Winding Path of Research: Flood Risk, Recognition, and the Latino and Latina Community in Wilmington, NC

When nobody showed up for her study, Olivia Vilá changed course — and her work shed new light on environmental justice.

Integrating principles of citizen science and environmental justice into decision-making and policy-making processes may help address water-related inequities. My own research focuses on disaster and natural hazards, but graduate students, as well as emerging researchers and scholars, can draw lessons from a range of disciplines and across research topics.

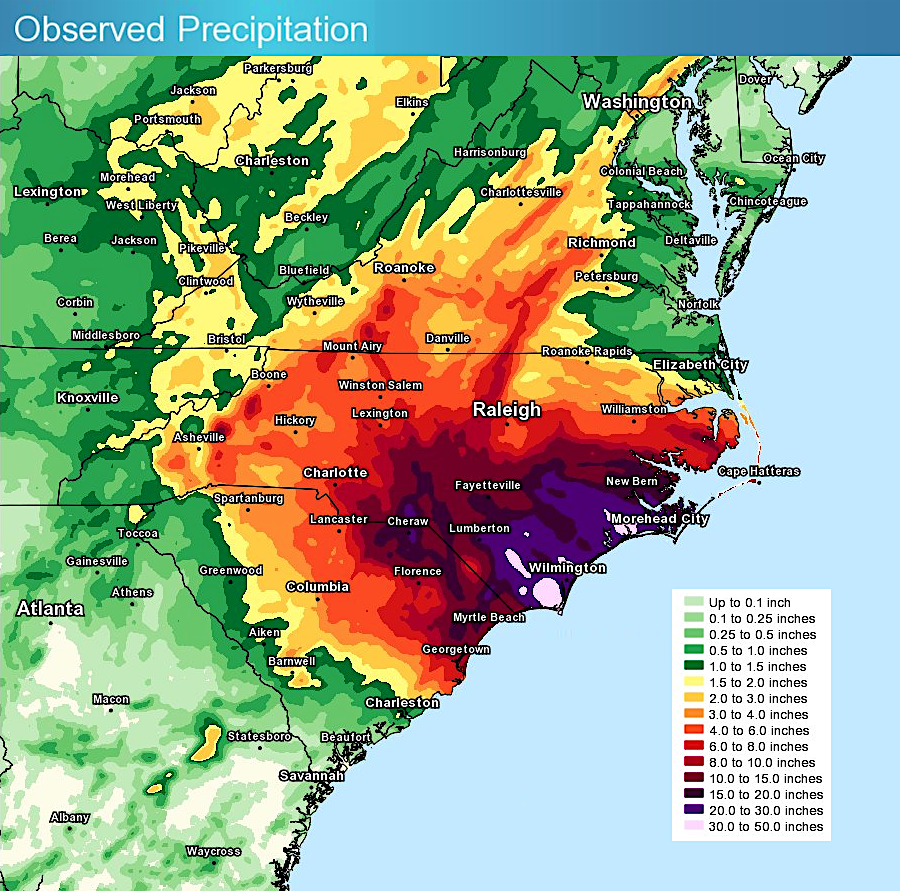

My original research proposed helping the Latino and Latina community map their flooding concerns and community assets. I thought doing so could create a more accurate representation of flood risk for this population. Before going into the field, I recognized I needed to work with collaborators in the community who already had established trust with the Latino and Latina community, especially because the schedule for my study did not allow enough time for me to genuinely build up trust in that community.

Because of this, I connected with El Centro Hispano at the University of North Carolina Wilmington. Together, the El Centro team and I discussed strategy, revised research materials, and coordinated bilingual volunteers who could help recruit and run the interactions with participants.

The results? My first day of data collection arrived and no one except for the research volunteers showed up.

I was devastated. My initial reactions were that I had selected a terrible venue for participants to meet and that I should have done more outreach and promotion.

Still, my gut was telling me something different: No matter what venue I picked or how much outreach I did, nobody would show up.

Take 2

For research to reflect the needs of a community, it must involve that community in the process. So, instead of sticking with my original plan, which I had developed in academic isolation, I decided to go back to the drawing board. This time, I devised a research plan in collaboration with the Latino and Latina community, integrating the community into the scientific process.

I spent the next several months immersing myself in the community and having conversations with stakeholders who knew it much better than I did. I also went to community meetings and got to know the socio-political landscape of the study area. Through this iterative and collaborative process, my research design evolved in a way that aligned with community needs and context, while still adhering to the broad goals I had set forth in my original research proposal.

This meant that my study shifted in a couple of meaningful ways.

First, my research population changed from the Latino and Latina community in Wilmington to the individuals and organizations who work with that community. As I had come to find out, there were deep issues of fear and distrust of outsiders — barriers that I couldn’t overcome within the timeframe of a short study cycle. In addition, by researching the individuals and organizations who worked with the Latino and Latina community in Wilmington, I actually was able to focus my research on better understanding issues associated with flood events and recovery for the population I wanted to target.

Second, instead of creating community-relevant maps of flood risk for geographically-identified areas of importance to the Latino and Latina community — where they live, work, and enjoy recreation — I’m creating network maps of the people and organizations who can support the Latino and Latina community to better prepare for, respond to, and recover from flooding events.

Although environmental justice work had inspired my original intention with maps, what I hadn’t considered was that the population I was hoping to help by mapping their spaces didn’t want to be mapped. In fact, the population I hoped to help feared interactions with government and political processes.

So, while the new research design was more feasible and more relevant, was it still useful for my study’s goals? Was my research completely sidetracked because my original plan didn’t work?

On the contrary, the results that began to emerge in the data unexpectedly illuminated the thread, the theoretical framework, that was going to help define my identity as a scholar.

What is Environmental Justice?

Historically, environmental injustices have been documented in terms of the disproportionate exposure to environmental risks and hazards that people of color and low-income populations face. However, some of the most recent discussions in environmental justice have begun to highlight how environmental injustice also is a matter of recognition, political representation, and participation.

For example, it is not enough simply to know if flooding impacts the Latino and Latina community. I must also ask if and how flooding disproportionately impacts the community. Do those in power understand who flooding disproportionately impacts? Do people in power respect the perspectives and experiences of people in the community who experience flooding? Do people who feel the impacts of flooding participate in decision-making?

The findings emerging in my study seem to be consistent with environmental justice research. Through my engagement with people and organizations involved in disaster response, recovery, and hazard mitigation, it became clear there are different levels of recognition of the Latino and Latina community in Wilmington. Additionally, leaderships appear to play an important role in facilitating that recognition. Those variations in recognition seem related to the extent to which the organization or local officials could, or would, effectively serve that community.

In other words, inequity in the distribution of resources and risks seems to be, at least in part, related to the awareness and understanding of marginalized populations.

As a disaster social scientist, the finding that recognition may be an important component for equitably serving marginalized communities is especially exciting, because recognition remains one of the least understood components of environmental justice.

The answers to the questions my study posed will not only be relevant for decision-making and policy-making associated with flooding, natural hazards, or disasters; such findings can inform any process that results in the distribution and allocation of risks and resources.

Looking Ahead

Community members and organizations who have collaborated on the project have been receptive to the research findings. To continue to build and nurture partnerships, I plan to work with stakeholders in the community as I analyze my results, and, based on my research, as we then develop products the community can use. I also hope to bring the work directly to the community.

I plan to present this research in summer 2021 at the annual Natural Hazards Workshop and Researchers Meeting in Boulder, Colorado, where I hope to share findings at one of the most diverse conferences I’ve ever attended.

When I started this study, I had misrecognized the study population I was trying to research, which ultimately led to research methods that were not effective. However, more culturally appropriate and relevant research methods ultimately yielded better and more practical research.

Olivia Vilá received a joint North Carolina Sea Grant – NC Water Resources Research Institute Graduate Research Fellowship and is a doctoral student at North Carolina State University.

North Carolina Sea Grant – NC Water Resources Research Institute Graduate Research Fellowship