When an Indian emissary met the English ships in July 1584, things went so well that Wingina decided to try to adopt the strangers.

The Lumber River winds into and out of the heart of Lumbee land. Photo by Gary Dincher/CC BY-SA 2.0

By Malinda Maynor Lowery

Excerpted from “We Have Always Been a Free People: Encountering Europeans,” the first chapter in The Lumbee Indians: An American Struggle, by Malinda Maynor Lowery. Copyright © 2018 by Malinda Maynor Lowery. Used by permission of the University of North Carolina Press. www.uncpress.org

In the winter of 1865, the bleakest of his life, George Lowry stood on the steps of the Robeson County courthouse. He had just emerged from an inquest into the murders of his two sons. He was 67 years old, born following an American Revolution. The county coroner had identified the Confederate soldier responsible for his sons’ deaths at the inquest, but the killer remained at large. The sheriff refused to arrest him.

Consumed with the iniquity of these events, Lowry unchained a spontaneous, unrestrained history lesson, describing his people’s conception not in the sin of slavery but in the virtue of freedom: “We have always been the friends of white men. We were a free people long before the white men came to our land. Our tribe was always free. They lived in Roanoke in Virginia. When the English came to Roanoke, our tribe treated them kindly. One of our tribe went to England in an English ship and saw that great country.”1

In his story of his people’s origins, Lowry emphasized the Lumbees’ freedom, their hospitality and reciprocity with English newcomers, and the journey from their original homeland, Roanoke, where these virtues were nourished. Lowry sought to strike a blow against death by pointing out the betrayal of at least one of these virtues, friendship with whites.

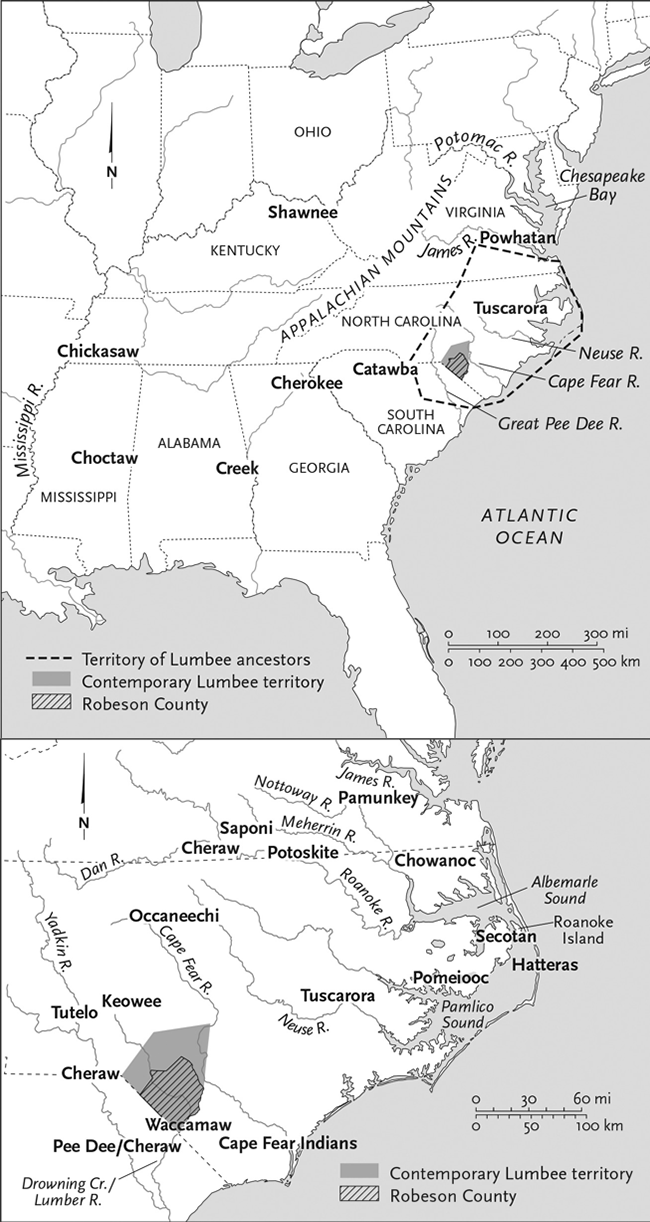

George Lowry’s view may not be the only version of Lumbee origins, but it nevertheless gives us a legitimate starting place from which to piece the documentary record together. That process begins with an understanding that the Lumbees’ homeland is larger than Robeson County. Many of the Lumbees’ ancestors came from places as far north as the James River in Virginia, south as the Santee River in South Carolina, east as the Atlantic Ocean, and west as the Great Pee Dee and Catawba rivers. That territory may not belong to them today, but it produced them nonetheless. “Roanoke” is neither the beginning nor the end of this tale of journeys, a tale that belongs to Indians in the southern United States in particular and to Americans generally.

Today we understand the word “race” to mean members of a group who share certain physical traits and a common culture, allowing for possible differences in customs and attitudes, as northerners are different from southerners in the United States. But before the settlers came, Indians in North and South Carolina and Virginia were enormously different from each other, physically and otherwise. Even so, they had much in common — all valued family, and many placed heavy emphasis on the power of women to determine belonging and make political decisions, including tracing a family’s descent from the mother’s line or from the lines of both parents equally, rather than only from the father’s.2

Many of the Lumbees’ ancestors came from places as far north as the James River in Virginia, south as the Santee River in South Carolina, east as the Atlantic Ocean, and west as the Great Pee Dee and Catawba rivers. Maps courtesy of UNC Press.

In the 1580s, when Sir Walter Raleigh’s soldiers and settlers ventured into North America, they landed at the place the Algonquian speakers called Roanoke, named after people who make things smooth or polish things, possibly referring to the shell beads that a select group of skilled artists produced. Despite their intentions to subdue land held by savages, the English found themselves having to play by the rules of this place, just as the Indians did.

Nothing was inevitable about the conquest that unfolded, and epidemic-inducing germs did not do all of the work. Violence, slavery, unchecked English immigration — all were the results of decisions to aggressively seize land owned by others. The earliest colonists were scientists, soldiers, diplomats, and pirates who had honed their skills in wars against the indigenous people of Ireland and against the Spanish Armada. Raleigh and his soldiers largely considered their efforts in North America to parallel their colonization of Ireland, and they believed that the Irish and the Indians in the Americas possessed the same savage qualities. But unlike with the Irish, Raleigh ordered his soldiers to treat the native inhabitants of this new world kindly, to learn everything they could about the people whose land the English wanted to claim.3

Roanoke Indians and the English found that they had a lot in common. When an Indian emissary met the English ships commanded by Arthur Barlowe in July 1584, things went so well that Wingina, a werowance (principal leader) of Roanoke and other villages, decided to try to adopt the strangers. They both loved to trade, and they each offered items that they believed the other would value. The English offered ornamental things: metal serving dishes, mirrors, and beads. Indians gave the sailors food, hosted dinner parties, showed the English how to bathe properly, and volunteered protection against their enemies.

Barlowe and his men did not ruffle the Indians of the Roanoke region. For centuries, the Indians had dealt with strangers in one of two ways: by making war on them or by making family of them. Waging war on the Raleigh expedition was unnecessary — none of Barlowe’s men had attacked them, and these new strangers did not appear to be a threat but simply seemed scared and weak. Further, Barlowe arrived at an opportune time. Wingina had been engaged in a bitter and deadly war with Indian enemies, the Pomeioocs, who lived on the Neuse River. A few years earlier, the Pomeioocs and their allies escalated the war by killing thirty Secotan warriors at a peace conference. Making the English enemies was unnecessary, but making them kin was desirable.4

Wingina was looking for new allies with unique montoac (power), and the English seemed like good candidates. Their ships were useless, but the cannons and guns were a form of montoac that could defeat the Pomeioocs. When Barlowe decided to leave, Wingina sent two of his allies back to England with him, men named Wanchese (of Roanoke) and Manteo (of Croatoan). Neither men were “chiefs,” as the story has been told; instead, Manteo’s mother was the principal leader of Croatoan, and Wanchese was a warrior from Roanoke. Wingina counted both men, and their villages, as kin. Their assignment was to cross over into English culture and bring back as much intelligence as possible about these strangers who might become useful allies.5

The two men stayed at Sir Walter Raleigh’s mansion in London, learning English and teaching Algonquian to a scientist named Thomas Hariot. In six months they had learned enough to interpret both languages. They created an orthography of their Algonquian language and translated it into English, a document that became the foundation of a written form of an American Indian language. The bottom of this document bore a phrase written in the signs of Algonquian: “King Manteo did this.” Undoubtedly Manteo and Wanchese saw savagery in English culture: filth, disease, and noise; men who hoarded wealth; women whose husbands completely controlled them. One woman defied that cultural norm in England: Queen Elizabeth. Manteo would have seen his own mother treated with the same deference that Raleigh gave Elizabeth.6

Manteo and Wanchese returned home in 1585, accompanied by a force of 600 Englishmen — half of them soldiers — and their weapons. This time, Raleigh was not just exploring; he was creating an “outpost of empire.” He intended to establish and fortify a site in Virginia to prevent the Spanish from gaining any ground there. He thought he had secured Wingina’s friendship and Manteo’s and Wanchese’s loyalty. He did not think to ask their permission.7

After they landed, the commander of the 1585 expedition, Ralph Lane, began to believe that Wingina was going to betray the English’s weak colony to Indians farther west. Lane’s men ambushed and destroyed Manteo’s village of Croatoan, killing Wingina and impaling his head on a stake. Then, in the midst of a hurricane (probably something that he had never experienced), Lane fled the Carolina coast with the pirate Sir Francis Drake, who picked him up after pillaging Spanish settlements in Florida.

Drake had captured several hundred Africans and Indians in his raids, and it is possible he left them on the Outer Banks when he picked up Lane’s men. One scholar calls these people the “first and almost entirely forgotten ‘Lost Colony.’”8 A few weeks later, another small group of soldiers landed as reinforcements; they did not get the message that Lane had fled in despair. Wanchese destroyed that group in short order, not only exercising political vengeance but enhancing his own montoac; he showed his allies and his enemies that he was more powerful than Wingina and could do what Wingina would not.

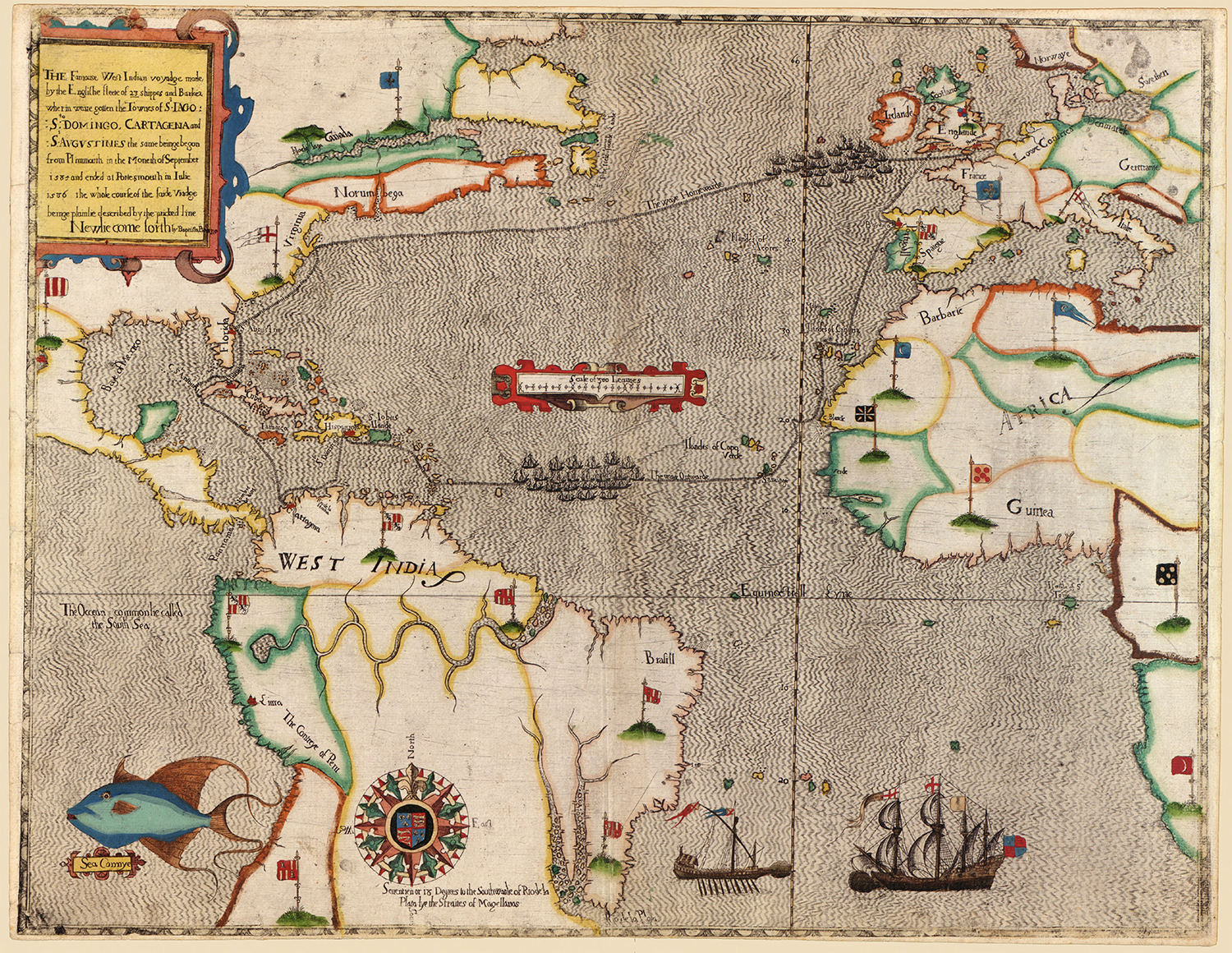

The commander of the 1585 expedition, Ralph Lane, fled the Carolina coast with the pirate Sir Francis Drake, who picked him up after pillaging Spanish settlements in Florida, part of Drake’s 1585-1586 transatlantic travels. Map from the Library of Congress.

In the meantime, Manteo seemed to secure his kinship ties with the English: He was increasingly fluent in the language, and he wore English clothes (at least when the English record keepers saw him). Lane’s men did not kill him in the massacre at Croatoan, and he boarded Drake’s ship with Lane and left for England. Whether he escaped in despair at the massacre of his kinfolk or left intending to continue his diplomatic mission, we do not know.9

But he did come back home. Two years later, in July 1587, Manteo returned, this time with a mixed crew, not just of explorers but of women, children, and farmers, all led by Governor John White. White was an artist, not a soldier. He knew of Lane’s expedition and wanted to repair relations; he needed Manteo to do so. When Croatoan warriors saw White’s English ship approach, they readied their arrows, having no reason to think that this bunch wanted to do anything but kill them, as Lane had done. Indeed, although White said he sailed to Croatoan with Manteo seeking to renew friendships, he still ordered his soldiers to disembark with their guns drawn. The warriors began to retreat at the shoreline, but Manteo called out to them. They stopped and greeted Manteo and the English, cooked them a meal, and proceeded to talk about what it would take for the two groups to be friends again. If White was as intelligent an observer as Manteo, he would have recognized that calling on the ties of kinship and alliance advanced him toward his goal.10

But White was still ambivalent; when the Croatoan werowance asked for a gift to seal their friendship, White refused, saying that English fury fell only on those who offended them and that English friends need not worry. Perhaps White did not know that Ralph Lane had killed innocent people, people who had thought of the English as friends. Indeed, White ended that day’s talks assuring the Croatoan werowance that the English would receive Indians again in friendship and forget all wrongs. White had gotten it backwards: Manteo’s people had been wronged, not the English. To no one’s surprise, except perhaps White’s, no Indian leaders came to “receive” English “friendship.”11

White waited seven days and then set himself on a course surprisingly similar to Lane’s. He decided to attack Wanchese, who had massacred the English soldiers who had arrived immediately after Lane left. On the morning of the attack, Manteo went with White’s soldiers. His reasons remain obscure; White says he was a guide, implying that he endorsed the English mission and wanted to help and that his alliance had been transferred to the English. I imagine Manteo had his own goals: Killing Wanchese would show Indian leaders, including their enemies inland, that Manteo had English power at his disposal. But in return, Manteo had to accept the demon consequences of English power, a lesson he learned that very day.12

Instead of killing Wanchese and his men, White and Manteo mistakenly attacked Croatoan villagers. These were Manteo’s own people, and they had posed no threat. After the smoke cleared, the English took all the food at the settlement and some of the survivors, including the wife and child of Croatoan’s werowance. A few days later, the English conferred a title upon Manteo, “Lord of Roanoke,” in exchange for his “faithful service,” and they baptized Manteo in the waters off of Roanoke. Perhaps he believed that allying himself with the power of the English God would assuage his anguish, that he could be forgiven. Perhaps he believed that the English God could protect him from the kind of vengeance that Wanchese had exercised on the Englishmen who paid for Lane’s sins. In any case, White did not turn on him, as Lane had turned on Wingina.13

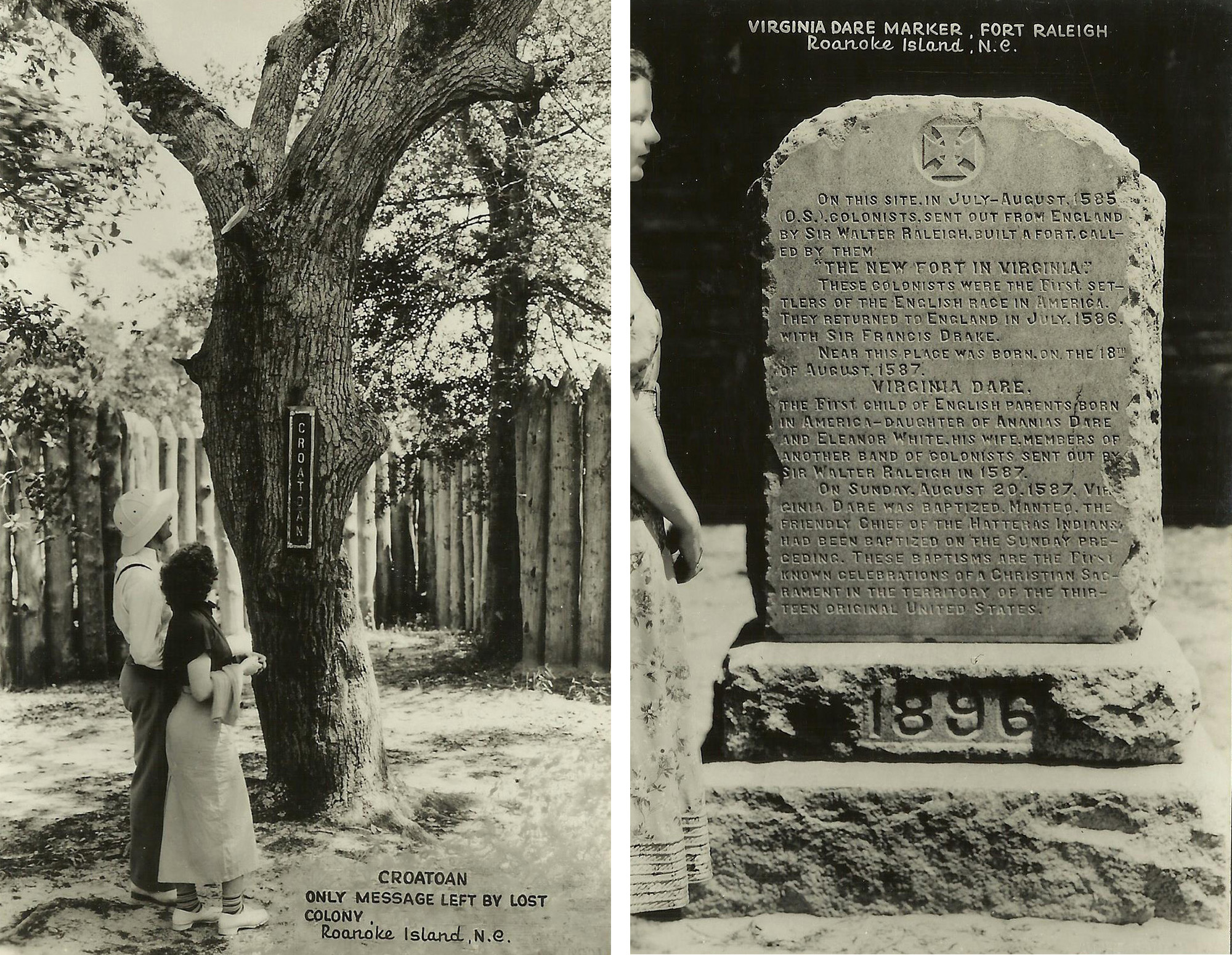

Left: Governor John White returned from England three years after Virginia Dare’s birth and found “Croatoan” carved on a tree, signaling that the settlers had taken refuge with White’s enemies — people he had brutally attacked. Photo courtesy of the State Archives of North Carolina. Right: The Virginia Dare Monument commemorates Dare’s birth and baptism in 1587. Photo courtesy of the Massengail Postcard Collection.

The English could have negotiated permission instead of courting animosity, but the arrogance of Ralph Lane and the ignorance of John White precluded common sense. Innocent people suffered as a result, both English and Indian. Five days after Manteo’s baptism, John White’s daughter, Eleanor Dare, gave birth to a girl and gave her the English name for her new home, Virginia. Her parents could hardly have imagined worse circumstances for their little girl. Under the haze of cultural superiority, the leaders of this expedition had alienated the only people who could help the settlers survive. Undoubtedly frightened at the prospect of how the Indians would respond to the killings, the English families demanded that White return to England to get more supplies. White, it seemed, had permanently damaged any prospect of friendship with the Indians, except possibly Manteo. Hoping it would be a short trip, he agreed.

White did not return until almost three years to the day after Virginia Dare’s birth. Unlike the previous ventures, when Indians had welcomed the English, no one came to the shore this time. White found the word “Croatoan” carved on a tree, signaling that the settlers had taken refuge with White’s enemies, people he had brutally attacked. By that time, Virginia Dare likely spoke Algonquian; perhaps her grandchildren never knew that she had been English. Her parents and their fellow colonists may have repeated the mistakes that led to Lane’s and White’s departures — explorer John Smith reported that Chief Powhatan, Pocahontas’s father, had killed them. However, the Indians of Roanoke, Croatoan, Secotan, and other villages had no reason to make enemies of the colonists; instead, they probably made them kin.14

The colonists did not disappear any more than Manteo’s Croatoan people had vanished. The man who recorded George Lowry’s history lesson on the steps of the Robeson County courthouse, Hamilton McMillan, believed that Indians from Croatoan adopted the desperate English settlers and that their descendants settled on Drowning Creek, later called the Lumber River. McMillan pointed to English surnames in the list of colonists (“Lowry” was not among them) and found parallel names among Robeson County Indians. While some of the surnames, such as Sampson, Brooks, and Berry, are unquestionable matches, most of the similar names are found as much in the English population as in the Lumbee population.

Further, we have no evidence that American Indians regarded English surnames as more special than any other kind of name; it is difficult to imagine that a group of Indians who took in foreign refugees would have changed their naming practices to accommodate these newcomers and then maintained them for over 200 years.15

McMillan also cited the writings of North Carolina’s surveyor general, John Lawson, who visited the island of Croatoan 12 decades after the English left Roanoke and found people there who called themselves Hatteras Indians. To Lawson, they appeared to possess English ancestry; some of them had gray eyes, and they told him how several of their ancestors “were white people” and “talked in a book.” Lawson did not record English names among the Hatteras, nor did he say that their culture possessed English characteristics.16

The Lumbee story is about what it means to be indigenous and American. Here, three Lumbee girls sing at a U.S. Army event honoring the tribe for its contributions to the nation. Photo by Timothy L. Hale/U.S. Army.

If the Hatteras Indians were not “pure- blooded” Indians, Lawson never discussed it, but such a category never would have occurred to him. At the time, the purpose of English colonization was to acquire Indian land; the mix of European with Indian culture was not significant to Lawson — the use and ownership of places was.

Hundreds of articles, books, plays, poems, a National Park, and a tourist economy in the town of Manteo, North Carolina, have been devoted to the story of these few dozen “lost” English colonists. Stephen B. Weeks, a respected North Carolina historian, called their fate “the tragedy of American colonization.”17 Weeks wrote that if McMillan’s theory of Lumbee origins is rejected, “then the critic must explain in some other way the origin of a people which, after the lapse of 300 years, show the characteristics, speak the language, and possess the family names of the second English colony planted in the western world.”18

But there are many more plausible reasons for Lumbees’ similarity to Europeans other than their possible connection to the Lost Colony. First among them is that Indian people — like any others — change, borrow, and transform what they find useful, including languages, stories, food, materials, and religions. Far less is written in tribute to this process or to the Indians who continued to maintain power in that region for more than a century after these events unfolded. Of course, Indian people remembered, but their stories went largely unrecorded until Hamilton McMillan wrote down George Lowry’s eulogy for his murdered sons.

Almost 300 years after the English colony disappeared, George Lowry spoke of these events that prompted change, with the very specific intention of shaming the newcomers whom his ancestors had befriended but who had betrayed Indian people. That winter day, Lowry continued his origin story on the steps of the Robeson County courthouse: “When English people landed in Roanoke we were friendly, for our tribe was always friendly to white men. We took the English to live with us. There is the white man’s blood in these veins as well as that of the Indian. In order to be great like the English, we took the white man’s language and religion, for our people were told they would prosper if they would take white men’s laws.”19

Lowry, in his grief, glossed over the decisions that Indian people had made that led to English-Indian alliances. He emphasized how the Lumbees’ ancestors changed, borrowing English worldviews (through language and religion) that suited Indians’ determination to survive. But cultural change was a two-way process; both sides had to adapt. He knew he could not do justice to the whole story, not on that day when he wanted to expose the injustice of his people’s circumstances.

For an interview with author Malinda Maynor Lowery, click here.

For an interview with author Malinda Maynor Lowery, click here.

This article was published in the Spring 2019 issue of Coastwatch. For reprint requests, click here.

Notes

1 Hamilton McMillan, Sir Walter Raleigh’s Lost Colony: An Historical Sketch of the Attempts of Sir Walter Raleigh to Establish a Colony in Virginia, with the Traditions of an Indian Tribe in North Carolina. Indicating the Fate of the Colony of Englishmen Left on Roanoke Island in 1587, in O. M. McPherson, Report on Condition and Tribal Rights of the Indians of Robeson and Adjoining Counties of North Carolina, 63rd Cong., 3rd sess. (5 January 1915), S. Doc. 677, 50 (hereafter cited as McPherson Report).

2 The best resource to understand the diversity of Indigenous groups in the southeastern United States is Raymond Fogelson, ed., Southeast, vol. 14 of Handbook of North American Indians, series ed. William Sturtevant (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution, 2004); within that volume see Jason Baird Jackson and Raymond D. Fogelson, “Introduction,” 1–13; Blair A. Rudes, Thomas J. Blumer, and J. Alan May, “Catawba and Neighboring Groups,” 301–18; and Raymond J. Demallie, “Tutelo and Neighboring Groups, 286–300.”

3 Michael Oberg, The Head in Edward Nugent’s Hand: Roanoke’s Forgotten Indians (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2008), 37; Colin G. Calloway, White People, Indians, and Highlanders: Tribal Peoples and Colonial Encounters in Scotland and America (New York: Oxford University Press, 2008), 34.

4 Oberg, 12, 32.

5 Oberg, 50–51.

6 Coll Thrush, Indigenous London: Native Travelers at the Heart of Empire (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 2016), 35–36; Oberg, Head in Edward Nugent’s Hand, 59–64; see also David Beers Quinn, Set Fair for Roanoke: Voyages and Colonies, 1584–1606 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1985), 39–40.

7 Oberg, Head in Edward Nugent’s Hand, 57.

8 Oberg, 102.

9 Oberg, 98–100, 101–2, 107–10; see also Thrush, Indigenous

London, 59.

10 Oberg, Head in Edward Nugent’s Hand, 112–13, 116–17.

11 Oberg, 118.

12 Oberg, 119–20.

13 Oberg, 120–22.

14 Oberg, 123–26; for a summary of theories on the Lost Colony’s fate, see Helen Rountree, Pocahontas’s People: The Powhatan Indians of Virginia through Four Centuries (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1990), 21–24.

15 Hamilton McMillan, Sir Walter Raleigh’s Lost Colony, in

McPherson Report, 51–55.

16 Lawson, New Voyage to Carolina, 62.

17 Stephen B. Weeks, “The Lost Colony of Roanoke: Its Fate and Survival,” reprinted from Papers of the American Historical Association, vol. 5 (New York: Knickerbocker

Press, 1891), 22, https://digital.lib.ecu.edu/13444.

18 Weeks, 39.

19 Hamilton McMillan, Sir Walter Raleigh’s Lost Colony, in McPherson Report, 50.