With a look back at Hurricane Florence, a new study shows how nonprofit leaders responded to the post-disaster needs of the Latina and Latino community in Wilmington, North Carolina.

After completing her Ph.D. and serving with the U.S. Geological Survey for her Sea Grant Knauss Fellowship, Olivia Vilá became a climate resilience planner earlier this year with Linnean Solutions, a New England- based consulting firm that works at the community scale to support sustainability and resilience. The company focuses on physical hazards and root causes of vulnerability.

Vilá says her Knauss Fellowship with USGS, a key federal agency in the resilience space, heightened her interest in bridging national and state- level programs and making them accessible at the local level.

“It opened up a whole new sphere of resources to me that communities should be using and leveraging,” she says.

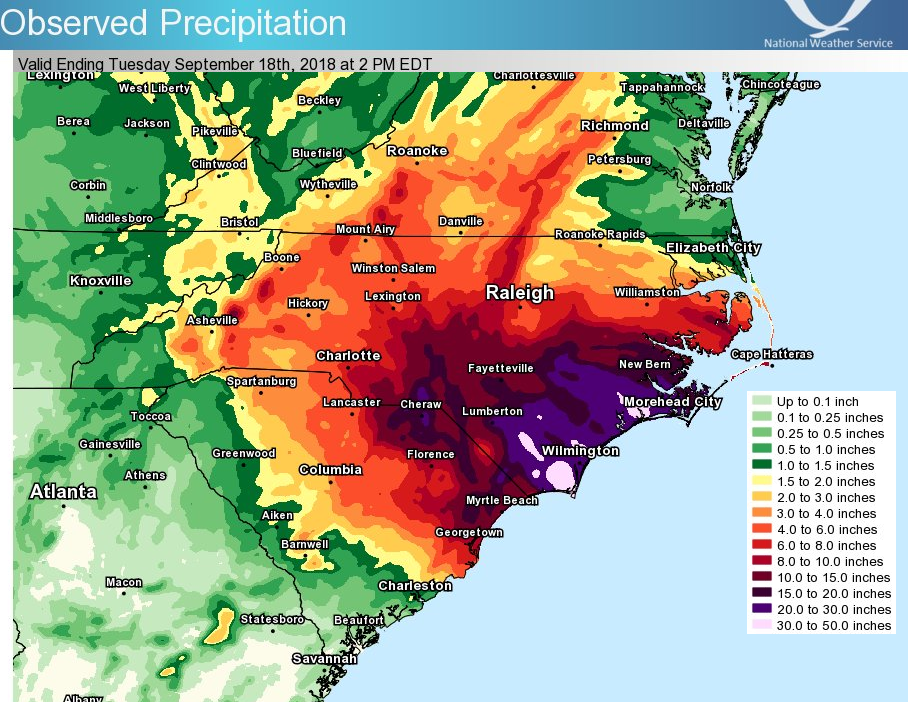

Vilá already had collaborated with several interdisciplinary teams on hazard mitigation and resilience research while completing her Ph.D. at NC State University, focusing on environmental justice, leadership, and policy. During that time, she was a joint fellow with North Carolina Sea Grant and the NC Water Resources Research Institute, and she had begun exploring disaster response and recovery in the aftermath of Hurricane Florence in Wilmington.

“I remember sitting down with these leaders and being really captivated and inspired by all of the things that they do,” she says. “I was excited, too, because I had all this research that technically would be able to help them reach their higher goals and ambitions for their work.”

Her groundbreaking study of the post-disaster response in Wilmington recently appeared in Climate Risk Management, and she discusses it with us here.

Why should we look at disaster recovery through the lens of environmental justice?

Olivia Vilá: This is an important question, because I think people lose sight of the big picture.

Environmental justice involves key questions: How well do we see and understand underrepresented or under-resourced communities? Are there groups that are experiencing more environmental harm than others? Are there groups receiving more environmental benefits than others? Are our policy and decision-making processes more accessible to some groups over others? Is it easier or harder for some groups to actually influence decision-making than it is others?

So, environmental justice initiatives, in turn, often are designed to help a particular group.

But why does environmental justice matter to everyone else?

First and foremost, I believe it is an ethical responsibility for us to support healthy environments free from harm for all people. Thinking about it on an individual level, I would say the answer is very complex, but I think that ultimately if those in our society who are most underserved are not able to recover from disasters, for instance, that’s going to impact everyone at some point. It can strain local economies, exacerbate social and political tensions, lead to public health and safety issues, things like that.

What I would like to see are environments where people now and in future generations are able to thrive, and everyone is able to follow their dreams and their passions and live healthy, meaningful lives. If all people can do that, we create greater potential for our communities to evolve and transform in positive ways. The reverse is that if certain groups aren’t thriving, then that’s going to impact other people at some point down the road. Communities are not going to be sustainable, and we’re going to stagnate, not reaching our individual and community potential for growth.

So, while environmental justice initiatives help certain groups in very specific ways, broadly environmental justice helps sustainability and resilience for your whole community, your whole state, or the whole nation and eventually the world.

Everything is interconnected, and when you start to support those pieces and address social vulnerabilities that exist in our communities, you’re helping everyone, including yourself and your family.

What did you explore in Wilmington?

Essentially what I wanted to find out was how nonprofit organizations understood the disaster recovery experiences and needs of the Latina and Latino community. But also, how well they understood that community in general — and ultimately how that influenced their ability to serve it.

I was interested in the Latina and Latino community because I’m Puerto Rican, and it’s personally meaningful and interesting to me. But you could reframe this study for any other group. “Recognition,” which is what this study focused on, is acknowledgement, respect, legitimization, and, really, validation of group differences.

What I tried to do was use interviews to start to get an understanding of how well nonprofit leaders understood what the Latina and Latino community in Wilmington was like, and how often they engage with this community. And then I would transition into talking about the leaders’ organizations, their purposes and their missions, and then bring it back to how they addressed the needs of underserved groups.

Why is it important to focus on nonprofit organizations as sources of aid and assistance after disasters?

Nonprofits are critical resources for disaster recovery. They provide so many different types of services. Some are smaller in scope. Some are very large and provide a lot of support to communities. Some nonprofits are focused more on certain groups and advocacy for those groups. But I think that communities overall really rely on nonprofits in response and recovery.

Part of that is because a lot of these nonprofits are in the spaces. They’re on the scene. So, they know what’s happening because they’re experiencing it. They’re also physically accessible. They’re the first groups there.

They likely have been in that community prior to the disaster, too, which means that they have pre-established trust and communication networks in the community, which makes them more accessible to members of the community that disasters impact.

Given the position of nonprofits in the community, I think there’s a huge potential for them to make a very large positive impact for the Latina and Latino community if they aren’t already. My work tries to understand factors that can support that potential.

How well did the nonprofit leaders involved in disaster recovery in Wilmington understand the Latina and Latino community?

There was a big spectrum within which nonprofits recognized this community. Some just saw it as a group that spoke a different language. But, on the other hand, you also had people who were deeply aware of ethnic and cultural diversity within the Latina and Latino community, as well as the corresponding differences in the values and priorities and experiences and needs of those groups.

Some leaders also had knowledge of how these diverse groups were interacting with their local environment — and the impact that the environment and context had on those groups —as well as the different capacities and strengths of the Latina and Latino community.

Most nonprofit leaders probably fell in the middle of the spectrum of recognition, but there were some key individuals that were on that higher end.

How did leaders’ levels of recognition affect their nonprofits’ delivery of services?

When recognition of the Latina and Latino community was more substantial, organizations moved beyond what you see as standard practices, which typically might only include translation, for instance, in delivering information.

Instead, different modes of communication emerged, different strategies to get the messaging out. You saw more connected networks of people and organizations. You saw changes in resources that they provided or in approaches to distributing resources. You saw policy changes.

Those were things that we observed when nonprofit leaders possessed an increased recognition, or recognition of certain dimensions, of the Latina and Latino community. That was a key finding.

Are nonprofit leaders invested and engaged in promoting outcomes that are just — and, if so, what does that mean as we look ahead?

At the time I was speaking with nonprofit leaders, I think aspirational goals for a lot of them would include just outcomes and supporting environmental justice. I think that there were organizations with a focus on supporting certain groups, but they didn’t call it “environmental justice” or “just outcomes.”

I think if you were to sit down and consult with most nonprofit organizations about the ways they could promote environmental justice and support just outcomes, they wouldn’t be resistant. They would be excited and eager and willing.

Our study makes several practical recommendations, outlining a process for evaluating how planners and leaders can conduct internal assessments of their organizations and identify their gaps or their strengths. We also provide concrete recommendations about ways to support better recognition. We use examples from Wilmington to offer ideas about how recognition can ultimately translate into changes in procedure and how nonprofits distribute resources.

I think that it’s complex in that there are issues around funding and resources and time. One of the things I took away from the interviews was that nonprofit organizations can’t do everything. They can’t recognize all underserved groups to the degree that would be ideal, to the degree that always would support just outcomes for those groups. That’s not what’s feasible or practical.

But I also don’t think that should be an excuse for not doing things.

I spoke to one organization that knew very little about the Latina and Latino community, but we ended up talking about an entirely different underserved community. They had an amazing level of recognition and understanding of that group, to a degree that I think would be unlikely for any of the other organizations that I spoke to. So, my takeaway was that as an organization you need to understand what your strengths are, what your gaps are, and then you can address some of those gaps.

If it’s not feasible to address all gaps, you need to think about the other groups and people in that space.

I think that to really support nonprofit organizations, we need to expand our lens and think about it more broadly. How can organizations cross-pollinate? How can they learn from one another? How can they directly support one another? How can they leverage each other, and how can they function together as an ecosystem of nonprofits working in this space? And how can we support nonprofits in doing that?

MORE

Climate Risk Management published Olivia Vilá’s study, which she completed with the support of co-authors Bethany Cutts, Whitney Knollenberg, and Louie Rivers: go.ncsu.edu/recognition-study.

- Olivia Vilá on “The Winding Path of Research” from the Winter 2020 issue of Coastwatch

- “Resilience and Redevelopment in Duffyfield” from the Spring 2023 issue of Coastwatch

- “Bouncing Forward: New Resilience Programs for Coastal North Carolina” from the Summer 2023 issue of Coastwatch

- more from Coastwatch on resilience

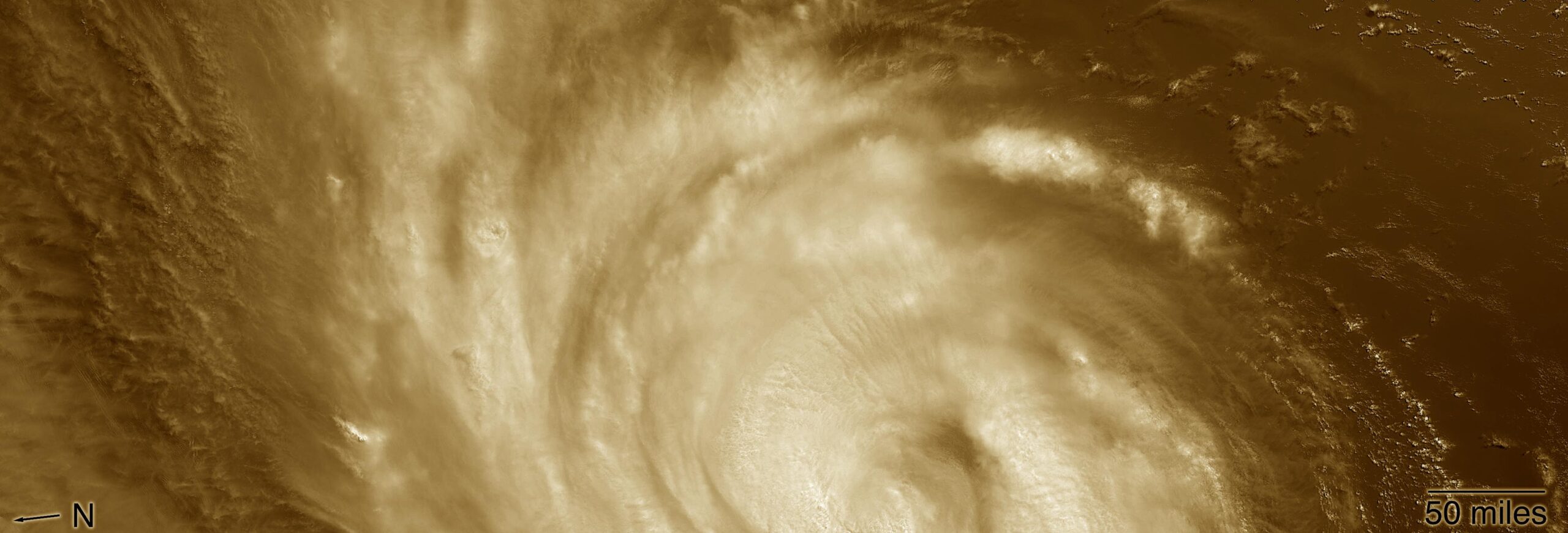

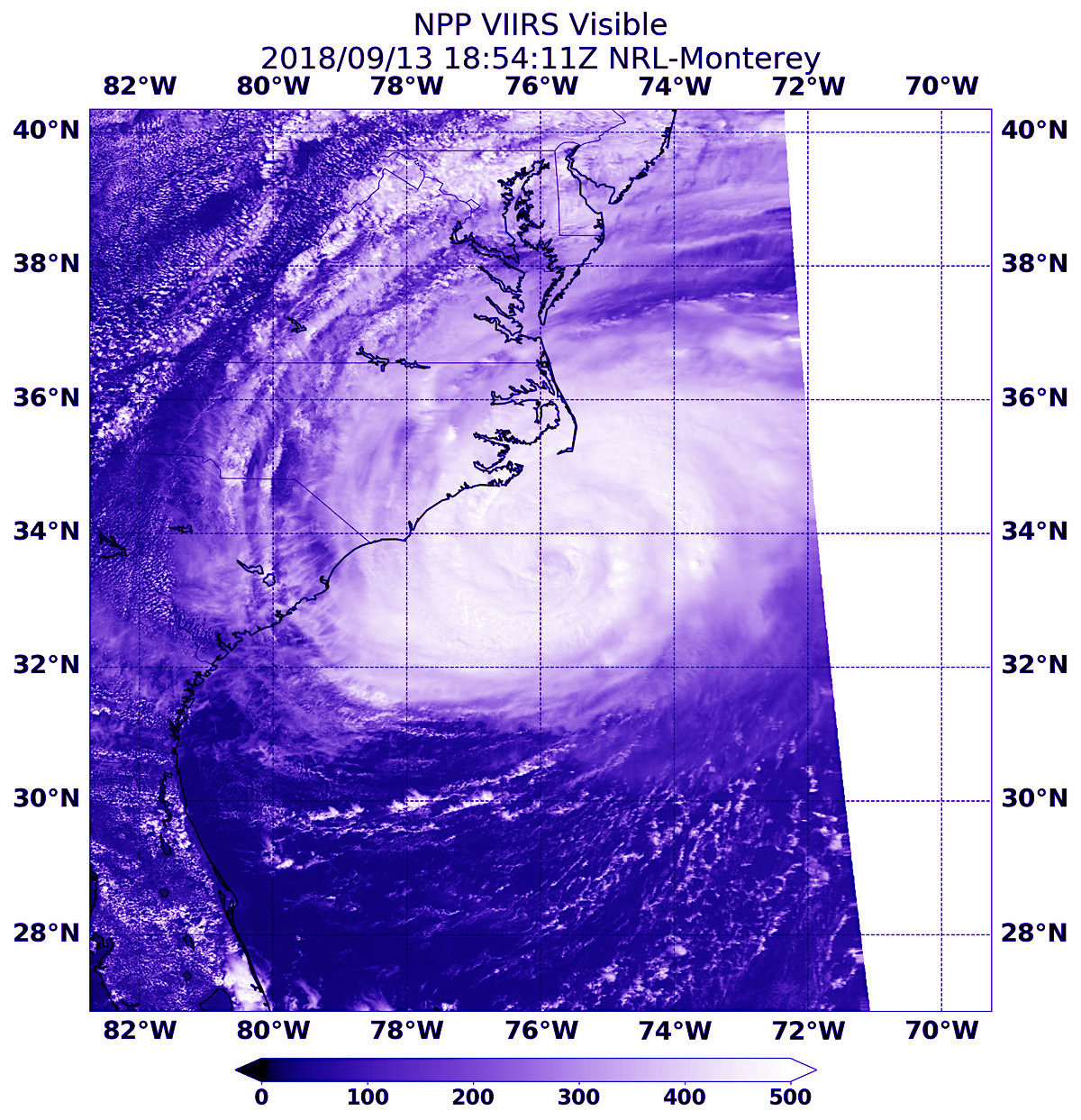

lead photo: Hurricane Florence. credit: NASA/GSFC/LaRC/JPL-Caltech, MISR Team.

- Categories: