From the Courthouse Steps to Climate Change: How Lumbee History Can Inform New Social and Environmental Dialogue

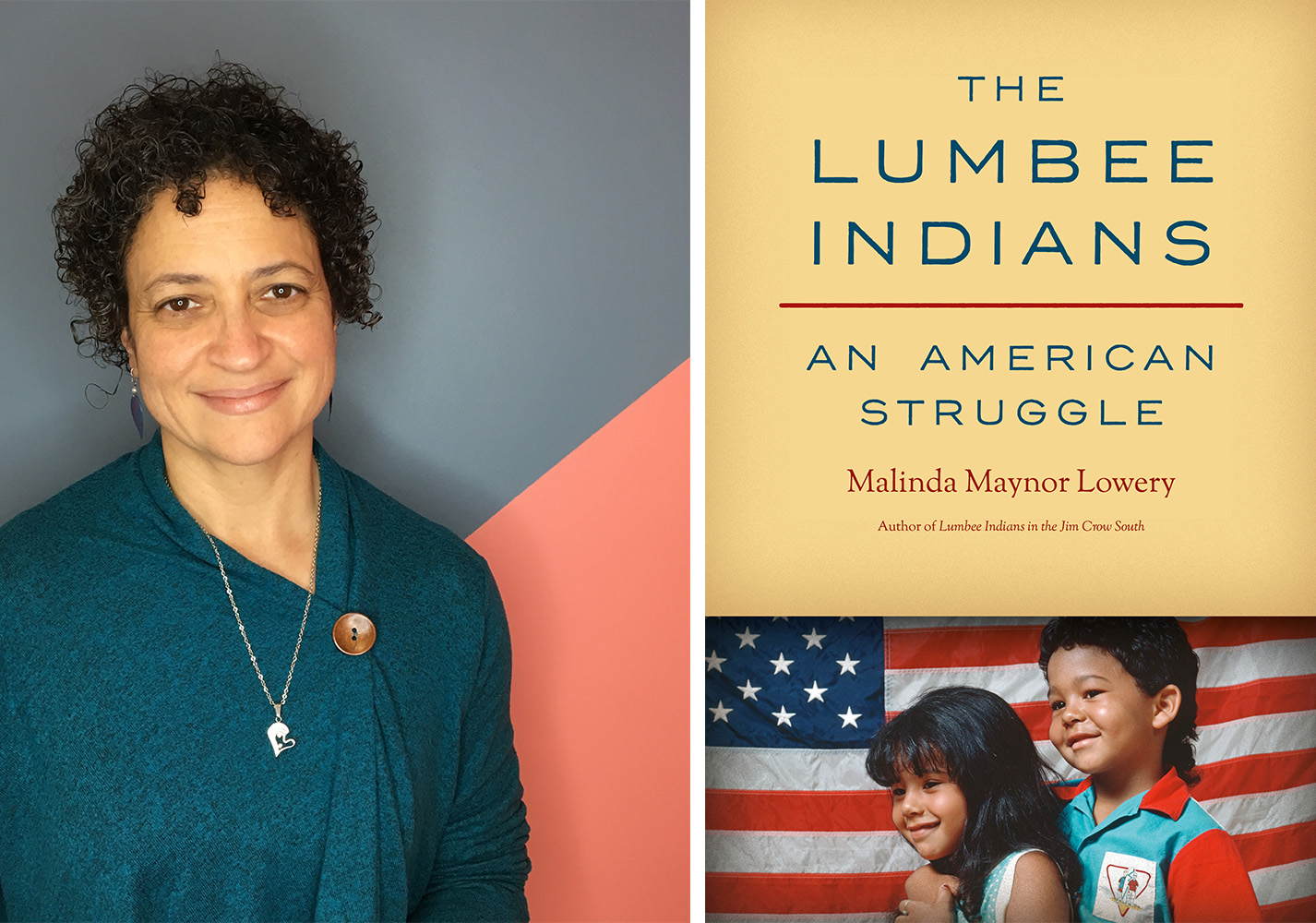

A Q&A with Malinda Maynor Lowery

The Lumbee tribe remains the largest east of the Mississippi and among the largest in the United States, living on its original homelands and maintaining a distinct identity and sense of community. Malinda Maynor Lowery’s The Lumbee Indians: An American Struggle weaves together the histories of indigenous peoples and Europeans in America. Lowery spoke to us about Lumbee history, what it means to be indigenous and American, and how the tribe’s struggle for justice and self-determination is relevant today. (Read the first chapter of the book here.)

Why did you write The Lumbee Indians: An American Struggle?

I really wanted to help people see how the Lumbees have created themselves as a nation that would mirror our understanding of how the U.S. has been created as a nation. I based the chapter Coastwatch excerpted on what I could know from the documentary record about the indigenous communities that coalesced to generate who the Lumbee people are today. George Lowry sprang forward as the only person we have on written record to tell a Lumbee origin story. In fact, his speech on the courthouse steps is also the one origin story from a Lumbee and not from somebody talking about us from the outside.

Why is George Lowry’s speech on the courthouse steps relevant today?

The relevance of that speech is still with us when we think about how native peoples are routinely silenced and erased. At the moment of the inquest about his murdered sons, George Lowry would not be silenced. And I think it’s powerful — he’s a beacon of understanding about what it means to not be silenced.

How does Lumbee history inform what happened in Robeson County after Hurricanes Matthew and Florence?

The accumulation of those two catastrophic events is a kind of metaphor in some ways for colonialism: one bad thing after another. Fundamentally, indigenous people remain indigenous because they survive with a sense of themselves, as a political community, intact.

It’s important for any policy response to fully incorporate input from the Lumbee community as political actors, not simply as “victim citizens.” The Lumbee people have quite a number of resources to solve problems. That’s our engagement with American identity: We’re problem solvers.

When folks try to address emergency response or infrastructure issues, they can take advantage of the perspective and expertise of Lumbee people by virtue of their long-standing attachment to the land and how they value it. I think with Florence and Matthew it’s pretty practical to ask: What do we know about the Lumber River? What do we know about how our land is situated there? What kind of ways do we have to rethink the hurricane as a phenomenon, because it’s not just a coastal phenomenon?

We also have Lumbee hydrologists, engineers, politicians, accountants — all sorts of people whose expertise we can harness to address these problems. When no one takes advantage of that expertise, we’re missing powerful resources to address crises.

Will storms like Matthew and Florence ever diminish the Lumbee capacity to remain a community?

I feared that Matthew and Florence would cause widespread displacement — and not just of Lumbees, of course, but of many poor people in Robeson County. But what I feared didn’t seem to come to pass to that degree. Whether you’re Lumbee or not, if you were born and raised in Robeson County and you’ve lived there for several generations, the universal feeling that I’ve gotten from people is no, we’re not going anywhere. We’re just going to rebuild and try again and hope for better from the decision- makers who allocate the resources.

How can a Lumbee perspective contribute to dialogue about climate change?

To those of us who aren’t scientists, climate change and its destructive consequences seem inevitable and unavoidable. Lumbee knowledge of place and attachment to place tell us that nothing is inevitable.

Do we ignore opportunities to make policy changes or infrastructure changes? Do we ignore opportunities to mitigate impact or eliminate impact? The broader Lumbee history informs these questions. It says the consequences we face are generated by the qualities of our relationships. We have stayed where we are, and we have maintained our relationships to this place because we value the nature of the relationships themselves, and because we are willing to sacrifice for those relationships to maintain them and keep them alive. That type of choice values history and can inform whatever decisions are made about the future of our planet.

Malinda Maynor Lowery, a member of the Lumbee Tribe of North Carolina, is a historian and the director of the Center for the Study of the American South at UNC-Chapel Hill.

To read the first chapter of The Lumbee Indians: An American Struggle, by Malinda Maynor Lowery, click here.

This article was published in the Spring 2019 issue of Coastwatch. For reprint requests, click here.

- Categories: