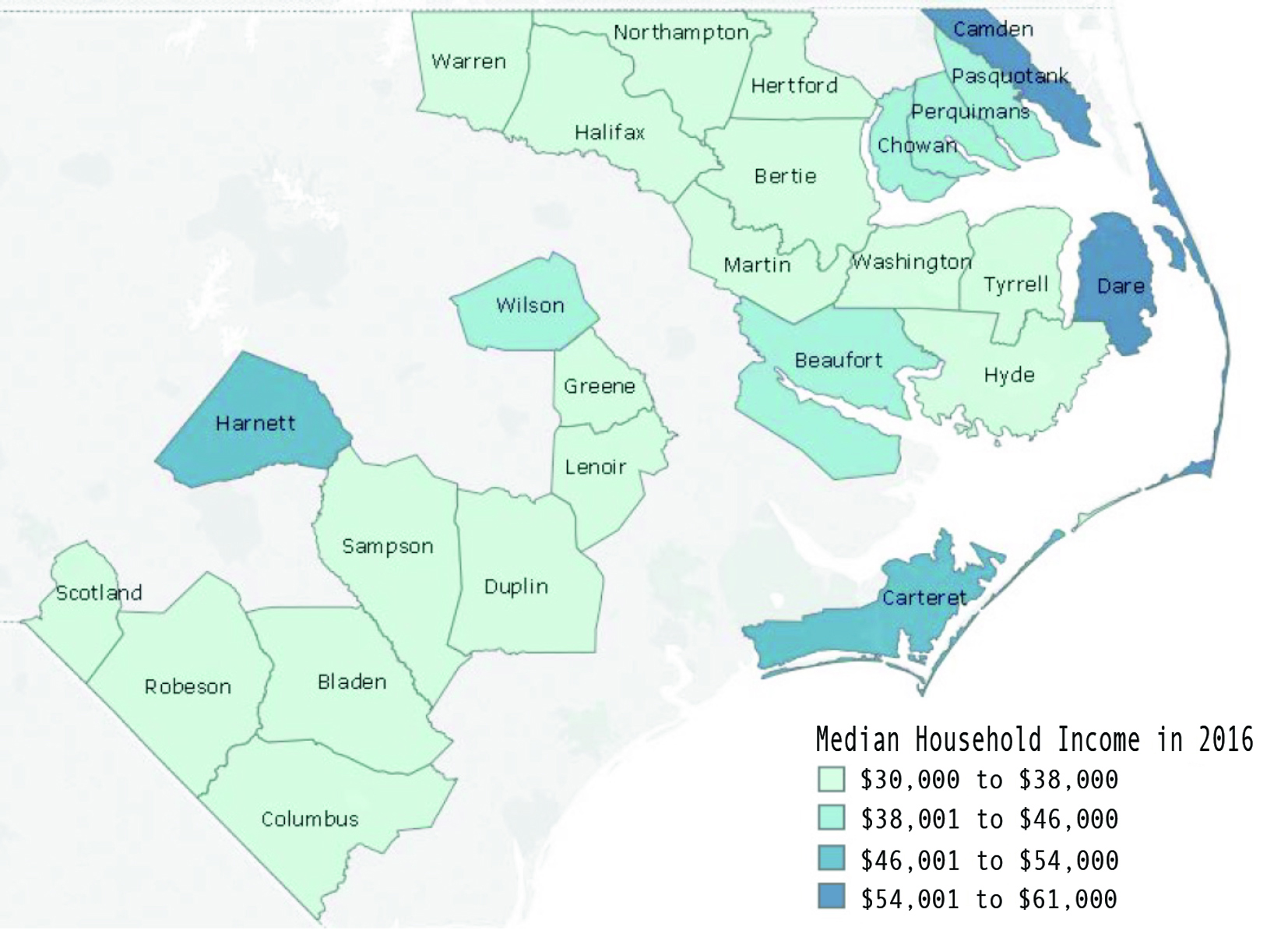

Amenities and quality-of-life increasingly influence rural migration flows and business development. Natural amenities, like attractive scenery and recreational opportunities, draw people to rural areas and have boosted the wealth of many waterfront communities. As a result, median household income in the rural counties closest to the coast — Camden ($60,714), Dare ($54,787) and Carteret ($50,599) — are all higher than the state average of $48,256.1

High-amenity rural areas typically have experienced substantial economic and population growth. In the 1990s, in-migration began to outpace natural population growth — the number of births minus the number of deaths.3 In addition to wealth transfer, which can serve as financial capital to invest in new and existing businesses, population growth in these communities is generally associated with new jobs in construction and higher demand for employees in retail and commercial services.

Downsides of this population gain include higher costs of living — driven by increased demand for housing — and greater traffic congestion.

Urban-Adjacent Rural Areas

Rural communities have benefited from the proliferation of automobiles and improvements in transportation infrastructure, which allow for more rural- to-urban commuting. For rural areas located near metropolitan areas, access to urban employment is an important cause of population retention and growth. For example, non-metropolitan Harnett County sits between metropolitan Wake County to the north and Cumberland County to the south, making work possible in cities from Raleigh and Fayetteville.

Over time, the population growth rates of metropolitan counties have increased in comparison with non-metropolitan counties. However, this trend in part reflects how rural communities that experience significant population growth often get reclassified as metropolitan themselves.

Remote Rural Areas

Remote rural communities in the coastal area face fewer employment opportunities and longer distances to urban areas. Traditionally their economies are resource-based, dependent on harvesting or extracting natural resources with little or no processing. Generally, more remote places have the lowest median household incomes. (See the counties shaded in lightest teal in Figure 3.)

Lower-income communities also usually have lower costs of living, which can help to offset this deficit. That said, lagging rural regions are likely to be geographically remote, with poor infrastructure, low population density, and limited employment opportunities.

Remote regions in the coastal plain traditionally have depended economically on agriculture and manufacturing. Labor-saving technologies in both industries have reduced the need for workers. In Lenoir County, for example, manufacturing employs 25% of the workforce, whereas statewide this sector only employs 12% of the labor force1, and the county’s population declined by 4.4% from 2010 to 2017. Employment in manufacturing bottomed out nationally in 2010, and recovery after the Great Recession has been slow in places that depend on either of these industries.

Regional Development Drivers

Understanding why businesses locate where they do helps to explain why some rural regions prosper while others languish. Businesses locate where they can maximize profit, which often depends on regional uniqueness and comparative advantage.

A region’s uniqueness is based on the availability and productive use of essential assets for production, such as land, labor, and capital. Land is related to climate, growing season, and soil types. Labor pertains to the workforce and its skillsets. Capital consists of the monetary resources available to invest in a business or to purchase goods. The assets in a community affect its development path.

Some assets, such as land or natural resources, are unique to a place and influence the types of businesses that can succeed. For example, oyster farmers must locate their operations in waters with appropriate salinity levels, but this coastal environment cannot easily be replicated artificially.

Other assets, like labor, are more productive when used in combination with certain technologies or physical infrastructure. Consider a single shrimper with a 20-foot boat who can haul in 2,000 pounds of shrimp in a night. If he adds one additional crew member, he won’t increase his landings. He needs a bigger boat to productively use that additional labor.

The size of a business operation and the markets it can sell to impact its effectiveness and efficiency. The cost savings from an increased level of production — “economies of scale” — mean, for instance, that a seafood processor with sizable business volume can bulk-purchase supplies at a lower rate than a smaller-scale competitor.

“Clustered development” — the close proximity of multiple businesses — facilitate economies of scale, as well as spillovers in knowledge that result in innovation. Clustering stems from private sector leadership and government partnerships that drive such outcomes as business and industrial parks. Important industrial clusters in the rural coastal region include aerospace and defense, food processing and manufacturing, and energy, among others.

In pursuing economic development, some communities have a local focus. For example, a rural municipality can increase tax rates to benefit local schools. A town can implement zoning policies that encourage manufacturing firms to locate there.

How a place relates to surrounding areas, though, is also a vital component of its economic success. Rural communities do not develop in a vacuum. Rural areas are, more than ever, integrated into a regional economy and tied to nearby urban centers.

In fact, the economic structures of rural places increasingly mirror their urban counterparts. Most of the rural population does not depend on natural resources for their livelihoods. Today, even rural residents who engage in farming earn most of their incomes from off-farm employment.

Like urban centers, rural areas with significant manufacturing bases develop commerce hubs and advanced supply chains in specific industries to compete with producers globally. Even the most remote rural areas are less isolated than in the past, with ever stronger ties to international markets and labor. Much of the coastal region is located near Interstate 95, facilitating transport of goods to large markets in other states. Deep-water ports in Morehead City and Wilmington provide rural regions with additional market access.

Regional economic integration depends upon robust market relationships and communications between rural and urban areas. Decreasing costs of transport and communication have been a boon to rural areas, yet the quality of these infrastructures continues to be inconsistent. For example, broadband access is still limited in some rural areas, curtailing the types of businesses that can locate there. In the non-metropolitan counties in the coastal region, approximately 60% of households have broadband internet service subscriptions. In metropolitan counties like Wake, Durham, and Mecklenburg, 80% or more rely on broadband.4

Continued Rural Investment

To sustain economic well-being, rural communities must continue to invest in the productivity of unique assets that support economic development. Increased access to high-quality education and workforce development programs can strengthen the labor force. In addition, land and water resources in the coastal region will support further development as long as economic activity is in balance with the capacity of these natural systems. Financial capital will follow where labor and land quality are high.

In coming years, high-amenity and urban-adjacent rural areas that comprise North Carolina’s coastal region are likely to continue to be competitive in a global economy, while more remote rural places may require additional investment to thrive.

References

1 U.S. Census Bureau. 2018. American Fact Finder. https://factfinder.census.gov.

2 Goetz, Stephan J., Partridge, Mark D., and Heather M. Stephens. 2018. The economic status of rural America in the President Trump era and beyond. Applied Economic Perspectives and Policy 40 (1): 97-118.

3 Fulton, John A., Fuguitt, Glenn V., and Richard M. Gibson. 1997. Recent changes in metropolitan-nonmetropolitan migration streams. Rural Sociology 62 (3): 363-384.

4 North Carolina Broadband Infrastructure Office. 2019. Broadband adoption recommendations. https://www.ncbroadband.gov/connectingnc/broadband-adoption.

- Categories: